(Image credit: Museum of Fine Arts Boston)

A new exhibition at Tate Britain celebrates the ‘strange and extreme’ world of the Rossetti family, who challenged conventions in art and life, writes Matthew Wilson.

M

Meet the Rossettis: Christina, her brother Dante Gabriel, and his wife Elizabeth. Their art and poetry stunned Victorian Britain, but is their greatest legacy to be found mostly in their output, or their spirit of bohemianism? The Rossettis, a new exhibition at Tate Britain, invites us into the world of a very atypical Victorian family. It’s a world where avant-garde fashion meets female liberation, drug addiction, political radicalism, and wombats.

More like this:

– The tragedy of art’s greatest supermodel

– 10 artworks that caused a scandal

– The 300-year-old pet portraits

“The Rossettis were into anything strange and extreme,” Carol Jacobi, the curator of the exhibition, tells BBC Culture. “They were very impatient with the conventional rules of art and literature. They were looking around for alternative heroes: they were Britain’s first avant-garde art movement.”

For some, the paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the movement he co-founded) are too punctilious and primly moralising, especially when compared to contemporary French art movements like the Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists, with their bolder formal experiments and franker depiction of modern life. But that misses the most important aspect of the Rossetti generation in Britain. Their major contribution was a radical new attitude for artists and female creatives in the country – “bohemianism”.

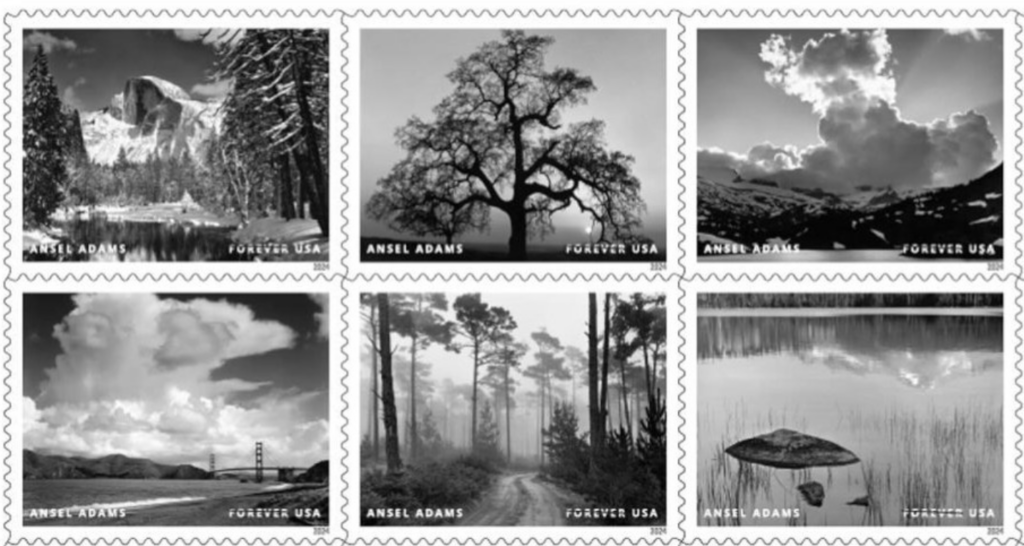

The white poppy in Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix, 1864 symbolises the death of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, who overdosed on laudanum in 1862 (Credit: Tate / Baroness Mount-Temple)

Originating as a derogatory term for Roma travellers in France, the term has since been used to define individuals of unconventional behaviour and experimental fashion choices: those who mischief the rules of society and soar towards adventure, and expressive freedoms. The bohemian spirit of outlandish fashion and excessive behaviour is central to modern-day music, design, clothing, and art. Its counter-cultural swagger is integral to the devil-may-care attitude of performers like Patti Smith and the 1975’s Matty Healy, the outré fashion of David Bowie and Lady Gaga, and the hedonism of Keith Richards and Kate Moss. At its heart, bohemianism is an assault on any value perceived to be middle-class. That involves conventional gender roles, conservative attitudes towards love, traditional family values, conformity in dress, and the repression of sensual pleasure.

How did the Rossettis kick-start this influential way of life among artists back in Victorian Britain? And how do wombats come into the picture? It begins with the unconventional family household. The Rossettis were first-generation Londoners: their father was an Italian freedom-fighter and poet, and their mother was a scholar, also from an Italian family. The young Rossettis were brought up in a unique environment where progressive politics and artistic creativity were of the highest value.

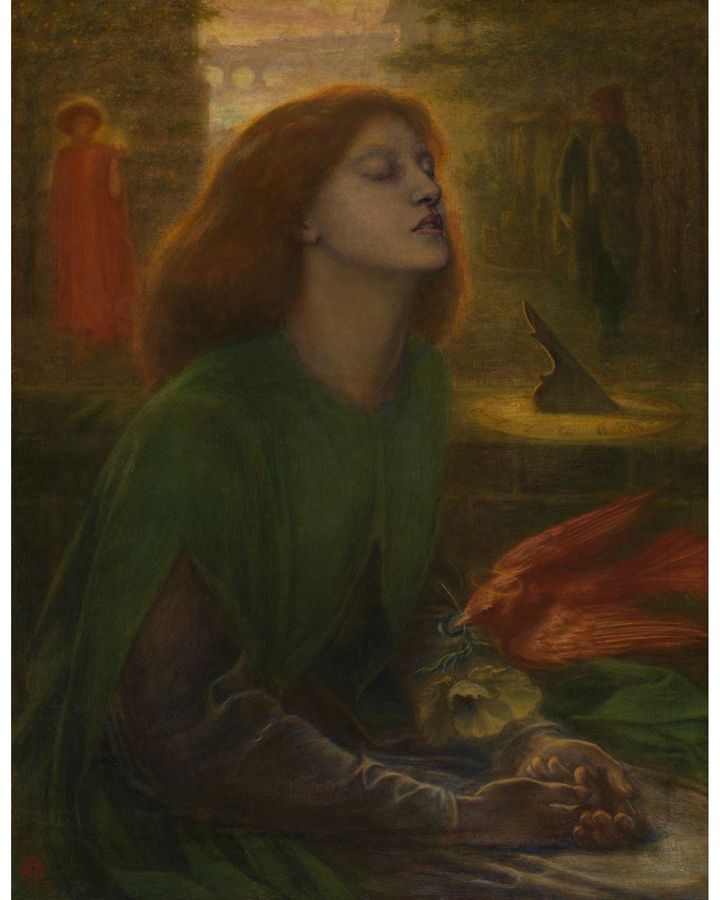

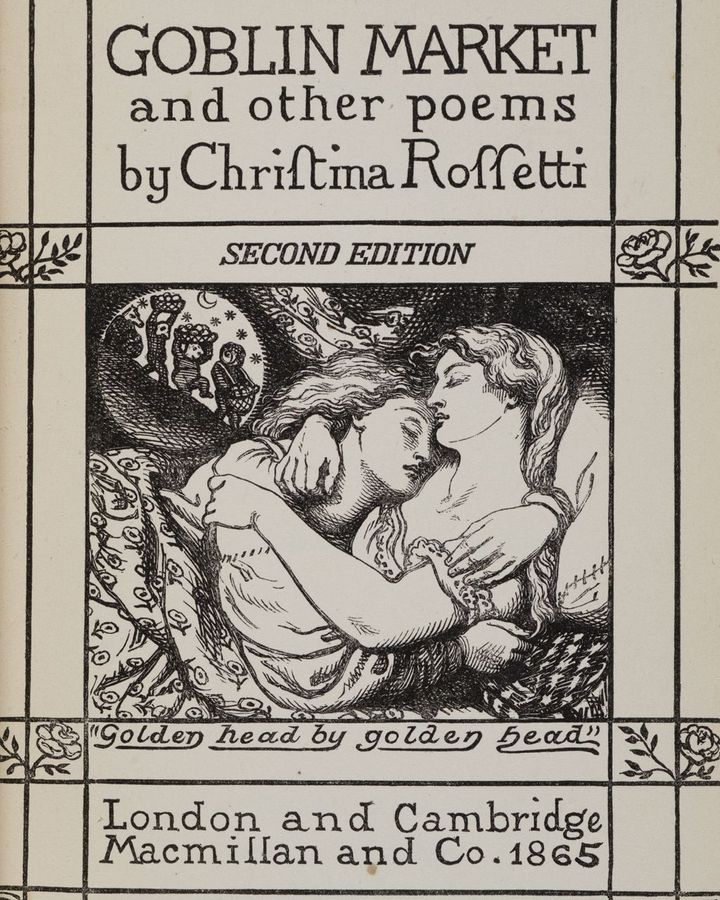

Christina Rossetti’s poetry was first published when she was 16 years old; her best-known work is Goblin Market (Credit: Tate)

Christina Rossetti (1830-1894) blazed an early trail – her poetry was first published when she was just 16 years old. Probably her best-known poem is Goblin Market (written in 1859), a startlingly original allegory of sexuality corrupted in a materialist world. These themes would later be mirrored in Gabriel’s and Elizabeth’s paintings. Christina was a quiet radical, leading an unconventional life for a woman at the time. She established a highly successful and well-remunerated career without the bourgeois dependence upon a husband as financial guardian.

‘Rock ‘n’ roll excesses’

If you’re still wondering about the wombats, they are relevant to Christina’s brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). He was equally precocious, co-founding a revolutionary new art movement, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, aged 20. The “PRB” was dedicated to bucking the authority of Britain’s Royal Academy of Arts. It believed in an art that offered truth based on perceptual accuracy and moral courage, both of which Gabriel believed to be lacking in academic art favoured by the middle classes. He led his artistic contemporaries with charisma, inspiration, and a revolutionary outlook which could be tantalisingly bizarre and often bordering on the scandalous.

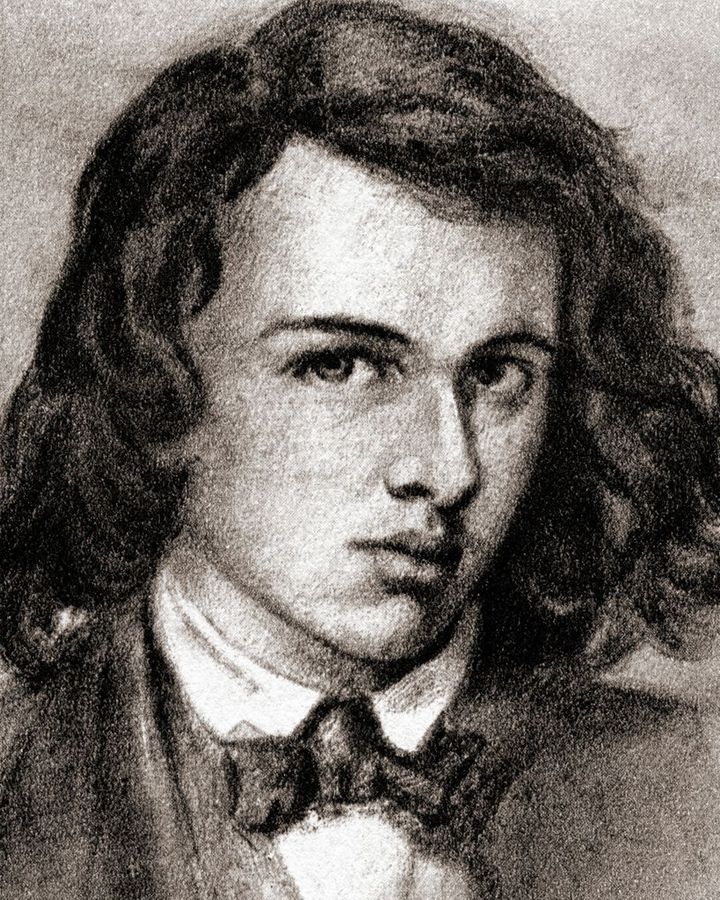

Dante Gabriel Rossetti co-founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which was dedicated to challenging the authority of the Royal Academy (Credit: Alamy)

“Gabriel dropped out of art school – you don’t get much more bohemian than that,” Carol Jacobi explains. “He would wear evening dress during the day, and he was the first of these people who would go around wearing black to be cool.”

In his attitude towards love, Gabriel probably saw himself as a boundary-pushing libertine. But his liaisons were also mindless of anyone’s emotions but his own. Whilst in a long-term relationship with Elizabeth Siddal (which lasted 10 years before he proposed marriage) Gabriel had a tryst with Fanny Cornforth, a popular Pre-Raphaelite model. He later had an affair with Jane Morris, wife of his friend William Morris.

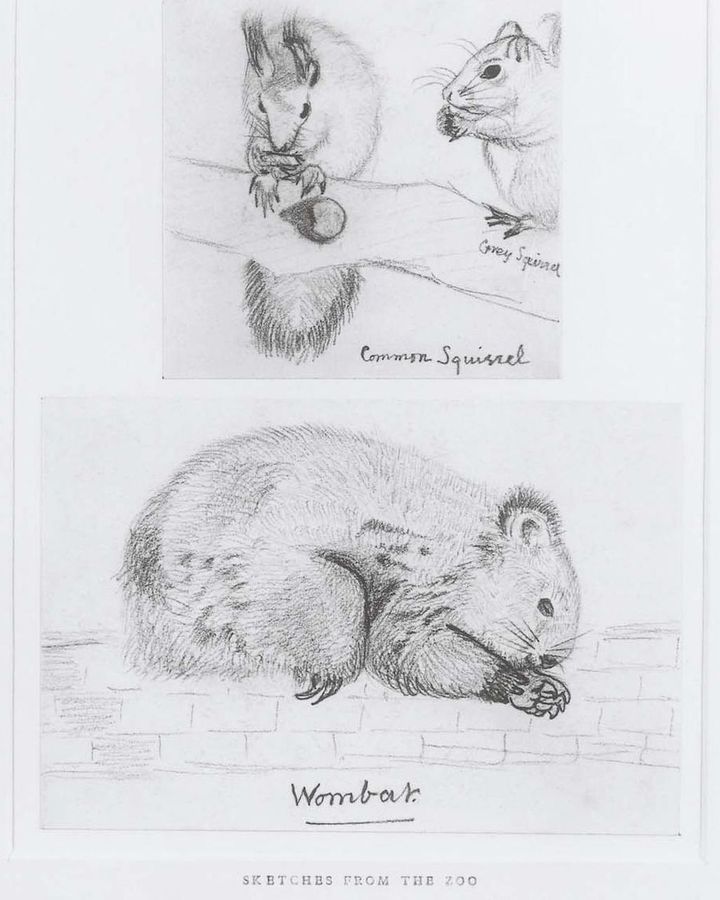

A wombat in Three Animals Studies by Christina Rossetti, one of the many exotic pets kept by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in his Cheyne Walk residence (Credit: Alamy)

After Siddal died in 1862, Gabriel moved into a house in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. It became host to his rock ‘n’ roll excesses, particularly his obsession with exotic pets. Wombats were a particular fixation, but he also kept an armadillo, peacocks, kangaroos, a mole, and a Pomeranian hound named Punch. His pet toucan was taught to ride around the house on a llama. These animals frequently ran amok in the household or escaped to terrorise Gabriel’s respectable neighbours. According to the US painter Whistler, late one night Gabriel had his wombat brought to the table along with coffee and cigars, so that it could enjoy readings by another guest, the scandalous poet Algernon Charles Swinburne.

Triumph and tragedy

These stories bring out key aspects of the bohemian character – a disdain for bourgeois norms, a penchant for self-mythologising, and perhaps the most influential, the idea that art didn’t have to be boxed in a gallery or museum. For Gabriel, life itself became a kind of art form. Gabriel’s excesses reached new depths in 1869, when he exhumed the corpse of Siddal from her grave in Highgate Cemetery to retrieve a manuscript of poems that he had placed beneath her hair. The pages had to be soaked in disinfectant for two weeks before Gabriel could transcribe them for publication. Like Siddal, Gabriel was to die relatively young in 1882, from addictions to alcohol and chloral hydrate, a medically prescribed sedative.

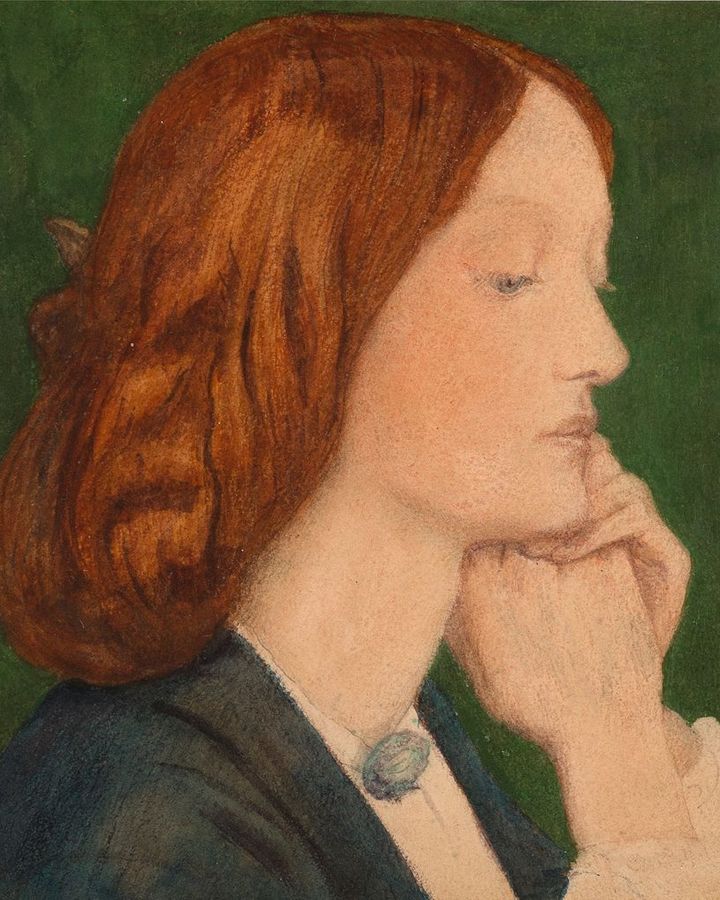

Elizabeth Siddal (1829-1862), Gabriel’s lover and eventual wife, was a pioneering woman of the 19th Century, devising her own unconventional and self-made fashions, and establishing independence as an artist. “She completely redefined women’s clothing,” says Jacobi. “She just couldn’t be doing with crinoline and corsets and all that stuff, so what she did was to redesign working clothes. She went out in adapted fashions with her hair down. That freedom of clothing was so inspirational. It became the look – if you wanted to see yourself as a progressive young woman, that’s how you would dress.”

Elizabeth Siddal, c1854 – Siddal worked in a hat shop before being befriended by the Pre-Raphaelite artists, often serving as their model (Credit: Delaware Arts Museum)

Siddal was a working-class woman who was employed in a hat shop before being befriended by Pre-Raphaelite artists in 1849. She served as a model in their paintings, and then became an artist in her own right. Gabriel and Elizabeth collaborated and influenced each other. Their love affair and eventual marriage was tumultuous and problematic and has since become much mythologised. But there are aspects to her bohemian character that come through strongly in her story.

“She very much didn’t lead her life according to the rules,” Jacobi explains. “She spent years with Rossetti before they were married, and recently it’s been suggested that it wasn’t the case that she was waiting for Gabriel to marry her, but she was deliberately retaining her independence.”

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal as Lady Affixing Pennant to a Knight’s Spear, 1856 shows the recurring theme of love in the Rossettis’ art and poetry (Credit: Tate)

Siddall was essentially self-taught, she defied social categorisation, and wore liberation as a badge of pride. These characteristics were innovative in Victorian London but became the very definition of bohemianism in the next century and beyond. Tragically, like Gabriel, Elizabeth was a victim of addiction: she died from an overdose of laudanum, an opioid that was used as a painkiller in the 19th Century.

The Rossettis’ story contains as much triumph as it does tragedy. But their greatest gift to art history (bequeathed in three very distinct life stories) was to invent Britain’s first artistic subculture, lived in direct conflict with Victorian standards. Christina busted gender stereotypes about female creativity, love, and family life; Gabriel flouted bourgeois norms of every stripe and made daily life an artistic event; and Siddal established a unique creative and sartorial independence. Rather than living the lifestyles dictated by society, they chose their own path – and they became Britain’s original arty bohemians.

The Rossettis is at Tate Britain, London, until 24 September 2023.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

;