CNN

—

The crushing demand for AI has also revealed the limits of the global supply chain for powerful chips used to develop and field AI models.

The continuing chip crunch has affected businesses large and small, including some of the AI industry’s leading platforms and may not meaningfully improve for at least a year or more, according to industry analysts.

The latest sign of a potentially extended shortage in AI chips came in Microsoft’s annual report recently. The report identifies, for the first time, the availability of graphics processing units (GPUs) as a possible risk factor for investors.

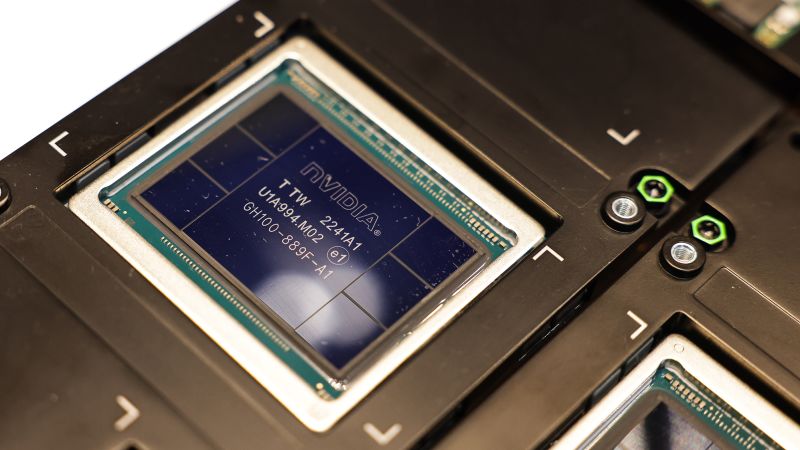

GPUs are a critical type of hardware that helps run the countless calculations involved in training and deploying artificial intelligence algorithms.

“We continue to identify and evaluate opportunities to expand our datacenter locations and increase our server capacity to meet the evolving needs of our customers, particularly given the growing demand for AI services,” Microsoft wrote. “Our datacenters depend on the availability of permitted and buildable land, predictable energy, networking supplies, and servers, including graphics processing units (‘GPUs’) and other components.”

Microsoft’s nod to GPUs highlights how access to computing power serves as a critical bottleneck for AI. The issue directly affects companies that are building AI tools and products, and indirectly affects businesses and end-users who hope to apply the technology for their own purposes.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, testifying before the US Senate in May, suggested that the company’s chatbot tool was struggling to keep up with the number of requests users were throwing at it.

“We’re so short on GPUs, the less people that use the tool, the better,” Altman said. An OpenAI spokesperson later told CNN the company is committed to ensuring enough capacity for users.

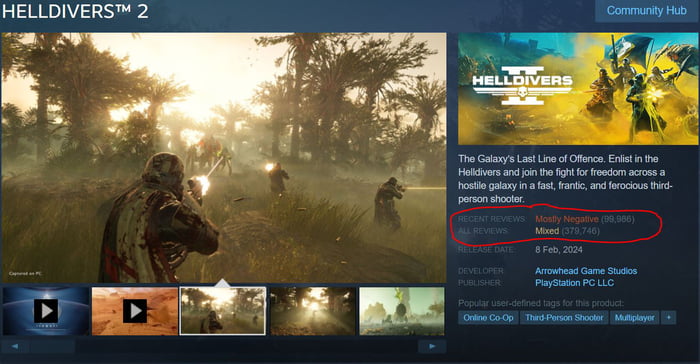

The problem may sound reminiscent of the pandemic-era shortages in popular consumer electronics that saw gaming enthusiasts paying substantially inflated prices for game consoles and PC graphics cards. At the time, manufacturing delays, a lack of labor, disruptions to global shipping and persistent competing demand from cryptocurrency miners contributed to the scarce supply of GPUs, spurring a cottage industry of deal-tracking tech to help ordinary consumers find what they needed.

But the current shortage is much different in kind, industry experts say. Instead of a disruption to supplies of consumer-focused GPUs, the ongoing shortage reflects the sudden, exploding demand for ultra high-end GPUs meant for advanced work such as the training and use of AI models.

Production of those GPUs is at capacity, but the rush of demand has overwhelmed what few sources of supply there are.

There is a “huge sucking sound” coming from businesses representing the unrivaled demand for AI, said Raj Joshi, a senior vice president at Moody’s Investors Service who tracks the chips industry.

“Nobody could’ve modeled how fast or how much this demand is going to increase,” Joshi said. “I don’t think the industry was ready for this kind of surge in demand.”

One company in particular stands to benefit massively from the AI surge: Nvidia, the trillion-dollar chipmaker that according to industry estimates controls 84% of the market for discrete GPUs. In a research note published in May, Joshi estimated that Nvidia would experience “unparalleled” revenue growth in the coming quarters, with revenue from its data center business outstripping that of rivals Intel and AMD combined.

In its May earnings call, Nvidia said it had “procured substantially higher supply for the second half of the year” to meet the rising demand for AI chips. The company declined to comment on Tuesday, citing its latest pre-earnings quiet period.

AMD, meanwhile, said Tuesday it expects to unveil its answer to Nvidia’s AI GPUs closer to the end of the year.

“There’s very strong customer interest across the board in our AI solutions,” said AMD CEO Lisa Su on the company’s earnings call. “There is a lot more to do, but I would say the progress that we’ve made has been significant.”

Compounding the issue is that GPU-makers themselves cannot get enough of a key input from their own suppliers, said Sid Sheth, founder and CEO of AI startup d-Matrix. The technology, known as a silicon interposer, works by marrying standalone computing chips with high-bandwidth memory chips and is necessary for completing GPUs.

The Biden administration has made increasing US chip manufacturing capacity a priority; the passage of the CHIPS Act last year is set to provide billions in funding for the domestic chip industry and for chip research and development. But those investments are aimed at a broad swath of chip technologies and not specifically targeted at boosting GPU production.

The chip shortage is expected to ease as more manufacturing comes online and as competitors to Nvidia also expand their offerings. But that could take as long as two to three years, some industry experts say.

In the meantime, the shortage could force companies to find creative ways around the problem. Companies that can’t get their hands on enough chips are now having to be more efficient, said Sheth.

“Necessity is the mother of invention, right?” Sheth said. “So now that people don’t have access to unlimited amounts of computing power, they are finding resourceful ways of using whatever they have in a much smarter way.”

That could include, for example, using smaller AI models that may be easier and less computationally intensive to train than a massive model, or developing new ways of doing computation that don’t rely as heavily on traditional CPUs and GPUs, Sheth said.

“Net-net, this is going to be a blessing in disguise,” he added.