Kyiv, Ukraine – How often do you get a chance to witness the birth of a new world order? To chronicle not just a war – but a Darwinian fight for survival between a cunning little mammal and a cold-blooded, slow-thinking tyrannosaur?

To see how an entire nation unites to decolonise itself, to remake its identity and mindset, to stand up to a Goliath they once mistook for a “brother”?

There’s a price to pay for a ticket to an emotional roller coaster that will one day make your shrink rich.

You spend the war’s first days in bomb shelters, trying to sleep next to panicking women, weeping children and nervously smoking men.

You remember a tired, silent woman in her 70s who just hunches on a bench before somebody invites her to sit on their mattress, drink their tea and eat their biscuits.

You’ll never forget the kindness in the eyes and words of total strangers you met in the war’s first weeks.

You’ll also never forget the greedy cabbie who charges $600 to take you and your mother out of Kyiv to central Ukraine, a 260km-long (162-mile) ride that took almost 12 hours because of traffic jams and roadblocks.

Your mother is so unnerved that she loses sight in her right eye. After an urgent cataract surgery, for a month your life is all about applying five kinds of eye drops on time – because mum has dementia and can’t even remember that she’s 81.

These days, she doesn’t remember the war either and spends her days reading or watching movies made when she was young, when Russia and Ukraine were chained together into a Communist dystopia.

You sever ties with your lifelong friends and your own stepsister because they blindly believe Russian TV propaganda and never care to ask you about what’s happening in Ukraine.

When you hear the bang of an exploding cruise missile, you just pull down the curtains – because more people die of broken glass than of actual blasts.

You return to Kyiv weeks later to find the city of four million nearly empty. The air is clean, roads and streets filled with checkpoints and anti-tank “hedgehogs”.

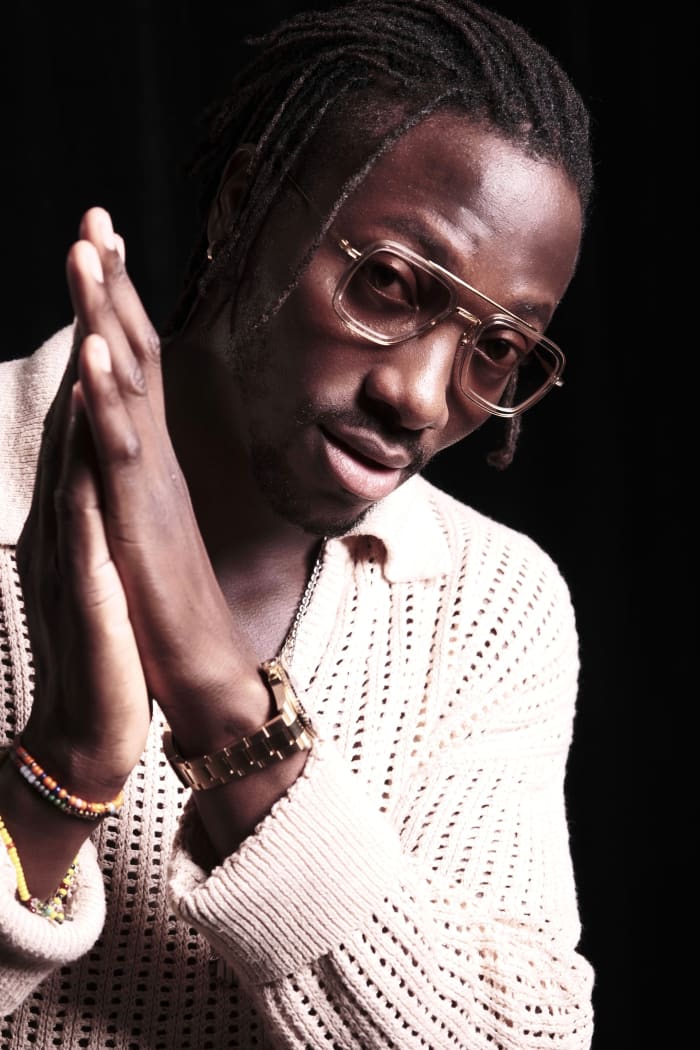

Banksy would later draw a picture next to one.

![Bansky art in Kyiv [Mansur Mirovalev]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/A-graffitti-by-Banksy-in-central-Kyiv.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C435)

You write about how Ukrainians ridicule Russia in memes and jokes, and realise that their ability to crack a joke even in their darkest hour, sometimes at their own expense is one of the key differences between Ukrainian and Russian mentalities.

When you manage to sleep in your apartment – the sound of explosions wakes you up.

Or was it just the wind shaking the windowpanes? An elderly neighbour in the apartment above yours?

When there is a real air raid, for the umpteenth time you recalculate the chances of cruise missiles or Iranian drones hitting your central neighbourhood and your apartment building hidden between a steep hill and another building.

The chances are minuscule. Statistically speaking, you are still much more likely to die in a car crash but your body still produces and pumps adrenaline.

You learn that the only healthy way to process the adrenaline is sit-ups and push-ups, dozens of them. Yeah, time to lose those kilograms gained after stress-eating at midnight.

And when the air raid is over and silence reverberates in your ears, you go out to examine the explosion craters. And you realise that three of them are on the way you used to take with your daughter to her elementary school.

Your daughter is not with you, that’s great and depressing at the same time, because she is safe – and because you are ready to gnaw off your right arm just for a chance to be with her.

She sends you a poorly-rhymed poem about the war or a drawing of a Ukrainian girl holding a gun next to a blue-and-yellow flag – and you feel like the proudest father on Earth.

Pride and empathy become your dominant feelings.

You are proud of being a tiny part of this Manichaean fight between absolute evil and nearly absolute good, of having a chance to describe how people around you turn into real-life heroes, mythical demigods.

You interview a human-rights activist-turned soldier and a month later, he is captured on the eastern front and faces years in jail as a “Ukrainian propagandist”.

You were about to interview another serviceman who wrote lyrics to a beautiful anti-war song but his truck gets blown to pieces by a landmine.

One more serviceman you’ve spoken to several times is back in the trenches, where he still finds time and web access to start a campaign to buy a $50,000 drone.

Then you learn that Ukrainians collected enough money to buy a satellite for their armed forces – and realise that to them, the sky is not the limit.

You talk to a man who survived weeks of bombing in Mariupol and he tells you from the safety of a hospital in western Ukraine that he might not survive surgery.

He does.

You talk to another Mariupol survivor, a woman with two small children, and when she repeats their question – “Mum, does it hurt to die?” – you start sobbing, and she calms you with a motherly, “It’s ok, it’s ok”.

You are fixated on Mariupol because that’s where pro-Russian rebels nearly killed you back in 2014, and only your loud cursing – “Guys, are you f—g crazy?” – stopped them from crushing your skull with metal rods.

Death or the possibility of death become part of almost every conversation.

A taxi driver tells you about his wife and daughter who went missing in Mariupol weeks ago.

A woman tells you how she drove out of her occupied village near Bucha and saw Russian soldiers shoot women and children in other cars.

You don’t believe her then and you feel guilty for it when you hear of the liberation of Bucha and the blood-curdling discovery of killed civilians a couple of weeks later.

You interview another man from Bucha, who says Russians had doused him with fuel to “set him on fire and send back to his people”, and realise that his words and their deeds cancel, annihilate the Russian culture you had grown up on.

And most Ukrainians around you don’t hesitate to cancel their own poets and writers, rename streets and city squares named after them and tear down their statues just because they wrote in Russian.

You talk to a serviceman who looks and talks like a small-time hoodlum, and when he tells you how he and his men armed with AK-47s and Molotov cocktails ambushed three dozen Russian APCs full of gun-toting Chechens, you realise that you’re looking at a character from an epic poem.

Of course, the main protagonist in this poem is President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s funniest man from a Russian-speaking Jewish family who once wanted to sign a truce with Putin.

Zelenskyy didn’t chicken out, he stayed in Kyiv, he is 10 feet tall and can kill a dozen Russians with just an angry glance.

(You are still mad at Zelenskyy’s press service for refusing an interview with him months before his 2019 election, when no Western news editor even heard his name, let alone believed in his chances of winning.)

Your hatred crystallises, becomes razor-sharp and pointed at the bad guy in the poem, the angry bald man in the Kremlin, only you don’t call him a person, a human any more.

You tell your daughter how you had seen Putin many times, years ago, in the Kremlin:

“He was so full of hatred, he just radiated it.”

And she tells you that she wants to have a superpower to teleport herself to the Kremlin and “hit him with a skillet”.

Death or the possibility of death are part of any conversation.

A staffer of the Chornobyl nuclear plant tells you how he’d spent weeks next to Russian occupiers. How they asked for vodka and he laced it with radioactive isotopes so that within hours they “barfed blood.” But he refuses to be interviewed, another entry in your list of great stories that would never be written.

A construction manager tells you that one of his employees, a single father, was drafted and his little son ended up in an orphanage.

You learn to take the stairs or walk on icy asphalt in total darkness because electricity is no longer wasted on street lights.

You get emotionally paralysed because your brain can’t process this much violence, tears and tragedy.

A single phrase or photo breaks you down, you sob and wail uncontrollably and can’t force yourself to finish the transcription of an interview.

You realise that you’re burned out.

But like Phoenix, a mythical bird that self-immolates only to be reborn from its own ashes, you wash your face, do some pushups and get back to work.