Tara Nolan

Source link

Home & Garden | ReportWire publishes the latest breaking U.S. and world news, trending topics and developing stories from around globe.

Tara Nolan

Source link

The winter doldrums are a reality in the Midwest, especially for gardeners, but an immersive plant adventure at your local conservatory is a sure way to lift your spirits. Fortunately, midwestern cities and towns are blessed with many gardens under glass where visitors can experience the warmth and color of the growing season any time of the year. For me, an annual winter trip to the Garfield Park Conservatory in Chicago, just a two-hour drive from my home in southern Wisconsin, is the perfect way to get my plant fix and keep my sanity.

While I’ve been to dozens of conservatories throughout the United States and abroad, Garfield Park Conservatory continues to be a favorite. With its mission “to change lives through the power of nature,” this conservatory ticks all the boxes as a welcome winter destination, and the surrounding landscape is exceptional in every season.

Nestled within the 184-acre Garfield Park on Chicago’s West Side, Garfield Park Conservatory has two acres of naturalized landscape gardens under glass and 10 acres of outdoor spaces that include a sensory garden, a demonstration garden, and a play-and-grow garden for kids.

The conservatory, which opened in 1908, was designed by the famous landscape architect Jens Jensen to be the world’s largest conservatory under one roof. Still one of the grandest glass houses in the world, it has persisted through trials, tribulations, and weather damage over the years, with the most recent restoration in 1994. Funded by the Park District of Chicago and the Garfield Park Conservatory Alliance, the conservatory’s mission is to exhibit “landscape art under glass.” Admission is free.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Garfield Park Conservatory features eight indoor show houses and is open to the public throughout the year. The Palm House is the largest room at 65 feet tall and 90 feet wide, but the Fern House and the Desert House are my favorites. Over 250,000 annual visitors, including many schoolchildren, enjoy the conservatory and its surrounding gardens.

The conservatory typically presents five dynamic flower exhibits per year, as well as extensive education opportunities, events, programs, cultural performances, and demonstrations. Check out the website, garfieldconservatory.org, for directions, hours, and more information on this amazing destination. Reservations are encouraged in advance of arrival. I’ll be making my next trip soon, and I hope you will also seek out conservatories in your area this winter. It’s worth it!

Mark Dwyer is the garden manager for the Edgerton Hospital Healing Garden in Edgerton, Wisconsin, and he operates Landscape Prescriptions by MD.

Photos: Mark Dwyer

For more Midwest regional reports, click here.

In the mood for some virtual garden travel?

Mark Dwyer

Source link

From cherry blossoms in December to spring bulbs in January, I’ve seen some flowers bloom exceptionally early. If you’ve also seen some early blooms, you might be worried about how this will affect your plant when it inevitably gets cold again. Here’s what you need to know about early blooming flowers.

It’s been a weird winter here in Vancouver. For a while, we had a very, very, cold snap. Then quickly, it warmed up and turned bright and sunny…only to get cold again.

I saw cherry blossoms in December—which doesn’t usually happen until late February.

I’m confused. The plants are confused. We’re all confused.

All across the world, we have been seeing extremes. So it’s no wonder I’ve been seeing lots of questions from gardeners about what will happen to their plants if they see early blooms.

If you’re concerned about early blooming flowers, join me as we look at the plant’s life cycle and what will happen to your plants should they sprout a wee bit early.

It’s getting harder and harder for some (I won’t name names) to deny that the climate is changing. We will see very unusual things happening with the weather, and the plants will respond to it.

Some areas are seeing more prolonged periods of drought, while others have heavy rainfall. We may have a cold, severe winter, but they’re getting less frequent as these mild winters creep up on us.

Because of these temperatures, we’re seeing longer growing periods with an earlier last frost date and a later first frost date. In the US, the growing season has increased by more than two weeks compared to the beginning of the 20th century in 48 states. In the UK, flowers bloom an average of 26 days earlier than in the 1980s.

The plants are getting the message loud and clear. They’re responding to the climate the best way they know how, one of which is early blooms.

As the climate changes, the plants are also changing. Anything that’s a perennial, like trees, shrubs, perennials, and bulbs, will continue to evolve. The strongest plants will be the ones to survive this.

The next generation of plants will create their future. The plants will become hardier in these conditions as the climate changes. The weaker ones may not make it, but the stronger ones do.

It’s always important to consider the plant’s life cycle, like what we do in pruning. Most plants go dormant in the winter by dropping leaves, stopping flowering, and devoting their energy to the root system.

That goes for most plants, like perennials, trees, bulbs, and even our edible vegetable plants.

When shoots come up early, remember that very little of the overall plant energy is above the soil line.

If it cools down again and there’s damage to the plant, most of it is still safe under the soil. There may be some damage to the above plant material, but the rest should be fine.

There may be some gnarly leaves and fewer flowers. She may not be looking her best. But know that she’s looking beautiful beneath the soil and will survive just fine.

Place your trust in the plants. Observe, but try not to worry. You can’t do much—it’s in the plant’s hands!

Perennials can pop up early when they see the cues of spring. But once it freezes again, the plant’s energy will retreat to the root system.

The plant isn’t fully developed above the soil, but it can still withstand some damage to the upper part of the plant. It’s rare that any of that damage will go down to the root.

Soil is very insulating and will help maintain a temperature the plant is hardy to. If you planted it in the right space, that is.

Generally, the leaf buds will be okay on trees. Trees send out many leaf buds early in the season when it’s cold. If they lose some, the tree will be okay.

Flower buds, however, tend not to bounce back as easily.

This year, we had cherry blossoms blooming exceptionally early in Vancouver due to a mild winter. I anticipate that they aren’t going to flower as prolifically this spring. Since they tried to flower early, they likely won’t set out a second flowering.

Bulbs are very used to this seesaw of warm and cold temperatures. Bulbs store all their energy under the soil. Within the bulb, there is enough energy for the plants to grow before there’s much spring sun.

The shoots will begin to pop up when it feels right. Generally, most bulbs don’t mind the cold. Some, like snowdrops and crocuses, even thrive in the snow. Bulbs have very strong root systems that help them bounce back in cold conditions.

The shoots may die off when it gets cooler again. But that’s fine. In the end, you could end up with fewer bulbs that are less robust and not as strong. This is more likely if there is a late freeze and most of the plant has already sprung up.

Some vegetables don’t mind cool temperatures. Imagine you didn’t cover your Swiss chard or kale, and it froze so much that it wilted and died back instead of getting sweeter (which we all hope will happen).

Those vegetables tend to grow back again. They might not grow back as much as before, but anything under the soil will be okay.

So your root vegetables, like parsnips, beets, or carrots, will be doing great underneath the soil, even if the cold damages the leaves above the soil.

We plant garlic in the fall (I always do so around Halloween). Sometimes, you can plant it a little too early or have a warmer-than-usual fall, and the garlic will send up shoots in the fall.

When it freezes, the garlic will die back. But don’t worry; the garlic will start the whole process again in the spring.

You can even plant garlic with shoots growing on it, like when you buy them a little late. This won’t affect your garlic overall.

Yes, there is a gold standard when it comes to garlic. Garlic growers won’t want shoots affected by the freeze or provide any stress to the plant as that can affect the overall robustness of the plant.

But will you still get garlic? Absolutely.

Let’s say it’s late spring and starting to get to summer, and we suddenly have an unexpected freeze. In this case, the plant’s chance of survival would drop.

At this point, most of the energy the plant is expelling is now on the upper part of the plant and not beneath the soil where it is protected.

Most perennials will bounce back, but the damage may be more significant if they are further down in their seasonal growth.

Rising temperatures and earlier springs will mean that bees will wake up earlier. It’s estimated that they wake up five days earlier than twenty years ago.

With more species blooming at the same time than in the past, there isn’t such a continuous, even supply of flowers for the bees. This mismatch between when the flowers and bees are active could threaten the bees looking for food sources.

This will also reduce plant pollination and their ability to reproduce and yield crops. Rising temperatures may also mean the bees come out earlier, but they need their timing to align with the flowers to avoid being affected.

Each plant (or seed or bulb) will respond to different environmental factors, such as temperature, amount of sunlight, light quality, and more.

As these conditions change, chemical production inside the plant triggers the growth. In response, the plant will begin to sprout new growth.

Many plants start growing when temperatures get warmer or the days get longer. Each plant will have specific responses, some needing higher temperatures or more light before growing. Others require less.

Likewise, cooler temperatures can tell the plant to redirect the energy back to the roots, set seed, and die back for the fall.

Stephanie Rose

Source link

We often erect a mental wall between planting an orchard and planting a vegetable garden. Either you have neat rows of trees, or you have neat rows of vegetables.

Here’s an orchard:

And here is a vegetable garden:

The former is a long-term investment that takes years to pay off. The latter is a quick return with more fertilizing, weeding, and daily effort.

Of course, if you’re a bit more free-spirited, you might go for a food forest instead, with various trees and perennial vegetables together.

However, let’s go back to the common vegetable garden/orchard divide. Getting fruit in an orchard may take 3-6 years, but then you get yields that can last for generations. Vegetable gardens provide quick and abundant harvests, yet you have to plant again every year.

Yet you don’t have to choose between having an orchard or growing a garden. And if you grow both, you don’t have to plant them separately.

You can combine them, particularly in the early years of an orchard.

Thus far, we’ve had good luck incorporating orchards and vegetable gardens together, getting the quick yield of annuals with the long-term yields of trees.

In our Grocery Row Gardens last year, we managed to grow 163lbs of cucumbers, over 150lbs of sweet potatoes, 760lbs of watermelons, 18lbs of Jerusalem artichokes, 10lbs of okra and about 40lbs of potatoes in between our fruit trees.

The vining crops acted like ground covers through growing season, with cucumbers dominating in spring, then being surpassed by watermelons, and then finally the watermelons being supplanted by sweet potatoes into the fall.

Our trees gave us nothing in yields as this was our first year; however, we still got over 1,000lbs of food from the system!

If you have an orchard, why not plant fast-growing crops between your trees? This works especially well in young orchards where the trees haven’t blocked much of the light yet. By the time your trees get big and start producing bushels of fruit and nuts, you will have already harvested tons of food from the space. Think pumpkins, sweet potatoes, watermelons and other ramblers, which you can start on hills and let run. Or get more intense and plant potatoes, corn, or other crops in beds between the trees.

Just something to think about. Our little backyard orchard/vegetable Grocery Row Garden system is outlined in this handy little booklet.

Even if you don’t plant a Grocery Row Garden, you can really up your game by adding some annuals to your orchard or food forest, particularly in the early years of establishment.

Welcome to a compilation of hilarious rock puns that’s sure to rock your world!

Whether you’re a seasoned geologist or simply someone who loves a good chuckle, these rock jokes are bound to deliver a good laugh. Get ready to rock and roll with these puns, quips, and geological gags.

1. What do you call a rock that never goes to school? A skipping stone.

2. Why did the rock become a musician? Because it wanted to be a little boulder.

3. Why are rocks so cheap? Because they’re always on shale.

4. What do you call a dubious rock? A sham rock.

5. Why do tectonic plates always argue? Because there’s too much friction between them.

6. What did the stone want to be when it grew up? A rock star.

7. Why did the miner stop digging? He was stuck between a rock and a hard place.

8. Why did the rock take confidence lessons? To help it feel boulder.

9. Why did the rock and the stone break up? The trust in their relationship eroded.

10. Why didn’t the stone get back together with the rock? He had too many faults.

11. Why did the rock shower every morning? It wanted to start with a clean slate.

12. It takes a boulder person to read through this list of rock puns.

13. Where do you take an injured rock? To the Rocktor.

14. What happened to the rock after continuous hours of interrogation? It finally cracked.

15. Where do wealthy rocks live? Rockefeller Street.

16. What kind of rocks are sour? Limestone.

17. Why was the gemstone scared for his exams? Because he thought he wasn’t going topaz.

18. How did the rock feel when he got covered in algae? He was lichen it.

19. What did the rock order at the bar? Soda on the rocks.

20. What did one volcano say to the other volcano? “I lava you so much.”

21. Where do rocks like to sleep? In bedrocks.

22. How did the stone feel after his workout? Rock solid.

23. How did the rock feel about going to jail? Petrified.

24. Why can’t minerals ever lie? Because they’re always in their pure form.

25. What did the rock say to the word processor? “Boulder.”

26. What did Sherlock Holmes say when Watson asked what kind of rock he was holding? “Sedimentary, my dear Watson.”

27. When were rock jokes the funniest? During the stone age.

28. What did the rock say when it ended up at the bottom of the hill? “That’s how I roll.”

29. Why did the rock go to jail? The quartz found him guilty.

30. What did the sedimentary rock say to the metamorphic rock? “You’ve changed, man!”

31. Why is it hard to be a diamond? Too much pressure.

32. Why did the rock decide to hit the gym? Because he wanted to be bigger and boulder.

33. Why was the rock emotionless? Because it had a heart of stone.

34. What do you call a rock that complains? A whine-stone.

35. Why are limestones ignored? Because they’re too chalkative.

36. Knock, knock. Who’s there? Geode. Geode who? Geode bless you!

37. Knock, knock. Who’s there? Shale. Shale who? Shale, we dance?

38. Knock, knock. Who’s there? Gneiss. Gneiss who? Gneiss to meet you!

39. How do geologists like their whiskey? On the rocks.

40. Why did the geologist quit his job? Because he wanted a clean slate.

41. What did the rock say to the geologist? “Don’t take me for granite.”

42. Why did the geologist keep their old rock collection? Because it had a lot of sedimental value.

43. What did Darth Vader tell the geologist? “May the quartz be with you.”

44. What’s a geologist’s favourite fruit? Pome-granite. (more fruit jokes here)

45. What’s a geologist’s favourite type of music? Rock & Roll.

46. What’s a geologist’s favourite band? The Rolling Stones.

47. What’s a geologist’s favourite restaurant? The Hard Rock Café.

48. What’s a geologist’s favourite sweet treat? Rock candy.

49. What’s a geologist’s favourite movie? Pyrites of the Caribbean.

50. What’s a geologist’s favourite kind of magazine? Rolling Stone.

51. Who’s a geologist’s favourite comedian? Chris Rock.

52. Who’s a geologist’s favourite actor? Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson.

53. What happens when you keep reading geologist jokes in your free time? You know that you’ve really hit rock bottom.

54. Why should you never expect perfection from geologists? Because they all have their faults.

55. Why are geologists so good in school? Because they don’t take anything for granite.

56. How do geologists like to relax? In rocking chairs.

57. Why don’t geologists argue? They’re too pelite.

58. Where do geologists study? At sedimentary school.

59. Why are geologists good at romance? Because they’re very sedimental.

60. Why don’t geologists like alcohol? Because they like to be stone-cold sober.

61. Why are geologists never hungry? Because they lost their apatite.

62. How does a geologist show their displeasure? They give the coal shoulder.

63. Why was the geologist tired of his work? Because it was mostly boring.

64. What happened after the geologist finished his work? It was a lode off his shoulders.

65. What did the doctor prescribe to the sick geologist? Tech-tonic.

66. Why was the geologist puzzled at the comedy show? Because some of the funny jokes fluorite over his head.

67. Did you see the geologist towing a crate of rocks behind his car? He had a wide lode sign.

68. What do geologists use to clean themselves? Soapstone.

69. Why was the geologist agitated? Because he had lost his marbles.

70. Why don’t geologists argue? Because they’re too pelite.

71. Why shouldn’t you lend a geologist money? Because they consider a million years ago to be recent.

72. You rock my world

73. Let’s rock and roll

74. Between a rock and a hard place

75. Power to the pebble

76. Pebble to the metal

77. Rock solid advice

78. Rock steady

79. Rock on

80. I need some assi-stones

81. Not to quarry

82. Rocky road

83. Quarried sick

84. Getting off to a rocky start

85. Rock the boat

86. On the rocks

87. Opportunity rocks

88. Solid as a rock

89. Don’t take me for granite

90. It’s a hard rock life

91. Hit rock bottom

92. Stony faced

93. A stony silence

94. Feeling sedimental

95. Feeling a little boulder

96. I won’t gravel

97. A clean slate

98. Rock solid plans

99. For the crater good

100. I lava you so much

101. Metamorphically speaking

102. You’re a gem

103. May the quartz be with you

104. Of quartz it is

105. Geode bless you

106. Geode willing

107. Geode forbid

108. An act of geode

109. I don’t want to chalk about it

110. Chalk it up to experience

111. Look who’s chalking

112. Keep your coal

113. Coal as a cucumber

114. In coal blood

115. Get coal feet

116. Gave me the coal shoulder

117. Shale of the century

118. Shale we dance?

119. Seek and ye shale find

120. I get the schist of it

121. All ore nothing

122. Believe it ore not

123. Be there ore be square

124. Now ore never

125. Heads ore tails

126. Friend ore foe

127. Give ore take

128. Don’t flint-ch

129. Igneous is bliss

130. A grain of basalt

131. A basalt on the senses

132. Have a gneiss day

133. Gneiss to meet you

134. Gneiss going

135. No more Mr. Gneiss Guy

136. This rock was magma before it was cool

137. A cold as stone

138. Turned to stone

139. Stepping stone

140. No stone unturned

141. A heart of stone

142. Rocks in your head

143. A pebble person

144. Cobble something together

145. A plutonic relationship

146. Gravelling at my feet

147. Rock around the clock

148. App-rocks-imate

149. My per-rock-ative

150. “I really like rock puns.” “My sediments exactly!”

And there you have it – we’ve left no stone unturned in our quest to find you the perfect rock joke. Hopefully they have put a rock solid smile on your face 🤣

For more family-friendly jokes and good puns, head this way:

Catherine

Source link

I mentioned it to my partner Fred and one day, months later, he came home and said he found a company nearby that sold used shipping containers. He was excited to explore building with it as he’s a traditional builder of commercial and residential structures.

2) How/where did you find the shipping container? (I wouldn’t know where to start!) And how much does something like that cost?

We found a company that sold used shipping containers in Newburg, NY (A-Verdi). It’s a 40’ foot container with 9’ high ceilings.

3) Was it hard to get it to your house?

The company delivered it on a flat bed.

(sent you pic)

4) Did you have to prepare the ground first before building the structure?

The first thing was to decide what we were building. We decided we’d build a barn to store construction tools/materials. The hayloft is where we store lumber. Also how useful would it be if it was moveable? We cut it in half to create two 20’ long storage areas with space in the middle for our boat. Before the company delivered the container, we leveled the area and poured Item 4 on top. This is a mix of stone made specifically to be compacted. It’s often used for driveways, parking areas, etc.

(sent you pic cutting container in half and using compacter tool on stone).

5) Where is this on your property?

This is opposite our vegetable garden and can be seen from our kitchen window

6) What inspired the exterior look? Was there a specific barn or images that you looked to?

I designed our vegetable garden fence nodding to chinoiserie and our home is a modern style farmhouse so this structure had to relate to those things. I toyed with doing a Union Jack design on the barn doors but chose this simpler look because there’s a lot going on with the garden fence across the way!

(Sent you pic of barn through fencing)

7) What color is it painted? Are you going to paint the exterior of the containers (inside the barn)? Looks like they’re unpainted based on the pictures.

It’s Benjamin Moore Dash of Pepper and I chose it because it helps the barn blend into the landscape. I also kept the interior cavity walls as is on the shipping container—that color and signage! One of the fun things about a reuse project is seeing at once what it was and what it is.

8) What is the roofing material?

Standing seam metal roof

9) Is it insulated?

It isn’t but we recently decided to turn one of the storage bays into a home gym. We plan to cut a hole on the side facing the creek on our property and we’ll install glass doors. We’ll be insulating it and adding heat.

10) How much did this project cost? Can be ballpark. And would be neat to get a sense of just materials cost vs. labor.

The container cost about $2000. We had leftover stone and wood we used for the construction. The biggest expense was the roof, around 10K. It’s hard to estimate labor as we did it ourselves over a year+ period in between client work.

11) Biggest challenge?

As amazingly sturdy as these structures are, once you cut into it, it needs a good bit of reinforcement. Our barn was never more sturdy than when we built the roof.

12) Biggest surprise?

We move the entire finished structure with chains hooked up to our skid steer. I didn’t expect it to be so light after it was built.

13) What do you use this building for?

Storage for building materials, boat and eventually a home gym

(Visited 1 times, 1 visits today)

What happens when a Japanese-style garden meets the southern California desert? For the very Zen results, let’s visit a serene gravel courtyard that landscape architecture firm Terremoto designed for Mohawk General Store in Santa Monica.

Photography by Caitlin Atkinson, courtesy of Terremoto.

“This was an attempt to create a garden that was both Japanese and desert simultaneously,” landscape architect David Godshall says, adding that client Kevin Carney wanted a space to have movie screenings and to create a backdrop for fashion shoots.

The garden, formerly occupied by gardening shop Potted, had existing hardscape (some concrete slabs) and a few specimen plants—including two large palms—that the team salvaged from the previous design. “For the rest of it, we started from scratch.”

“We made the design process conversational,” Godshall says. “We went cactus shopping with the clients. Then we went boulder shopping. After we got all the elements on site, an incredibly hardworking crew shadow boxed them into place. Then there was a lot of looking at how things looked, walking around, and shifting it around.”

Carol Verhake gardens in Berwyn, Pennsylvania (Zone 7a), and after two years without getting any snow, she got a beautiful snowfall this winter. Here are some shots she took of the garden looking beautiful under its white blanket. If you want to see her garden during the growing season, check out this post: Carefully Chosen Colors Bring a Garden Together.

Ampelaster carolinianus (climbing aster, Zones 7–9) is primarily a fall bloomer, but with mild weather it can stretch right into the winter and, as here, have flowers topped with snow.

Autumn fern (Dryopteris erythrosora, Zones 5–8) is evergreen in the warmer end of its range, and the fronds look amazing topped with snow.

Autumn fern (Dryopteris erythrosora, Zones 5–8) is evergreen in the warmer end of its range, and the fronds look amazing topped with snow.

Beautyberries (Callpicarpa spp.) have gorgeous purple berries in the fall that often last well into the winter, as some birds prefer them after a freeze or two has softened them up. That’s good for the birds, as they provide food for later in the season, and it’s good for the gardeners, as they get to enjoy the lovely berries for a long time.

Beautyberries (Callpicarpa spp.) have gorgeous purple berries in the fall that often last well into the winter, as some birds prefer them after a freeze or two has softened them up. That’s good for the birds, as they provide food for later in the season, and it’s good for the gardeners, as they get to enjoy the lovely berries for a long time.

Cryptomeria (Japanese cedar, Zones 5–9) looks beautiful in the snow. It’s hard to beat the classic beauty of conifers in the winter.

Cryptomeria (Japanese cedar, Zones 5–9) looks beautiful in the snow. It’s hard to beat the classic beauty of conifers in the winter.

Edgeworthia (Zones 7–10) produces these large, beautiful heads of flower buds in the winter that push open into incredibly fragrant yellow blooms in very early spring.

Edgeworthia (Zones 7–10) produces these large, beautiful heads of flower buds in the winter that push open into incredibly fragrant yellow blooms in very early spring.

Snowy winter days often show off garden structures and art at their very best. Here a trunk of a dead rhododendron has new life as a sculpture topped with a Moravian star.

Snowy winter days often show off garden structures and art at their very best. Here a trunk of a dead rhododendron has new life as a sculpture topped with a Moravian star.

This beautiful structure made from fallen limbs is what Carol calls her “love shack.” It is always beautiful, but wow does it look great in the snow!

This beautiful structure made from fallen limbs is what Carol calls her “love shack.” It is always beautiful, but wow does it look great in the snow!

One of the most dramatic features in Carol’s garden is her stone moon gate, and it is also looking its very best in a snowy landscape.

One of the most dramatic features in Carol’s garden is her stone moon gate, and it is also looking its very best in a snowy landscape.

Witch hazels (Hamamelis spp., Zones 5–9) are great winter bloomers. These cherry yellow blooms can take freezing temperatures and snow without missing a beat.

Witch hazels (Hamamelis spp., Zones 5–9) are great winter bloomers. These cherry yellow blooms can take freezing temperatures and snow without missing a beat.

Have photos to share? We’d love to see your garden, a particular collection of plants you love, or a wonderful garden you had the chance to visit!

To submit, send 5-10 photos to [email protected] along with some information about the plants in the pictures and where you took the photos. We’d love to hear where you are located, how long you’ve been gardening, successes you are proud of, failures you learned from, hopes for the future, favorite plants, or funny stories from your garden.

Have a mobile phone? Tag your photos on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter with #FineGardening!

Do you receive the GPOD by email yet? Sign up here.

GPOD Contributor

Source link

We work so hard to make our landscapes look incredible during the growing season. Why neglect them in the winter?

Dogwoods can provide an easy way to add a little color and shape to an otherwise bland space.

If you’ve ever stared out of a window at a garden that once was a riot of flowers and foliage, only to be miserably greeted by bare ground and dead plant material in the middle of February, you know how important a little colorful interest can be.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

And dogwoods don’t just add color to the garden. You can collect the stems and use them in floral arrangements indoors to liven up your interiors, too.

That would be enough to recommend them, in my book. But as an added bonus, they can be exceptionally beautiful during the warmer months as well.

In other words, they are truly the type of plants that offer four seasons of excitement in the landscape.

We’ll look at 15 exceptional options in more detail. Here’s the lineup:

All dogwoods perform better if you trim off some of the older stems to make room for the new growth, which tends to have brighter colors.

They also have the brightest hues when grown in full sun even though most can tolerate some shade.

You can learn more about growing dogwoods in our guide.

Without further ado, let’s start with a fiery option:

In Zones 3 to 7, C. sericea Arctic Fire® or ‘Farrow’ lives up to its name, with fiery red twigs on a dwarf plant that stays under four feet tall and wide.

Unlike the species, it doesn’t sucker, so you aren’t going to have to fight to keep it under control.

Dark green leaves pop out in the spring, followed by white flowers that give way to white berries. Use it as an informal hedge or display it in a large container to highlight the winter color.

You can bring one home from Nature Hills Nursery as a three- to four-foot bare root or a live plant in a #3 container.

I’m particularly fond of the stems on C. sanguinea ‘Cato,’ also known as Arctic Sun®.

Released in 2009 and hardy in Zones 3 to 9, the stems have a beautiful ombre of crimson at the tips, gradually transitioning to yellow at the base.

It looks like a warm sunset in the middle of the most colorless time of year.

The green leaves turn golden yellow in the fall, with white drupes as an accent.

In the spring, star-shaped white flowers – actually leaf bracts – appear in clusters all over the dwarf four-foot-tall and wide shrub.

Visit Nature Hills Nursery for a plant (or two) of your own.

There are lots of red-stemmed dogwoods out there, but few can rival the fiery scarlet hue of C. sericea ‘Bailey.’

Even without its medium green leaves, it makes a massive statement in the winter, with the stems stretching 10 feet tall and wide, or even a bit wider.

In the spring, white flower clusters decorate the ends of the branches, followed by bluish berries.

The autumn leaves take on a reddish-purple hue, but honestly, you’ll be rooting for them to fall so you can enjoy the bare stems.

Nature Hills Nursery has this bold bush available in three- to four-foot bare roots, or live plants in #3 or #5 containers. Grow it in Zones 3 to 9.

If you have a large area that needs some brightening up, get your hands on ‘Bud’s Yellow.’

This C. sericea cultivar will spread up to eight feet tall and wide, and it will send out suckers to start new plants.

Perfect for those slopes or streambanks that need some support and some color as well, the bright yellow stems are so vibrant they almost look neon.

This variety is also disease-resistant, so you don’t have to worry about fungal issues marring the medium green foliage.

Enjoy white flowers in the spring and snowy berries in the fall, accompanied by cheery yellow foliage.

Bring home a three- to four-foot bare-root or a live plant in a #3 container from Nature Hills Nursery for growing in Zones 2 to 8.

When this plant was developed at the University of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum in Chanhassen, Minnesota, in 1986, they picked an excellent name.

The cardinal red stems on this 10-foot-tall and wide shrub offer a vibrant contrast to winter gray and snow.

The fragrant white flowers are followed by cream-colored fruits in the fall, when the foliage turns deep purple. It’s a fabulous option for growing in Zones 3 to 8.

Visit Nature Hills to pick up a four- to five-foot bare-root or a live plant in a #3 container.

Bringing a bit of spice to the humdrum dormant landscape, C. amomum ‘Cayenne’ stands apart from some other dogwoods because its bright red stems will hold their color even in warmer regions.

With green leaves that turn orange-red in the fall, highlighting the pale blue berries, it makes a suitable addition whether you want to mitigate erosion or just add some color to the garden.

This shrub is both canker- and Japanese beetle-resistant. It grows rapidly to about six feet tall and 12 feet wide.

Want to add some spice to your life? Head to Nature Hills Nursery for some ‘Cayenne.’ It grows well in Zones 4 to 9.

A variegated cultivar of Tartarian dogwood, Creme de Mint™ (C. alba ‘Crmizam’) has medium green leaves with cream edges. In the fall, the foliage takes on a pinkish-red hue.

Once the leaves fall to the ground, bright chartreuse stems add some color to the landscape.

The white spring flowers will attract bees and butterflies, and the fall berries in bluish-white will feed the birds that visit your yard.

And this shrub won’t become overbearing, staying at a petite five feet tall and wide. It won’t sucker and spread where you don’t want it either.

Add a hint of mint to your garden by visiting Nature Hills Nursery for a live plant of your own, for growing in Zones 3 to 8.

Beautiful C. alba ‘Baihalo,’ known commonly as Ivory Halo®, is a delight from spring through fall with its dark-green foliage edged in ivory white, along with yellowish spring flowers and bluish-white fruits in the fall.

But as beautiful as the foliage is, you’ll be counting down the days until those leaves turn purple-red in the fall and drop to the ground so you can enjoy the vibrant red branches.

Just picture how much they will stand out against the winter snow in Zones 3 to 7.

This dwarf shrub stays at about six feet tall and wide at maturity, and while it will spread via suckers, it isn’t as prolific as some of its relatives.

In garden design, you always want a few elements of dark black or brown to anchor an area. A Tartarian dogwood cultivar, C. alba ‘Kesselringii’ is just the thing for the job.

In the spring, summer, and fall, the dark red stems act as a dramatic focal point underneath the medium-green leaves.

But it’s even more dramatic when the stems turn dark purple in the winter, acting as a visual anchor whether your landscape tends towards greens and browns or snowy white.

This fast-growing shrub will reach six feet tall and wide within the first year after planting, and it’s decorated in yellowish blossoms in the spring and sometimes into the summer, as well.

In the fall, the foliage transitions to a beautiful burgundy hue.

This all-season pleaser is suited to a wide range of climates in Zones 2 to 7.

Okay, hear me out. Pacific dogwood (C. nuttalli) doesn’t have the bright yellow or red stems that make other species so popular in the winter landscape.

But don’t pass over this option if you live in Zones 7 to 9, where you might not have long periods of snow but you still crave some winter interest.

The white or pinkish-colored flowers are much showier than anything on this list, coming in at nearly three inches in diameter.

They appear once in the spring and again in the early fall, followed by orange or pink drupes that persist on the tree well into the winter until the wildlife devours them.

That’s part of what makes this 20- to 40-foot-tall tree an excellent display option in the dormant season.

Combined with the reddish bark and branches that take on a gracefully arching habit, it makes an architectural statement rather than a more colorful one.

Planted en masse, the aptly named C. alba ‘Prairie Fire’ looks like a field of flaming eight-foot-tall and wide shrubs highlighted against the winter snow.

But what makes it particularly special isn’t just the bright red winter twigs or the beautiful cream flowers, followed by white berries.

The bright golden and red fall foliage also sets it apart from many other dogwoods, which tend to be a little lackluster in the autumn.

In the spring, it’s equally attractive with its golden-yellow foliage. Grow it in Zones 2 to 7.

C. sericea adapts to climates in just about every part of the US except the warmer areas of Florida, Texas, California, and Arizona.

It can be grown in Zones 2 to 8, and is native to southern Canada, and the northern and western US.

This shrub will grow up to 12 feet tall and 14 feet wide, spreading via suckers.

While it’s hard to beat the bright red winter color, it’s nothing to sneeze at during the rest of the year.

The creamy white blossoms are long-lasting and gradually give way to clusters of white berries. The silky, medium-green leaves change to hues of red varying from rust to burgundy.

While these dogwoods can tolerate some shade, the bark color will be muted outside of full sun.

Fast Growing Trees has this beloved species available in quart, two-gallon, or three-gallon pots, in single or four-pack quantities.

C. alba is commonly known as Tartarian or white dogwood. It’s native to Siberia, northern China, and the Korean peninsula, where it grows as a small tree or large shrub.

Beloved for its red stems and vigorous growth habit, it can reach 10 feet tall and wide.

The oblong leaves are medium-green, with creamy-white blossoms and white berries. The fall foliage is bright red and orange.

Unlike the US native C. sericea, this species doesn’t tend to send out as many suckers – which may be a good or a bad thing, depending on your needs. It’s hardy in Zones 2 to 7.

A Tartarian dogwood cultivar, C. alba ‘Elegantissima’ is the definition of a year-round performer.

In the spring, the variegated medium green and creamy gold leaves emerge, along with white flowers. In the fall, white berries cover the shrub in clusters, highlighted against the orange, red, and gold foliage.

After everything drops to the ground, the rosy red stems are left behind to brighten up the garden in Zones 3 to 8.

Make sure you have the space for this plant, which grows 10 feet tall and wide, producing suckers that allow it to spread.

Make one yours by visiting Nature Hills Nursery.

Yellow twig dogwood (C. sericea ‘Flaviramea’) is appreciated in the garden for its dark green foliage, white flowers, and white fruit, but it’s the bare winter twigs that really stand out.

They have a bright golden-yellow hue that beams, contrasting with winter snow like a ray of sunshine.

When mature, it can grow to six feet tall and just a touch wider, and the plant will spread via suckers as much as you’ll let it.

That makes it perfect for areas that you want to fill in with color, or spots that could use some erosion control, like stream banks and slopes.

It’s not quite as winter-hardy as the species, growing in Zones 3 to 7.

Head to Fast Growing Trees to purchase individual plants or four-packs of two- to three-foot or three- to four-foot live shrubs.

Whether you live somewhere snow-covered from December through March or you want to add some spice to a bland, gray garden, dogwoods fit the bill.

Which one of these sounds like the right one for your landscape? Let us know in the comments. And be sure to tell us if we missed one that you’re particularly fond of.

Now that you’ve sorted out the winter interest, you might be interested in learning more about dogwoods, like how to deal with problems, or choose a few others for your garden. If so, here are some guides worth checking out:

Kristine Lofgren

Source link

Julie shares about her experience with making fetid swamp water in Singapore:

When I used to live in Singapore, every Chinese New Year, when the cookies, crackers, snacks and mandarin oranges were finished, my local community garden would collect all of the plastic tubs and fruit peels from the community and buy some brown sugar and black-strap molasses in bulk, to make an enzyme liquid to use in our garden. It took months, but the longer you leave it, the better it gets. So we had loads left over from the year before, and we used in regularly, diluted down in water to spray on the soil and as a foliar spray too, to help our plants and trees thrive. The only thing you had to remember to do was ‘burp’ the tubs regularly, so gas didn’t build up and make them explode!

That comment was posted below my video on growing sunn hemp.

The JADAM version of Korean Natural Farming practiced by Youngsang Cho does not use sugars in fermentation; however, we have seen others use it, just as Julie relates.

Anaerobic composting isn’t the devil it’s made out to be. It can be very useful, especially when you have limited resources and wish to make the most of a small amount of fertile materials.

Of course, if you take the Dave’s Fetid Swamp Water approach and start using your anaerobic “tea” only a couple of weeks after you start the fermentation process, the stench is incredible.

It creates an aroma so thick you can feel the clouds of odor pressing against your body as you walk through the garden, which then condense into sulfurous snakes that creep directly through your nostrils into your brain.

If you get it on your hands, woe unto thee!

The noxious fumes persist for a day or more on the skin, even after scrubbing your way through a fresh bar of Zest. If you caress your spouse’s hair, she’ll recoil in horror and wonder if you are a reanimated corpse instead of the man she married. If you pet a puppy, it will burst into flames, giving you a memory you’ll recall with shame and horror for the rest of your life.

It’s that bad.

Yet plants don’t have noses and they do just fine with it, happily growing amidst the fumes.

It’s much better if you wait longer to use it, until it’s burned off the worst of the aromas. And if the Singaporeans are right, it just gets better for the garden.

I’ve smelled year-old swamp water made from fish guts and it was not unpleasant. I’ve also had a batch of mixed manure and weeds and other materials (including chicken guts) that mellowed out into a mild soy sauce aroma.

All this reminds me – it’s almost spring and we need to make a batch.

(You can learn more about “Dave’s Fetid Swamp Water” in Compost Everything.)

Ever wondered why spending time outdoors is so important for children’s mental health? This article by children’s wellbeing author and psychotherapist Becky Goddard-Hill will help you understand the powerful impact playing outside can have on a child’s mood and wellbeing.

Becky is the author of the brand new book ‘How I Feel’, a feelings-focussed activity book for children aged 3-7. Its primary aim is to encourage younger children to become more emotionally literate and better able to both understand and manage their feelings.

The book contains 40 play-based activities to help young children talk more coherently about their emotions, encouraging them to be kinder, happier, calmer, and braver. It aims to encourage self-belief and growth mindset and help children to understand and manage their feelings better.

It’s beautifully illustrated and packed full of lovely things to do. It has been written so children in KS1 will be able to read a lot of it themselves, and it contains lots of great parenting tips too.

Here Becky shares why encouraging kids to get outside matters so much for a child’s mental health.

1. Stress Reduction: Spending time outdoors has been shown to reduce stress levels and promote relaxation, leading to improved mental well-being.

2. Increased Vitamin D: Sunlight exposure helps the body produce vitamin D, which plays a crucial role in mood regulation and may reduce the risk of depression.

3. Enhanced Cognitive Function: Outdoor play stimulates creativity, problem-solving skills, and cognitive development, contributing to overall mental resilience.

4. Improved Mood: Physical activity and exposure to nature release feel-good chemicals in the brain, such as endorphins and serotonin, which can uplift mood and combat feelings of sadness or anxiety.

5. Connection with Nature: Time spent in natural environments fosters a sense of connection with the world around us, promoting feelings of peace, wonder, and gratitude.

6. Social Interaction: Outdoor play encourages social interaction, cooperation, and communication skills, which are essential for healthy emotional development.

7. Reduction in ADHD Symptoms: Research suggests that outdoor activities may help reduce symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and improve focus and attention span.

8. Resilience Building: Overcoming challenges and experiencing risks in outdoor environments helps children build resilience and coping skills, preparing them to navigate life’s ups and downs.

In summary, encouraging children to spend time outdoors is essential for their mental health and well-being. By providing opportunities for outdoor time, exploration, and connection with nature, parents and caregivers can support children’s holistic development and help them thrive emotionally and mentally.

*How I Feel is available from all good bookshops and is out now.

Catherine

Source link

Living in a city, your gardening options can be limited. So our interest was piqued when a friend shared a video from Plant Traps. In it, a woman hooks a minimalist wire contraption onto a metal railing to create a support for a potted plant. The mechanism was delightfully simple, removable—and it absolutely transformed the space with greenery.

We reached out to Plant Traps founder Deborah Holtschlag to inquire about her ingenious device, and it turned out that we were among several million people who’d recently found her RailScapes Plant Clip. Since debuting her invention last March, Holtschlag has been hustling to create Instagram Stories and TikTok videos to promote it, but it wasn’t until two days after Christmas that one went viral. “The Reel on Instagram that got 100 million views was a blessing, but we also blew through our reserves,” Holtschlag says. (Don’t worry, they’re finally caught up on inventory.)

We’re not shocked that Holtschlag found gardeners hungry for her plant support. Often the products sold to hang plants from railings are ugly, require drilling, or only work on certain types of fences. Her version uses tension to sit between railings (rather than draping over the top), and it can be adjusted to fit at a variety of railing widths. Renters can take it with them when they move—and at $20 a piece, it is relatively affordable.

What did come as a surprise was that Holtschlag herself is not a gardener herself. It turns out she invented the product for her gardener husband, whose plants were taking up what she considered to be too much of their precious space patio.

Since launching the RailScapes Plant Clip, Holtschlag says she has been thrilled to see her customers use them in many ways, including on gates, spiral staircases, wood fences with wide-spaced pickets, and, as seen in her second most popular Reel, on an indoor stair railing.

Personally, this writer is looking at the bare wrought iron fence outside her window in a whole new light.

See also:

(Visited 1 times, 1 visits today)

This is Barb Mrgich, Master Gardener from Adams County, Pennsylvania. I have sent in several entries in the past. (Butterflies in Barb’s Garden and Barb’s Favorite Photos ) I love lots of color in my gardens. In January, Joseph did an entry on yellow in the garden, and it inspired me to submit these photos. I really like his description that yellow flowers are “floral sunshine.” A little floral sunshine is never more appreciated than in the very early spring when things are looking rather dull and dreary! Although I like to consider myself a wildlife and native-plant gardener, I still rely on select nonnatives for beauty and color in the early season since I have found that most of my native plants shine better in midsummer and fall. All of these pictures were taken in mid-April in my Zone 6B garden.

If you are interested in adding some bright early accents to your landscape, here are some of my favorites.

This shrub is golden euonymus (Euonymus japonicus ‘Aureo-marginatus’, Zones 6–9). It likes some shade and is quite drought tolerant. A fast grower, it will reach 5 feet tall if you don’t prune it. Some people sheer this plant into a meatball. I simply take my clippers and cut back some of the taller branches. Golden euonymus will hold its leaves and look like this all summer, fall, and winter. It makes nice additions to indoor and outdoor flower arrangements—even in the winter!

A lovely bright Hosta (Zones 3–9) has leaves edged with green. I have no idea of the exact cultivar, but there are many to choose from. This one is just getting started. It will get much larger and stay bright in its slightly shaded spot all summer.

A lovely bright Hosta (Zones 3–9) has leaves edged with green. I have no idea of the exact cultivar, but there are many to choose from. This one is just getting started. It will get much larger and stay bright in its slightly shaded spot all summer.

These small shrubs are Deutzia ‘Chardonnay Pearls’ (Zones 5–8). They do well in partial or full sun. (If in too much shade, they will lose their color.) I have them in front of two dark, red-leaved ninebark ‘Summer Wine’ (Physocarpus opulifolius ‘Summer Wine’, Zones 2–8), and I love the combination. ‘Chardonnay Pearls’ blooms in spring. It should be sheered just after it blooms.

These small shrubs are Deutzia ‘Chardonnay Pearls’ (Zones 5–8). They do well in partial or full sun. (If in too much shade, they will lose their color.) I have them in front of two dark, red-leaved ninebark ‘Summer Wine’ (Physocarpus opulifolius ‘Summer Wine’, Zones 2–8), and I love the combination. ‘Chardonnay Pearls’ blooms in spring. It should be sheered just after it blooms.

Angelina sedum (Sedum rupestre ‘Angelina’, Zones 5–8) is a bright ground cover that will fill in an area very quickly. It is not at all fussy about anything. It welcomes sun or shade. In the shade it is more green, but still attractive. Drought doesn’t bother it one bit. It is evergreen. It will darken a little in the winter but will still be very much in evidence.

Angelina sedum (Sedum rupestre ‘Angelina’, Zones 5–8) is a bright ground cover that will fill in an area very quickly. It is not at all fussy about anything. It welcomes sun or shade. In the shade it is more green, but still attractive. Drought doesn’t bother it one bit. It is evergreen. It will darken a little in the winter but will still be very much in evidence.

Weigela ‘Eye Catcher’ (Zones 5–9) is definitely eye-catching. This one is also just now leafing out. I love its variegated foliage. I like seeing the stand of white daffodils peeking through it.

Weigela ‘Eye Catcher’ (Zones 5–9) is definitely eye-catching. This one is also just now leafing out. I love its variegated foliage. I like seeing the stand of white daffodils peeking through it.

This is what Weigela ‘Eye Catcher’ looks like a little later, when the leaves are fully out and flowers are opening. Spring is definitely its best season. As the summer wears on, it suffers, and the leaves wither some. It definitely needs a little bit of shade. It would probably benefit from more regular irrigation, but I don’t do that. The blue flowers in this picture are ‘Walker’s Low’ catmint (Nepeta ‘Walker’s Low’, Zones 4–8).

This is what Weigela ‘Eye Catcher’ looks like a little later, when the leaves are fully out and flowers are opening. Spring is definitely its best season. As the summer wears on, it suffers, and the leaves wither some. It definitely needs a little bit of shade. It would probably benefit from more regular irrigation, but I don’t do that. The blue flowers in this picture are ‘Walker’s Low’ catmint (Nepeta ‘Walker’s Low’, Zones 4–8).

Let’s not forget the tulips! I love these bright yellow tulips with the red stripe. I brought some into the house, and, of course, the warmth encouraged them to open up wide. These tulips originally came from Hershey Gardens, where they give away bulbs to volunteers who are willing to dig them up and carry them away. These are in the group of tulips called Darwin hybrids, which are some of the best for perennializing. These were planted over 20 years ago, and they are still going strong!

Let’s not forget the tulips! I love these bright yellow tulips with the red stripe. I brought some into the house, and, of course, the warmth encouraged them to open up wide. These tulips originally came from Hershey Gardens, where they give away bulbs to volunteers who are willing to dig them up and carry them away. These are in the group of tulips called Darwin hybrids, which are some of the best for perennializing. These were planted over 20 years ago, and they are still going strong!

Finally a native plant! This is golden ragwort (Packera aurea, Zones 3–8). It grows in my rain garden as a ground cover. It starts to bloom in April and continues through the month of May. When it is finished blooming, its nice big, shiny leaves cover the soil and do an excellent job of shading out the weeds.

Finally a native plant! This is golden ragwort (Packera aurea, Zones 3–8). It grows in my rain garden as a ground cover. It starts to bloom in April and continues through the month of May. When it is finished blooming, its nice big, shiny leaves cover the soil and do an excellent job of shading out the weeds.

Have photos to share? We’d love to see your garden, a particular collection of plants you love, or a wonderful garden you had the chance to visit!

To submit, send 5-10 photos to [email protected] along with some information about the plants in the pictures and where you took the photos. We’d love to hear where you are located, how long you’ve been gardening, successes you are proud of, failures you learned from, hopes for the future, favorite plants, or funny stories from your garden.

Have a mobile phone? Tag your photos on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter with #FineGardening!

Do you receive the GPOD by email yet? Sign up here.

GPOD Contributor

Source link

Gardening is, or at least should be, an ongoing learning process. It can include trial and error (and sometimes failure), but for me, the most exciting part is discovering new plants. When I find an unfamiliar plant, it’s pretty exciting, since I’ve grown nearly everything over the years and not much surprises me.

Trying out new plants comes with its risks, especially in our unpredictable northeastern climate. A species native to a dry desert or a cool alpine meadow may not perform as well in our hot and humid summers or cold, damp springs. Yet when a plant suddenly outperforms everything else you’ve planted in a container or garden, that is remarkable. Here are a few of my most recent remarkable plant discoveries. These plants include annuals and tender perennials, but I recommend trying them all as annuals if you live in the Northeast this summer.

Ursinia anthemoides ‘Solar Fire’, annual

How this plant ever escaped my radar still confounds me, but I believe it is a winner. Ursinia is a rarely grown annual native to South Africa, which gives us a hint about what conditions it loves—heat, well-drained soil, and full sun. I first ordered one of these plants via mail from a West Coast nursery to see if it might do well in an alpine trough that I had. Not only did it bloom like crazy, but it also grew much larger than I had expected, overtaking all of the alpine plants in just a single season.

It did so well that I decided to search for some seeds online, as I knew that it was a plant I was unlikely to find at any garden center in the Northeast. While this is one of those annuals that you will need to sow yourself (indoors, under lights, about 6 weeks before planting out), it’s easy enough to attempt and worth the extra effort.

Ursinia seedlings transplant easily; put them into 2-inch pots first, and after frost threats have passed, into containers or a prepared bed. I set about 6 to 8 plants into 11-inch pots, spacing them about 4 to 5 inches apart for a denser look, and the results were spectacular. Not only did they bloom prolifically (with flowers nearly covering the plant), but I gave some to a friend who lives on a rooftop in the city where the conditions are as harsh as any mountaintop, with blaring sun and relentless wind, and the plants did just as well.

On the downside, ‘Solar Fire’ ursinia has a shorter season than most annuals. My plants bloomed from early June until late July when they were done for the season, but the clouds of tangerine, daisylike blooms with burgundy eye marks above dark stems and ferny foliage made growing them worth the effort.

Calylophus cvs., Zones 8–10

When I came across a pot of Texas primroses at the garden center a couple of summers ago, I bought it. I felt it was my duty to trial this plant in my garden to encourage more unusual plants to be sold at our garden centers, and boy was I satisfied. The Ladybird® series of Texas primroses are hybrids that come with features that make them worth the extra cost per plant, including sterility (so that they keep on blooming and never form seed) and a remarkable tolerance for hot and humid weather like we get in the Northeast in summer—which is something that the straight species can’t deal with. Just one of these plants will spread to 20 inches wide, covering the ground or a single container with beautiful foliage and large flowers, blooming until frost. These are short-lived perennials in the Southwest; for us in the North, they are best treated as annuals. Cut them back a bit in late summer for extra vigor if the plants start to bloom less.

You’ll have to look for these plants at garden centers, as the two cultivars—Ladybird® Lemonade Texas primrose (Calyophus ‘WNCYLALEM’, Zones 8–10), which has light yellow flowers, and Ladybird® Sunglow Texas primrose (Calyophus ‘WNCYLASUN’, Zones 8–10), which has darker yellow flowers—are both propagated vegetatively (clonally, from cuttings) and are not available from seed. These plants are drought tolerant; I’d say that hellstrips or large containers are the best places for them.

Mimulus cvs.; syn. Diplacus cvs., Zones 9–10

Sticky monkeyflower might not be the most attractive name ever, but once you’ve grown this sensational series of plants you’ll agree that the name is something to overlook. Derived from the native Californian species (Mimulus aurantiacus syn. Diplacus aurantiacus, Zones 7–11), the Jelly Bean® series of hybrids is an exceptionally high-performing group.

Some of the great cultivars in this series include:

All of these perennials are worth the search. I’ve grown two of them, and both have been extraordinary, each covered with flowers from early spring through midsummer. The dark mauve flowers of ‘Jelly Bean Betabel’ have golden-orange colored throats and are a favorite of hummingbirds. ‘Jelly Bean Fiesta Marigold’ appealed to me with its unusual French marigold-colored flowers. I’m a sucker for strangely colored flowers.

Since the Jelly Bean® series doesn’t come true from seed, all plant material must be clonally propagated. While you are not likely to find these at your local garden center in the Northeast, there are several online sources.

Mecardonia ‘USMECA8205’, Zones 9–11

Mecardonia sounds more like a vacation resort island than an annual flower, but this plant pays off in dividends. The small, yellow flowers of GoldDust® axilflower are super cute and produce in such volume that they nearly cover the plant, continuing to bloom until frost. An annual blooming until frost is something that you often read about in seed catalogs, but it is not commonly experienced. GoldDust® axilflower started filling out my containers so well that by July I had rushed back to the garden center to see if maybe they had more. Sadly, they didn’t.

Native to the Americas, Mecardonia is a genus not often grown as ornamental, but this new hybrid is quite exceptional, and I hope that we see more introductions in the future. If you’re looking for a plant with a dense, mounding habit and one that truly blooms all season long, this is the one to seek out.

Silene pendula ‘Sibella Carmine’, annual

A few years ago I ordered ‘Sibella Carmine’ nodding catchfly seeds on a whim. I didn’t pay much attention when I sowed them, but most came up (under lights). After a few weeks I started to pay attention to some stocky, very healthy-looking seedlings that had lush, bushy growth, making me look like a seed-starting genius.

I repotted the seedlings, planting individual plants into 3-inch pots, which promptly filled with roots. I kept them growing under warm LED lights, and once the threat of frost had passed, I planted all of them together in an old whisky barrel where I sometimes planted herbs or a tomato. This is a plant that looks best planted en masse, with plants placed relatively close together (6 inches apart). The closer planting ensures a better show. Within a month, my plants had filled in and begun to bloom, extending until early August.

As Barbie-pink flowers began to pop open over the short 11-inch-long stems, the show was taking over the garden. This annual performs so well that it looks exactly like its picture in seed catalogs, almost as if you asked an AI art generator to create a “pretty pink flower in a container.” When I reread the description in the catalog, I discovered that ‘Sibella Carmine’ had won a coveted Fleuroselect Gold Medal for its great performance, which is totally deserved. You will have to order seeds of this plant and start them yourself, as few, if any, garden centers carry this selection.

Sometimes being uncommon in the trade increases the appeal of a plant, especially when it’s such a spectacular garden specimen. I don’t know about you, but if my neighbors and friends have never heard of something, it makes it all the more desirable to me. Any one of these selections will make a stunning centerpiece to your containers and borders this summer, adding something new that will push your designs to the next level.

For more exciting annuals, check out All About Growing Annual Plants. And for more Northeast regional reports, click here.

Matt Mattus is the author of two books: Mastering the Art of Flower Gardening and Mastering the Art of Vegetable Gardening. He gardens in Worcester, Massachusetts.

More summer blooms for Northeast gardens:

Matt Mattus

Source link

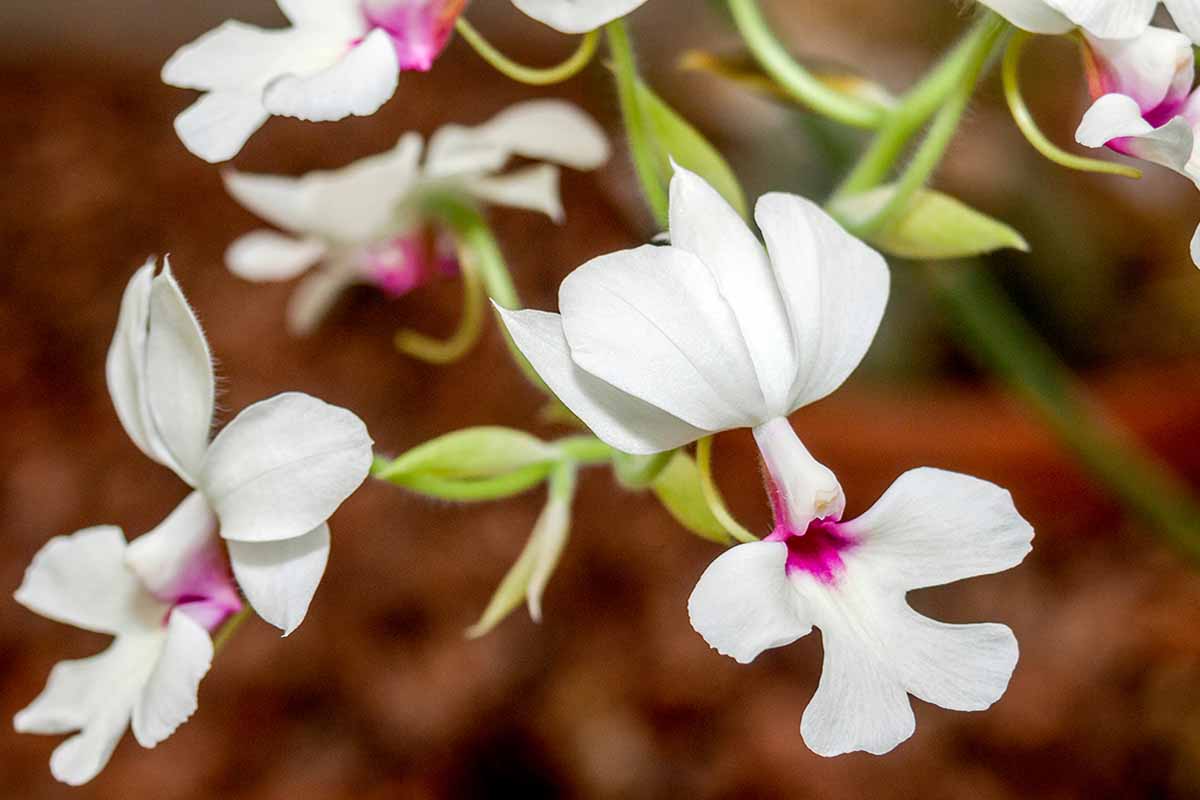

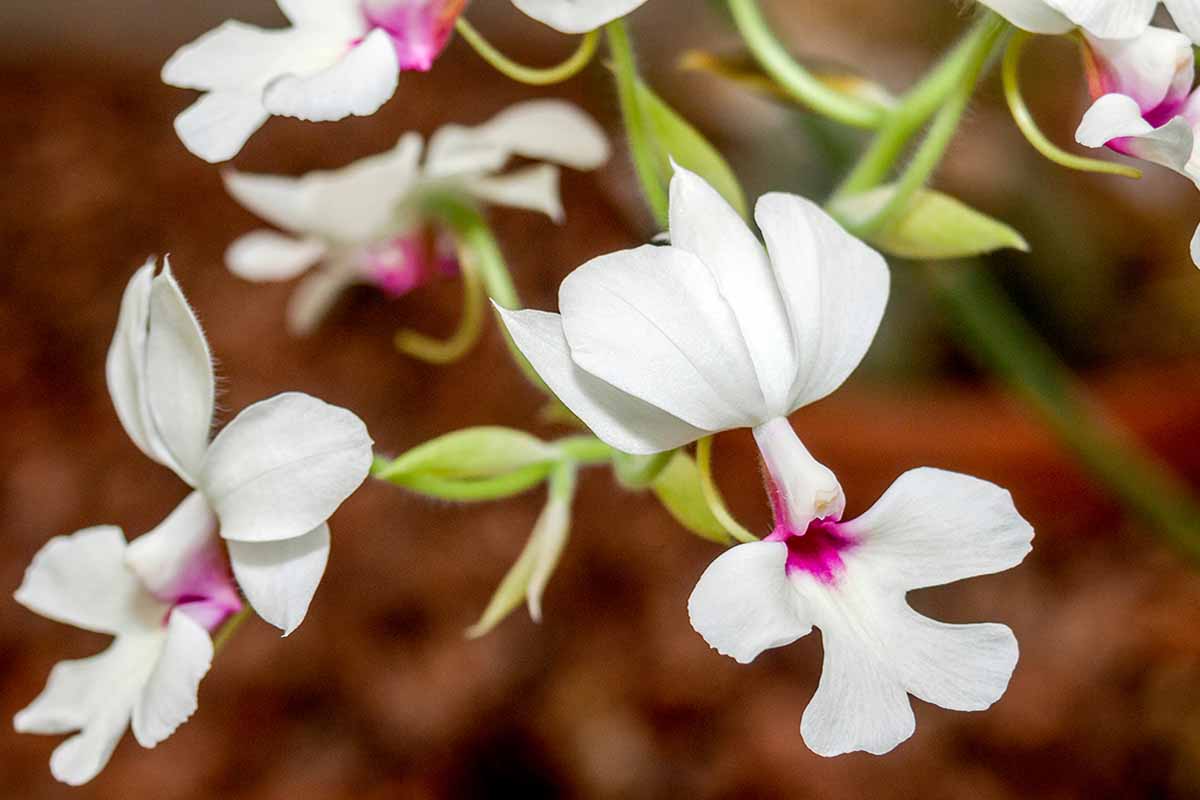

Never was there such an aptly named plant. The genus name Calanthe combines “kalos,” which is Greek for beautiful, and “anthe,” which is Greek for flower.

Sometimes known as Christmas orchids, species in this genus are adaptable, elegant, and colorful, with some hardy enough to withstand temperatures at or even below freezing!

They make excellent houseplants, like many orchids, but they can also be used in landscaping in Zones 6 and up.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I understand why Phalaenopsis orchids are so popular as houseplants, but I’m baffled as to why more people aren’t enjoying Calanthe orchids in their homes and yards.

They’re long-blooming, and some are hardier than your more common species. But they’re every bit as beautiful as moth orchids.

Interested in these glorious plants? We’ll help you master the growing process. Here’s what we’ll go over to make that happen:

Because they generally grow in the earth rather than attached to trees and rocks, Calanthe species have some unique characteristics and growing requirements.

Before we talk about those, let’s understand a bit more about what sets these plants apart.

Calanthe orchids (ka-LAN-thee) are those in the Calanthe genus, which comprises about 200 species.

They are mostly terrestrial plants that come in two types, defined by the subgenera Eucalanthe and Preptanthe.

Eucalanthe species are evergreen with a basal rosette of leaves and no pseudobulbs, with a flower stem that emerges from the center of the leaves. They grow in tropical to temperate areas.

Preptanthe plants are deciduous and lose their leaves in the cold winter of their preferred environments. The flower stalks form from pseudobulbs that are typically gray-green.

Evergreens include C. alismifolia, C. sylvatica, and C. triplicata, and deciduous species include C. hirsute, C. rosea, and C. vestita

You can’t breed the two different subgenera, which is one reason that botanists are considering separating the two into their own genera.

The difference is important because it impacts how you’ll grow these plants.

Home gardeners tend to prefer the deciduous types because they have long-lasting inflorescences that can stick around for months.

Regardless of the type, they are all sympodial, which means they produce multiple flower stalks rather than a single stalk. All have pleated or corrugated leaves and many have clusters of oval-shaped pseudobulbs.

They can be found growing wild across the globe in tropical climates in Asia, Australia, Mexico and Central America, the West Indies, and the Pacific Islands. The vast majority of species are native to southeast Asia.

Heads up: lots of orchids are known commonly as “Christmas” because it’s the name given to those that flower in the winter. But not all calanthe orchids bloom in the winter, and not all Christmas orchids belong to the Calanthe genus.

C. discolor and C. triplicata are commonly called Christmas orchids and bloom in winter.

The Calanthe genus was first described and illustrated by Georg Rumph, a German botanist, in 1750 in his tome “Herbarium Amboinense.” He used a specimen from Indonesia. The genus was formally established in 1821 by Robert Brown, a Scottish botanist.

Back in the 19th century during the Victorian plant craze, Calanthe orchids were a floral status symbol. Over the years, they have taken a backseat to Phalaenopsis and Cattleya, which is a shame. They’re easy to grow, long flowering, and showy.

One of the first orchid hybrids on record was a cross between C. furcata and C. masuca, bred by John Dominihy, a breeder who worked with James Veitch, who founded the famous Veitch Nurseries in England. It was called C. x dominii.

This was followed by a hybrid between C. rosea and C. vestita.

These days, while they haven’t gained the same level of popularity as their cousins, they are popular in their own right, with lots of hybrids and cultivars on the market.

If you’re up for an adventure, it’s possible to propagate orchids from seed.

Note that I said it’s possible, but not easy. It takes some special equipment and a lot of time, but you might be able to breed something exciting and new.

If you’re interested in the challenge, please visit our guide to propagating orchids from seed. Otherwise, let’s talk about division.

Both types can be divided, but Preptanthe plants actually grow better if you divide them regularly. That’s because two-year-old pseudobulbs die at the end of their second year. When you divide them regularly, you encourage new growth.

To divide, gently dig up a plant or pull it out of the container. Brush away the soil from the roots and locate a natural division in the plant that includes some roots and some pseudobulbs. Use a pair of clean scissors or pruners to sever the largest roots and then tease the plant apart.

If the plant has any back bulbs, which are the older bulbs that no longer have leaves, you can divide these and plant them individually.

Plant half back in the original pot or area of the garden and plant the remaining section in a new area or container.

Epiphytic orchids prefer that their roots be a bit crowded, but you can use larger containers with terrestrial species. Look for a container that’s about twice the size of the rootball.

Most of us purchase our first Calanthe orchids or receive them as a gift.

When you bring your first one home, you don’t need to repot it right away. But if you want to put it in the ground, it’s best to wait until mid-spring.

Prepare the ground by working in some well-rotted compost and making a hole twice as wide and the same depth as the growing container.

Gently remove the plant from its container and loosen up the roots. Lower it into the soil and firm the soil up around it.

The crown should be positioned at soil level or just below it. Don’t plant it more than just slightly below the soil surface or you run the risk of rot.

Gently water and add more soil if it settles too much.

Generally speaking, evergreens should be kept moist to damp year-round, and deciduous types need to be allowed to dry out when the leaves have fallen. Let the medium completely dry out until new growth starts to form.

Both types prefer humidity between 40 and 80 percent.

While this varies by species, most prefer temperatures in the 70s or 80s during the day and around 50°F at night.

Sticking to the cooler end of the spectrum will result in longer-lasting flowers. Evergreens can tolerate cooler temperatures, with most being hardy down to around 5°F.

Most need bright, indirect light indoors, and direct morning light is preferred. Outside, they do best in dappled shade or with an hour or so of direct morning light.

I will say that these plants can tolerate more light than most gardeners realize. Partial sun is perfectly fine for most species, so long as you expose them to the brighter light gradually over the course of a few weeks until they’re acclimated.

As with many houseplants that can tolerate bright light, growers cultivate these orchids in dimmer conditions than what’s ideal in order to acclimate them to the light available in most homes.

Without exception, mine have flowered better when I give them more light. Just avoid afternoon light, which is way too harsh.

Provide Preptanthe species grown indoors with a medium containing sphagnum moss, coconut coir chips, medium-size bark, and perlite. Don’t use a mix that is primarily orchid bark, which is marketed for epiphytes. You want some loam for the terrestrial orchids.

Outdoors, work a lot of well-rotted compost into the soil – the more the better.

The soil must be well-draining. If it isn’t, choose a container or a raised bed so you can control the medium and drainage. Or, if you have heavy clay, work in equal parts compost to the native soil at least two feet down and two feet out.

Either way, these plants prefer neutral soil, but they can tolerate a pH range between 6.0 and 8.0.

If you want to grow Eucalanthe species indoors, they must be exposed to temperatures just above 35°F for cool-growing species and 50°F for tropical species at night for two months to encourage new growth and blooming. That’s why most people grow them outdoors.

Keep in mind that while most Eucalanthe plants can grow as far north as Zone 6, some species are tropical and need warmer climates. Depending on the species, they need to be kept indoors during cold weather outside of Zone 9.

Outdoor plants don’t need a ton of fertilizer. Do a soil test and amend accordingly. Otherwise, you shouldn’t need to add fertilizer.

If you are growing yours in a container, change the soil every few years and fertilize once before flowering with a mild, balanced fertilizer.

Never fertilize a Preptanthe while it’s without leaves.

Resist the temptation to remove the leaves when they become crowded and untidy.

They are still providing vital nutrients to the plant, and removing them creates wounds that may expose the plant to viral pathogens. They shouldn’t be removed until they age to yellow and then brown and die off on their own.

Once the leaves turn yellow and collapse, you can remove them. They should just pull away, or you can use scissors to clip them off.

You can remove damaged or diseased leaves at any time.

For tropical types, aim for 50°F at night and 60°F during the day for a month or so to encourage reblooming.

To protect outdoor plants that go dormant, place two inches of mulch over the soil in the fall after the leaves die back. Use an organic mulch like leaf litter, shredded bark, or compost.

In USDA Hardiness Zones at the low end or even one below the recommended range of growing zones for a given species, it’s possible to keep plants alive with a thick layer of protective mulch. Make the mulch pile about a foot deep, covering the orchid and its root zone.

Remove the mulch in the spring when temperatures are regularly above freezing or if you see new growth emerging.

Container-grown outdoor orchids should be brought into an unheated garage or cold basement to overwinter.

Preptanthe orchids should be dug up and divided regularly. The pseudobulbs die after they’re two years old, so regular dividing will keep the plant going strong. Be extra careful when working with them because the pseudobulbs break easily.

It seems like new cultivars are popping up all the time, but you can’t go wrong with any of the species or their hybrids.

Here are just a few of the prettiest and easiest to grow in home gardens or indoors:

A popular evergreen or semi-evergreen in colder areas, the leaves of C. discolor can grow up to 18 inches long and form at the base of tall flower spikes dotted with up to 10 brown, white, green, and pale pink flowers.

This species grows indigenously in Japan, Korea, and China. It has become wildly popular as a house or garden plant and is often used as a parent for hybrids.

Kozu hybrids are absolutely well worth seeking out.

These hybrids are a cross of C. discolor and C. izu-insularis, and produce flowers in pink, purple, red, white, and yellow, depending on the cultivar.

‘Kozu Spice,’ for example, is an evergreen indoors or in Zones 7 to 9 or semi-evergreen in Zone 6.

It was bred in 1996 in Japan by K. Karasawa, and has large white and purple blossoms.

Native to Japan and Tibet, this species grows in mountainous regions. It has bright green and light yellow flowers on tall stalks.

Each 15-inch stalk can produce up to 10 flowers. A member of the Preptanthe subgenus, C. nipponica can be grown outdoors as far north as Zone 6.

This species was first described by Japanese botanist Tomitarô Makino in 1898, and it has become a popular option for breeding hybrids.

This Japanese evergreen has underground pseudobulbs bearing two or three leaves up to nine inches long and three inches wide at their largest.

Each plant will only develop four or five flowering spikes at a time. These can reach up to 13 inches in height and initially feature nodding buds that eventually open and face upward.

Plants can exhibit up to 25 white and purple, pure purple, or pure white flowers at a time and they may bloom all together or open sequentially, starting in July and lasting through September.

C. reflexa grows in warm areas in wet woodlands or along stream banks, which tells you that this is a plant that needs lots of moisture.

Hailing from Japan, this hardy evergreen has 18-inch tall inflorescences with bright yellow blossoms.

C. sieboldii is one of the largest plants in the genus and will survive temperatures down to 10°F.

While the flowers aren’t the showiest, they’re eye-catching in their own right.

Combined with the large, pleated leaves that resemble hostas, C. sieboldii is a beautiful garden option.