You might call them political progressives. Or maybe super progressives, given how much they want to reshape politics in Los Angeles.

Whatever the label, candidates on the left end of the political spectrum made crucial advances in the March 5 primary election for City Council, setting the stage for some hard-fought runoff campaigns and potentially, an expansion of their power by the end of the year.

Progressive activists and advocacy groups helped reelect City Councilmember Nithya Raman, while sending two other left-of-center candidates — tenant rights attorney Ysabel Jurado and small business owner Jillian Burgos — into runoffs against more moderate rivals.

“I think the results showed consistently across the board that when we show up, we win,” said Bill Przylucki, executive director of Ground Game LA, a nonprofit advocacy group that has spent several years pushing the council to the left.

If Burgos and Jurado prevail in November, the number of council members with deeply progressive backgrounds will grow from three to five, making up a third of the 15-member council. Four of the five have campaigned alongside Democratic Socialists of America-Los Angeles. Burgos, the fifth, drew support from other big names in leftist political circles, including City Controller Kenneth Mejia and former mayoral candidate Gina Viola.

A five-member super-progressive voting bloc would have significant influence over homelessness, subsidized housing, tenant protections, public transit, the installation of bike lanes and the size of the Los Angeles Police Department.

The bloc would need only three more votes to pass legislation on a council where several members, including Marqueece Harris-Dawson and Katy Yaroslavsky, are left-of-center swing votes. Super progressives also would occupy additional seats on the council’s committees, allowing them to shape policies from their inception, Przylucki said.

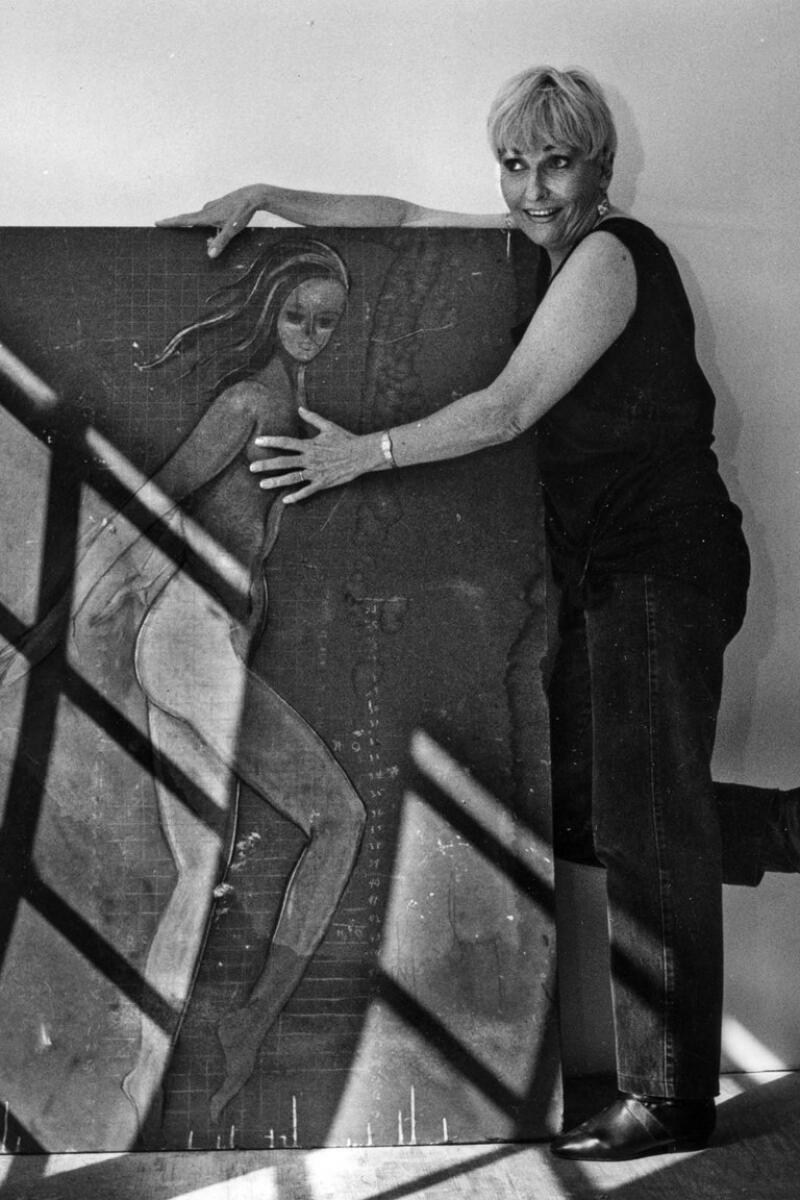

Los Angeles City Councilmember Nithya Raman speaks to the crowd on election night. She secured the majority vote needed to avoid a Nov. 5 runoff, winning a second term.

(Myung Chun/Los Angeles Times)

Some players in L.A. politics say the effect of the left in the primary is overstated. They point out that Councilmember John Lee, one of the council’s centrist members, easily won his reelection bid in the northwest Valley. Another incumbent, Councilmember Imelda Padilla, coasted to reelection after securing support from public safety unions, construction trade unions, Valley business groups and others.

Raman won 50.7% of the vote, securing the majority she needed to win outright. But that victory simply preserved the existing political makeup of the council, said Tom Saggau, spokesperson for the Los Angeles Police Protective League, which waged an expensive but unsuccessful campaign against Raman.

“At the end of the day, there’s been no net gain for any ideology on the council,” he said. “There’s still three socialists on the council. That was before the election, that was after the election.”

Saggau said the police union has not yet decided how it will spend its resources in the upcoming runoffs.

L.A.’s progressive groups remain hopeful that Jurado and Burgos will win and shift the status quo.

Julio Marcial, senior vice president of the nonprofit Liberty Hill Foundation, said that expanding the council’s super-progressive bloc would ensure that City Hall has a “real, honest conversation” about strategies for community safety. For Marcial, that means shifting money out of the LAPD and into affordable housing, expanded mental health services, job training and other programs.

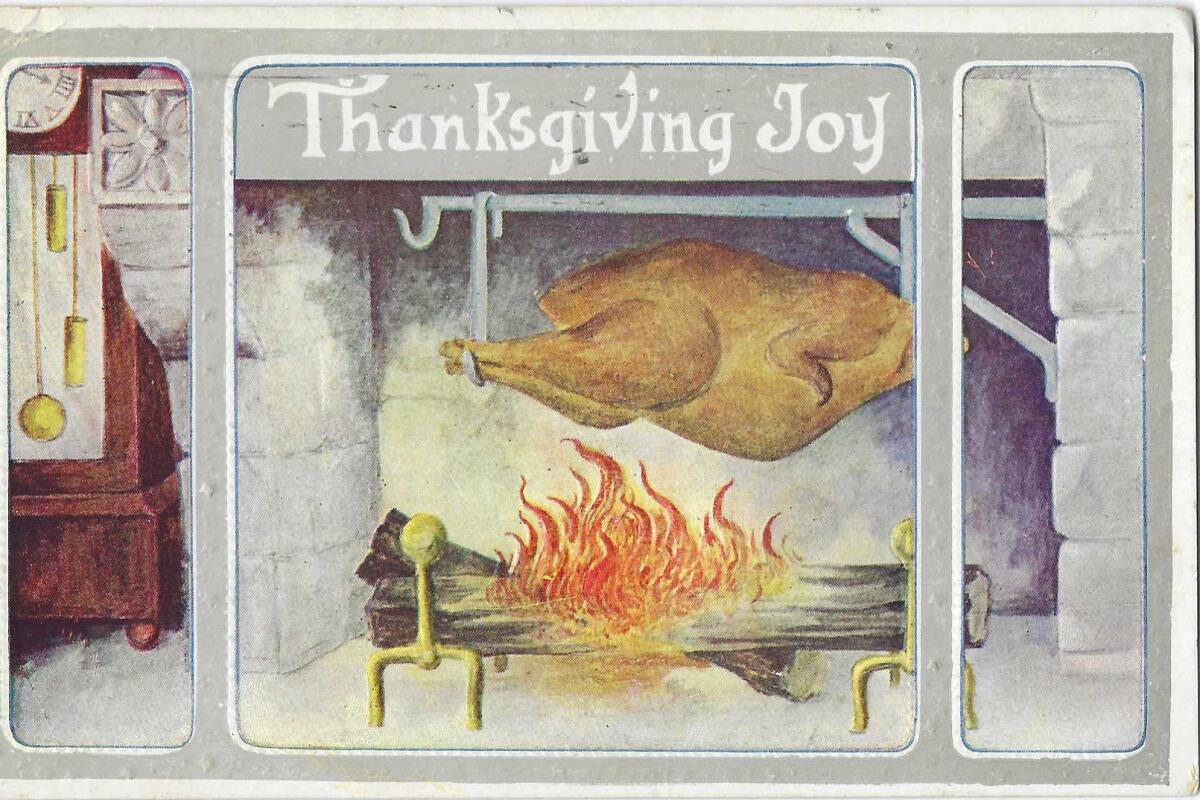

City Council candidate Ysabel Jurado cuts a cake at an event in Little Tokyo celebrating her campaign’s success in the March 5 primary election.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

“We can no longer follow the same playbook around budgeting, where we fully fund law enforcement and not the things that are proven to be effective in creating community safety,” he said.

Burgos, who is running to represent an east San Fernando Valley district, said she’s hoping that if she and Jurado win, other council members will be inclined to embrace more progressive policies.

“Right now, some people are afraid to make those choices,” said Burgos, an optician who lives in North Hollywood and part owner of an interactive murder mystery theater company.

Burgos, 45, and Jurado, 34, have a long list of shared policy goals. Both want to repeal Municipal Code 41.18, which prohibits homeless encampments next to schools, daycare centers and “sensitive” locations such as senior centers and freeway overpasses. Both want to create “social housing,” assigning city agencies to buy, fix and manage low-cost apartment complexes.

The two candidates want to shift traffic enforcement out of the LAPD. And they’re hoping to make bus and train fares free — a more complicated goal, since the decision rests not with the council but Metro’s 13-member board.

“We have a real opportunity to usher in a progressive era” at the City Council, “instead of just chipping away at some the solutions that we care about,” said Jurado, who finished first in an eight-way race for the Eastside seat now held by Councilmember Kevin de León.

Burgos, who describes herself as a leftist, finished second in the race to replace Council President Paul Krekorian, who is stepping down at the end of the year. In first place is former State Assemblymember Adrin Nazarian, a onetime Krekorian aide who describes himself as a “pragmatic progressive.”

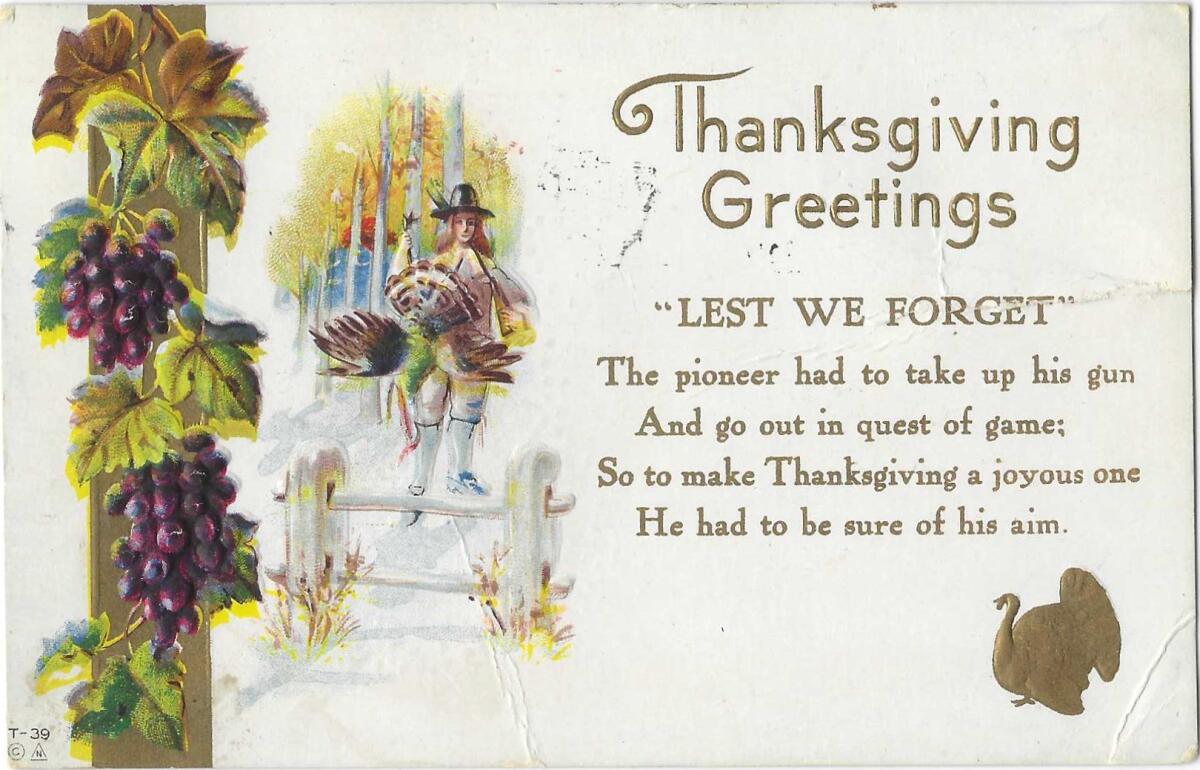

Los Angeles City Council Candidate Adrin Nazarian, grabbing campaign signs in North Hollywood earlier this year, is touting his own progressive credentials.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

Nazarian secured 37% of the vote in the primary, compared with 22% for Burgos. In an interview, he said that he, too, has pushed for progressive policies, such as expanded public transit, increased funding to help students pay for college and the creation of a single-payer healthcare system. In 2016 and again in 2020, Nazarian endorsed Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) for president in the Democratic primary.

“Judge me by my record. Judge me by my work ethic. There’s a reason why, in a crowded field of seven people, that I was able to garner almost 40% of the vote,” he said.

Nazarian, unlike Burgos, supports the continued use of 41.18. He also spoke in favor of Mayor Karen Bass’ push to hire more police and raise their pay.

Burgos, asked about those two issues, called for more alternatives to police, saying in a statement that “data has shown that there is no correlation between the number of sworn officers or the police budget and crime.”

De León, who came in second behind Jurado, also defended his progressive credentials, pointing to his work on immigrant rights, climate change and laws to prevent the displacement of renters in downtown, Boyle Heights and elsewhere.

“My record of taking on the toughest fights — Sanctuary State, 100% clean renewable energy, tenant protections — and winning for my constituents shows I know how to actually accomplish progressive change,” said De León, a former president of the state Senate who is seeking a second term.

De León faces a tough second round. He is still dealing with the fallout from a scandal over his participation in a secretly recorded conversation that featured racist and derogatory remarks.

Like Nazarian, he supports the LAPD raises, the hiring of more police and the use of 41.18.

L.A.’s leftists made their first serious inroads at City Hall four years ago, helping to elect Raman, a member of Democratic Socialists of America, to the council. Labor unions and advocacy groups replicated that success in 2022, working to elect two more Democratic Socialists of America-backed candidates — activist Eunisses Hernandez and labor organizer Hugo Soto-Martínez — and ousting two incumbents.

Of the three, Raman has proved to be the most moderate. Like Nazarian, she sometimes refers to herself as a “pragmatic progressive.” At one point in the primary campaign, she declined to say whether the city needs more police officers. At another, she relied on former Councilmember Paul Koretz — who has drawn the ire of L.A.’s leftists — to vouch for her with the Los Angeles County Democratic Party.

Attorney Edgar Khalatian, who represents real estate developers at City Hall, said he considers Raman to be pro-business. Raman, whose district straddles the Hollywood Hills, has shown “a strong backbone” on the city’s efforts to build more housing, while also working to address the homelessness crisis, he said.

“The reason housing prices are as astronomical as they are is decades of elected officials not supporting the development of more housing,” said Khalatian, who chairs the board of the Central City Assn., a downtown-based business group. “She supports housing, and will take the political heat from people in her district when she supports that housing.”

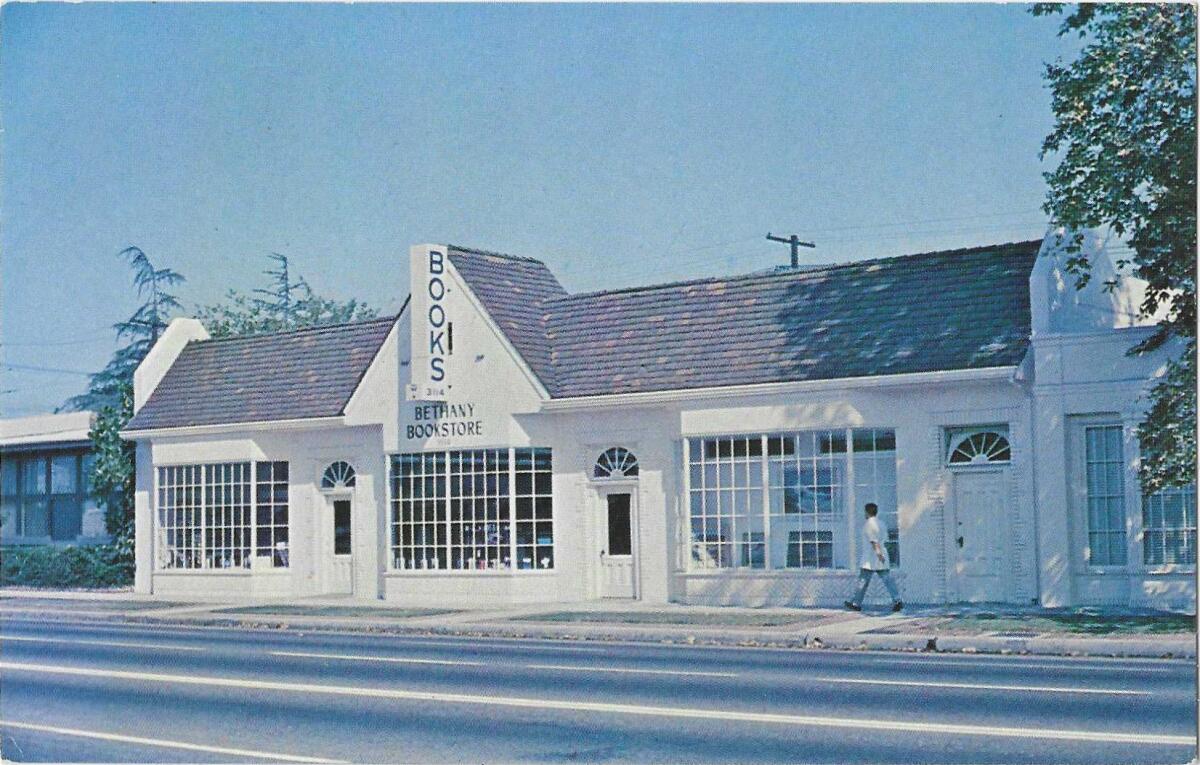

Los Angeles City Councilman Kevin de León, at his Eagle Rock office in September, is touting his work on climate change, immigrant rights and measures to prevent the displacement of renters.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Raman won despite more than $1.3 million in outside spending by the firefighters union, the police officers union, landlords and others for one of her opponents, Deputy City Atty. Ethan Weaver. Those groups waged a similar effort in the northwest Valley, spending a combined $1.1 million to help Lee turn back a challenge from nonprofit leader Serena Oberstein.

In South L.A.’s 10th Council District, law enforcement groups spent a combined $103,000 on ads portraying Reggie Jones-Sawyer, one of the five candidates, as soft on crime. Jones-Sawyer, a state assemblymember, came in fifth.

“For the rank-and-file of the league, we had a few goals” in this year’s city election, said Saggau, the police union spokesperson. “One of them was to ensure that Reggie Jones-Sawyer did not bring his brand of criminal justice reform, or ideas, to the city of L.A., and we succeeded on that.”

The 10th District will instead see a runoff between Councilmember Heather Hutt and attorney Grace Yoo, who share the same views on some of the city’s more contentious issues. Both support the city’s package of police raises and 41.18.

A spokesperson for the Democratic Socialists of America’s Los Angeles chapter said it’s unlikely her organization will get involved in that contest, in part because neither candidate is a DSA member. Given that they both favor the police raises, it would be “remarkably difficult” for either to win the DSA’s endorsement, said the spokesperson, who declined to give her full name.

David Zahniser

Source link