When Tom Johnson decided to write a memoir, he sent the first draft to his friend Bill Moyers. They had worked together during the 1960s when Johnson was a White House fellow and Moyers was press secretary to President Lyndon B. Johnson. It was Moyers—once Billy Don Moyers of Marshall, Texas—who suggested that Tommy Johnson of Macon, Georgia, become Tom. Sounded more serious. After their stints in government, both went on to exemplary careers in the media: Moyers as a public television eminence and Johnson as publisher of the Los Angeles Times and then president of CNN during its prime.

After reviewing the manuscript, Moyers sent Johnson a blunt suggestion: “You need to get yourself an editor.”

Johnson felt stung.

“I’ve always thought of myself as a decent writer,” he says. “But Bill was right. It’s like I was writing a book about this character named Tom Johnson. I’ve always reported on other people. It’s hard writing about yourself.”

Courtesy of The University of Georgia Press

Twenty-six drafts and years of worry later, Johnson’s memoir, Driven: A Life in Public Service and Journalism from LBJ to CNN, has been published. The only blurb on the cover comes from Moyers, who died last summer. “President Johnson invested more confidence in the young man from Georgia and Harvard than he did in anyone else on his White House staff,” it begins.

The young man is 84 now and busily curating a life spent working for and covering the powerful.

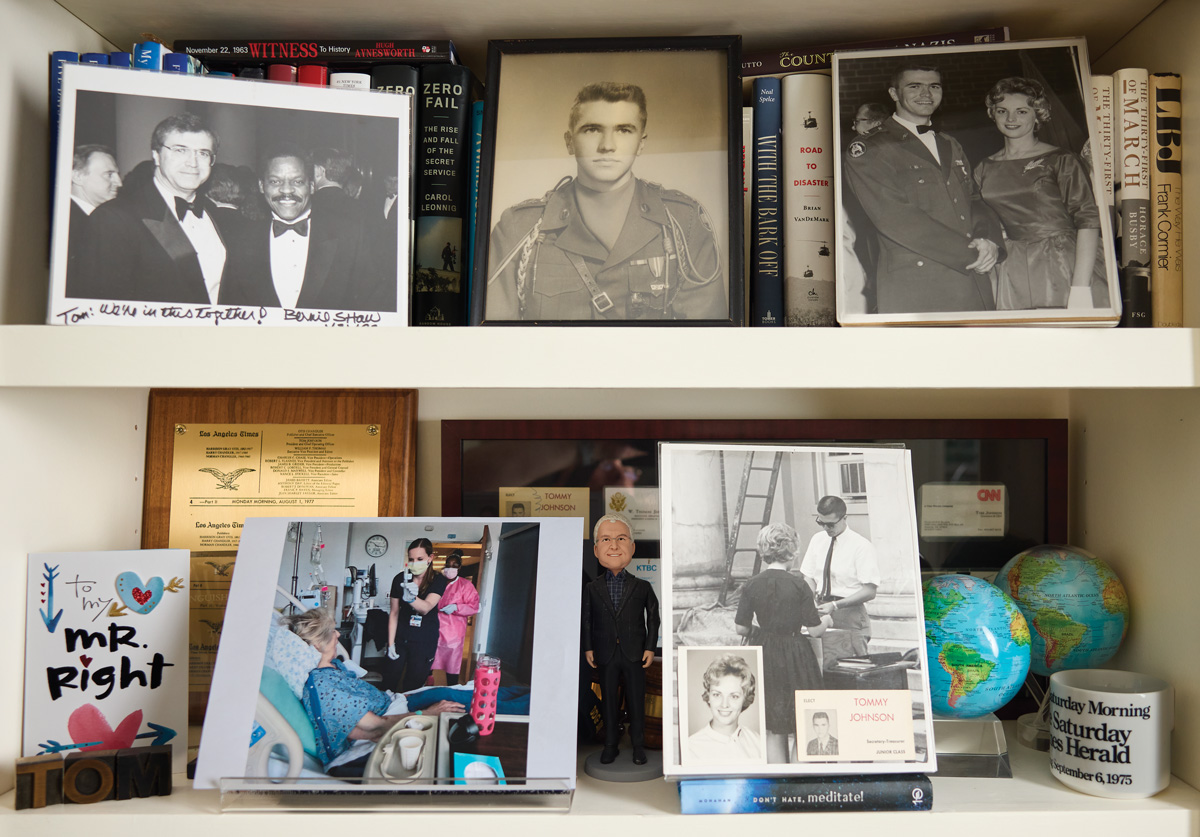

“Let me show you something,” Johnson says, bounding off mid-interview into the garage of his home overlooking a wooded ravine and gurgling stream in Buckhead. He’s a big man bursting with energy and purpose who speaks with an authoritative drawl. He pulls back a curtain where a third car used to be parked and unveils a personal archive full of boxes relating to LBJ, Ted Turner, and other notable, complicated leaders he has worked with.

“I have been in the room in so many situations,” he says. “I just hope people don’t think I’m a name-dropper or a narcissist.”

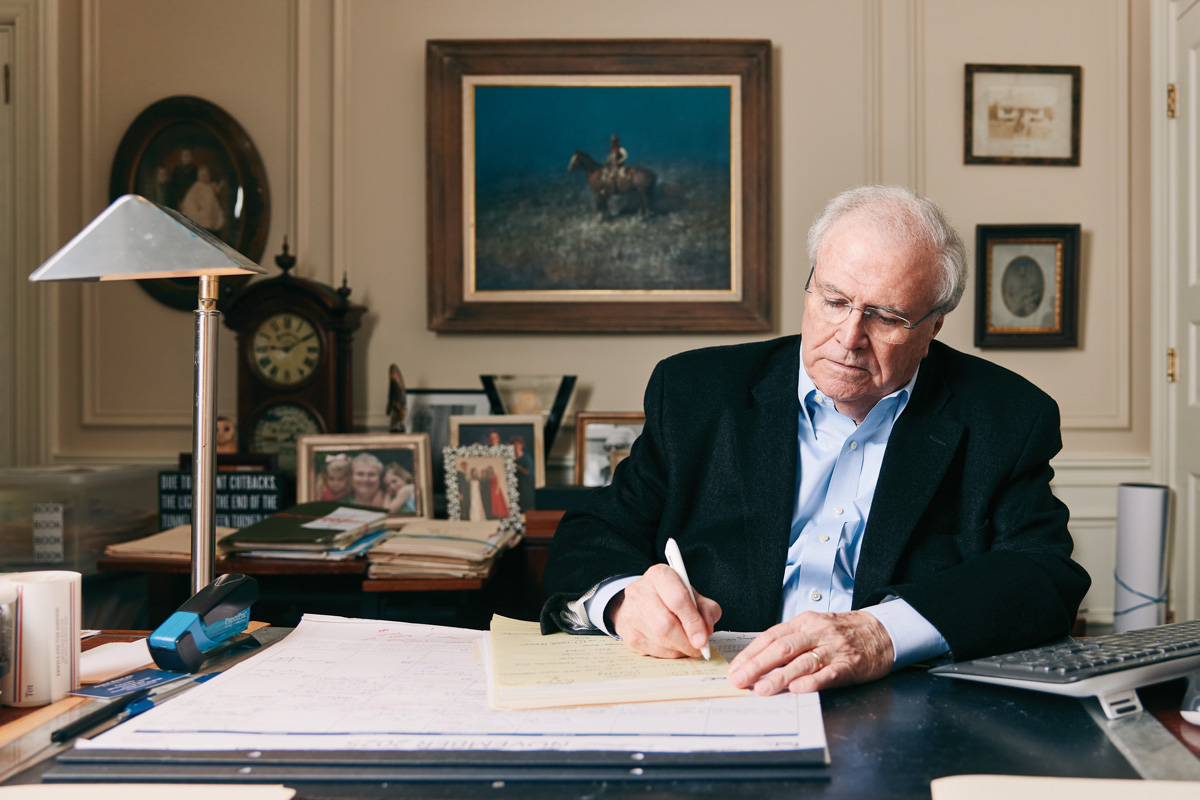

Back in his study, where he pulls out files of correspondence with labels like “Nixon,” “Carter,” “Reagan,” “Bush,” and “Clinton,” he points out a sheet of paper taped to the closet door. It’s a distillation of his book, expressed in a kind of meaning-of-life epigram:

The Story of a Boy

From Georgia and his

Nearly Fanatical Drive

“To Make It”

The Good That He Did

And the price he paid to do it.

It took Johnson more than half of his life to recognize what that last part meant.

Photography by Ben Rollins

The story begins with one of those boxes in the garage, one labeled “Jo-Jo’s Books and Bibles.”

That would be his mother, Josephine, a bright woman whom Johnson credits with inspiring in him a quenchless curiosity and drive. He loved his chain-smoking father, Wyatt, but he didn’t regard him as a role model since he had a third-grade education and never held a full-time job during Tommy’s childhood.

“He embarrassed me,” Johnson admits. “I used to have him drop me off a block from school.”

The Johnsons didn’t have much money. Tommy worked from an early age, bagging groceries and pumping gas at a store owned by an uncle. Then he found his calling at the precocious age of 14 when he started covering sports for the local paper, the Macon Telegraph. He still has his first press card.

Johnson impressed everyone at the paper. One day the owner, Peyton Anderson, called him into his office and offered to pay his way to the University of Georgia if he studied journalism and promised to keep working for the Telegraph.

Johnson was a ball of fire in Athens. He joined the student newspaper, the Red & Black, and helped cover the desegregation of the university, walking alongside Charlayne Hunter—one of the first two Black students to enroll—as someone spit at her and protesters chanted “two, four, six, eight, we ain’t going to integrate.” She later worked for him as a CNN bureau chief in South Africa.

On weekends, Johnson raced home from Athens and wrote for the Telegraph. Somehow he found time to become president of his fraternity and get elected to class office. Which is how he met his wife, Edwina Chastain, a former basketball player who had recently broken up with an all-SEC lineman for the Bulldogs, Pat Dye, who went on to become a legendary coach at Auburn.

Photography by Ben Rollins

Johnson pulls a framed photo from a study shelf. It’s a Red & Black image of a blond Edwina and a flat-topped Tommy at a polling station during class elections. “How many couples can say they have a photo of the moment they met?”

Naturally, he proposed in the student newspaper office—a hint of things to come.

Although Johnson loved reporting, he was more interested in becoming a publisher. Anderson again invested in him, offering to pay his tuition at Harvard if he could get accepted to its Master of Business Administration program. He did, and the couple, then married, headed to Boston. As he was finishing his master’s degree, Edwina heard about a new White House fellowship program and urged him to apply. He beat out the future Elizabeth Dole for one of the last slots.

Johnson had every intention of returning to Macon to launch his journalism career and repay Anderson’s generosity, but he never quite made it back.

He’ll be there eventually. After his father died many years ago, Johnson took ownership of the modest house where he grew up, for purely sentimental reasons. When he dies, he has requested that part of his ashes be scattered in the back yard where his boyhood dog, Sparky, is buried.

On Johnson’s first day at the White House, Moyers said he wanted to introduce him to some people and surprised him by walking him straight into the Oval Office to meet the president. LBJ took a shine to the young man.

“I think he saw something of himself in Tom, as he had with Bill,” says Larry Temple, who later served as White House counsel and now heads the LBJ Foundation, succeeding . . . Tom Johnson. “They were like surrogate sons to him.”

One of Johnson’s assignments was to take notes at a lunch meeting LBJ held every Tuesday with a small group of his closest advisers. Years before Johnson started writing his memoir, he petitioned the National Archives to declassify some of his notes, which contained top secret information. “It’s a slow and thorough process,” he says. “It took 20 years, and there’s still parts redacted.”

The most sensitive notes came from two sessions about nuclear weapons, initiatives given code names worthy of a ’60s spy novel: Furtherance and Fracture Jaw. Furtherance was a recommendation to change the U.S. nuclear release protocol, which, shockingly, had called for attacking China and the Soviet Union simultaneously in the event of a nuclear strike by either that killed the president. Fracture Jaw involved planning for tactical nuclear weapons to be used against the North Vietnamese to relieve the siege of Khe Sanh during the 1968 Tet Offensive.

Johnson took minutes at both meetings, astonished by what he was hearing. “I’m still not sure they should have let me release any details about our nuclear policy,” he says.

The subject that dominated many of the lunches was LBJ’s albatross, Vietnam. Before he worked at the White House, Johnson was an ROTC officer at UGA preparing for active duty in the Army. But he was injured during a parachute-training accident at Fort Benning and required surgery for a hernia. “Best piece of bad luck I ever had,” he says. “I still have the scar.”

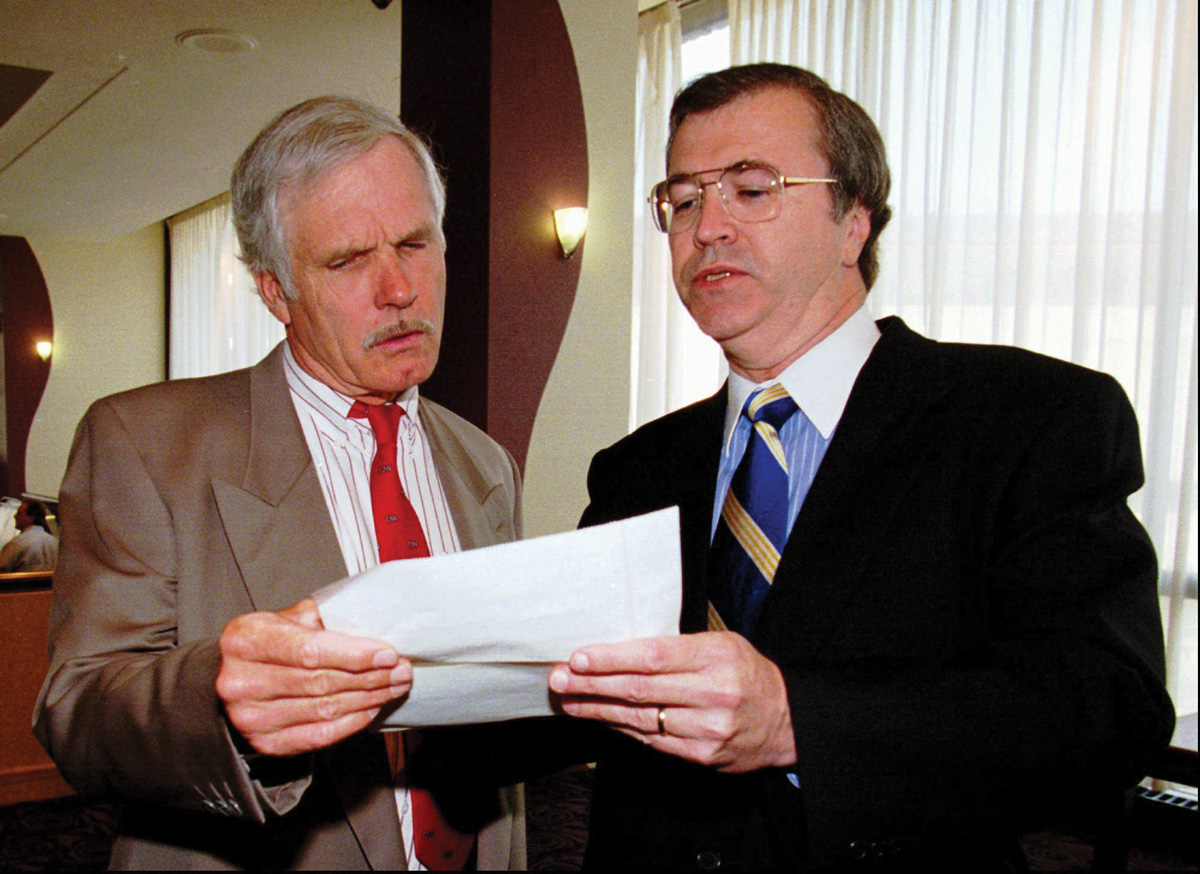

Courtesy of AP Photo/ Charles Tasnadi

As he sat in West Wing meetings listening to LBJ, Robert McNamara, and Dean Rusk discuss body counts and political dominos, Johnson never really questioned the wisdom of the war. Some of his former classmates were serving in Vietnam and writing him letters saying that things weren’t going well, and Johnson even shared some of them with the president. But he was so loyal to LBJ that he supported his Vietnam policy the whole time.

“It was a catastrophic mistake,” he now says. “I sat around a table no bigger than this”—he gestures toward his kitchen table—“and was so focused on taking accurate notes that I didn’t really hear what they were saying.” He admits to feelings of guilt.

Soon after LBJ decided not to run for reelection, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and dozens of cities ignited in violence. Johnson was one of the few people in the helicopter with the president as he flew over Washington to witness the angry fires and boiling smoke. “It was almost completely silent except for the sound of the chopper blades,” he remembers. “He was just watching, absorbing the impact.”

After LBJ left Washington, Johnson followed him to Texas and worked as his aide for several years. He could see the former president’s health decline—he gobbled nitroglycerin pills for his heart disease—and figured his time was short.

Once, when LBJ was hospitalized and Johnson was at his side, the president realized his aide had missed an important family event, and sent a handwritten letter to his wife. “Edwina dear,” it begins. “I’m a mean old man, who else would take your man away on your birthday? I’m sorry.”

“Lyndon Johnson was a complicated man who could be loving and generous and mean and crude,” Johnson says. “I still feel a loyalty to him.”

Johnson left LBJ’s family company in the mid-1970s and returned to journalism, taking a job offer from Otis Chandler, head of Times Mirror, a newspaper company that published one of the best and most profitable papers in the nation, the Los Angeles Times. After a stint running the Dallas Times Herald, Johnson moved to L.A., where Chandler anointed him his successor as publisher—the first person outside the family to run the Chandler empire.

Courtesy of UCLA Library Special Collections

During the 1980s, Johnson was one of the most important people in Southern California, a media prince in a town renowned for media. But it all came apart at the end of the decade after Chandler retired and other family members took control of the company. In 1989, they ousted Johnson. Suddenly, nearing 50, he needed a job.

Johnson had many prospects. One he was very interested in was to head Cox Enterprises, the company that publishes the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, but that courtship didn’t quite work out. It was just as well. His dream job materialized in 1990 when Ted Turner asked whether he might like to run CNN.

The job offer came in memorable fashion. Turner and his then wife, Jane Fonda, joined the Johnsons for dinner in L.A., but Tom was suffering from a sudden stomach bug and had to excuse himself repeatedly to go to the restroom and throw up. The four of them left in the same car, and Johnson asked the driver to pull the car over so he could get out and barf again. While Johnson was sitting on the side of the Pacific Coast Highway recovering, Turner rolled down a window and said, “If you still want the job, you’ve got it!”

One of Johnson’s friends, Don Rountree, a veteran public relations man who had roomed with him in college, picked the Johnsons up at the Atlanta airport when they arrived to start their new life. To Rountree’s surprise, Johnson asked to be taken directly to CNN Center. “It was after dark, but Tom didn’t want to wait until the next day. He was ready to go,” Rountree says. “The guard didn’t know who he was.”

There was a lot going on. Iraqi forces had just invaded Kuwait, and Johnson had to learn cable TV on the fly as CNN responded to one of the biggest news events of its young existence. Six months later, when the U.S. launched Operation Desert Storm against Saddam Hussein, CNN had perhaps its finest hour when it managed to keep Bernard Shaw and other correspondents in Baghdad to report live on the bombardment. President George H.W. Bush and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell both phoned Johnson, and Powell told him to “get your asses out of Baghdad.”

After consulting Turner, Johnson ultimately declined. He says, “Ted said to me in the loudest voice, ‘Our decision is that those who wish to stay should stay. Those who want to leave can leave. And you will not overturn me, pal.’”

Eason Jordan, then CNN’s international editor and now an executive with The Rockefeller Foundation, notes that it was a different time for the media. “This was well before Fox News and MSNBC,” he says. “There was no social media and no internet to speak of. We were working all the angles, talking to the Iraqi government, setting up the technology, trying to get the right people in the right places so we could get coverage out of Baghdad.”

Johnson regards CNN as the best and most exciting job of his life. The good times lasted about a decade. In 1996, Turner sold the network to Time Warner in a move designed to give the operation greater resources and impact. Johnson had reported directly to Turner and hated for that to end, but he remained optimistic. Not so with the next deal, in 2000, when Time Warner merged with AOL in a combination that proved disastrous for all.

“I knew things had changed when they called me into the office and asked me why we weren’t broadcasting live from the scene where a man was threatening to jump from a crane,” he says. “I told them that was tabloid journalism, and I didn’t want to do it.”

Courtesy of AP Photo/Ric Feld

CNN could have taken different paths during Johnson’s tenure. Years before Fox News was born in 1996, Turner had the idea of starting a conservative news channel. “I explored it, but I thought it would be difficult for me to oversee that,” Johnson says. “CNN was an independent channel, and this would be designed to appeal to conservative voters. I even called Rush Limbaugh. Ted had been warned that Rupert Murdoch would start a conservative channel. Rupert and his allies certainly saw that as a niche.”

Johnson remembers another intriguing what-if that he and Turner considered at the time. Rummaging through the file boxes in his garage, he fishes out a memo he wrote to Turner in 1998 discussing the possibility of Turner running for president. “He actually considered it,” Johnson says.

By 2001, Johnson was no longer enjoying CNN. He became depressed, and his wife noticed that he didn’t seem happy leaving for work anymore, which was not like him. One day that summer, dining alone at a family restaurant in Macon, he saw a blank paper place mat with crayons intended for children. He put them to an adult purpose, listing the pros and cons of retiring from CNN in block letters of green.

“I’ve still got it,” Johnson says, unfolding the place mat on his study desk.

The last argument for retiring— “Meaningful Life?”—seemed prophetic.

Johnson’s despair over what was happening at CNN was not the first time he had shown signs of depression. He had been addicted to work since his teens and admits that he was a distant husband and father who sometimes lashed out at his wife and their children, Wyatt and Christa. His mental health issues became apparent in the late ’80s when his perch atop the Los Angeles Times was kicked out from under him.

“He’s always been so serious,” Edwina Johnson says.

She tells a story about how she used to like to wake up, open the blinds to let in sunshine, and turn on music. Her husband did not appreciate this display of morning cheer. One day, she says, he looked at her and said, “Edwina, life’s not one big smile and one long song.”

Another time, trying to figure out what was wrong with him, she saw a Today Show segment about male menopause and decided that must be it. She bought a book on the subject, but when Tom saw the title, he threw it across the room and said, “There’s nothing wrong with me.”

Finally, she insisted he see a psychiatrist at UCLA. The diagnosis: chronic depression. Johnson eventually embraced the doctor’s recommendations, started therapy, and tried different medications until he found an antidepressant that worked for him.

After the Johnsons moved to Atlanta, he befriended Larry Gellerstedt and J.B. Fuqua, respected businessmen who had suffered from depression for decades and talked about it publicly. Soon Johnson went public too.

Courtesy of AP Photo/Dennis Cook

In 2004, he moderated a panel of famous friends—novelist William Styron, humorist Art Buchwald, and journalist Mike Wallace—to discuss their depression struggles at Skyland Trail, a treatment center in Atlanta. They billed it as “An Evening with the Blues Brothers.” Johnson has been involved with Skyland Trail ever since. “He’s an amazing fundraiser, incredibly tenacious and persistent,” says J. Rex Fuqua, J.B.’s son, for whom Skyland Trail’s adolescent campus is named. “It’s hard to say no to Tom.”

In his retirement, Johnson has branched out to other causes, each because of a trauma that struck close to home.

He raises money for addiction treatment because substance abuse often intertwines with depression. He saw the problem firsthand when Cope Moyers, the son of his mentor Bill Moyers, went on a crack cocaine bender in Atlanta while he was employed at CNN. Moyers got straightened out and now works with the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.

Johnson also raises money to fight Alzheimer’s disease. His daughter has a rare form of the disease, called posterior cortical atrophy, which degrades visual perception, spatial awareness, and motor skills.

His latest cause is cancer research. A few years ago, Edwina was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, and she’s been undergoing experimental cell treatments at the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Johnson takes these commitments seriously. “He’s focused on what he calls his ‘eighth inning,’” says Edward “Jack” Hardin, a lawyer who worked with Johnson to create the Addiction Alliance of Georgia. “He wants to be as effective in social issues as he was in business, and I admire him for that.”

In addition to fundraising, Johnson volunteers with various organizations and spends hours on the phone speaking with people who need treatment referrals or just someone to talk to. He remembers one man who told him he was considering suicide. Johnson, who had once had suicidal thoughts himself, knew the man had a beloved pet, so he posed a question: “Who’s going to take care of the dog?” Simply thinking about that, the man later told him, made him reconsider.

Photography by Ben Rollins

Of all the things Johnson has done in his eventful life and career, writing a memoir about it all was one of the most difficult. “It was as hard as getting an MBA at Harvard,” he says.

Edwina saw how much her spouse struggled for years to get everything down exactly as he wanted to. She says, “The stress that he’s gone through with this book—he is not writing another one with this wife.”

This article appears in our January 2026 issue.

Advertisement

Jim Auchmutey

Source link