Growing and processing cassava isn’t hard!

Inside the continental US, cassava is generally unknown to gardeners, other than immigrants from warmer climates who grow some on a backyard scale.

Yet it’s where tapioca comes from (or “fish eyes,” as my Uncle Stuart calls them) and has been used as a source of laundry starch.

The roots are really, really high in starch.

Growing to about 12’ tall, the cassava plant looks very tropical.

Its palmate leaves and graceful cane-like branches are attractive in the landscape or in the garden. Cassava’s pseudonyms include yuca (with one “c,” NOT two – “yucca” is a completely unrelated species), manioc, the tapioca plant, and manihot.

In Latin, it’s Manihot escuelenta.

Whatever you call it, it’s a serious staple crop. Virtually pest-free, drought tolerant, loaded with calories, capable of good growth in poor soil – cassava is a must-have anyplace it can grow. And it’s MUCH less work than grain and much more tolerant of harvest times. In fact, once it’s hit maturity, you can basically dig it at any point for a few years (though the roots may sometimes get too woody to eat).

But there is a caveat on cultivation: cassava doesn’t like cold. At all.

If temperatures drop to freezing, your cassava will freeze to the ground.

This won’t usually kill the plant, but it does mean you need to plan your growing accordingly. In the tropics, cassava is a perennial, capable of growing huge roots and living for years.

If you live north of USDA Growing Zone 10, then the occasional frosts will knock it down. Growing it at any zone beyond 8 may be an exercise in futility. Cassava needs warm days and nights to make good roots.

And speaking of roots… the cassava’s roots contain roughly twice the calories of a comparable serving of potatoes.

Bonus: they’re easier to grow.

Of course, there is the cyanide to consider.

CYANIDE?

What – you didn’t think a plant this awesome could exist without a down side, did you?

Yes – cyanide.

The plant contains a certain amount of it, from its lovely leaves to its tasty roots. Fortunately, boiling or fermenting gets it out, so fear not.

A lot of plants we eat are poisonous. Just google the “cashew tree” or look up the toxicity of dry kidney beans.

Now THAT’S scary.

Compared to many things we eat, cassava’s pretty tame.

Microwaveable burritos, for instance.

Sweet and Bitter Cassava

That said, there are “sweet” varieties and “bitter” varieties of cassava. Sweet types are low in cyanide and are safe to eat after cooking to fork-tender, but bitter types are high in it and need additional processing. You’re unlikely to get the high-cyanide varieties in the US, but it’s good to know they exist. I don’t have any “bitter” types in my garden, and have not seen them, even when I lived in the Caribbean where cassava cultivation is common.

All we do to make our cassava safe to eat is to cook it until it’s soft, but that’s because it’s a “sweet” type.

The bitterness of a cassava root usually correlates to its cyanide toxicity. As a study from Africa posted on the National Library of Medicine notes:

“Farmers in Africa generally use the bitter taste of cassava roots to perceive the potential toxicity of cassava [13,18,19]. Research has shown that a greater portion of cassava varieties perceived as bitter and toxic by farmers, do indeed contain higher cyanogenic glucoside levels than cassava varieties perceived as being sweet [18]. However, this may not always be the case, as cassava contains other bitter compounds [20], making validation necessary. However, during a period in which a konzo epidemic was experienced, families had been reported to complain that cassava roots were more bitter than normal during that period [21]. Thus, through taste perceptions, most people had become conscious of an increase in cassava root bitterness that led to cases of cassava cyanide intoxication. This report shows that the bitter taste of cassava roots can be used to determine increased root toxicity. Cassava root taste can also be used to assess changes in the degree of bitterness in roots of a particular cassava variety [22,23].”

Low rainfall and tough growing conditions tend to make roots more toxic. The takeaway here is that if your cassava roots taste bitter, they’re probably not good to eat.

That said, over a half-billion people eat cassava on a regular basis and manage to live just fine through it, so don’t get too hung up. Get sweet varieties and take care of them, and cook them well. You can also soak cassava roots for a few days before cooking to make them even safer, though we don’t bother doing that with our roots.

How to Grow Cassava

Now – moving beyond the cyanide – how do you grow these things?

Unlike many plants, cassava is not usually grown from seeds except for breeding purposes. The only way most folks grow it is via stem cuttings.

Roots from the grocery store almost definitely won’t work since they’ve been separated from the stem and dipped in wax, so it’s important to get cuttings somewhere. Grower Jim in Orlando sometimes has them, as does Josh Jamison at Cody Cove Farm. You’ll also find cassava cane cuttings for sale on ebay and Etsy.

Or you can make friends with people at your local gardening group and see if any of them have it. If you live in a warm climate, chances are good.

Planting Cassava

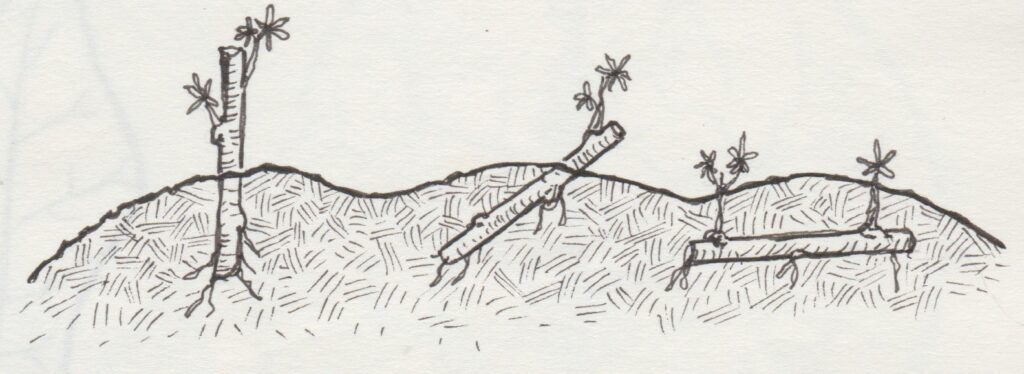

To grow from fresh cuttings, chop a sturdy stem into pieces about 1.5’ long and stick them in the ground on their sides about two inches down and cover them lightly with soil. Select cuttings that have gotten woody, with bark that is no longer young and green. Within a week or so they’ll be growing new leaves. You can also plant the canes vertically, about 2/3 in the the ground, or even diagonally. Some farmers claim diagonal planting is even better than vertical.

However I plant them, I get roots, but at some point I need to do a side-by-side comparison of planting techniques.

Cassava likes irrigation and good soil, but isn’t too picky. It will survive drought and heat. 6-12 months later (depending on variety, care and rainfall), they’ll be ready to start harvesting.

Harvesting Cassava

To harvest, machete down the entire plant a foot or so from the ground, throw the branches to the side and start digging.

Be careful, though – the roots are easy to chop through. Some careful exploratory digging with a trowel is often a good idea. The roots you’re looking for grow down and away from the main stem and are generally located in the first 1-2’ of soil. They’re deep brown with flaky skin. Don’t dig them too long before you’re going to process them as cassava doesn’t store well at all.

Once you harvest the roots, you’ll want to chop up the rest of the plant to make a new set of canes for planting out. I snap off all the leaves and compost them, then cut the bare canes into planting size.

Saving Cassava Cuttings and Planting Them

Remember: canes that are too green tend to rot rather than root, so throw them on the compost too.

Sturdy, 1-2” diameter canes are perfect.

Plant them a third of their length or so into the ground and stand back so the new growth doesn’t knock you over. Just don’t plant them upside-down.

Ensure they’re right side up by looking for the tiny little growth buds by the leaf bases (or where the leaves were before they hit the compost bin). That little dot should be above the leaf’s base, not below.

The Cassava plant is a must-have in warm climates, but even at the edge of its natural range you can push it.

Keeping Cassava Alive Through Winter

You can bury cut canes in a box beneath the ground for the winter, as a Cuban friend told me her family does… you can let your current plants freeze to the ground and just wait for spring to bring new growth back… you can put cuttings in pots and bring them inside on freezing nights, then plant out in spring… or you can get a greenhouse and always keep a few plants in there for propagative stock.

It’s pretty tough stuff. And as for work, the worst part is the harvesting.

View it like digging for treasure and it’s fun.

Cassava Leaves are Edible

Another great thing about this plant: its leaves are also edible (boiled, of course – remember… CYANIDE!) and rich in nutrients. The young leaves are best and remind me of a drier-tasting collard green. I generally compost them, as I have plenty of other greens I prefer, but they are worth eating if you like them.

Storing Cassava Roots

The roots can be chopped and frozen – they keep quite well that way. You can also dry them into flour. Or, do what I do, and try not to harvest cassava until we’re going to eat it! Roots keep very well in the ground.

They just need to be peeled first. There is an easy-to-remove peel that simply requires slitting and pulling to remove. It’s more like bark than a proper “peel.”

These are roots I grew in Alabama, USDA zone 8:

We’re beyond the tropics, yet some varieties of cassava are still doing well for us.

Here are what the roots look like peeled:

Cassava is literally a lifesaving staple in Africa, and can be the same in zones 8 and warmer.

If you want to learn more about this and many other survival crops, check out my book Florida Survival Gardening and Grow or Die.

David The Good

Source link