“’Museums Without Men’… ‘The Story of Art Without Men’… these are tongue-in-cheek attention-grabbing titles. Because it raises awareness: why museums without men?” Katy Hessel tells Observer. Championing a fiercely feminist re-reading of art, past and present, is Hessel’s signature. If you’re not familiar with her name, you’re likely familiar with her work. She is behind the Great Women Artists podcast and a runaway-hit Instagram account (@thegreatwomenartists), in addition to having published the best-selling The Story of Art Without Men. Said book—a compendium of women artists from the Renaissance to today in direct response to E.H. Gombrich’s women-absentee The Story of Art—was mostly championed for its corrective historical narrative, shrugging off the occasional dismissive accusations of being “tinged with the boosterism of girlboss feminism.”

To celebrate Women’s History Month, Katy Hessel launched Museums Without Men, a new but ongoing series of audio guides highlighting women and gender non-conforming artists in the public collections of international museums. The series launched with five participating institutions. The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art were first, and the Hepworth Wakefield in England, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. and Tate Britain soon followed.

Observer recently spoke with Hessel—who was included in our 2023 list of The Most Influential People in the Art World—about making museums accessible, non-binary artists to know, and thinking more carefully about museum captions.

To start, how did these guides come to be?

The Met was first—it was only sort of meant to be a one-off thing that I was doing with them. The guides are created for lots of different reasons. One was the fact that when you go into museums, oftentimes you’re overwhelmed by the number of works on display, and what you really want to do is spend time with seven or eight works—as much as it kills you—but really sort of get into it and leave the museum being like I really looked at something properly today. The whole point of my work is to get as many people into the museum as possible.

Whenever I go to museums, obviously I always look at the label and see if it’s a woman, because that’s how I’ve discovered and learned about so many artists. Not only does that bring me into these artists’ lives and work but it also makes me realize how many women artists are being collected by these institutions—and reveals the shocking gender imbalance.

You communicate through many media: an engaged Instagram, a book, a column in The Guardian, a podcast. Are these guides a complement to what you’re already doing? Or do you see this as something separate?

I always think: what can I give people that will help them? Instagram serves a purpose, which is a daily dose of artists or artworks; it’s very condensed, it’s surface level. The book is a compilation of everything. It breaks my heart to have written just 400 words on Cindy Sherman—it shouldn’t be allowed—but you could also go to my podcast and listen to an episode with William J. Simmons, who’s one of the leading scholars on Sherman. The podcast is a whole hour to learn about an artist: it’s with a world expert, or it’s with the artist, and it’s hopefully this fantastic insight. It’s about saying to people, no matter where you enter from: welcome. You can go as deep—or not—as you like.

Do you think men will pick up the guides too?

I think it’s for everyone. There’s nothing inherently different about art created by a different gender; it’s more that society and gatekeepers have prioritized one group in history.

The National Gallery—not that I work with the National Gallery yet—has 1 percent women artists. However much I wish I could take out all the works and replace them with women artists, or make it equal, I can’t do that. What we can do is draw attention to these different artists in the museum and hopefully that will help. It’s a tiny way to raise awareness for the visitor, to realize that there’s more work to do, to introduce new names—and also for the museums to be like actually, we really need to focus on our representation here. They’re just missing out on great works.

But how do we get men to feel implicated? Men may acknowledge it’s unfair that parity is far from being reached in a museum setting, as elsewhere, but that may not necessarily galvanize them to listen. I imagine with other media you’re involved in, it’s primarily women who are engaging?

It’s definitely majority women—but I engaged with so many male curators for this, and museum directors who were men and who were supportive of it. I hope that it’s for everyone. Curator Furio Rinaldi at the Legion of Honor, with whom I worked closely on the Mary Cassatt and the Leonor Fini work is curating the first-ever North American solo exhibition of Tamara de Lempicka, who was one of the most incredible artists of the 20th century yet has never had a major solo show in the U.S.

“Museums Without Men,” “The Story of Art Without Men”—these are tongue-in-cheek attention-grabbing titles. Because it raises awareness: why museums without men? Well, because historically most of these museums were Museums Without Women. And so, we need to talk about that. I want to invite everyone in because it’s about introducing people to artists they might not know. I hope that men enjoy it—it’s for them too, completely. And from a position of privilege that anyone stands in, there should always be interest in a different perspective. I don’t only want to learn about people who look like me. I want to learn about all sorts of people.

The press release mentioned that the artists featured are women and non-binary. Could you give an example or two of some of the non-binary artists?

Absolutely. We’ve got people like Gluck [Hannah Gluckstein], who was a fantastic artist working at the start of the 20th Century. They were based in London, where they did portraits of the queer community in the 1920s and 1930s. Virginia Woolf was writing Orlando.

There’s a fantastic artist called Rene Matić, a photographer whose work is at the Hepworth Wakefield. It’s this really beautiful series where they follow their friend Travis Alabanza, who’s a performance artist. There are gorgeous pictures of dressing rooms and quiet moments and the trust that people have to let each other into their very personal lives.

There’s a forthcoming expansion of the guides to Vienna, Austria—do you have other target venues that you can speak about? What is the scope that you have in mind for the guides?

I would love to take it global: the dream would be to work with museums and have translations. I only speak English, sadly, so I’ve done lots of projects and speaking engagements in America. That’s why we started with English-speaking places. There has been interest from other institutions since we launched. But yes, I hope it’s just the beginning of something—we’ll see.

Has there been more interest in contemporary versus historical women artists? Obviously, there’s a smaller pool historically, but have you noticed people gravitating toward anywhere in particular in the timeline of women artists?

I have never noticed that. My pool spans a whole millennium… I think it’s a mix. It’s always exciting talking about someone historic because you can talk about that from a very contemporary point of view. The work has outlived this person maybe for 500 years, but that doesn’t make it any less contemporary than works we’re looking at. And thinking about where the work is in the space, as well, and how it feeds the other works around it and how maybe we can look differently at them… When I was in San Francisco in November, I did the Louise Nevelson tour, and I looked at Robert Motherwell next to her and I saw him in a completely different light because of that.

In terms of the way museums have been pledging to aim for parity—however far away that may be—you used the word “accelerate” relative to the guides changing the pace at which people are focusing on women artists. How much have you seen that acceleration at play? As you’re speaking with curators and directors in institutions, what is your sense of the future?

I think it’s about having certain people who have the power at the moment. They’re conscious of what is in museums and what work needs to be done. I remember speaking with Emily Beeny, a curator at the Legion of Honor, about Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Cupid and Psyche. It’s a really interesting painting of this well-known Greek myth, but Cupid is not even present. Benoist was really telling this work from Psyche’s point of view. I find it fascinating that certain curators, and those who have power in museums, are saying: We need to be collecting this kind of work because we need a balanced perspective of what history is. Otherwise we’re getting a skewed idea of what happened before us. I wouldn’t say it was by chance that there’s a plethora of female directors, which ties in with the correlation of more representation.

Not to say that the men in charge aren’t conscientious—of course they are. Let’s just say the people who are in charge of a lot of museums are now very conscientious about representation. We can all do things that are in our own remit to help accelerate equality for anything, whether it’s supporting a business or buying a book. My thing is: I can make audio guides and I have a platform to do that, so why not use that in a positive way?

Do you get pushback from people who feel that using a gendered lens to go through a museum is flattening in some way? What is your response to that criticism?

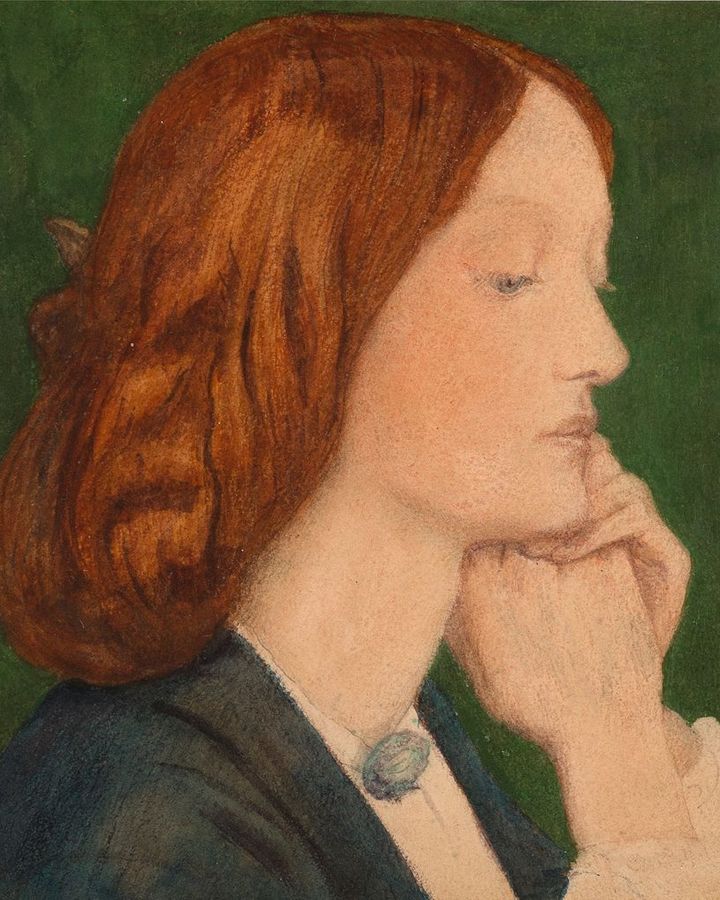

I haven’t personally received any feedback like that. This is totally not prescribing that this has to be the way that people enter museums. I think it’s nice that it’s an option. People are excited about it because perhaps they won’t realize that a work is by a woman. In the Met audio guide, we were in this room in the European galleries—a sea of Courbet nudes! The female nude in her glory. Then there is this huge painting by Rosa Bonheur of the horse fair, and it just towers over every other work. To know that that’s by a woman, in this room, is extraordinary—the lengths she had to go to, to paint that.

Similarly, in the de Young Museum, there’s a fantastic moment of American realism in the 1930s with these images of farms and quite mundane family dinner settings in a working environment. And in the middle is this amazing sculpture from 2020 by Elizabeth Catlett. It’s the center of all these works that are by men, and the story is very much dominated by the male narrative—but then you have Stepping Out, which puts her in a very important place.

People don’t need to abide by my guides; they’re just to help them through. I often take friends to museums and pick out five to seven works I want to show them. What I do for my friends, I made into a guide.

There was a Rosa Bonheur exhibition in France last year at the Musée d’Orsay, and I was appalled by the text in the museum, which was very elliptical about her queer identity, saying instead that she ‘lived with a friend for a long time.’ The text refused to engage overtly with her queer identity. Some museums remain very conservative.

It’s ridiculous. How we contextualize artists is so important. I was at the National Gallery the other day, and I went to look at works by women artists—and every single gallery label for women artists, all about fifty words, included a male artist’s name. For Artemisia Gentileschi, it said she was the daughter of Orazio Gentileschi, who was the contemporary of Caravaggio. Or for Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who—it said in the first line—this work is a response to a Rubens self-portrait. No one is writing of Orazio Gentileschi that Artemisia Gentileschi is his daughter—which is really what they should be saying.

It’s about making sure you contextualize them in a respectful way. Personally, to say someone has a queer identity, it’s just a normal thing, and it’s about normalizing the way that people live. Because there is no shame in that. And I hope I can be respectful to all different people with these guides.

I don’t assume that people know who Artemisia Gentileschi is. It’s not a definitive thing for the artists. It’s a nice resource. I hope it encourages people to take something from it and have their own interpretations. Creating these was even great for me to get to know new work—it led me down rabbit holes for artists I thought I knew so well!

Sarah Moroz

Source link