Why should fasts lasting longer than 24 hours and particularly for three or more days only be done under the supervision of a health professional and preferably in a live-in clinic?

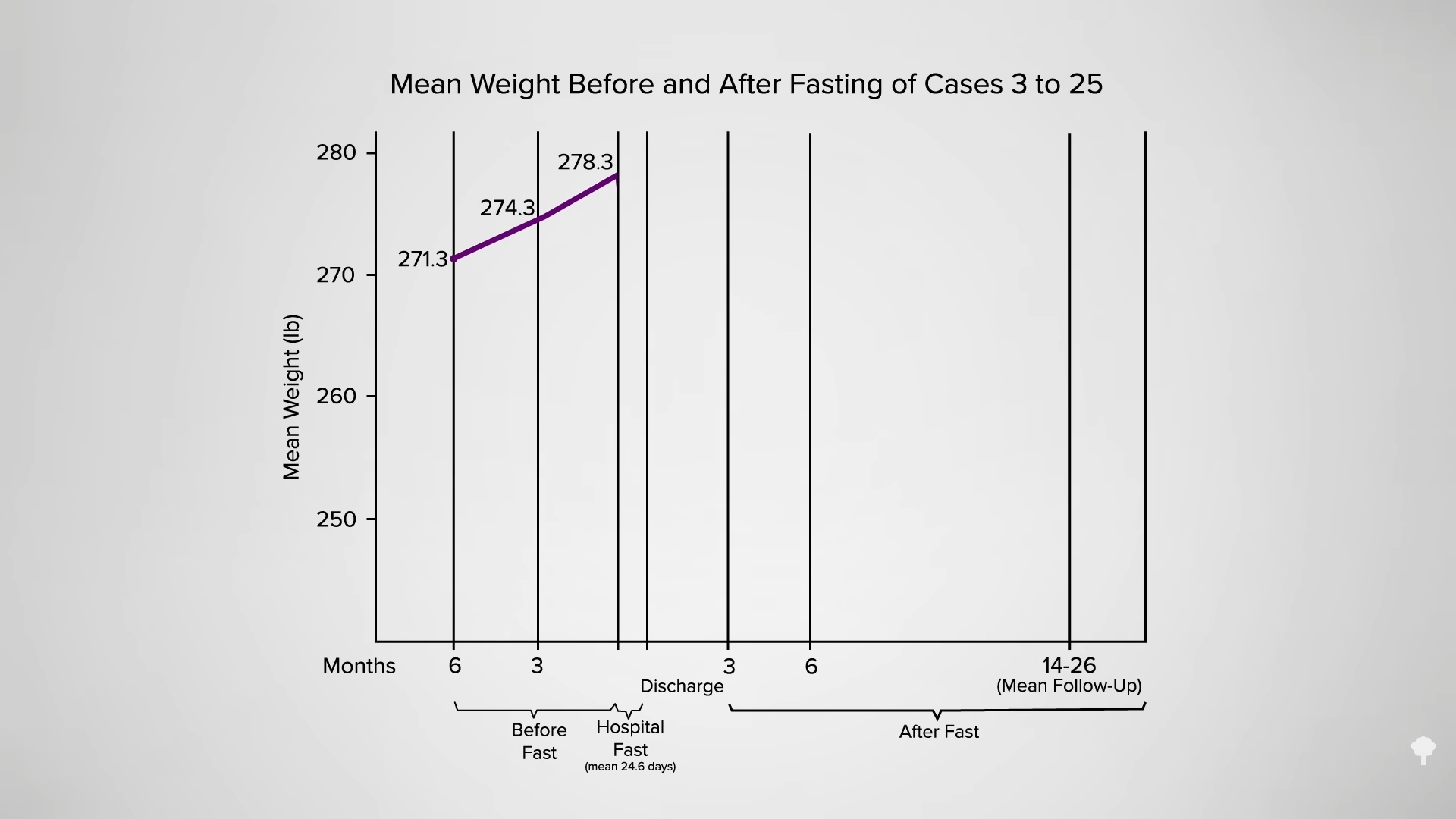

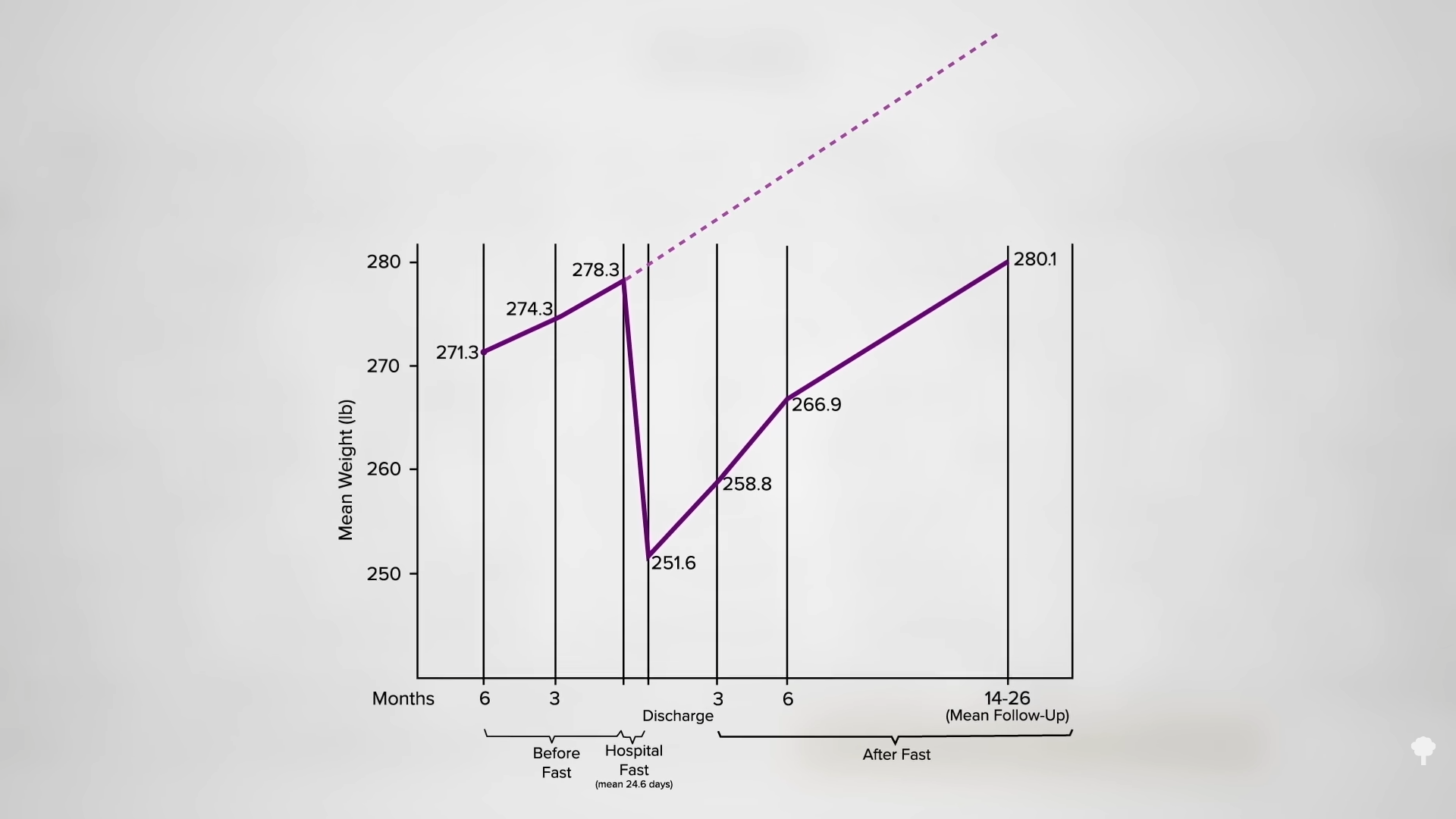

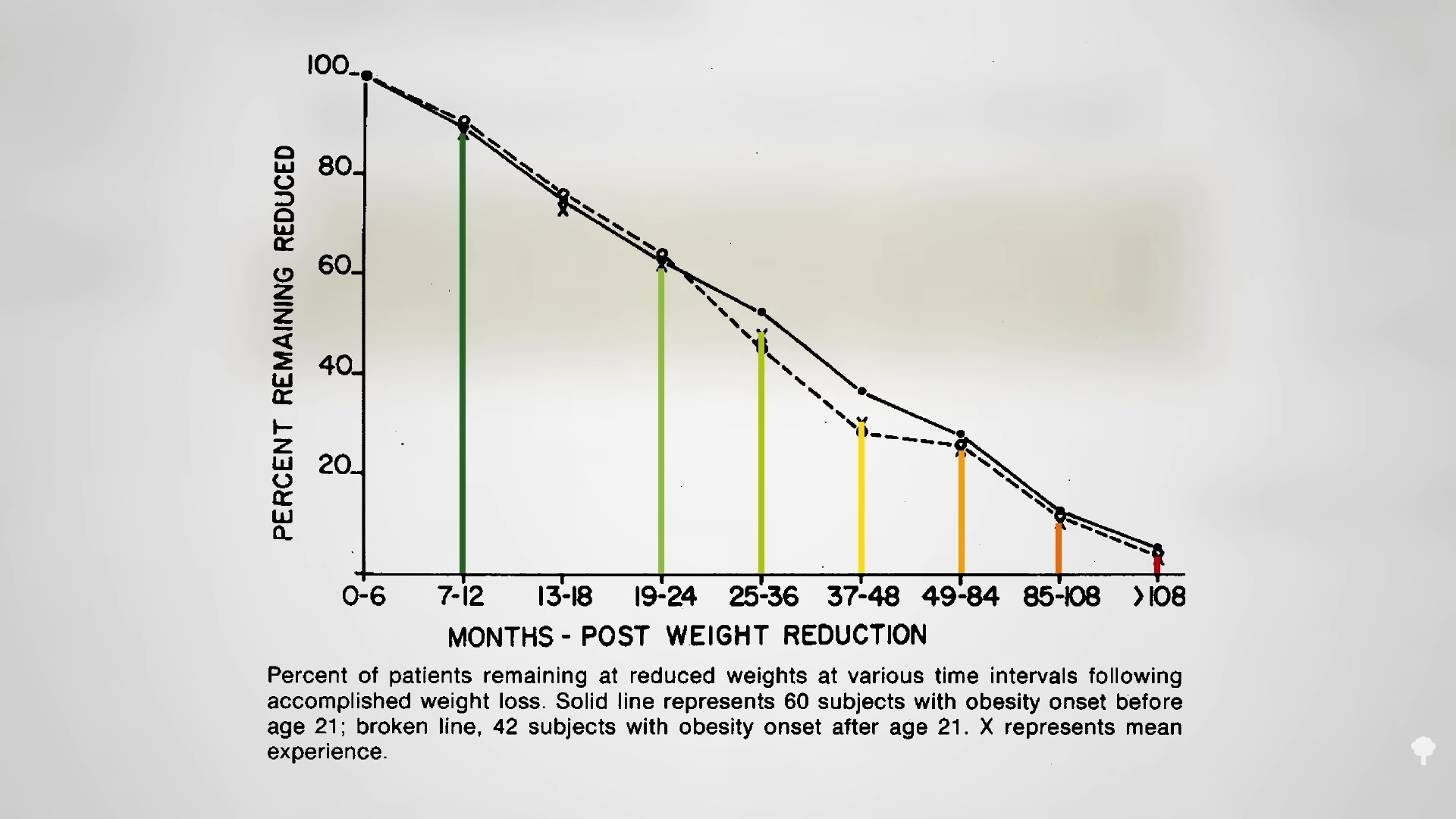

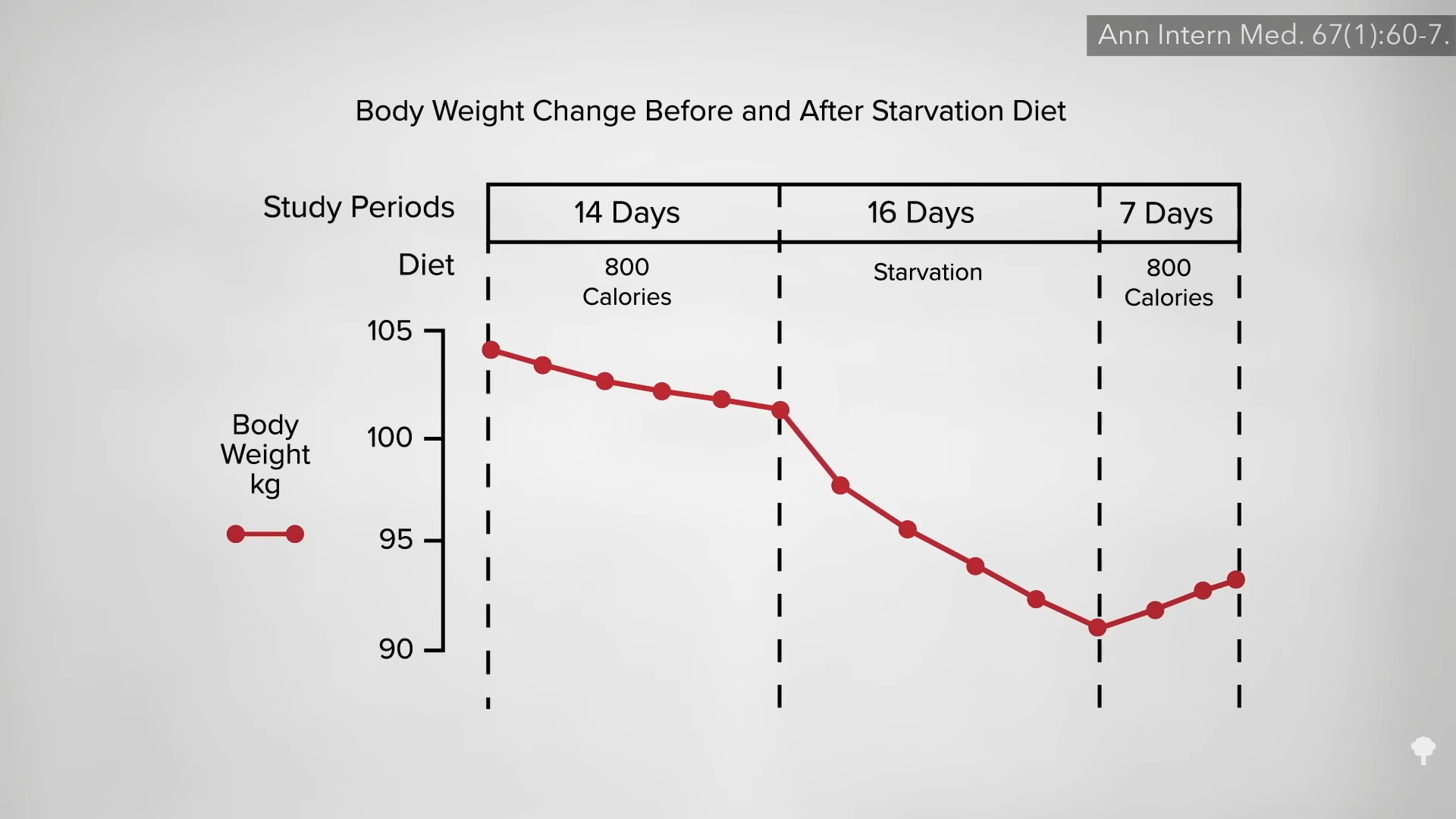

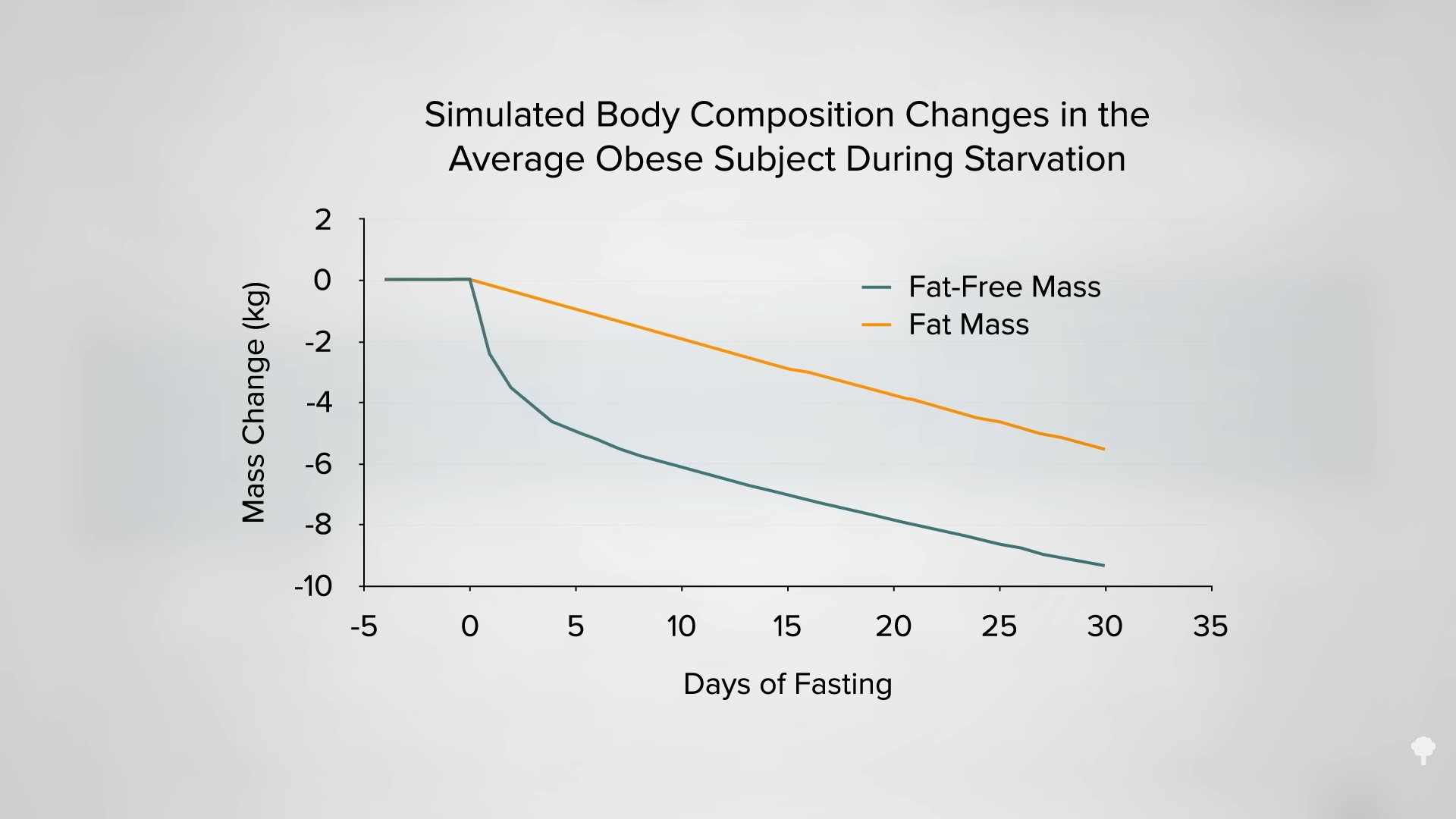

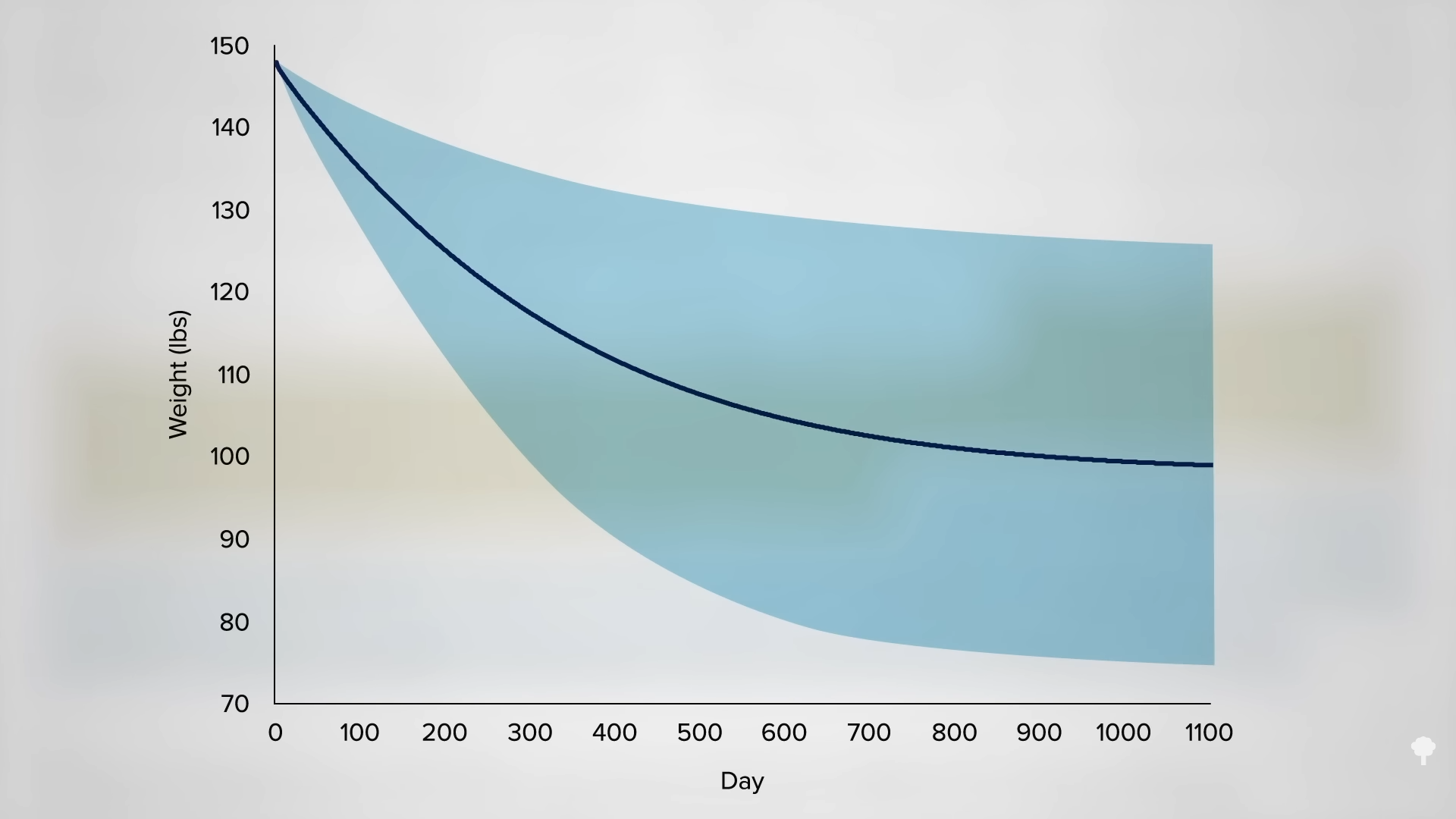

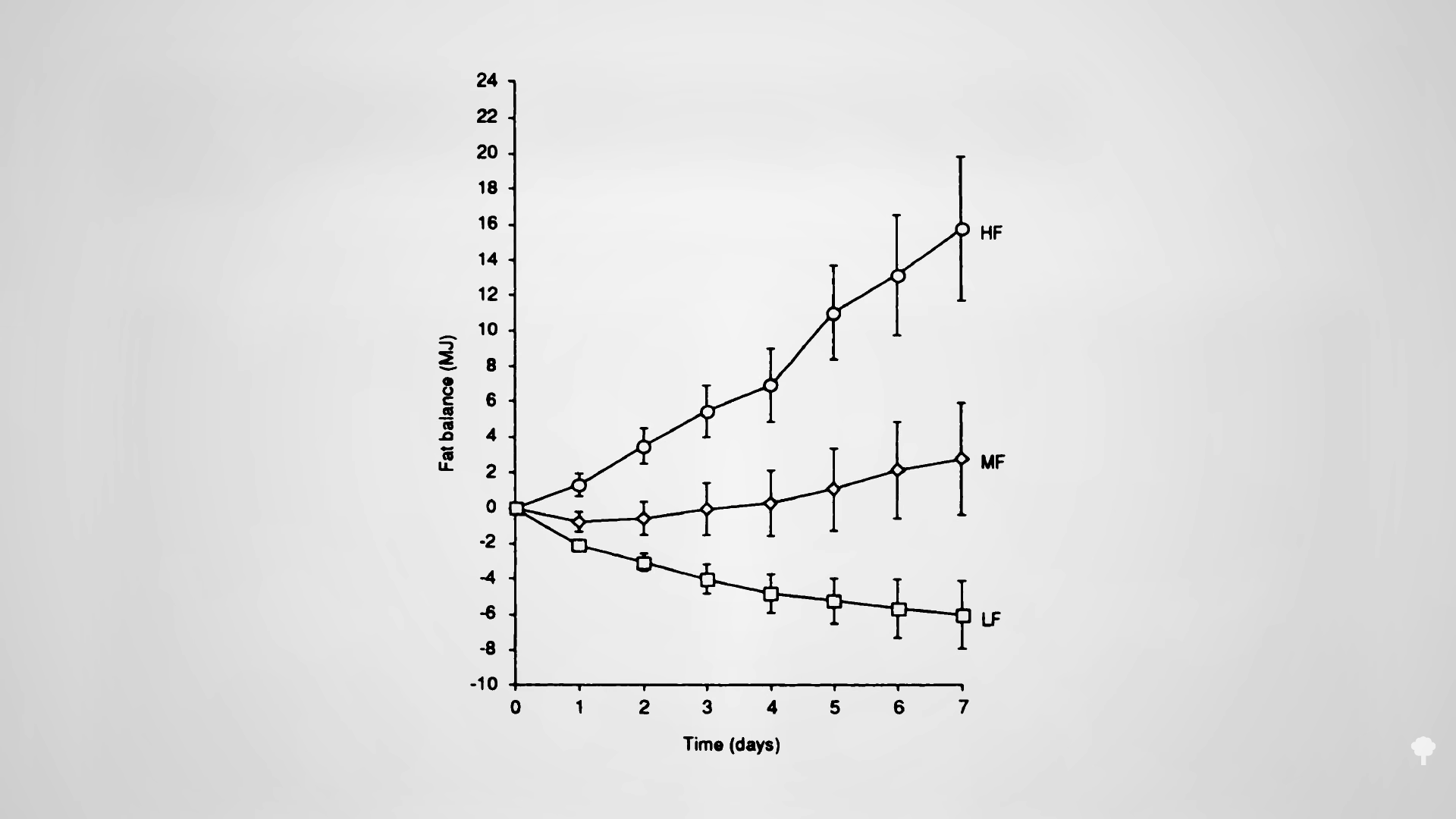

Fasting for a week or two can actually interfere with the loss of body fat, as shown at the start of my video Is Fasting for Weight Loss Safe?. But, eventually, after the third week of fasting, fat loss starts to overtake the loss of lean body mass in obese individuals, as seen in the graph below and at 0:14 in my video. Is it safe to go that long without food?

Proponents speak of fasting as a cleansing process, but some of what is being purged from our bodies are essential vitamins and minerals. People who are heavy enough can fast up to 382 days without calories, but no one can go even a fraction of that long without vitamins. Scurvy, for example, can be diagnosed within as few as four weeks without any vitamin C. Beriberi, deficiency of thiamine (vitamin B1), may start even earlier in fasting patients. And, once it manifests, it can result in brain damage within days, which can eventually become irreversible.

Even though fasting patients report problems such as nausea and indigestion after taking supplements, all of the months-long fasting cases I’ve discussed previously were given daily multivitamins and mineral supplementation as necessary. Without supplementation, hunger strikers and those undergoing prolonged fasts for therapeutic or religious purposes (like the Baptist pastor hoping “to enhance his spiritual powers for exorcism”) have ended up paralyzed, become comatose, or worse.

Nutrient deficiencies aren’t the only risk. After reading about all of the successful reports of massive weight loss from prolonged fasting in the medical literature, one doctor decided to give it a try with his patients. Of the first dozen he tried it on, two died. In retrospect, the two patients who died had started out with heart failure and had been on diuretics. Fasting itself produces pronounced diuresis, meaning loss of water and electrolytes through the urine, so it was the combination of fasting on top of the water pills that likely depleted their potassium and triggered their fatal heart rhythms. The doctor went out of his way to point out that both of the people who died started out “in severe heart failure, complicated by gross obesity; but both had improved greatly whilst undergoing starvation therapy.” That seems like a small consolation since they were both dead within a matter of weeks.

Not all therapeutic fasting fatalities were complicated by concurrent medication use, though. One researcher writes: “At first he did very well and experienced the usual euphoria…His pulse, blood pressure, and electrolytes remained satisfactory, but in the middle of the third week of treatment, he suddenly collapsed and died. This line of treatment is certainly tempting because it does produce weight loss and the patient feels so much better, but the report of case-fatalities”—the whole part about killing people—“must make it a very suspect line of management.”

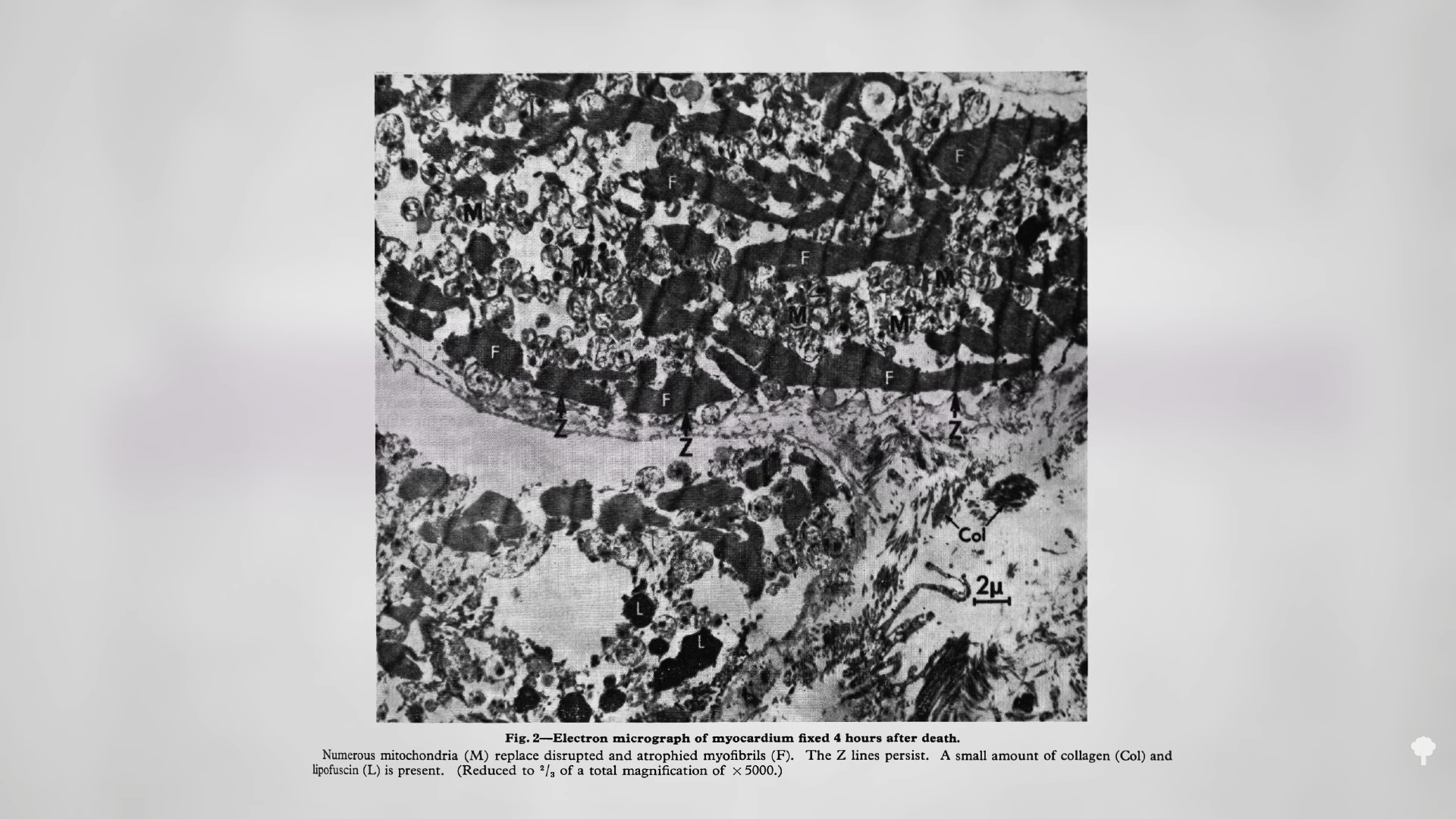

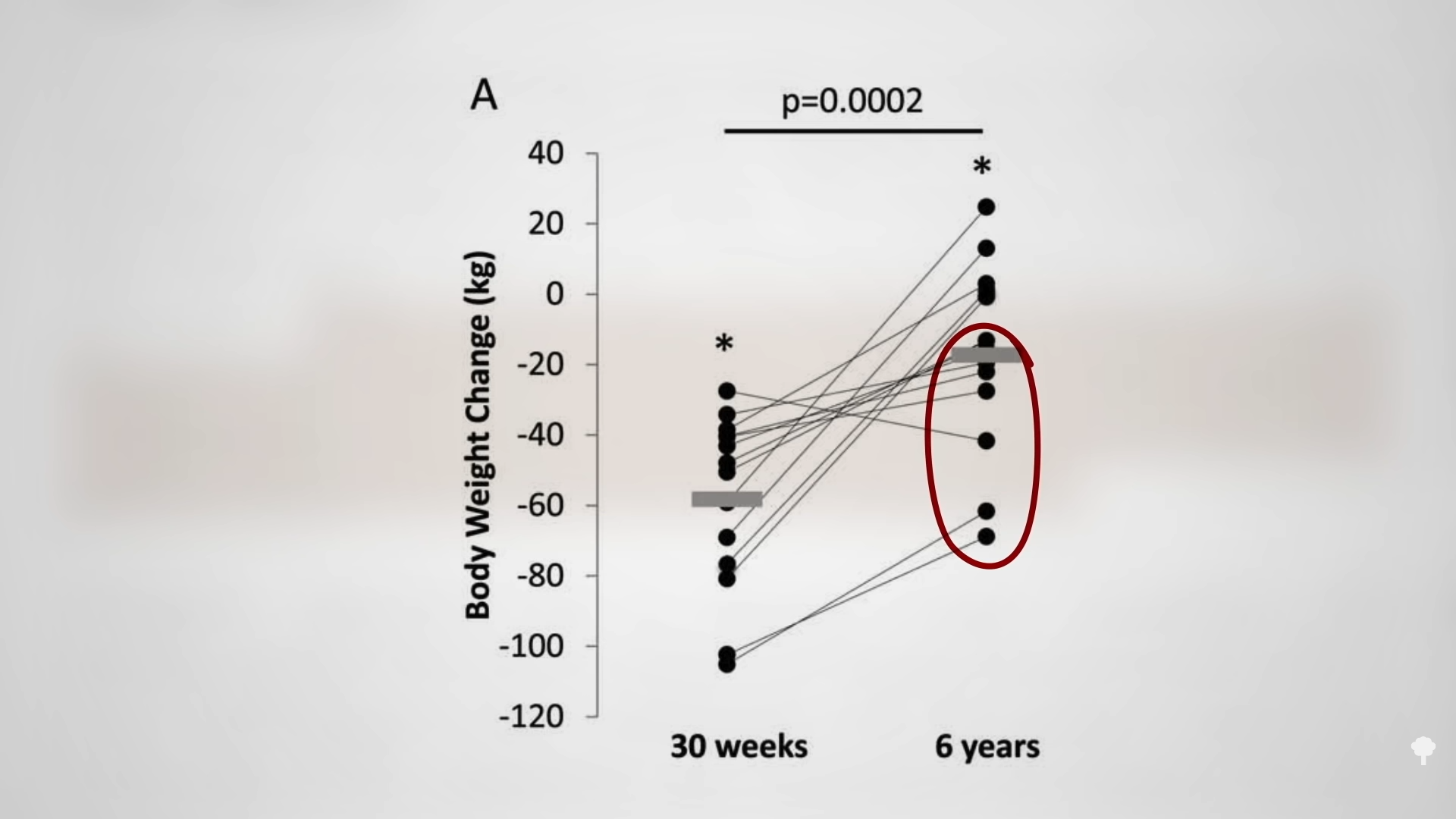

Contrary to the popular notion that the heart muscle is specially spared during fasting, the heart appears to experience similar muscle wasting. This was “described in the victims of the Warsaw ghetto” during World War II in a remarkable series of detailed studies carried out by the ghetto physicians before they themselves succumbed. In a case entitled “Gross Fragmentation of Cardiac Fiber After Therapeutic Starvation for Obesity,” a 20-year-old woman successfully “achieved her ideal weight” after losing 128 pounds by fasting for 30 weeks. “After a breakfast of one egg,” she had a heart attack and died. On autopsy, as you can see below and at 3:44 in my video, the muscle fibers in her heart showed evidence of widespread disintegration. The pathologists suggested that fasting regimens “should no longer be recommended as a safe means of weight reduction.”  Breaking the fast appears to be the most dangerous part. After World War II, as many as one out of five starved Japanese prisoners of war tragically died following liberation. Now known as “refeeding syndrome,” multiorgan system failure can result from resuming a regular diet too quickly. This is because there are critical nutrients such as thiamine and phosphorus that are used to metabolize food. Therefore, in the critical refeeding window, if too much food is taken before these nutrients can be replenished, demand may exceed supply. Whatever residual stores you still carry can be driven down even further, with potentially fatal consequences. This is why rescue workers are taught to always give thiamine before food to victims who have been trapped or otherwise unable to eat. Thiamine is responsible for the yellow color of “banana bags,” a term you might have heard used in medical dramas to describe an IV fluid concoction often given to malnourished alcoholics to prevent a similar reaction. (You can see a photo of them below and at 4:53 in my video.) Anyone “with negligible food intake for more than five days” may be at risk of developing refeeding problems.

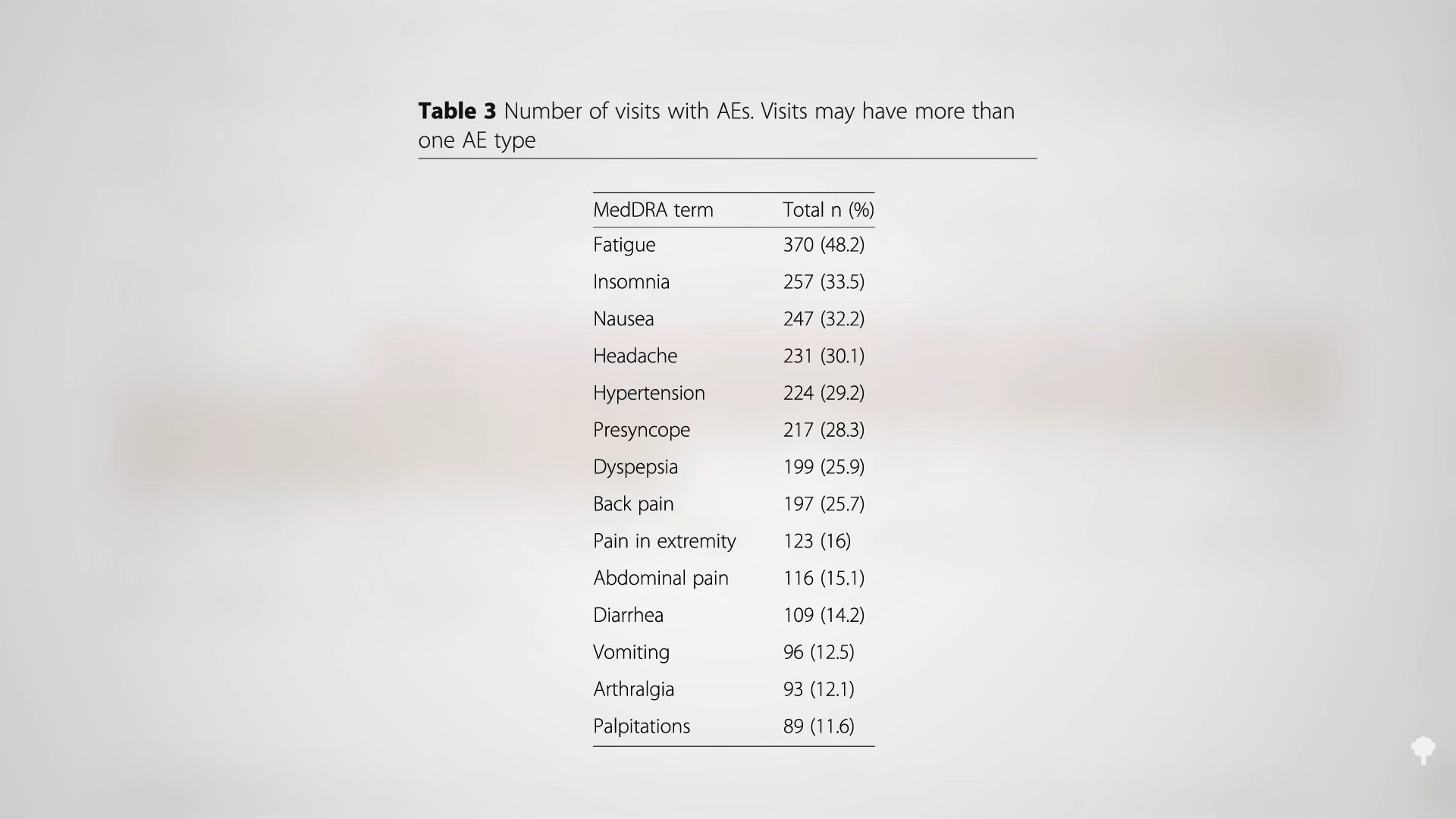

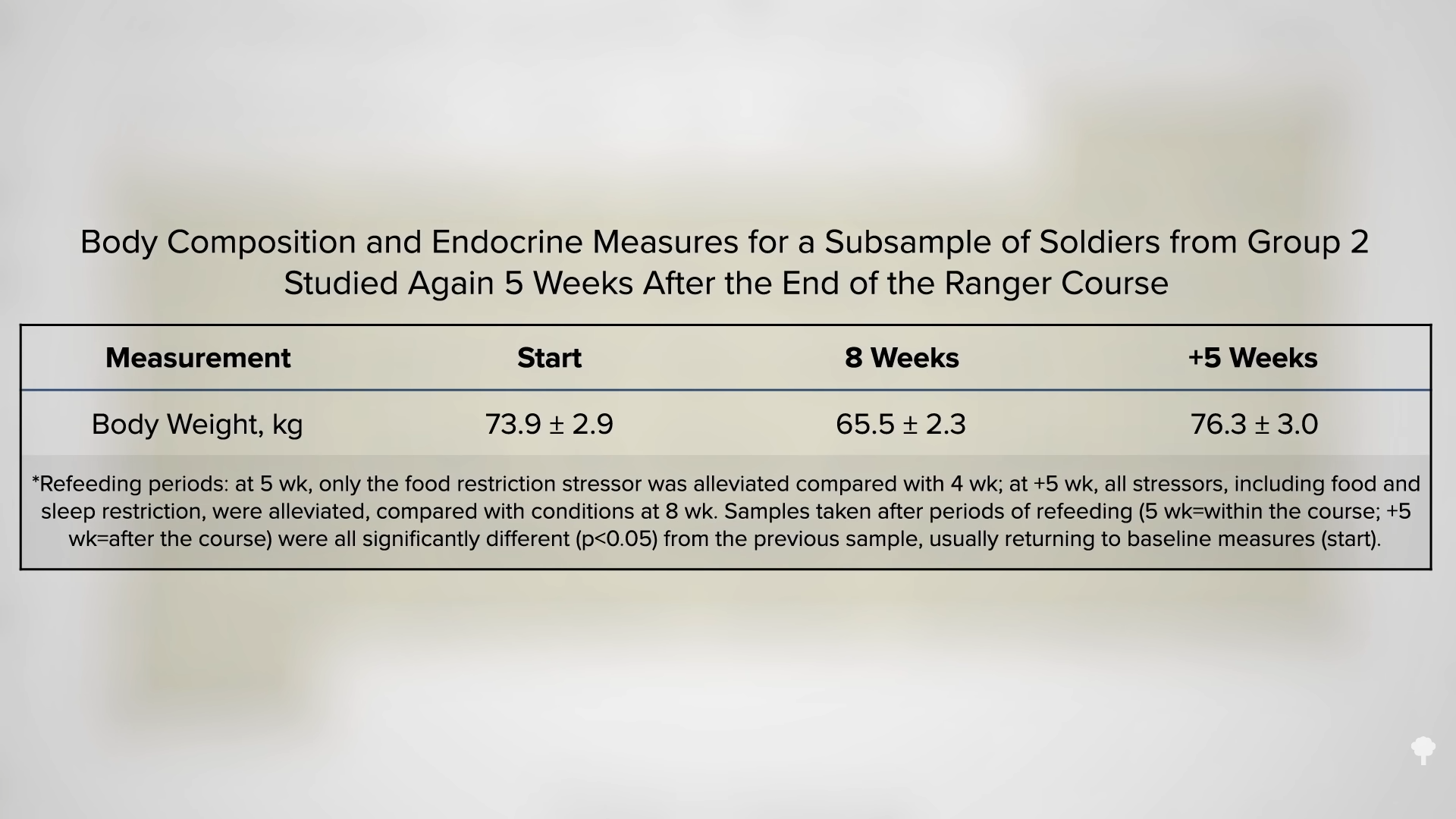

Breaking the fast appears to be the most dangerous part. After World War II, as many as one out of five starved Japanese prisoners of war tragically died following liberation. Now known as “refeeding syndrome,” multiorgan system failure can result from resuming a regular diet too quickly. This is because there are critical nutrients such as thiamine and phosphorus that are used to metabolize food. Therefore, in the critical refeeding window, if too much food is taken before these nutrients can be replenished, demand may exceed supply. Whatever residual stores you still carry can be driven down even further, with potentially fatal consequences. This is why rescue workers are taught to always give thiamine before food to victims who have been trapped or otherwise unable to eat. Thiamine is responsible for the yellow color of “banana bags,” a term you might have heard used in medical dramas to describe an IV fluid concoction often given to malnourished alcoholics to prevent a similar reaction. (You can see a photo of them below and at 4:53 in my video.) Anyone “with negligible food intake for more than five days” may be at risk of developing refeeding problems.  Medically-supervised fasting has gotten much safer now that there are proper refeeding protocols. We now know what warning signs to look for and who shouldn’t be fasting in the first place, such as those who have advanced liver or kidney failure, porphyria, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, and pregnant and breastfeeding women. The most comprehensive safety analysis of medically supervised, water-only fasting was recently published by the TrueNorth Health Center in California. Out of 768 visits to its facility for fasts up to 41 days, were there any adverse events? There were 5,961 of them! Most of these were mild, known reactions to fasting, such as fatigue, nausea, insomnia, headache, dizziness, upset stomach, and back pain. Only two serious events were reported, and no fatalities. You can see the chart below and at 5:58 in my video.

Medically-supervised fasting has gotten much safer now that there are proper refeeding protocols. We now know what warning signs to look for and who shouldn’t be fasting in the first place, such as those who have advanced liver or kidney failure, porphyria, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, and pregnant and breastfeeding women. The most comprehensive safety analysis of medically supervised, water-only fasting was recently published by the TrueNorth Health Center in California. Out of 768 visits to its facility for fasts up to 41 days, were there any adverse events? There were 5,961 of them! Most of these were mild, known reactions to fasting, such as fatigue, nausea, insomnia, headache, dizziness, upset stomach, and back pain. Only two serious events were reported, and no fatalities. You can see the chart below and at 5:58 in my video.  “Fasting periods lasting longer than 24 hr, and particularly those lasting 3 or more days, should be done under the supervision of a physician and preferably in a [live-in] clinic.” In other words, don’t try this at home! This is not just legalistic mumbo-jumbo. For example, normally, your kidneys dive into sodium conservation mode during fasting, but should that response break down, you could rapidly develop an electrolyte abnormality that may only manifest with non-specific symptoms, like fatigue or dizziness, which could easily be dismissed until it’s too late.

“Fasting periods lasting longer than 24 hr, and particularly those lasting 3 or more days, should be done under the supervision of a physician and preferably in a [live-in] clinic.” In other words, don’t try this at home! This is not just legalistic mumbo-jumbo. For example, normally, your kidneys dive into sodium conservation mode during fasting, but should that response break down, you could rapidly develop an electrolyte abnormality that may only manifest with non-specific symptoms, like fatigue or dizziness, which could easily be dismissed until it’s too late.

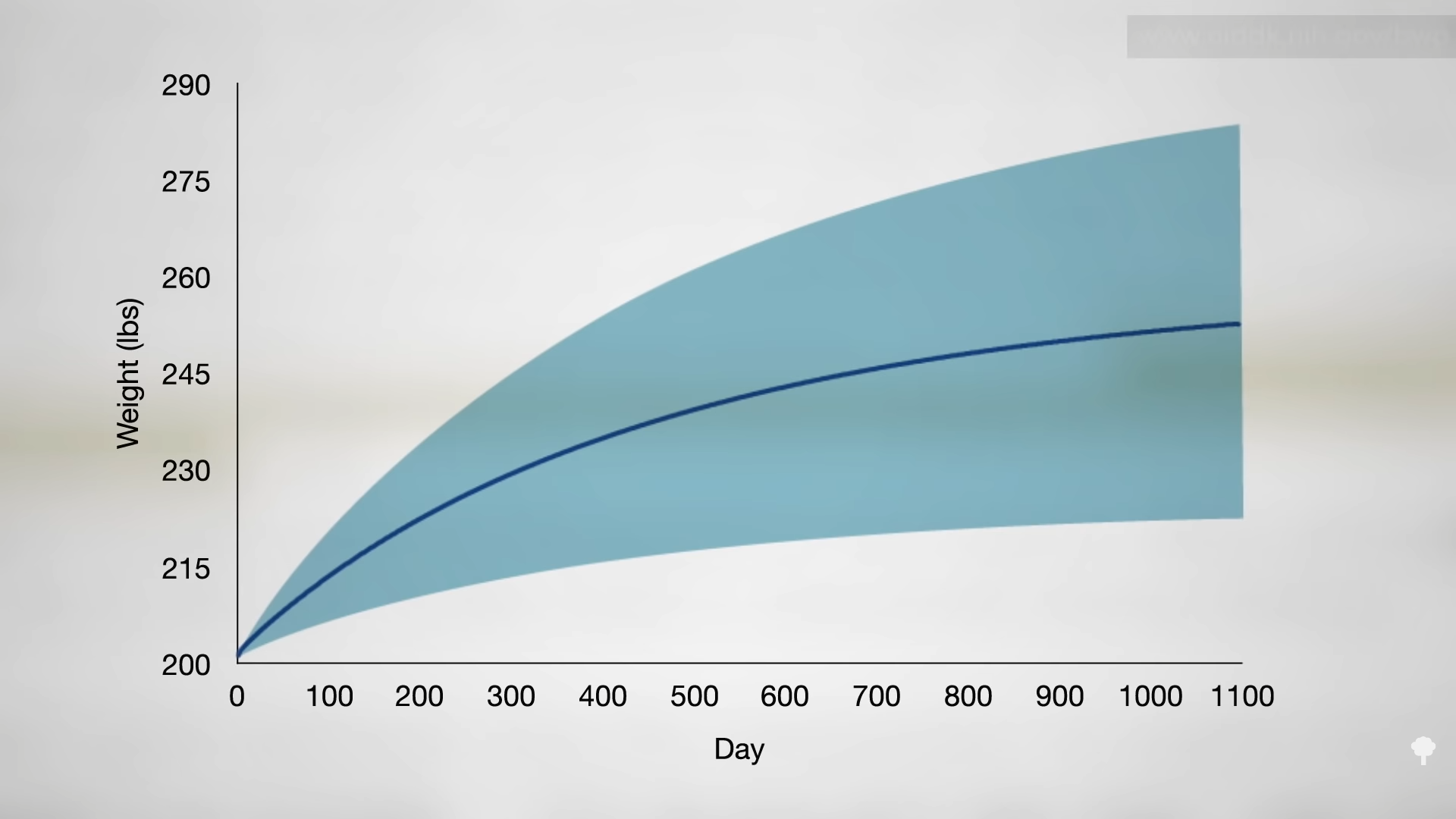

The risks of any therapy must be premised on the severity of the disease. The consequences of obesity are considered so serious that effective therapies could have “considerable acceptable toxicity.” For example, many consider major surgery for obesity to be a justifiable risk, but the keyword is effective.

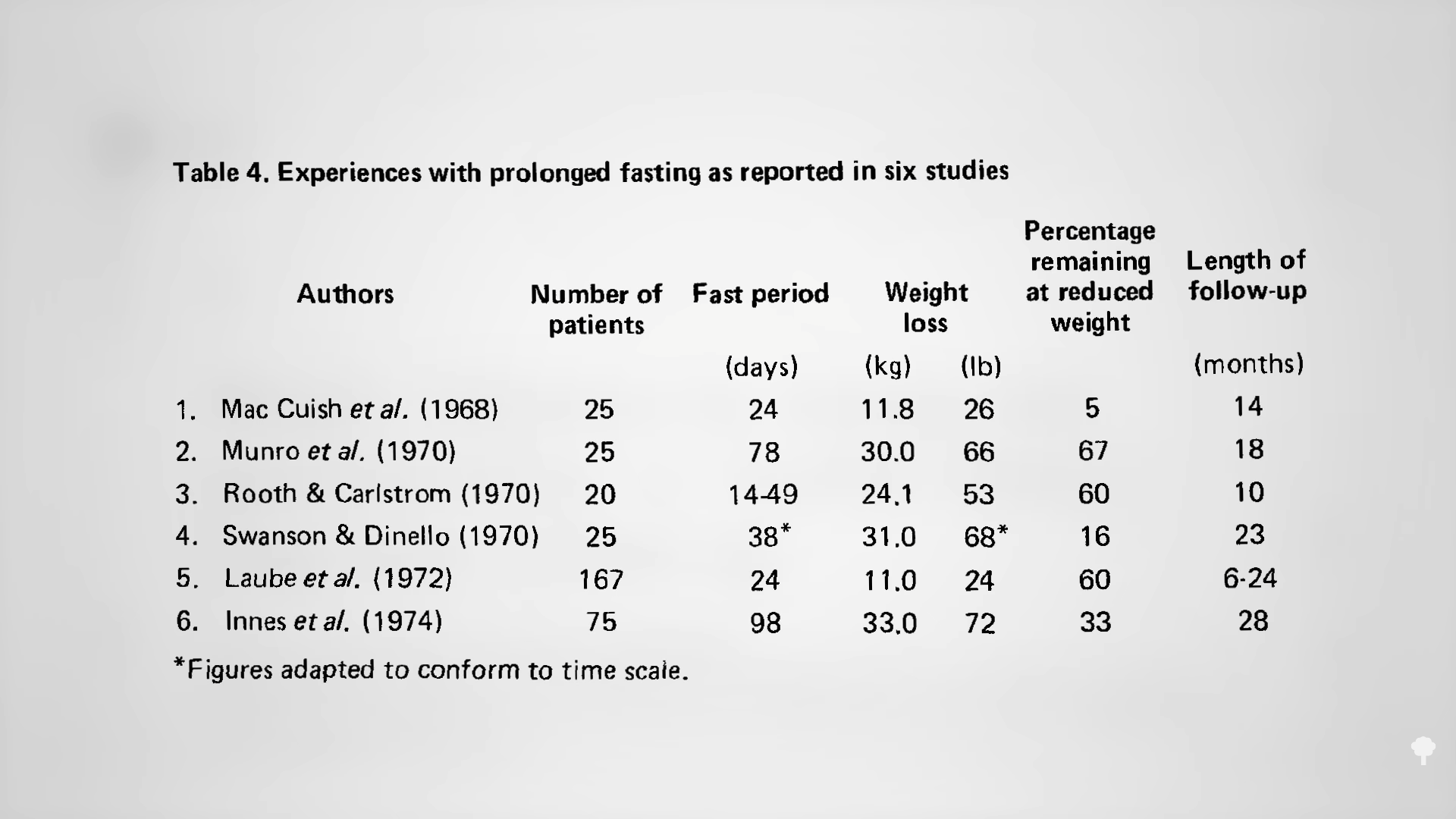

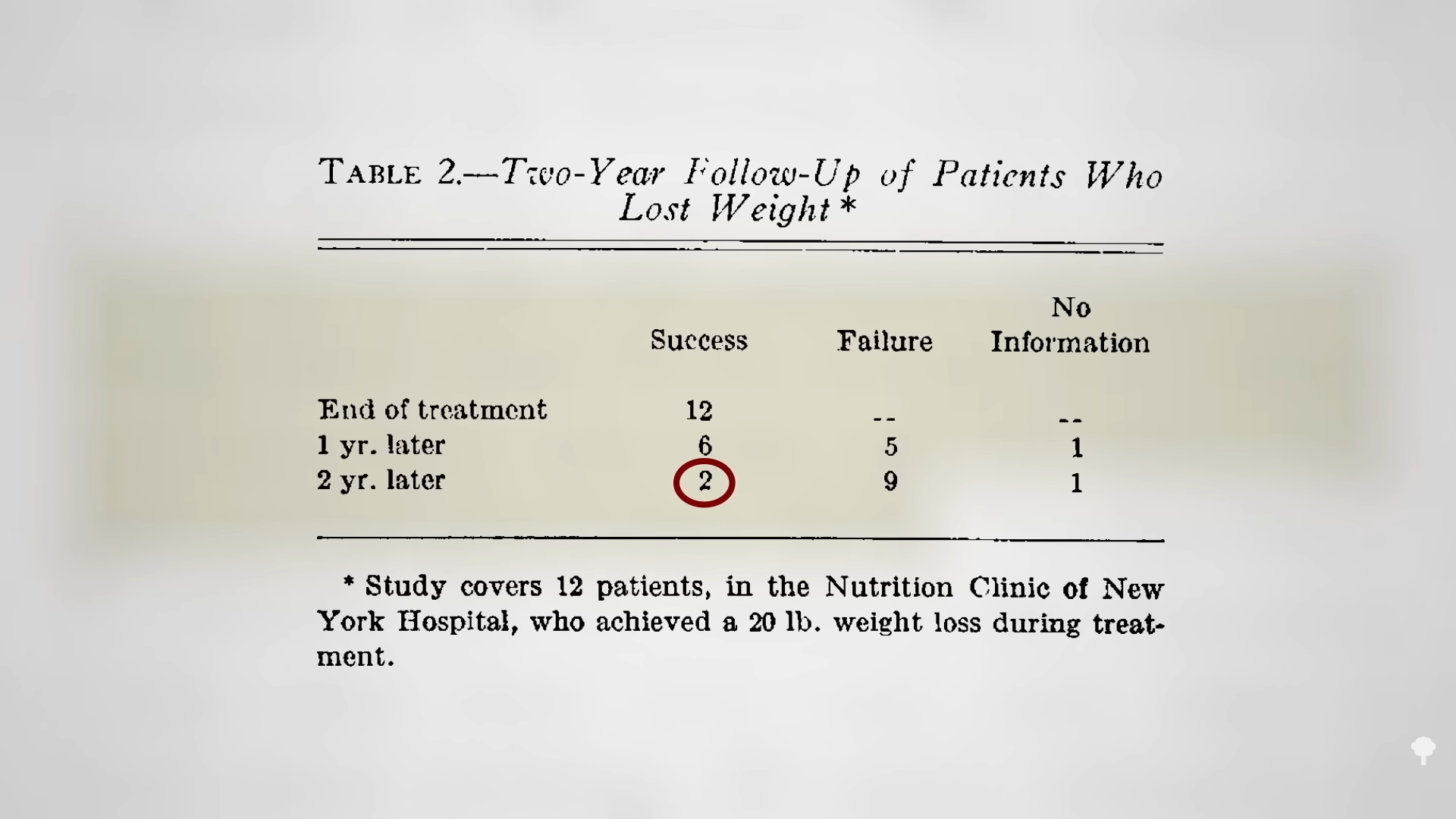

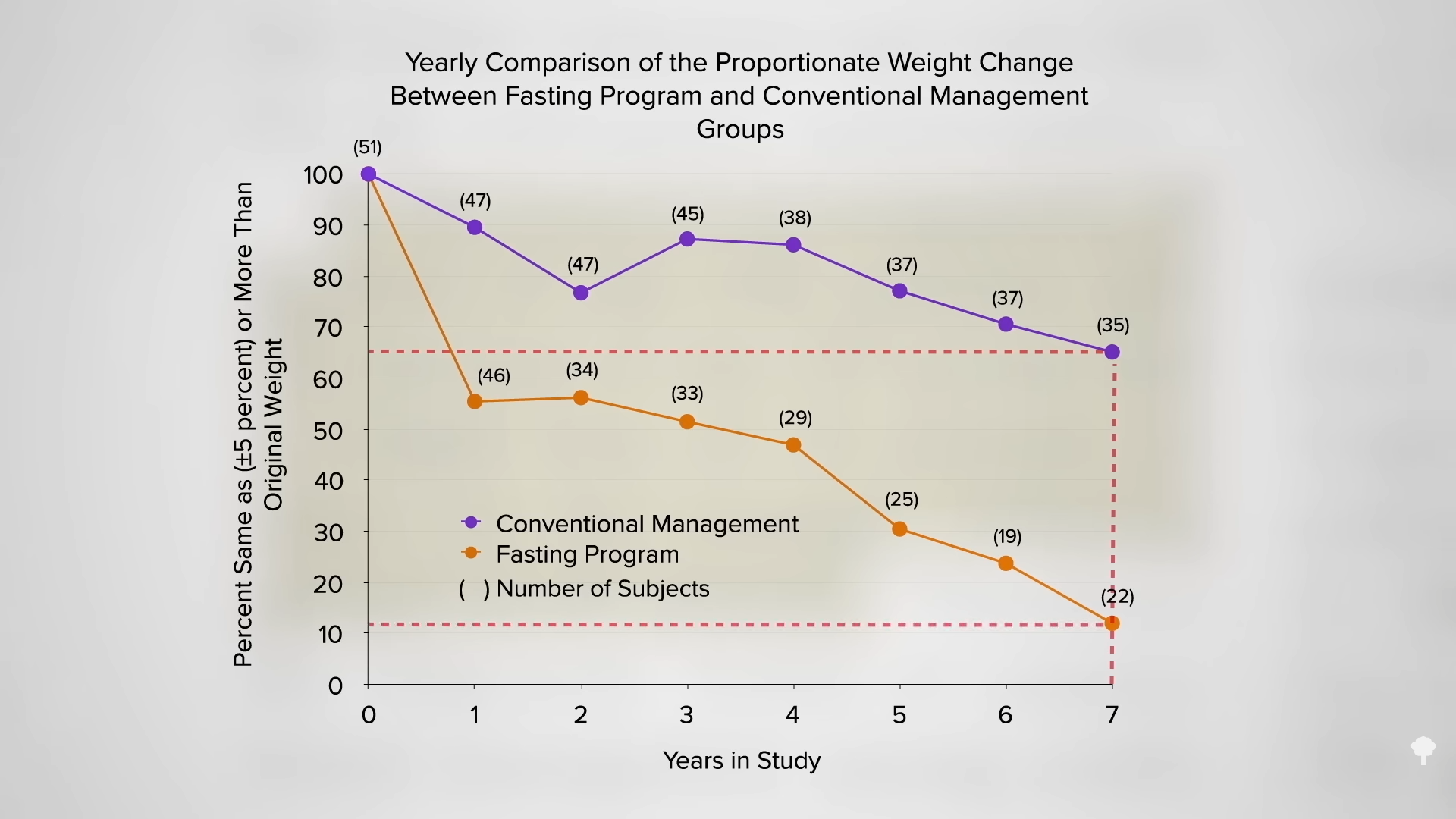

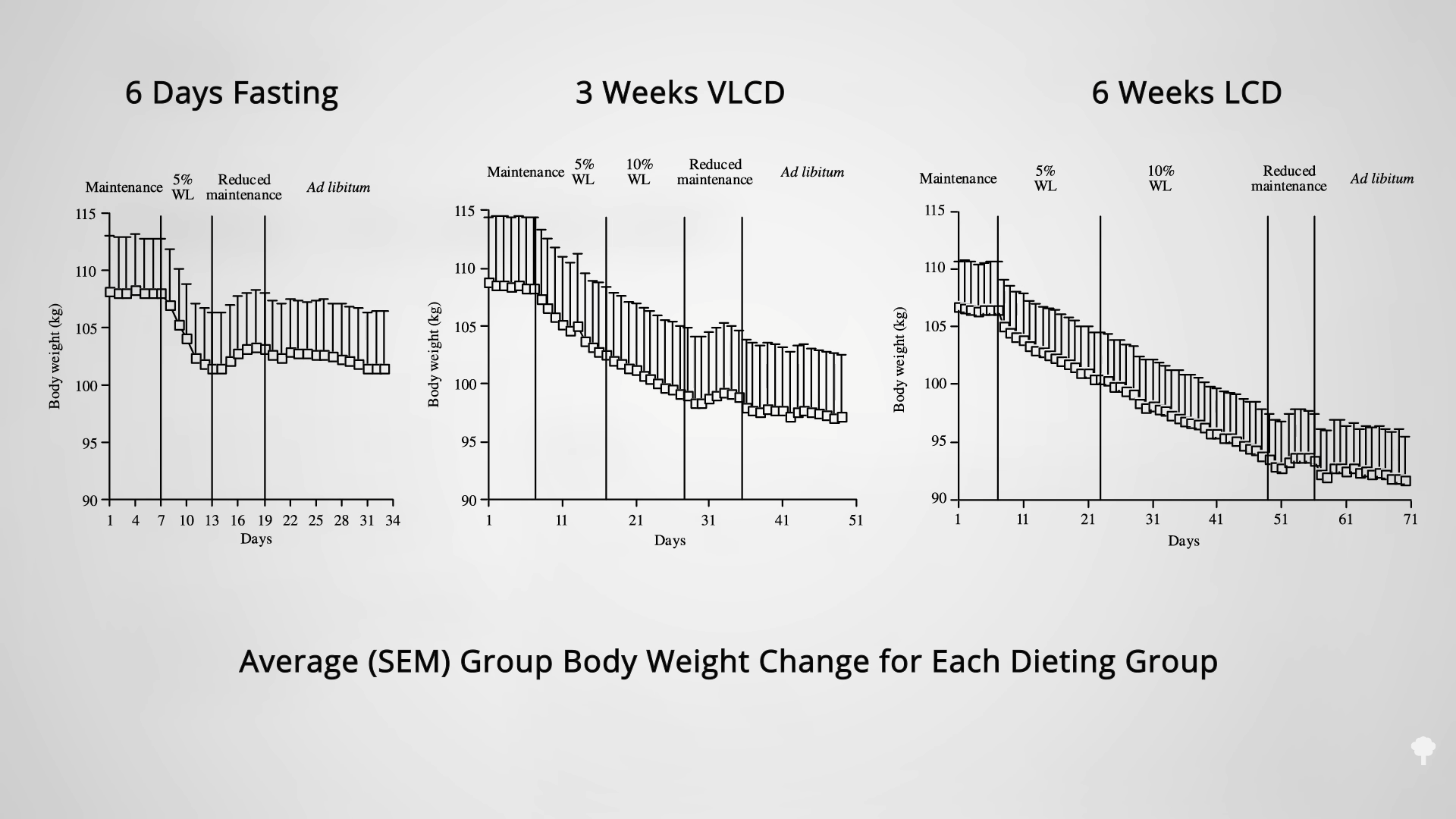

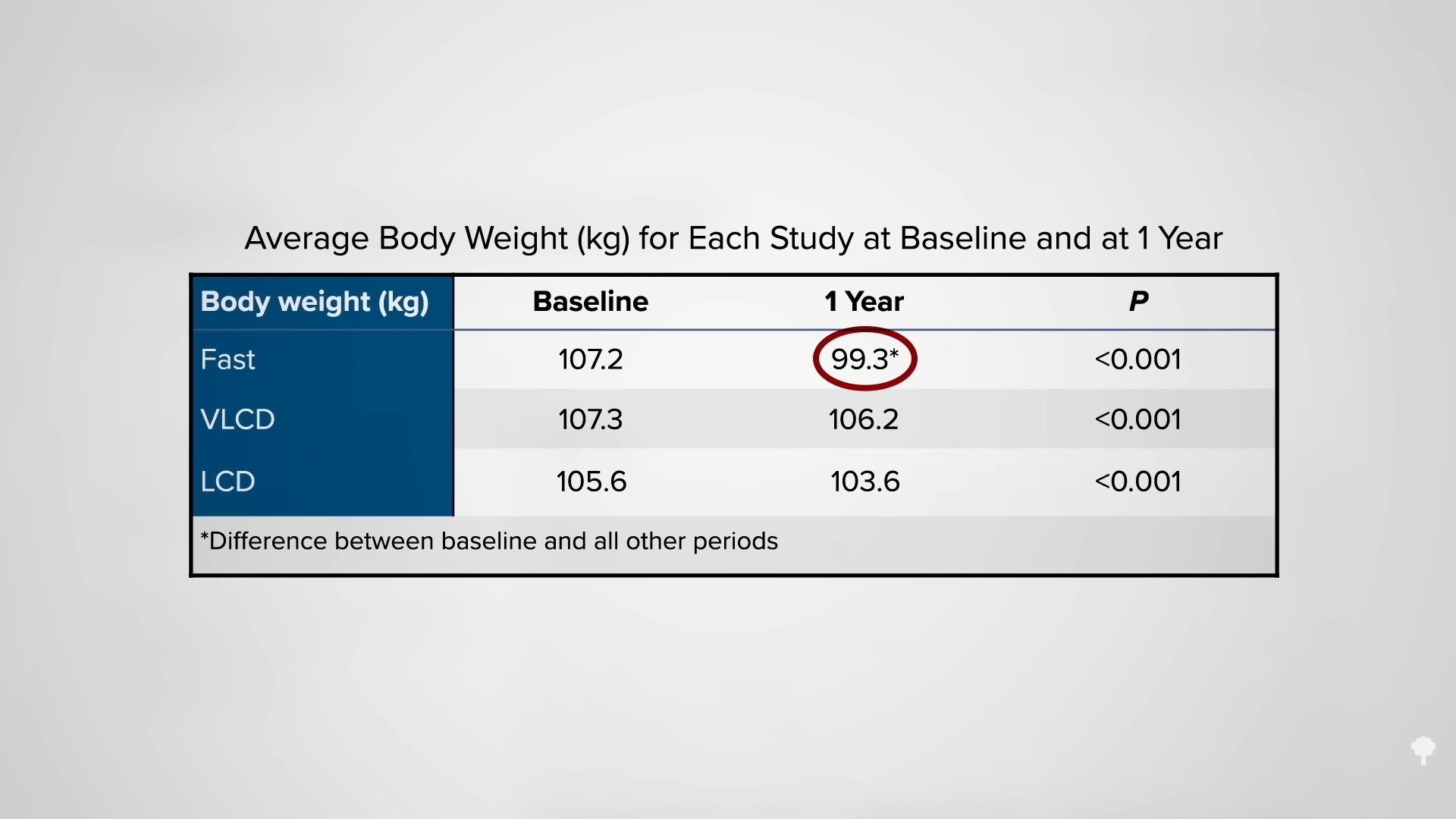

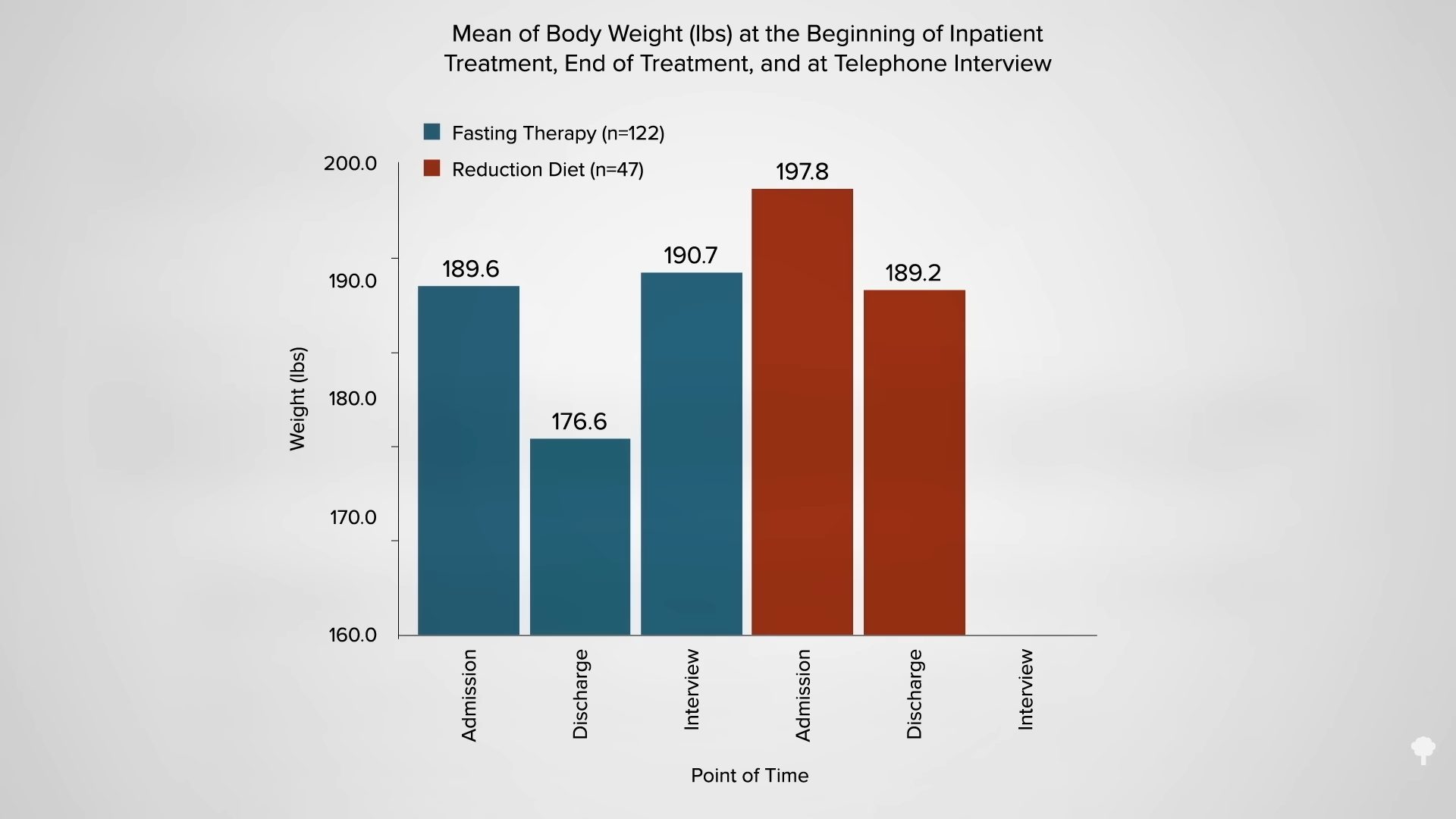

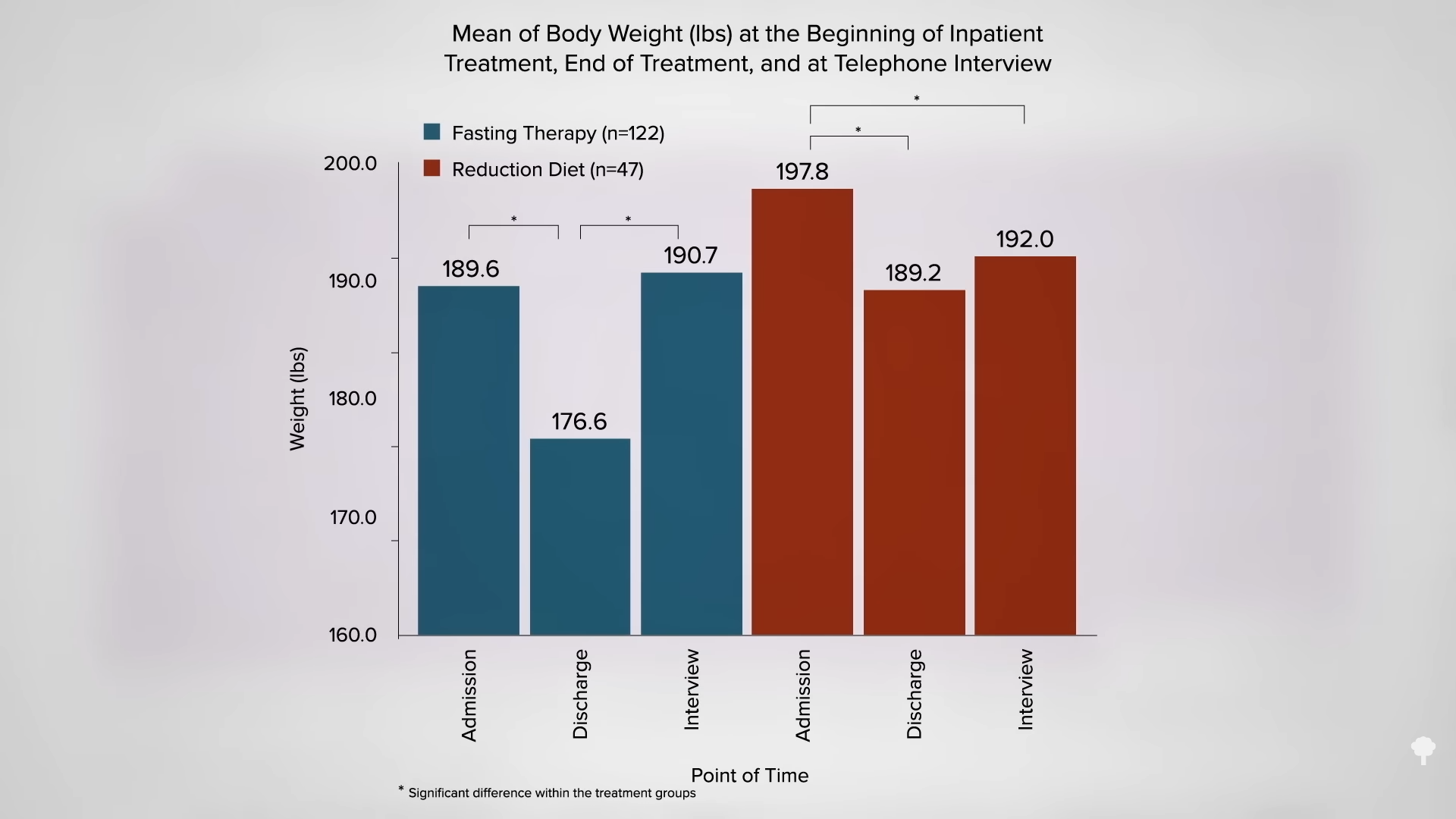

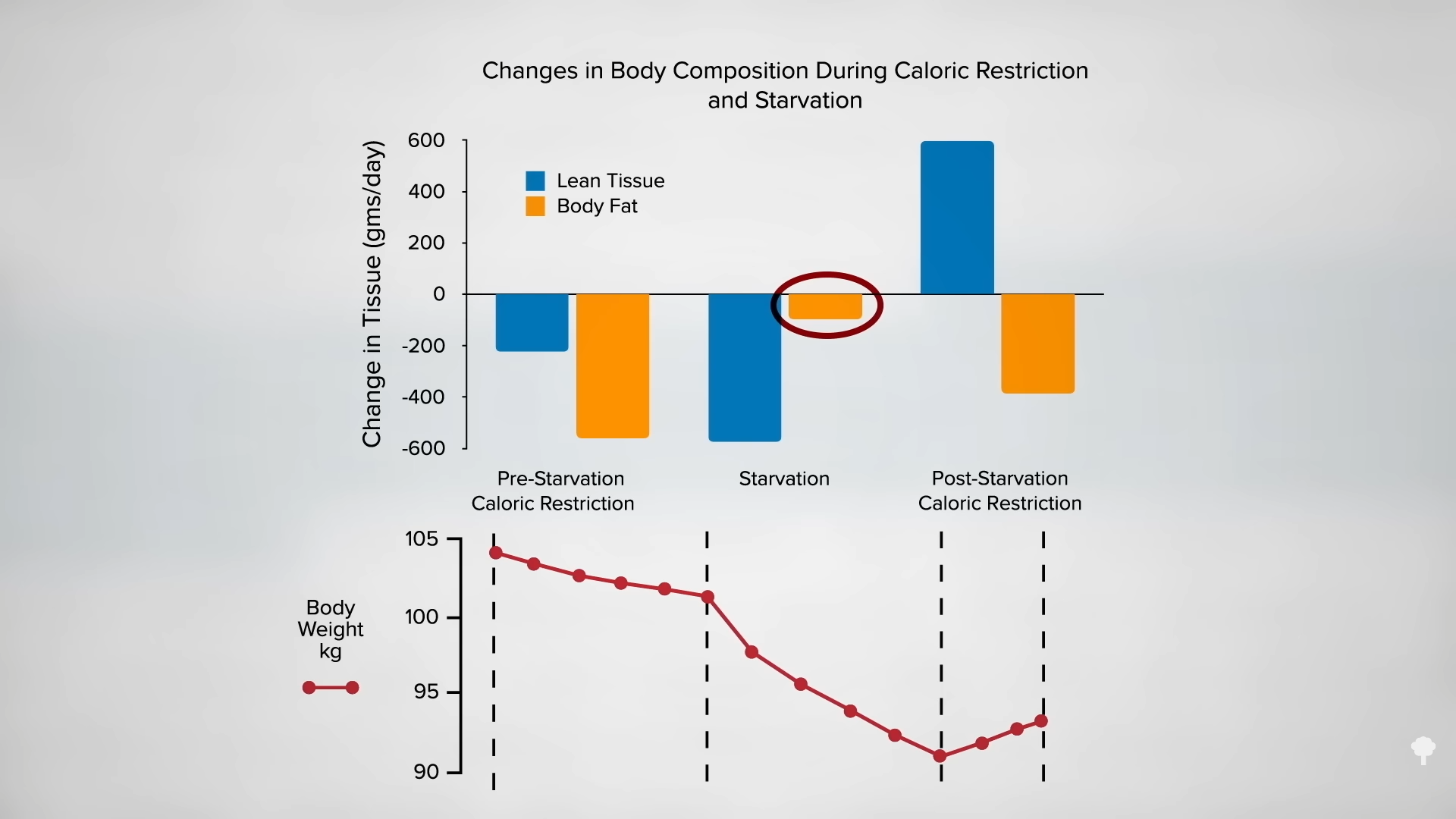

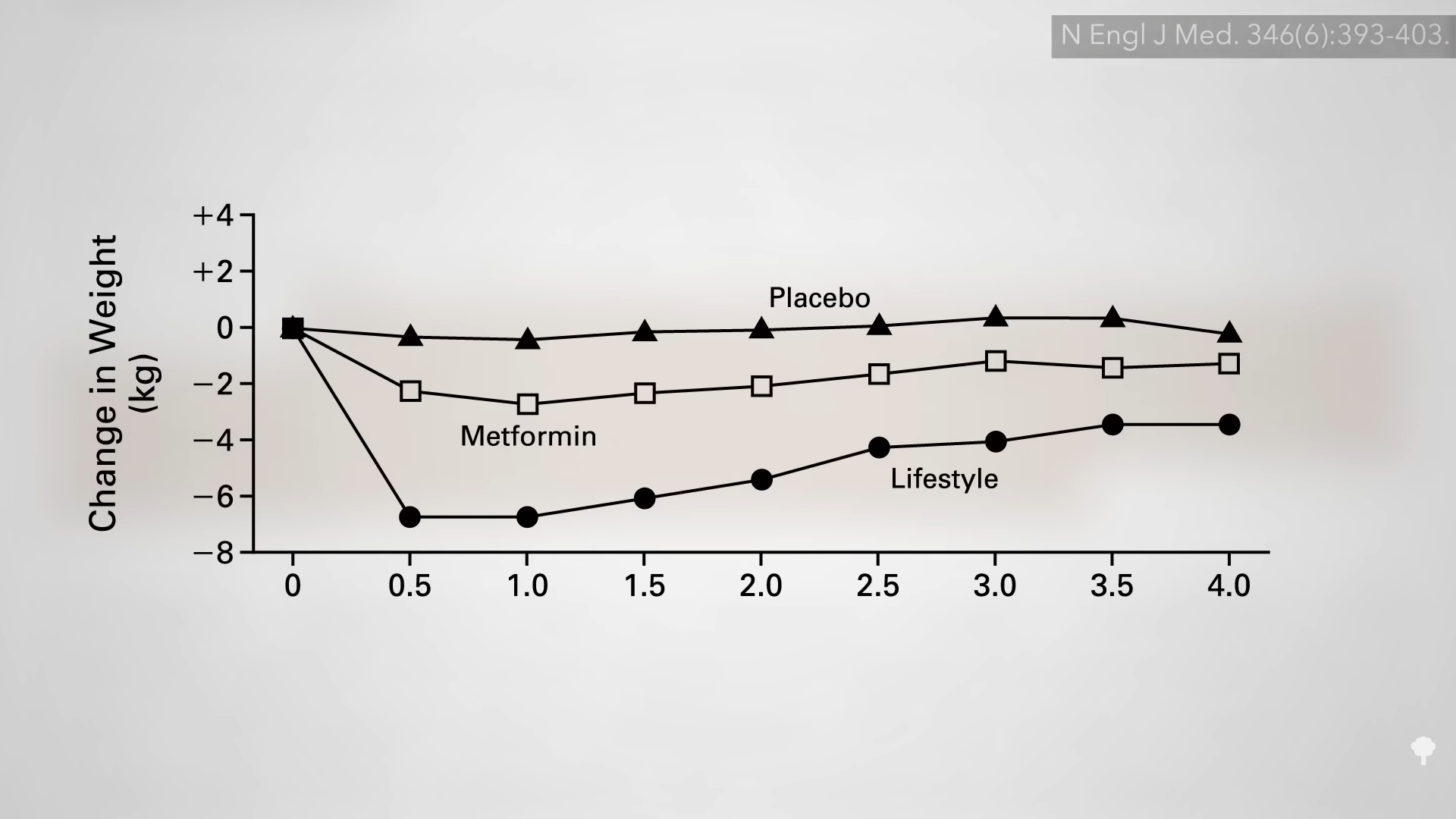

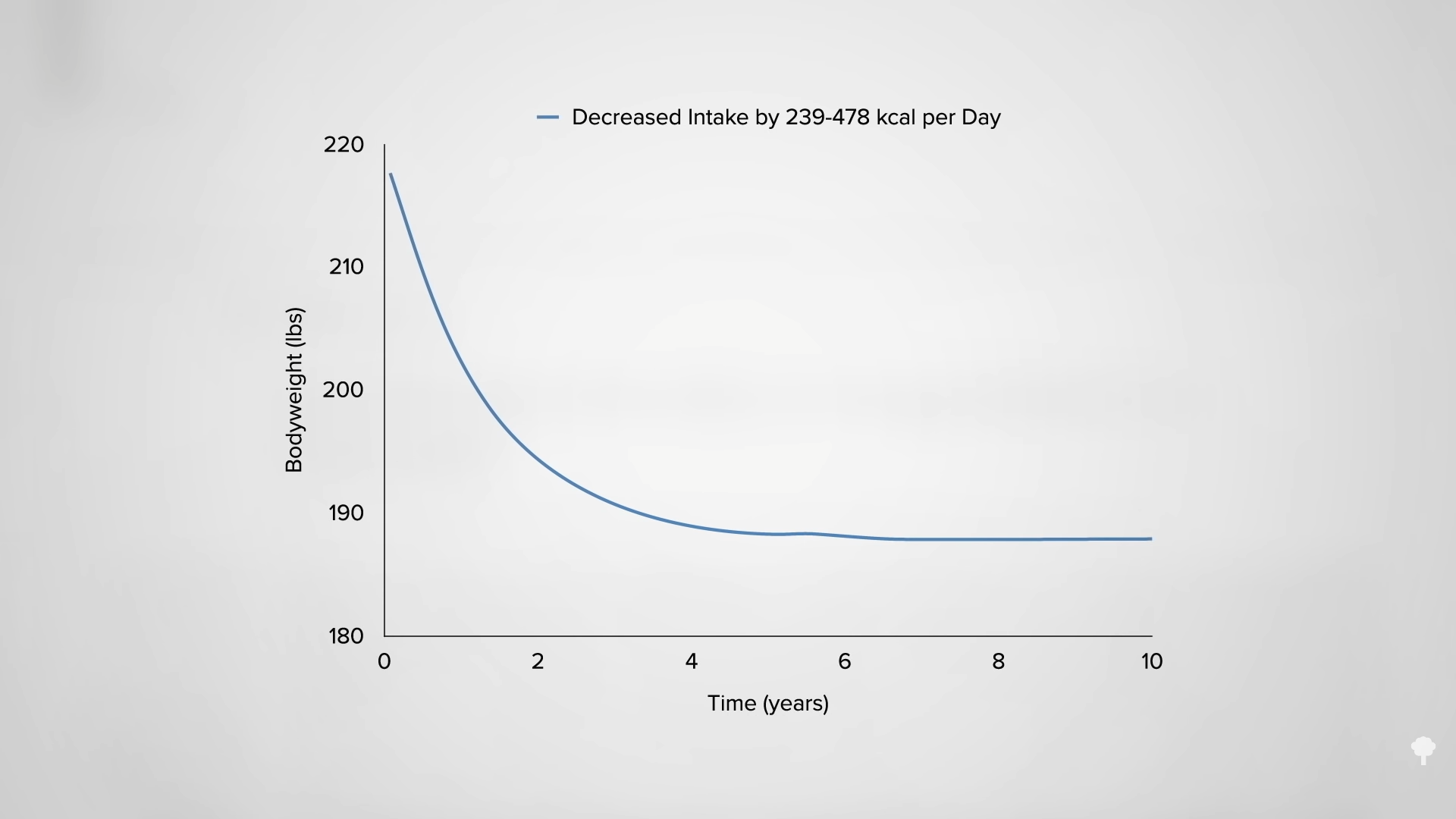

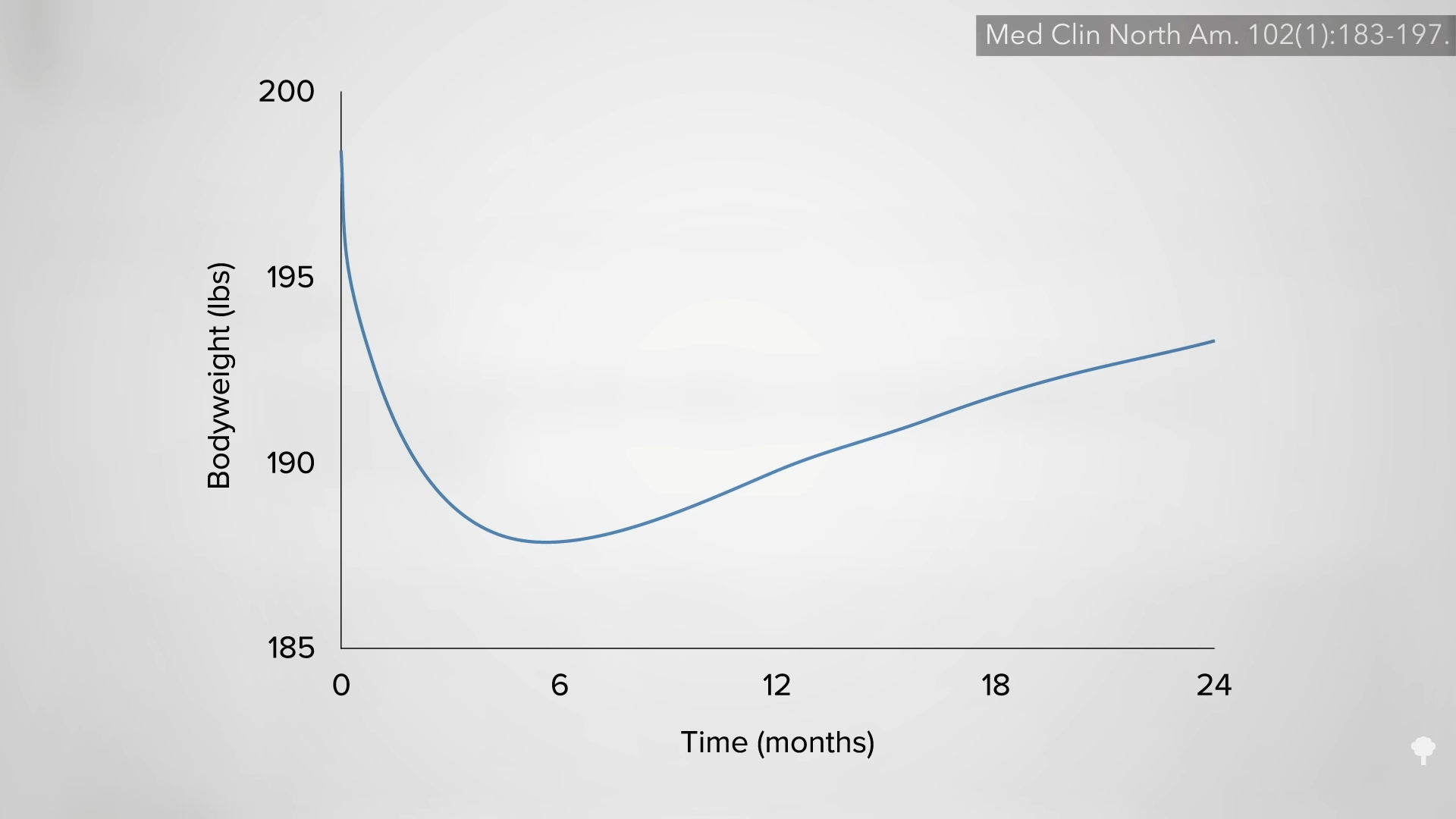

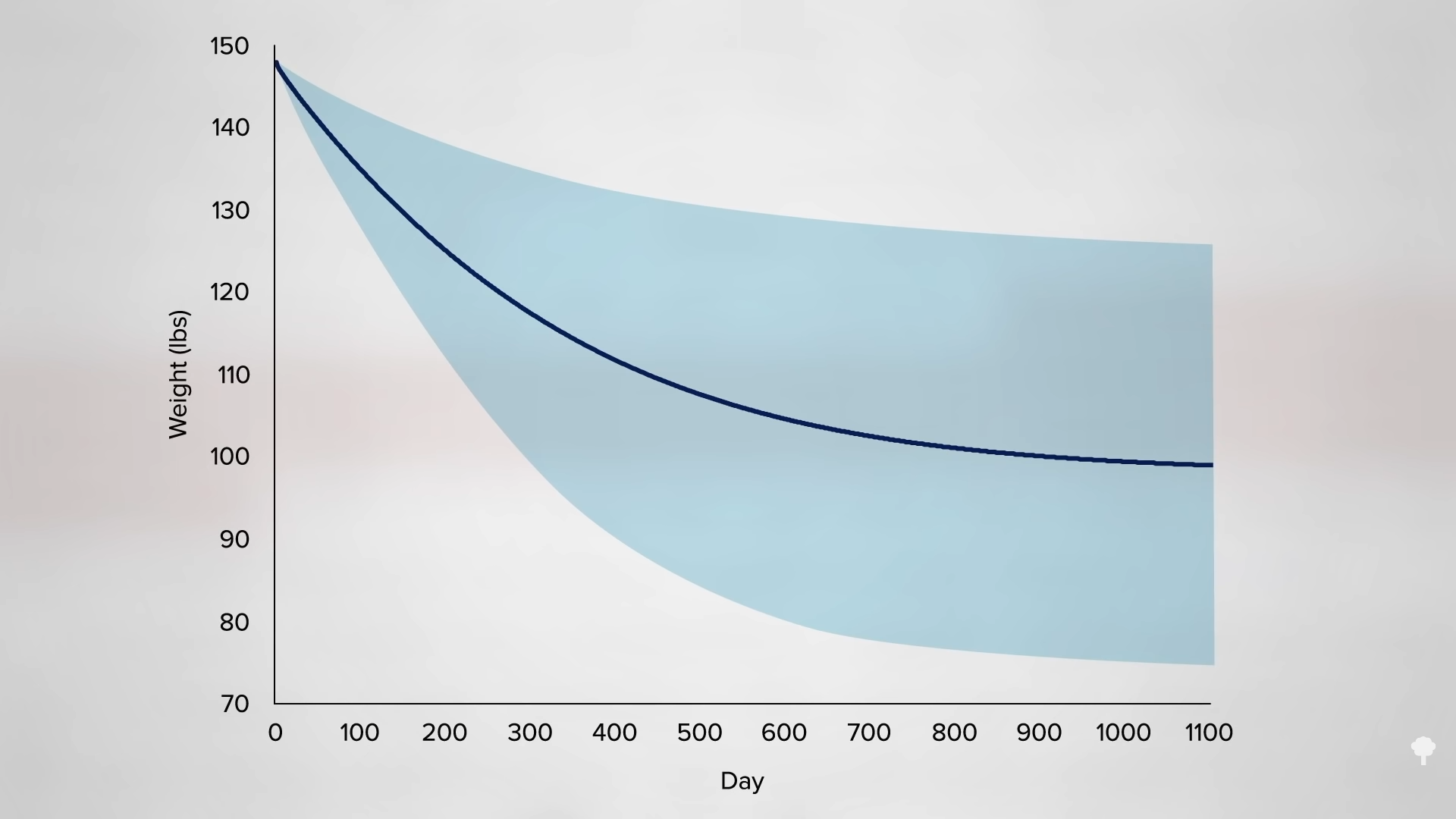

Therapeutic fasting for obesity has largely been abandoned by the medical community not only because of its uncertain safety profile but its questionable short- and long-term efficacy. Remember, for a fast that only lasts a week or two, you might be able to lose as much body fat or even more on a low-calorie diet than a no-calorie diet.

Fasting for a week or two can actually interfere with the loss of body fat. For more background on this, see Is Fasting Beneficial for Weight Loss? and Benefits of Fasting for Weight Loss Put to the Test.

If you’re wondering what the best way to lose weight is, I wrote a whole book about it! Check out How Not to Diet.

Interested in learning more about fasting? See related videos below.

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

Source link

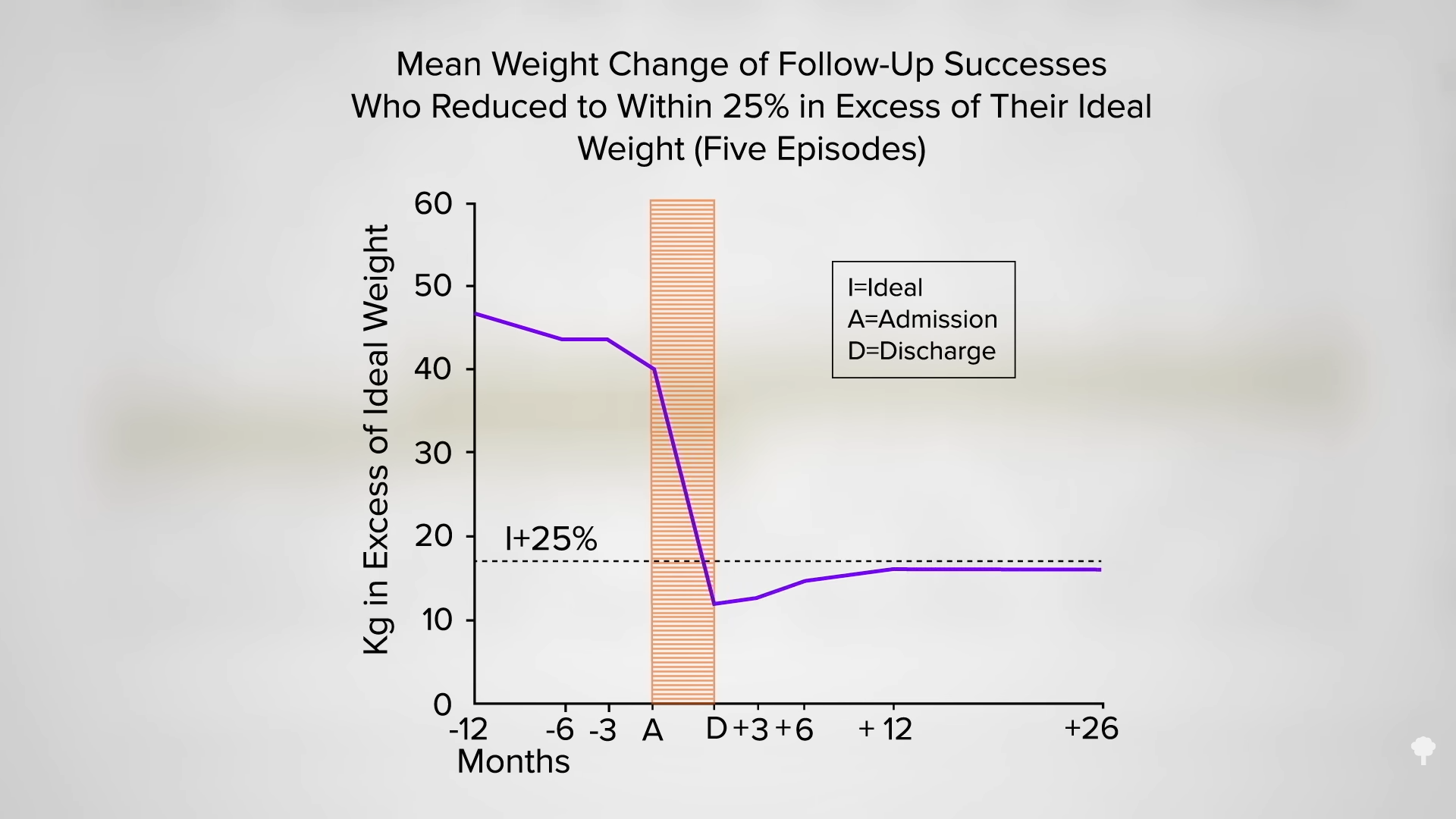

What happened nine years later? “Therapeutic Fasting in Morbid Obesity”

What happened nine years later? “Therapeutic Fasting in Morbid Obesity”  The small minority for whom fasting

The small minority for whom fasting

This is the follow-up to

This is the follow-up to

In my previous video, I dive into how

In my previous video, I dive into how

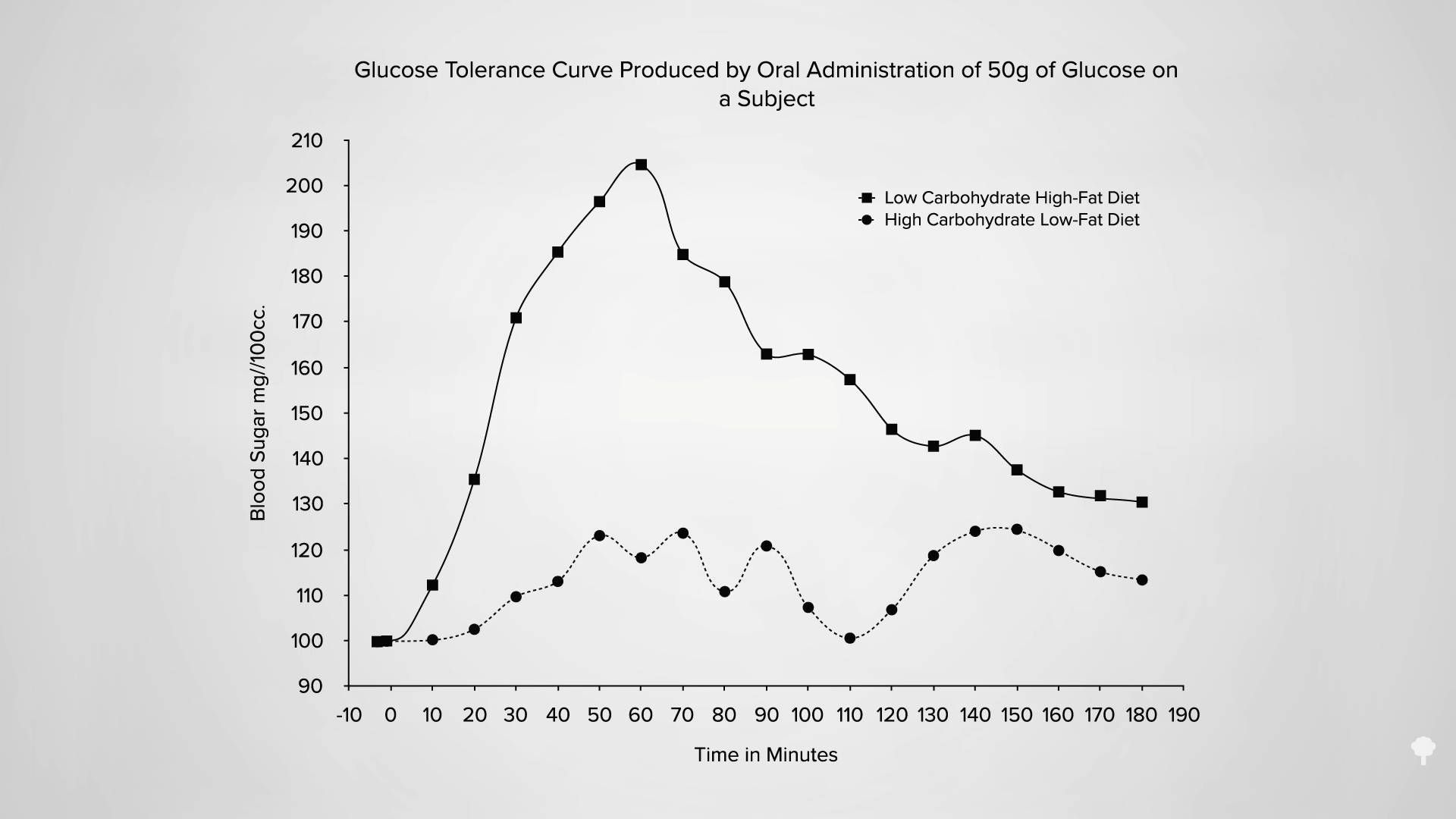

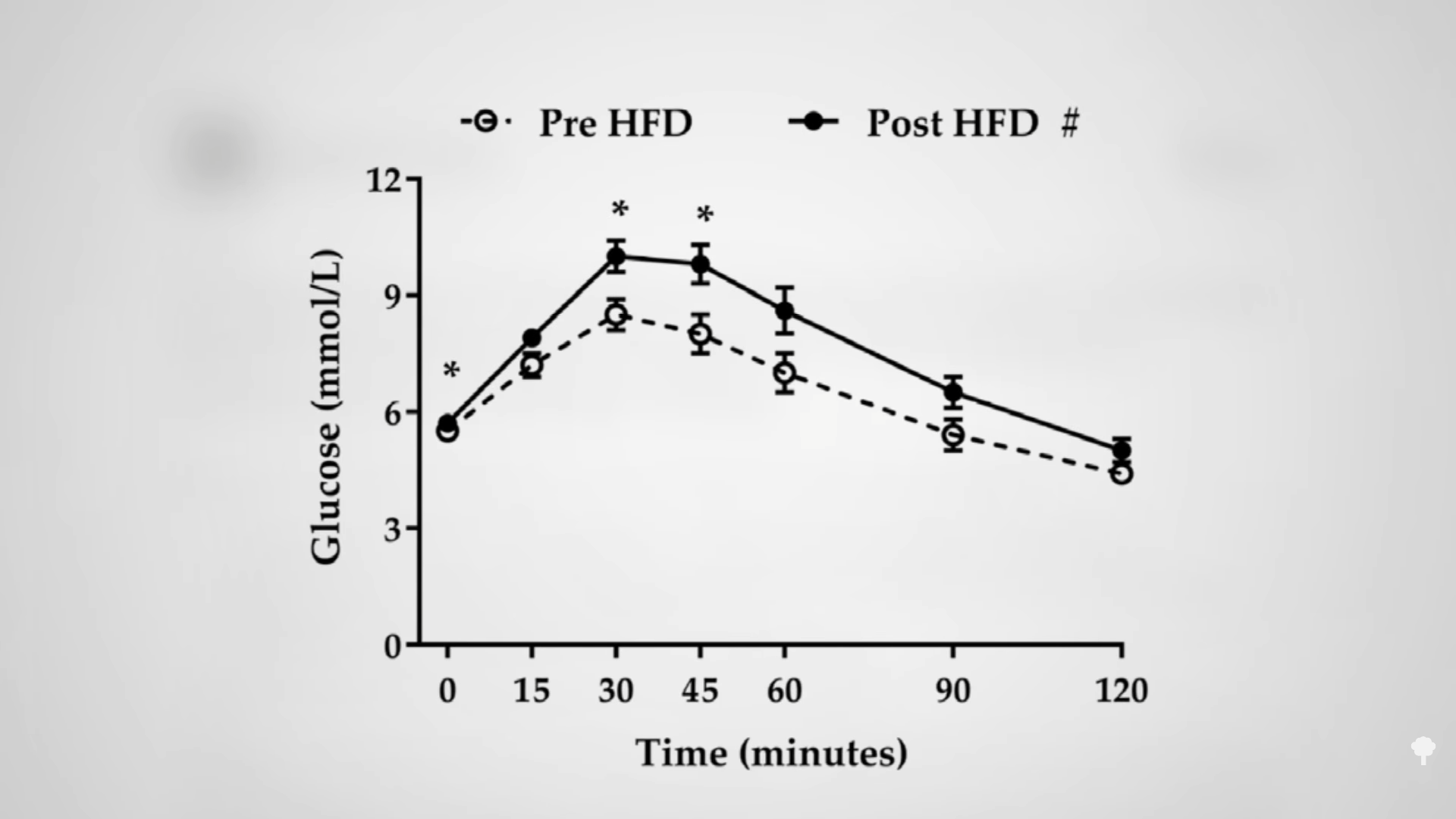

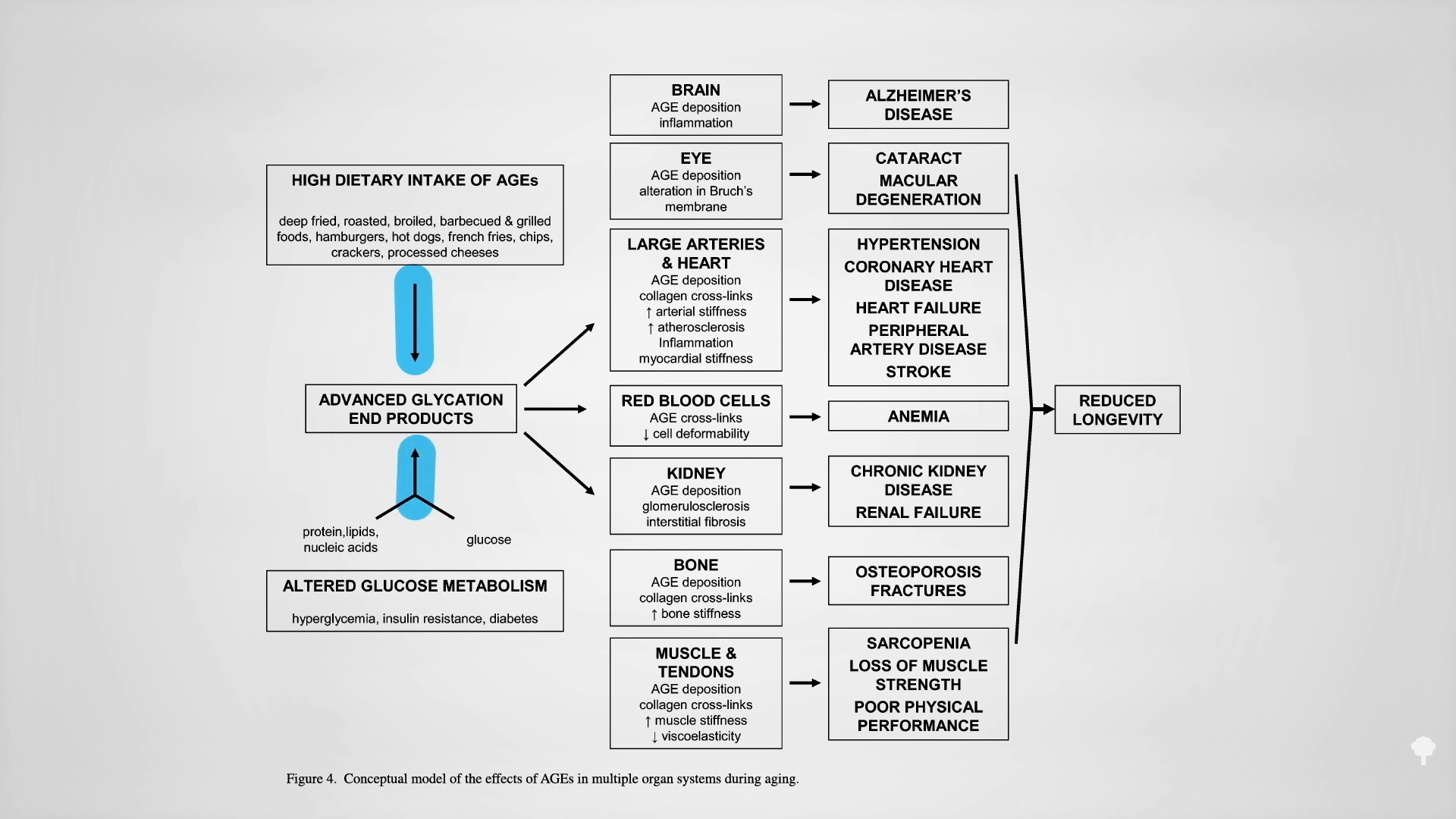

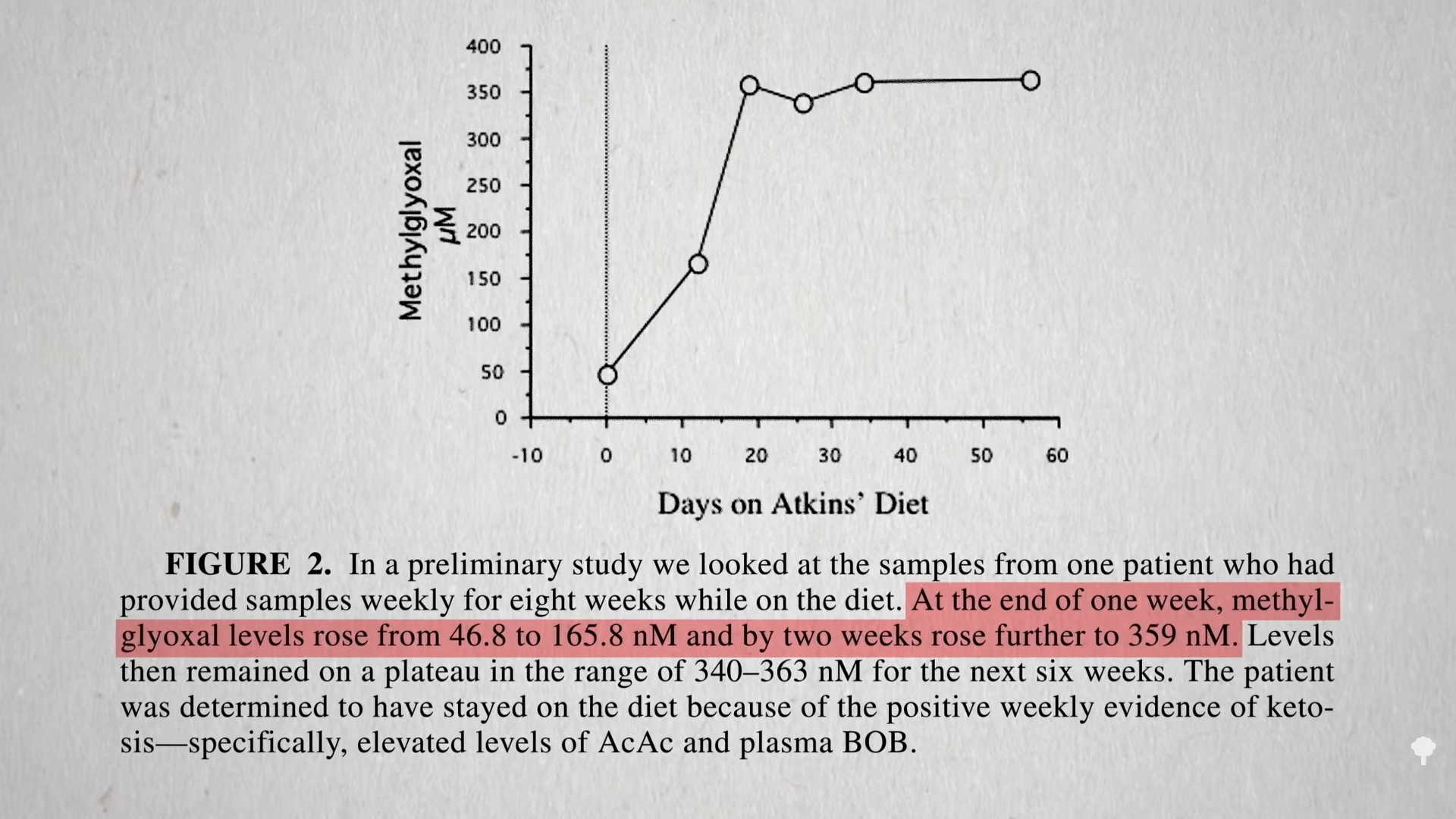

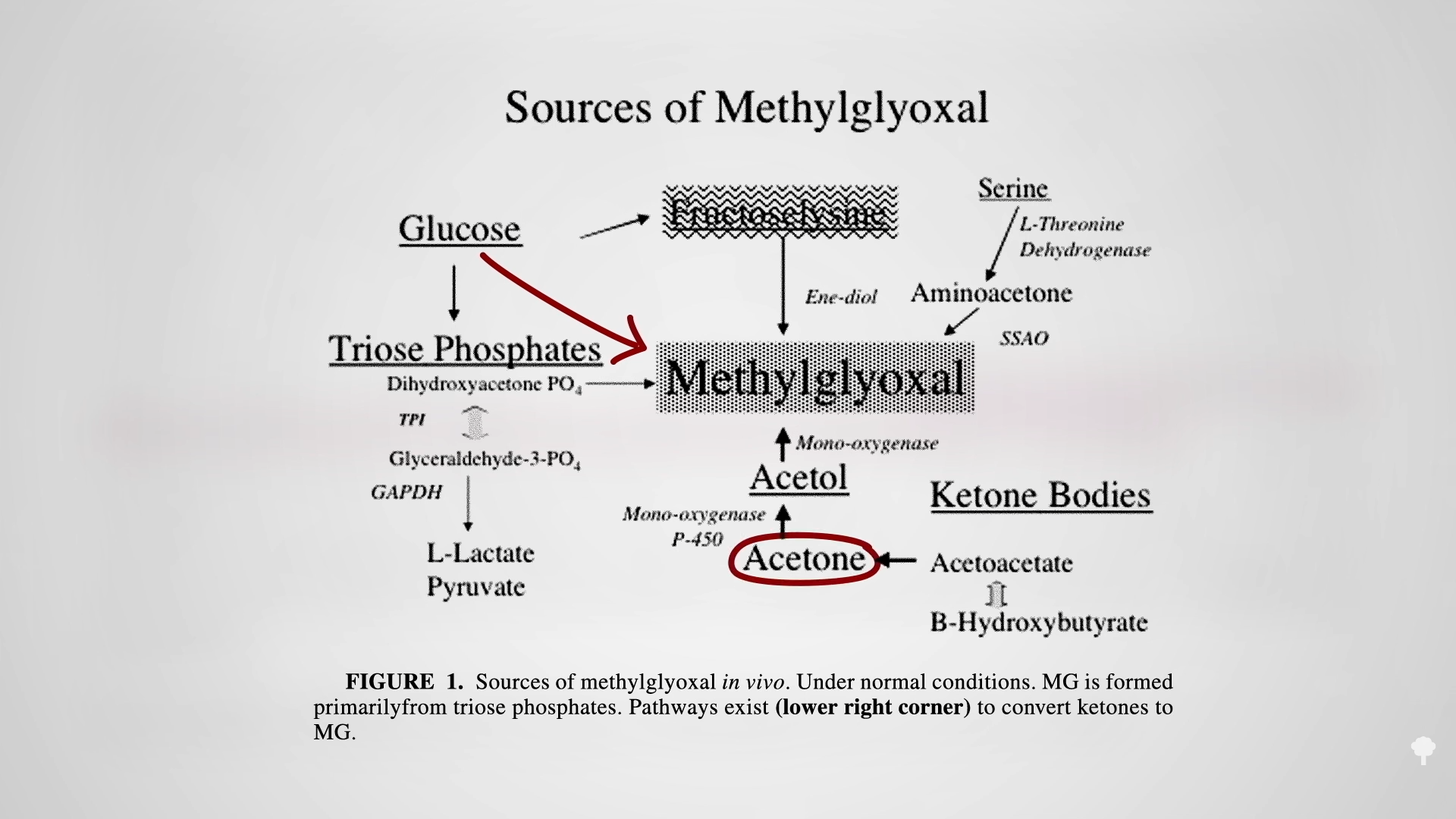

The irony doesn’t stop there. One of the reasons people with diabetes suffer such nerve and artery damage is due to an inflammatory metabolic toxin known as methylglyoxal, which forms at high blood sugar levels. Methylglyoxal

The irony doesn’t stop there. One of the reasons people with diabetes suffer such nerve and artery damage is due to an inflammatory metabolic toxin known as methylglyoxal, which forms at high blood sugar levels. Methylglyoxal

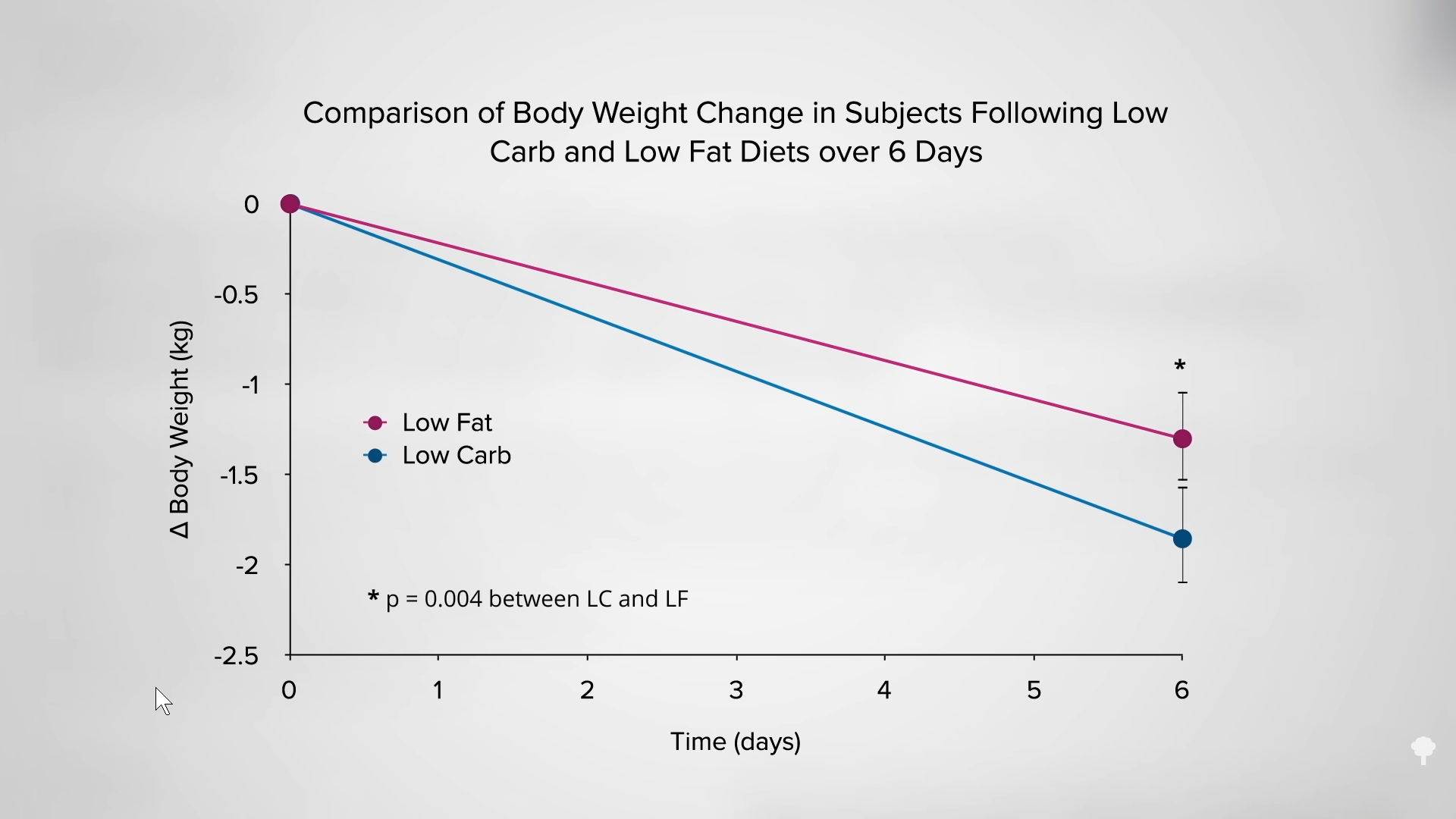

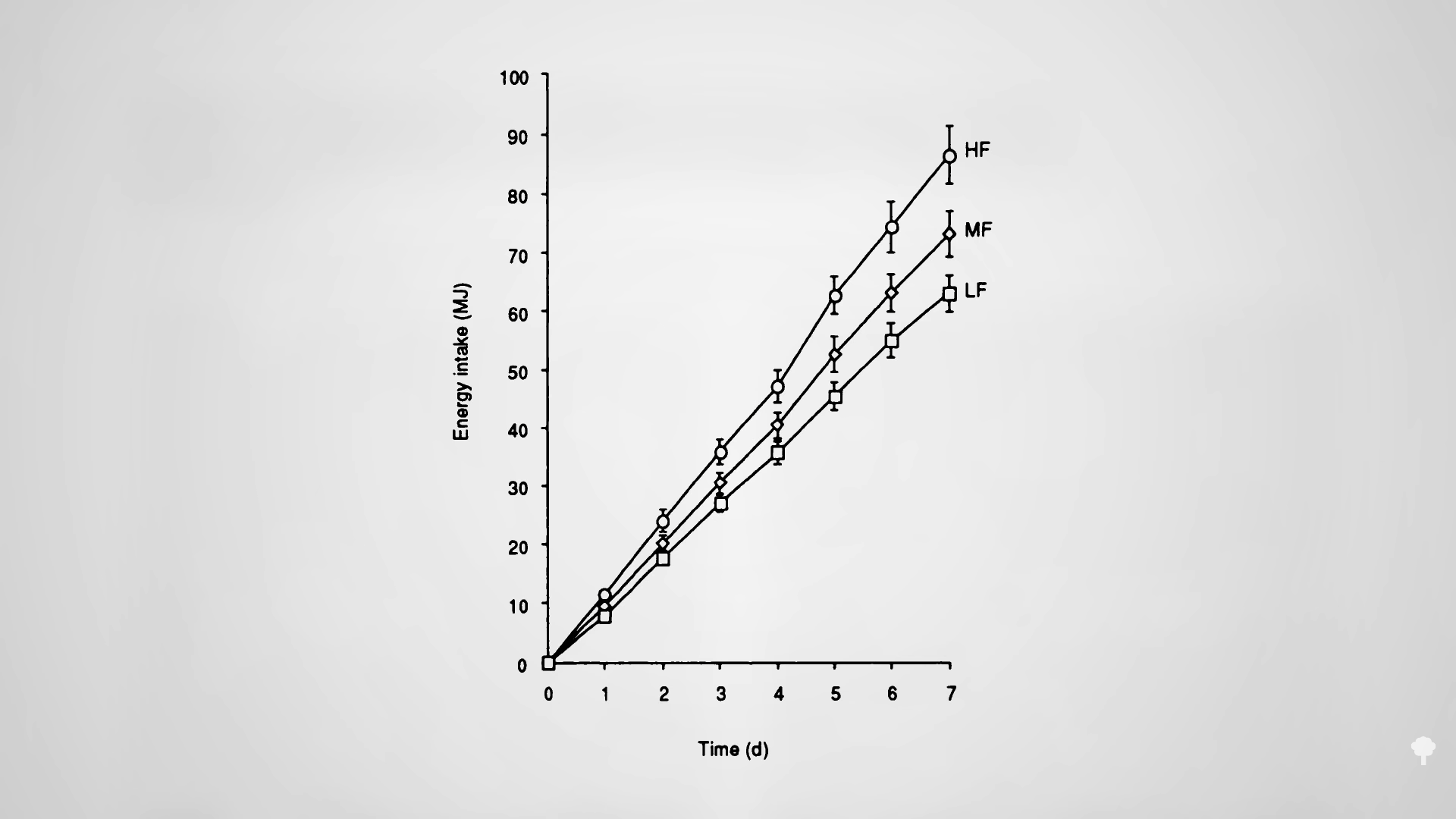

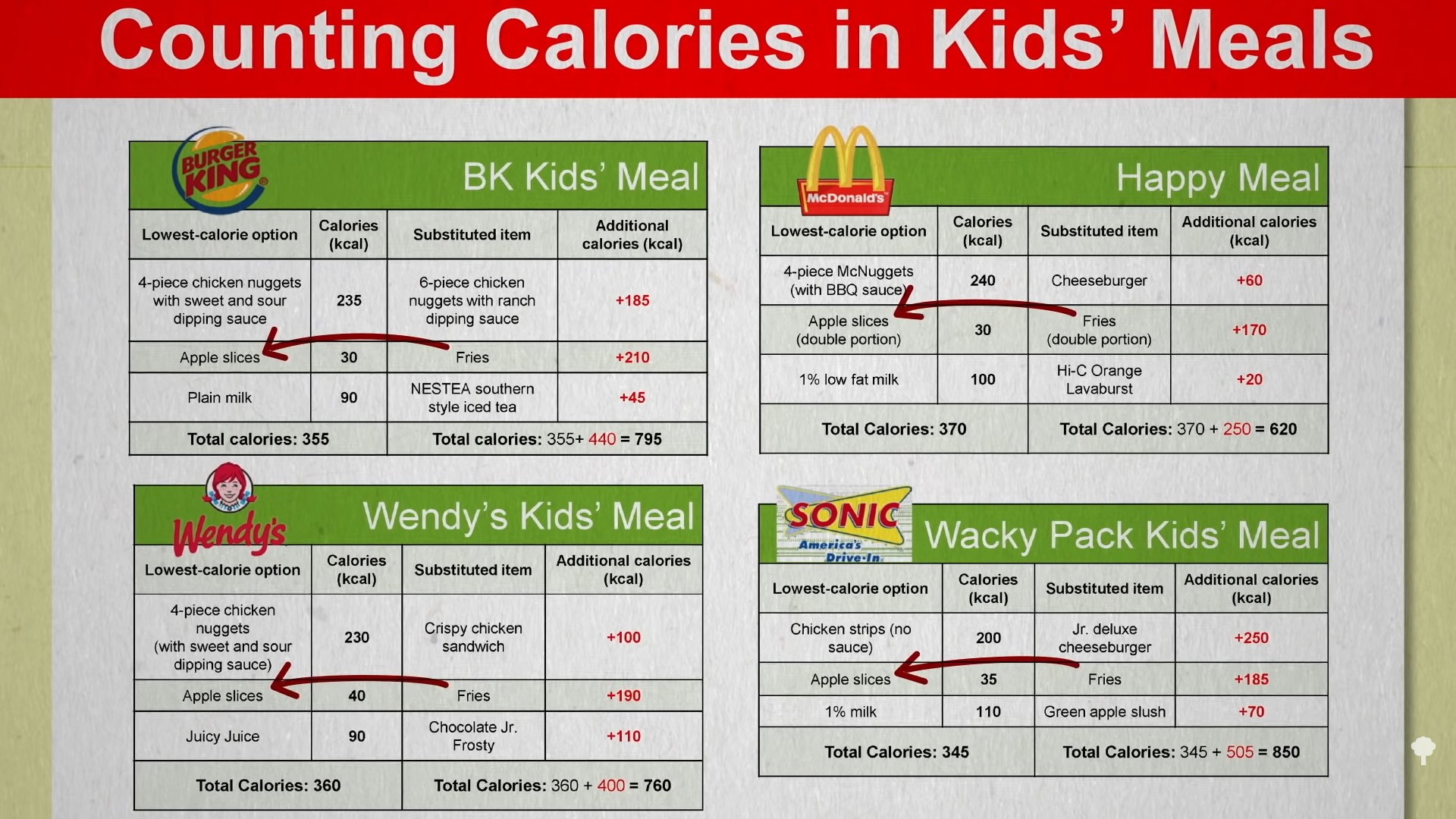

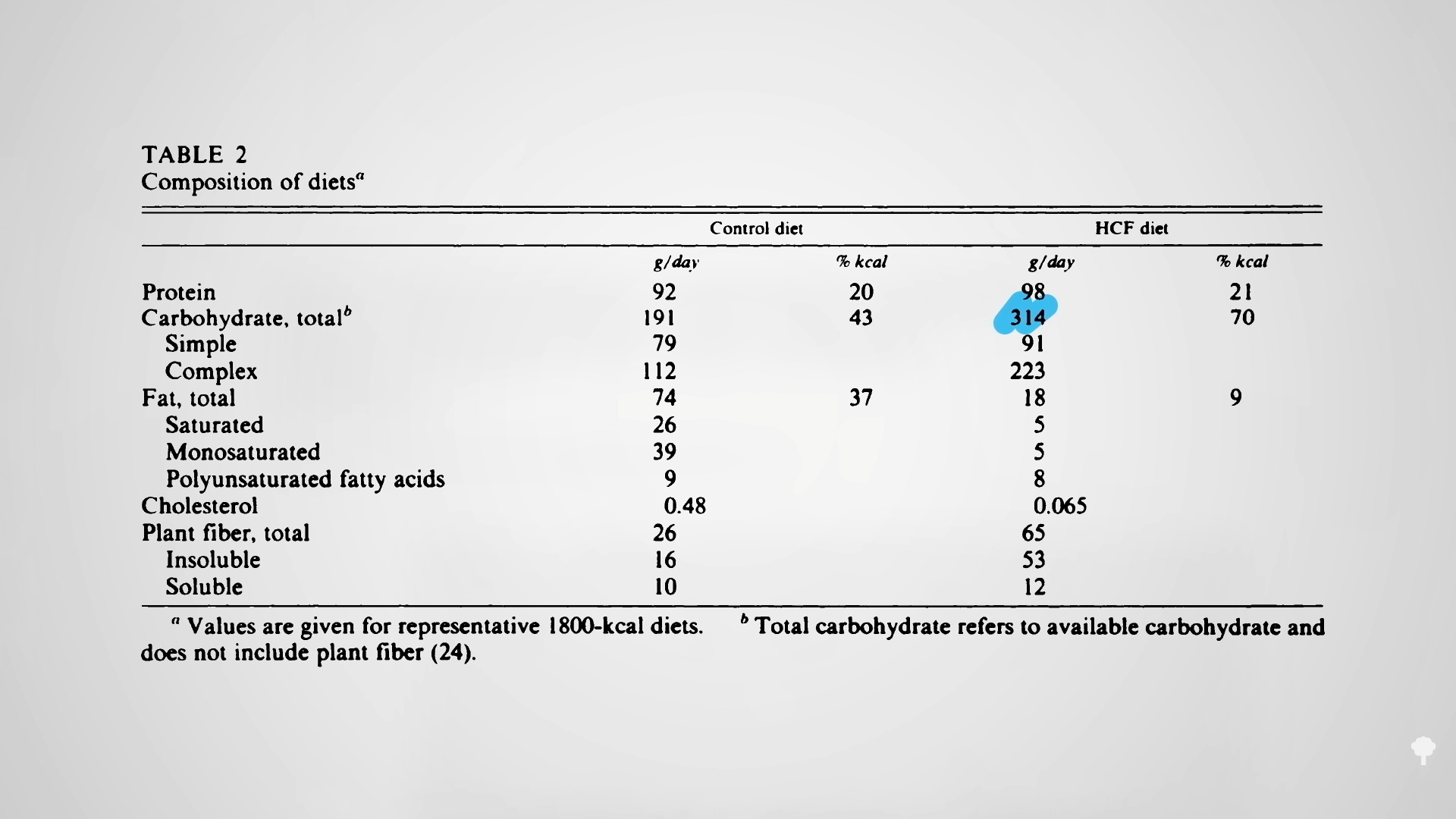

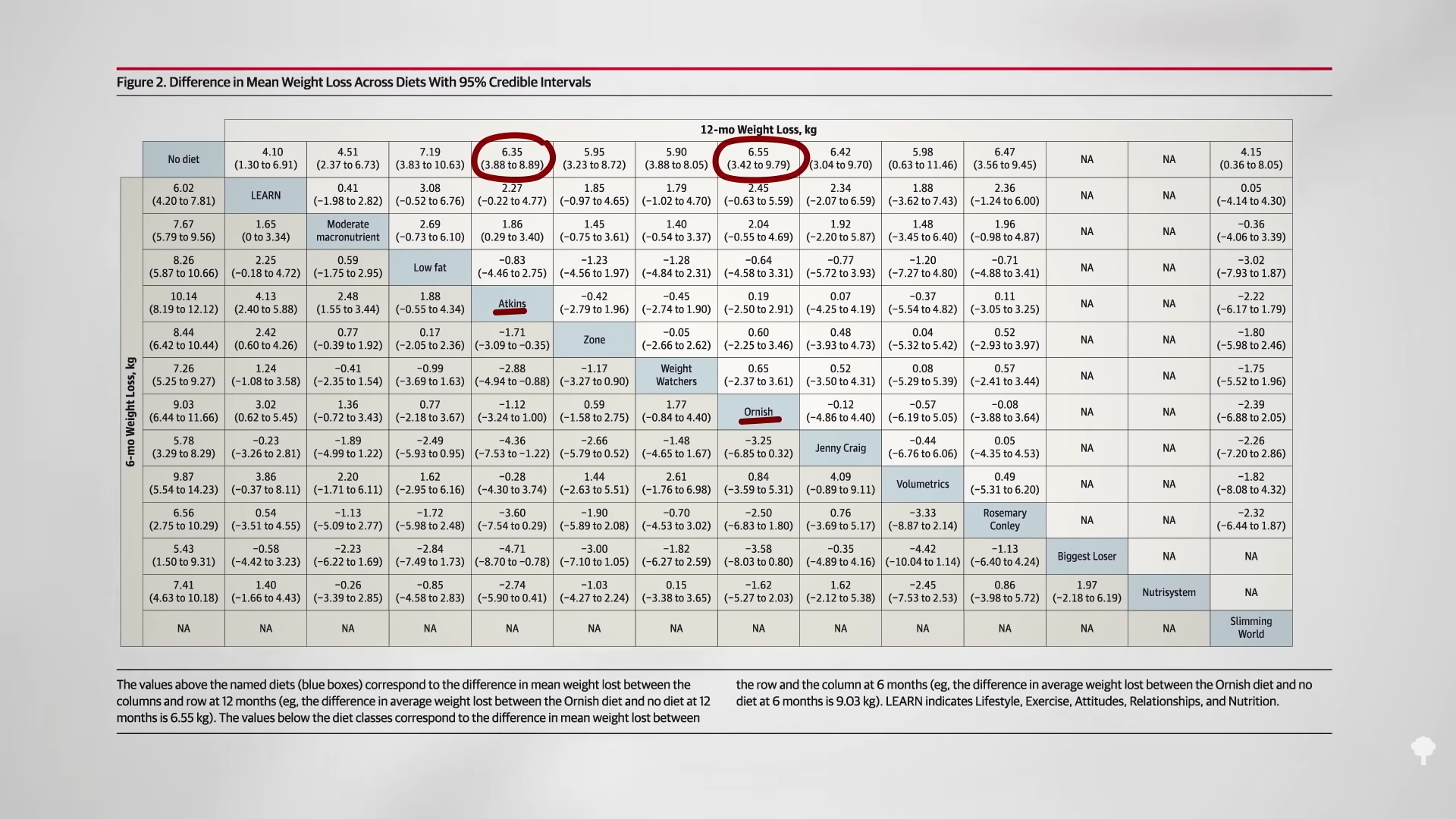

Low-carb diets cut down on refined grains and added sugars, and low-fat diets tend to cut down on added fats and meat, so they both tell people to cut down on donuts. Any diet that does that already has a leg up. I figure a don’t-eat-anything-that-starts-with-the-letter-D diet could also successfully cause weight loss if it caused people to cut down on donuts, danishes, and Doritos, even if it makes no nutritional sense to exclude something like dill.

Low-carb diets cut down on refined grains and added sugars, and low-fat diets tend to cut down on added fats and meat, so they both tell people to cut down on donuts. Any diet that does that already has a leg up. I figure a don’t-eat-anything-that-starts-with-the-letter-D diet could also successfully cause weight loss if it caused people to cut down on donuts, danishes, and Doritos, even if it makes no nutritional sense to exclude something like dill.