Part one of a series about wrongful convictions in Detroit.

The day Mark Craighead lost his freedom for a murder he couldn’t have committed, he just wanted to come home and get some rest. He was tired and hungry.

But when he arrived at his home in Detroit on that warm, sunny evening in June 2000, two detectives were waiting on his porch and demanded he come downtown for questioning about his friend’s murder three years earlier.

Chole Pruett, 26, was found fatally shot inside his apartment in Detroit. His 1996 Chevy Tahoe was set ablaze behind an elementary school in Redford Township.

Craighead had to work at 5 a.m. the following day at a Chrysler plant. But the detectives, despite not having an arrest warrant, insisted he had no choice.

Craighead, who had no criminal record and coached youth football, had already been interviewed twice by Detroit police, and each time they were satisfied with his answers. But this time was different.

Waiting at police headquarters downtown was Detective Barbara Simon, an aggressive interrogator who spent years waging psychological warfare on young Black men accused of murder. In the 1990s and early 2000s, she engaged in investigative misconduct, illegally held suspects without a warrant, denied them access to an attorney or phone call, threatened them, and made false promises of leniency, judges and prosecutors would later determine. Suspects who refused to talk without an attorney were confined to jail cells infested with cockroaches, rats, and other vermin.

Her tactics led to false confessions and fabricated witness statements.

As Craighead rode in the rear of a squad car wearing shorts and a tank top, he had no idea what he was up against. He wasn’t allowed to call an attorney or make a phone call, according to affidavits and a subsequent lawsuit.

When they arrived at police headquarters at 1300 Beaubien, Craighead says he was confined for hours to a four-foot by four-foot locked room with a desk and steel grates on the window.

He was left alone with a growing migraine headache and nothing to eat or drink. When he pounded on the door and demanded to be let out, Simon told him to “sit down and shut up,” Craighead says.

Without a lawyer present, Craighead had no plans to answer questions.

But Simon, who was known as “the closer” for obtaining confessions, had another plan that worked with countless other suspects: Frighten him and wear him down.

When Craighead sat face to face with Simon, he repeatedly refused to answer questions. Simon claimed she had evidence linking him to the murder. Police took him to different rooms and left him alone for hours.

After 1 a.m., more than seven hours after he was taken into custody without a warrant, a lawyer, or a phone call, Simon told Craighead he would be released and still make it to work for his 5 a.m. shift if he agreed to take a polygraph. If he didn’t, he would remain in custody, Simon told him, according to court records.

Knowing the fallibility of polygraphs, Craighead took a risk and agreed. He just wanted to go home. Simon escorted him to another building, where he was strapped into a polygraph machine.

“She gave me no choice,” Craighead said, according to the affidavit. “I would lose my job.”

After about an hour of questions, Simon told Craighead he failed the polygraph, a conclusion that was later contradicted by another test. Falsely claiming the polygraph was admissible in court, Simon leaned in and said, “Your wife is going to find a new husband and your kids are going to call somebody else daddy if you don’t tell me what you did because you’re going to jail for the rest of your life without parole,” Craighead recalled in a deposition.

After he refused to confess to a murder that evidence would later show he didn’t commit, Simon placed Craighead in handcuffs and fingerprinted him. When asked if he could go home as promised, Craighead says Simon laughed at him.

After 4 a.m., Craighead was placed in a cold jail cell with no blanket or pillow. The only place to sit was a wooden bench with screws poking out. Mice and cockroaches scurried about, he says.

At least he had a chance to use a restroom for the first time since he arrived more than eight hours earlier.

“I was kind of scared and terrified,” Craighead recalled in a deposition.

At 11 a.m., a detective escorted Craighead back to the tiny interrogation room where he had sat for hours alone the night before. The officer rebuffed Craighead’s request for an attorney, phone call, and medicine for his migraine, he says.

Simon walked in and also denied his requests, according to Craighhead.

“We got you,” Craighead recalled Simon telling him. “We know that you shot Chole, and we can prove it.”

As Craighead would later find out, the police had no evidence linking him to the murder.

To Craighead’s surprise, Simon presented him with a detailed narrative about what went down on the night of Pruett’s murder in July 1997: He and Craighead got into a fight. Pruett pulled out a gun, and the pair struggled for control of it. The gun went off. Pruett died.

The alleged confession, which Simon handwrote, was contradicted by forensic evidence, which showed Pruett was shot four times in the back execution-style from a distance of at least two feet.

In her interview with Craighead, Simon insisted the shooting was an “accident” and said, “You don’t seem like the kind of person that would kill or rob your best friend, so you must have had a reason,” according to court records.

Simon handed him the “confession.” If he signed it, she promised the first-degree murder charges would be reduced, and he could go home, Craighhead recalled.

Broken down, scared, and disoriented, Craighead signed the paper — a decision that would cost him seven years in prison.

“I signed it to avoid going to prison for the rest of my life,” Craighead said during a deposition.

He had two children, ages 2 and 4.

Although Craighead and his attorney argued the confession was fabricated and coerced and that his rights were violated, a judge allowed prosecutors to use the written statement as the primary evidence against him, and he was convicted of manslaughter in 2002.

As the jury read the verdict, Craighead broke down in tears.

“I was crying,” he recalls. “I got hoodwinked. I hadn’t seen the light of day since they arrested me on my porch. It was traumatic.”

He wouldn’t be a free man until 2009, and it would take another 12 years until he was exonerated.

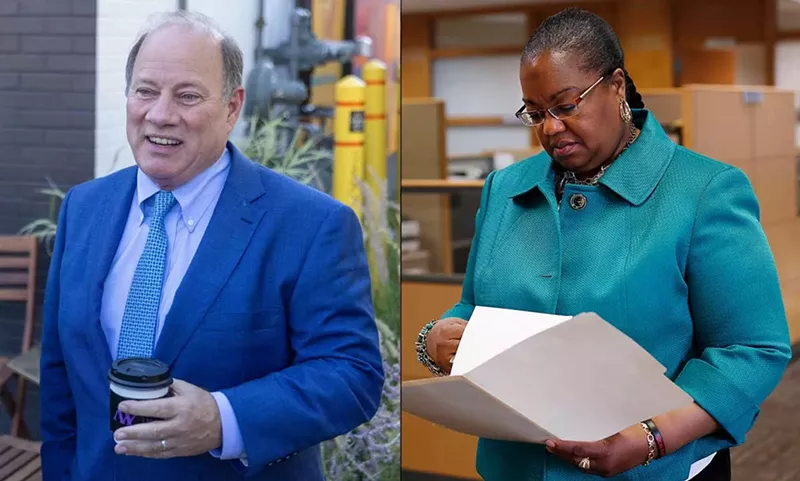

click to enlarge

Steve Neavling

Suspects and witnesses were rounded up and interrogated at the then-headquarters of the Detroit Police Department at 1300 Beaubien in downtown. The building was used by DPD until 2013.

Locked up and lied to

Craighead is among four Black men who have been exonerated of murder convictions after their attorneys showed that Simon, who is also Black, used deceptive and coercive interrogation techniques. A fifth Black man, who falsely confessed after being unlawfully imprisoned, was freed before his murder trial because DNA evidence showed he wasn’t the killer.

All five sued Simon and the city, and three of them have been settled so far at a cost to taxpayers of more than $16 million.

The two other lawsuits, including one by Craighead, are still wending their way through federal court and likely will cost the city millions more. Because the city is self-insured, Detroit must cover the costs of settlements and attorneys, diverting crucial resources away from essential public services.

Simon worked in the Homicide Division for about 20 years before she retired in 2010. Shortly after, then-Attorney General Mike Cox hired Simon as an investigator. She retired in August 2021.

A six-month Metro Times investigation, which included a review of thousands of pages of court documents and dozens of interviews with exonerees, inmates, defense attorneys, interrogation experts, private investigators, and law enforcement officials, paints a troubling picture of Simon and the prosecutors, police leaders, and judges who could have stopped her. Simon used aggressive, illegal, and sometimes violent interrogation techniques on suspects and witnesses, according to affidavits, court transcripts, and multiple lawsuits.

Here’s what we found, according to those documents:

• Suspects were routinely locked in small rooms for hours if they refused to talk and were denied access to attorneys and a phone call. In each of the cases, Simon had no arrest warrants to legally confine the suspects and witnesses.

• Simon falsely promised suspects, some of whom were teenagers, that they could go home if they signed confessions that she wrote.

• Simon illegally presented herself as a prosecutor who had authorization to file charges and falsely promised leniency if suspects signed statements admitting guilt.

• In one case, Simon called a suspect a racial slur and told him any jury in America would convict him of killing a white woman.

• While testifying at trial and during depositions, Simon often claimed she couldn’t recall basic information about the interrogations.

• She threatened to frame witnesses for murder or other crimes if they didn’t incriminate suspects who turned out to be innocent. Those witnesses later recanted.

Although the exonerations have shown that Simon resorted to psychological torment to elicit false confessions and fabricated witness statements, countless other suspects who were interrogated by the detective are still behind bars. During her career, Simon said she interrogated “hundreds” of suspects.

Metro Times tracked down eight other inmates who emphatically claim they were falsely convicted because of Simon’s interrogation tactics. Many of them were teenagers when they were convicted.

Attorneys and private investigators who have worked on the Simon cases believe many more innocent people are behind bars because of the detective’s interrogation tactics.

“There certainly are still innocent people in prison because of Simon,” David Moran, co-founder and a lead counsel at the Michigan Innocence Clinic, tells Metro Times. “There are likely a bunch.”

No accountability or justice

Despite what defense attorneys say was a clear and alarming pattern of Simon resorting to abusive, illegal, and deceptive tactics to get guilty verdicts, the exonerees and those still in prison have faced stiff resistance from judges and the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office. Time and time again, judges turned down appeals, and prosecutors fought to keep the men in prison, despite later admitting some of the defendants were innocent.

“The prosecutors will file an appeal, and they drag it through the appellate court for two to four years,” Steve Crane, a private investigator who helped get three innocent prisoners released, tells Metro Times. “They don’t want to accept a loss at any cost. It’s disgusting, and it’s frustrating.”

Those still in prison say they’re withering away behind bars because judges and prosecutors won’t consider their cases.

Their stories are strikingly similar to those who were exonerated. For up to eight hours, they were forced to undergo aggressive interrogations or were placed in a locked room without a warrant, food, or phone calls. They were falsely — and illegally — promised freedom if they confessed. And they were told there was undeniable evidence that would lead to their convictions, a claim they would later find out was untrue.

In each of the cases, Simon was one of the lead investigators. And she wasn’t just any detective. When Detroit police had trouble getting witnesses or suspects to talk, they often depended on Simon, who had an unusual — and many would say suspicious — record of obtaining confessions, albeit ones that had been repeatedly recanted or contradicted.

Defense attorneys have repeatedly said Simon had a history of ignoring or withholding evidence that suggested a suspect was innocent. She also falsely testified during murder trials. In one case, Simon testified that the defendant fatally stabbed the victim, which lined up with what turned out to be a coerced, false confession. The autopsy revealed the victim was beaten to death.

The stories behind the convictions are symptomatic of a dark, troubling, and often lawless time for Detroit’s homicide division. During a multiple-year investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice that began in December 2000, federal investigators found that homicide detectives trampled on the constitutional rights of suspects and witnesses for decades to get confessions. According to the DOJ, the department had a history of subjecting suspects and witnesses to false arrests, illegal detentions, and abusive interrogations. Despite what was at stake, the detectives weren’t properly trained, and bad cops were rarely disciplined, the DOJ concluded.

In 2003, to avoid a massive civil rights lawsuit claiming suspects and witnesses endured false arrests, unlawful detentions, fabricated confessions, excessive force, and unconstitutional conditions of confinement, the Detroit Police Department agreed to DOJ oversight in 2003. Because of the harsh interrogation tactics, DPD agreed in 2006 to videotape interrogations of all suspects in crimes that carry a maximum penalty of life in prison.

After 13 years of federal government scrutiny, the DOJ finally ended its oversight, but only after DPD agreed to sweeping changes in a consent decree to overhaul its arrest, interrogation, and detention policies. Detectives could no longer round up witnesses and force them to answer questions at police precincts and headquarters.

By then, the damage done during that time is impossible to measure. But what’s clear is that lives were destroyed, and many more innocent people are likely behind bars for crimes they didn’t commit, attorneys and private investigators say.

At no point since then have prosecutors or police tried to reexamine the cases during this troubling time.

“The Detroit Homicide Division was a trainwreck. It was completely out of control in the 1990s and early 2000s,” Moran says. “You have a police department that for a decade or more was rogue. There’s no other way to describe it. It’s undeniable.”

In 1997, three years before the DOJ’s investigation, the head of DPD’s Homicide Division, Joan Ghougoian, was accused of illegally obtaining murder confessions by falsely promising suspects they could go home. Monica Childs, a homicide detective at the time, blew the whistle on Ghougoian and was reassigned to another department. Childs alleged in a lawsuit against the department that Ghougoian attacked, cursed, bullied, and ignored her when she tried to prevent illegally obtained murder confessions from being used.

At the time, Simon was working in the Homicide Division.

Although she is by no means the only Detroit homicide detective to be accused of eliciting false confessions and witness statements during that time, the volume of allegations and the resulting exonerations make Simon stand out in a department plagued by accusations of misconduct.

Despite the attention the whistleblower lawsuit and DOJ investigation brought to the police department, Simon continued to illegally obtain confessions, according to lawsuits, affidavits, and depositions.

‘A stupid [n-word]’

On Mother’s Day in 1999, Lisa Kindred was getting inside her family van with her three children when a lone gunman rushed up and shot her in the chest on Bewick Street on the city’s east side. To save her children, the 35-year-old Roseville woman drove away and pulled into a gas station to ask for help. She fell out of the car and was later pronounced dead at a hospital. Her children huddled in the back seat, screaming and crying.

The children, ages 1o days to 8 years old, were uninjured.

Within hours, police rounded up two alleged witnesses, both of whom were heavily intoxicated on drugs and alcohol, according to a lawsuit that was later filed. One was a 16-year-old who was illiterate and dropped out of high school. The other had mental health issues and heard voices.

Both interrogations “turned to physical abuse,” and Simon and another cop choked one of the alleged witnesses, according to court records. One of the interrogations lasted six hours, and Simon allegedly threatened to frame two suspects or they’d be implicated in the murder, according to court records. She wrote up the statements and told them to sign the papers.

Afraid they’d be charged, the pair signed the statements, leading to the arrests of Justly Johnson, 24, and Kendrick Scott, 20, on the day of the shooting.

During an interrogation, Simon called Johnson a racial slur and told him any jury in America would convict him of killing a white woman, according to Johnson. Simon added that she was under pressure from then-Mayor Dennis Archer to close the case and didn’t care if he was innocent, according to one of Johnson’s affidavits.

He said Simon didn’t investigate his alibis and she responded that “it didn’t matter because the mayor was her boss and her boss was on them and they were going to charge me with the murder whether I was innocent or not.”

Johnson, who had a baby on the way, said he “begged” Simon “not to do this to me.”

“Ms. Simon then asked me how far I had gone in school,” Johnson recalled. “I told her I had gone through 1oth grade. She then called me a ‘stupid [n-word]’ and repeated that I needed to confess to this crime that I did not do.”

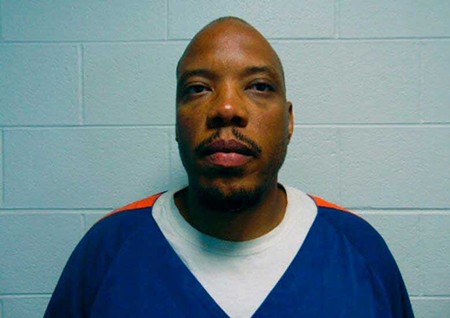

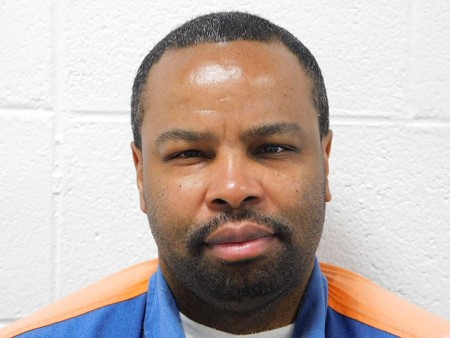

click to enlarge

Michigan Department of Corrections

Kendrick Scott.

Simon repeated the slur and that a jury was going to convict a Black man of killing a white woman, even if he didn’t commit the crime.

“At that point I broke down in tears, begged investigator Simon for my life and continued to protest my innocence,” Johnson said. “Investigator Simon then stormed out of the room.”

In January 2000, Johnson was convicted of murder, assault with intent to commit robbery, and felony use of a firearm. He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Scott was convicted of the same charges in May 2000 and was also sentenced to life without parole.

Johnson and Scott never gave up on getting out of prison and proving their innocence.

In 2009, Scott Lewis, an investigative reporter in Detroit, began reviewing the case. Two years later, he sent a letter to the victim’s son, Charmous Skinner Jr., who at the time of the shooting was 8 years old. He was in the front seat when his mother was shot and said he’d never forget the shooter’s face. He described the gunman as being in his mid-30s with a heavy beard and very large nose, neither of which matched the description of Johnson or Scott. He also said the shooter was alone.

Lewis contacted the Michigan Innocence Clinic, which had recently taken on the case. Law students and a supervising attorney from the clinic interviewed Skinner and showed him photographs of Johnson and Scott. Neither of them was the gunman, he said. Skinner said he was “a hundred percent” positive.

Even though Skinner had seen the killer, police never interviewed him.

Despite the new evidence, the clinic couldn’t get a judge to look at the case.

Wayne County Circuit Judge Prentis Edwards denied a motion for relief from judgment in 2011, without even holding a hearing. In 2013, Wayne County Circuit Judge James Callahan also denied the motion without a hearing, and the Michigan Court of Appeals declined to grant the defense permission to appeal.

Finally, in 2014, the Michigan Supreme Court ordered the cases to be remanded to circuit court for a joint hearing to determine whether Scott and Johnson were entitled to a new trial.

During the hearing, one of the alleged witnesses said he had falsely implicated Johnson and Scott and that police “whooped” him during the interrogation. A cousin of the other alleged witness, who died in 2008, said her cousin admitted to her that he lied to investigators because he was afraid of being charged.

“At that point I broke down in tears, begged investigator Simon for my life and continued to protest my innocence,” Johnson said. “Investigator Simon then stormed out of the room.”

Defense attorneys also provided reports that showed the victim’s husband, Will Kindred, had been involved in “a series of violent domestic incidents” with his wife. At one point, he even threatened to kill her whole family, according to the records. On at least two occasions, police confiscated .22-caliber weapons from the husband after two of the alleged domestic violence incidents.

The weapon used in the murder was a .22-caliber gun.

Nevertheless, the judge denied a motion for a new trial in August 2015, concluding that Kindred was likely murdered as part of a planned contract killing that involved Scott and Johnson.

After the Michigan Court of Appeals upheld the ruling, the Michigan Supreme Court finally ordered new trials for Johnson and Scott in July 2018.

On Nov. 28, 2018, the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office dismissed the charges, and Scott and Johnson were free men for the first time in 18 years.

Johnson and Scott filed separate lawsuits in U.S. District Court against Simon and another Detroit cop, Catherine Adams, claiming they coerced two witnesses into falsely implicating them in the murder and engaged in “deliberate and knowing fabrication of evidence.”

In November 2022, the city of Detroit settled the lawsuits, agreeing to pay Johnson and Scott $8 million each.

Johnson’s attorney, Wolfgang Mueller, says lawsuits and media exposure are the most effective ways to prevent police departments and prosecutors from putting innocent people in prison.

“Publicity and lawsuits help improve the system,” Mueller tells Metro Times. “You have to hit people in the pocketbook. It’s when they get hit in the pocketbook that they make changes. When this stuff comes out of the dark, then change can be made. We as a society won’t tolerate it if we know about it. It’s just that for so long people didn’t know about it.”

Coercive tactics

In February 2000, Nathan Peterson found himself face to face with Simon, accused of fatally shooting a man. Moments earlier, he says, he was riding in the rear of a police car with a cameraman.

Like the others, Peterson, who was 23 at the time, says he was isolated in a room for hours before Simon began threatening him.

“During the interrogation, she was using this cameraman as a tool to try to threaten to expose me to the media as a murderer,” he tells Metro Times. “She says if I didn’t agree to what she said, she was going to embarrass me and portray me as a murderer. … I was thinking of my family. I didn’t want my mom to get embarrassed.”

Simon claimed she had plenty of evidence against him to get a jury to convict him, threatened to take away his son, and promised to set him free if he confessed, he says.

“She presented herself as a prosecutor,” Peterson says. “She said she was willing to help me if I helped myself. She said if I agree to sign a statement, I could go home and face lesser charges. She had already convinced me that she had already arrested me and charged me with murder.”

During an interrogation, police are barred from making promises about charges since those decisions fall under the prosecutor’s authority.

“I was ready to get out of there, and I was willing to do anything,” he recalls.

Peterson says Simon wrote the statement and told him to sign it. According to the statement, Peterson wrestled the victim with a gun and shot him in the back twice.

Peterson was charged with murder and immediately incarcerated.

His first trial ended in a hung jury in July 2001.

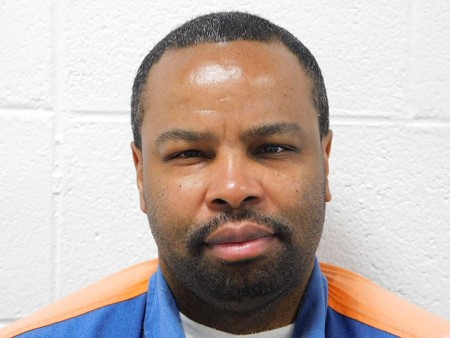

click to enlarge

Michigan Department of Corrections

Nathan Peterson.

Peterson says police and prosecutors changed the narrative of the shooting during the second trial, and he was convicted.

“My thing with Simon, she knew I didn’t do what she said I did,” Peterson says.

At a hearing before the trial, Simon initially denied there was a cameraman but changed her story when Peterson’s attorney said they had a witness. They tried to get a copy of the video footage but never got it.

Under oath, Simon insisted she didn’t use any form of persuasion to get Peterson to sign the confession. Simon also insisted she couldn’t recall any details of the interrogation, a claim she repeatedly made under oath in other cases.

Peterson says he doesn’t believe Simon thought he was guilty.

“Their only concern was just closing the case,” he says. “That’s all she was concerned about. They weren’t concerned whether I was innocent or not. They virtually kidnapped me off the street and did what they wanted with me.”

Peterson remains in prison and has been unable to convince courts or prosecutors to review his case.

The Reid technique

James L. Trainum, a former longtime homicide detective in Washington, D.C., and an expert and consultant on interrogations and confessions, says Simon’s tactics were psychologically coercive and could easily lead to false confessions.

He says Simon uses a controversial method of interrogation known to create false confessions. Called the “Reid technique,” the method is aimed at increasing suspects’ anxiety by creating a high-pressure environment, such as confining them to a room for hours and saying they are going to spend the rest of their lives in prison. The interrogator then presents evidence — real or invented — to suggest that police already have proof of the suspects’ guilt. The technique was developed by former Chicago cop and polygraph expert John E. Reid in the 1950s.

To elicit a confession, the interrogator provides explanations that frame the suspect’s actions as justifiable or excusable, even though the interrogator knows the statement will lead to charges. A prime example is getting suspects to say they killed someone by accident.

The idea is to make the suspect believe that confessing is the easiest way out.

The problem is, experts say, the technique is inherently manipulative and can foster confirmation bias in investigators and overwhelm suspects to such a degree that they believe lying is better than telling the truth.

Years of research and numerous exonerations have demonstrated that the Reid technique can easily result in false confessions.

“The suspects are presented with a situation where they feel like they are going to get screwed,” Trainum tells Metro Times. “They are being guaranteed that they are going to be convicted by an authority figure. Then they start talking about leniency and say the judge will like it much better if they confess. They’ll say, ‘If you take responsibility, they are going to go much lighter on you.’ It’s a forced choice.”

Trainum adds, “What the interrogation process is doing is limiting your options. They are able to lie to you about the evidence. All of that puts you in a vice.”

The method has been banned in several European countries. In Canada, Provincial Court Judge Mike Dinkel ruled in 2012 that “stripped of its bare essentials, the Reid technique is a guilt-presumptive, confrontational, psychologically manipulative procedure whose purpose is to extract a confession.”

One of the largest police consulting firms in the U.S., Wicklander-Zulawski & Associates, announced in 2017 that it stopped training detectives in the Reid technique, which it had taught since 1984. The technique was being misused and prompting false confessions, the firm said.

“Confrontation is not an effective way of getting truthful information,” Wicklander-Zulawski & Associates President and CEO Shane Sturman said at the time. “Rather than primarily seeking a confession, it’s an important goal for investigators to find the truth ethically through a respectful, non-confrontational approach.”

In 2021, Illinois and Oregon barred police from lying to minors. The U.S. House is considering a bill that would render statements made during interrogations inadmissible if a court determines the officer deliberately used deceptive tactics, such as fabricating evidence or making unauthorized promises of leniency.

To reduce false confessions, Trainum says the U.S. needs to abolish the Reid technique.

Of the more than 3,550 exonerations nationwide, about 13% involved false confessions, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. The most famous case is known as the Central Park Five. It involved five Black and Latino teenagers wrongfully convicted of raping a jogger in New York City’s Central Park in 1989, only to be exonerated in 2002 after another individual confessed and DNA evidence confirmed his guilt.

More than half of those exonerated are Black. In fact, innocent Black people are seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than innocent white people, a reflection of the persistent biases in the criminal justice system, according to a 2022 report from the registry.

To juries, confessions are highly incriminating and they alone can lead to convictions, Trainum and other experts say.

“A false confession trumps all other evidence, and it still does in a lot of cases because people say, ‘I wouldn’t have confessed, so I don’t see why they would have,’” Trainum says. “Even today when it comes to exonerations, you can have DNA evidence and people will still fight it and say they confessed.”

Trainum believes false confessions are more common than statistics suggest because they “are the hardest cases to get exonerated.”

Another problem, he says, is that police departments in the U.S. don’t tend to invest enough in training detectives to interrogate suspects, leaving the accused in unqualified hands.

In a deposition in Craighead’s lawsuit in January 2023, Simon said she went to “several classes” to learn how to take witness statements and remembered “maybe once going to an outside seminar” on interrogations. She admitted she never received training by the Michigan State Police or the FBI, two agencies that typically provide courses on interrogations.

She also said she couldn’t remember ever talking with prosecutors about the constitutional rights of suspects.

Nevertheless, she estimated she conducted “hundreds” of interrogations during her roughly 20 years in the Homicide Division.

Lawsuits filed against Simon also pointed out that she failed to ensure the confessions were factual. Had she bothered to verify the statements from the exonerees and others, some of the confessions would have been thrown out and could have prevented innocent people from going to prison, according to the lawsuits.

The confessions also omitted basic information that would verify whether the suspect was truthful about committing a crime. While questioning Craighead, for example, Simon didn’t bother to ask basic questions, like what kind of gun he used, when he arrived at the murder scene, and which part of the victim’s body he shot.

Since it turned out that Craighead wasn’t the shooter, he wouldn’t have been able to answer the questions truthfully.

When asked by Craighead’s attorney Mueller whether she “thought it’d be important” to ask him about the type of gun he used, Simon called the question “stupid.”

Undeterred, Mueller asked, “Does it sound reasonable to you, that a detective investigating a homicide, and there’s a gun, would want to know what kind of gun?”

“Yes. Yes,” Simon responded.

Michigan has safeguards in place that are intended to protect defendants who were coerced into giving false confessions. In what is called a “Walker hearing,” judges are responsible for determining the voluntariness and admissibility of a defendant’s confession before the trial. It is a crucial safeguard meant to ensure that any confession used in court was made without coercion, undue influence, or violation of the defendant’s rights.

However, judges have been reluctant to throw out confessions, even when there is compelling evidence that the confessions were not voluntary. That’s because judges are quick to side with prosecutors and police, even when detectives like Simon have demonstrated a pattern of eliciting false confessions and violating defendants’ constitutional rights, legal experts and defense attorneys say.

‘It’s akin to slavery’

In 1996, a year before Craighead’s friend was murdered, Lamarr Monson was accused of fatally stabbing a runaway 12-year-old girl at a drug house on Detroit’s west side. Like Craighead, Monson had no criminal record, was interrogated for hours by Simon, and was denied access to a phone and a lawyer, according to court records.

Monson, who was 24 at the time, was convicted of murder and sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison based on a false confession that was later contradicted by evidence that should have been presented at his trial.

Monson had a 6-year-old daughter at the time. She would be an adult by the time he was exonerated.

“When you are innocent of a crime and put in prison, it’s the same emotional feeling of being kidnapped and taken from your family,” Monson tells Metro Times. “It’s akin to slavery.”

After more than 20 years behind bars, Monson was finally exonerated in August 2017, in large part because Wayne County prosecutors believed the “confession” was coerced. Simon was also accused of providing prosecutors with false information about crucial physical evidence and withholding inculpatory evidence.

At the trial, Simon testified that the girl, Christina Brown, died from multiple stab wounds, a claim that fit the narrative in the false confession but contradicted the autopsy that found the victim died of blunt force trauma to the skull and brain. Simon later said her false testimony was an “honest mistake.”

“For her to sit there and create false narratives to convict someone of a crime, you have to be a wicked person,” Monson says. “She was destroying lives. She was sabotaging justice and has willingly done this regularly.”

Monson still vividly recalls the afternoon of Jan. 20, 1996, the day he walked into an abandoned apartment where he had sold drugs and found Brown sprawled out on the bathroom floor, lying in a pool of blood and gasping for breath. Her head was swollen.

“She raised her hands and tried to say my name,” Monson recalls. “I told her I was going to get help. I was banging on doors, trying to call 911. I went to my sister’s house [two blocks away] and told the operator there was a girl in need of medical attention.”

Monson says he sprinted back to the bathroom, covered Brown in a blanket, and propped her up so she wouldn’t choke on her blood. He also began chest compressions.

Brown was later pronounced dead at a nearby hospital.

Two other people at the apartment did nothing to help, Monson says.

Police ordered Monson and the two others to get into a squad car, where they were taken to police headquarters.

Simon denied Monson his right to use a phone or contact an attorney and questioned him for more than four hours, according to court records. Simon told him he could call his parents if he signed a statement that claimed he had sex with Brown, an allegation he vehemently denies and says Simon fabricated to “dirty me up” and “make me look like a monster.”

Monson was forced to spend the night in jail and barely slept. The next morning, without having anything to eat, he was promised he could call his parents and go home if he signed a confession, according to his lawsuit.

Like in Craighead’s case, Monson was told he would spend the rest of his life in prison unless he signed a statement that claimed the killing was accidental and that he got into a physical confrontation with the victim. According to the alleged confession, Monson accidentally stabbed Brown in the neck with a knife she had been holding.

Never mind that Brown actually died of blunt force trauma, presumably from being beaten with the top of a toilet tank.

Police either failed to get fingerprints from the knife and the toilet lid or they never disclosed the findings. If they had, they would have discovered that the fingerprints didn’t belong to Monson and in fact belonged to Robert “Raymond” Lewis, who was also at the house and questioned by police.

In 2012, Lewis’s ex-girlfriend told police that Lewis bought drugs from Brown on the morning she was killed and that he returned “covered in blood.” He said he “had to kill that bitch” because she had scratched him, according to his ex-girlfriend.

Police didn’t focus on Lewis at the time because he had incriminated Monson.

It would take another five years after that statement for Monson to be exonerated, in no small part because the prosecutor’s office continued to insist he was guilty.

While he was in jail, Monson’s family spent $10,000 on an attorney who brought him no closer to getting him free. Without any money left, Monson taught himself how to file his own motions and appeals. He wanted to get fingerprints from the weapons used in the murder, but each court rebuffed him.

Nearly 15 years after he was sentenced to prison, Monson had all but given up. He felt demoralized and helpless.

“God blessed this circumstance,” Monson says. “I took my hands off this and said, ‘I did all I can.’”

Finally, in about 2011, the Michigan Innocence Clinic agreed to take Monson’s case and began the arduous task of fighting to get the weapons fingerprinted. At each step, the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office defended the handling of the case and argued Monson was guilty.

Then in September 2016, a state court ordered police to analyze the top of the toilet tank, a basic step that should have been taken 19 years earlier. The results were eye-opening: Two of the fingerprints belonged to Lewis, and none of them matched Monson’s. The knife later went missing, making it impossible to analyze during the appeals process.

It was also discovered that police failed to analyze fingerprint and blood samples from the victim’s clothing, the knife, and male clothing on the floor.

With the new evidence and an affidavit from Lewis’s girlfriend, a court finally granted Monson’s motion for a new trial on Jan. 30, 2017.

Rather than trying to convince a jury that Monson was guilty in the face of the new evidence, the prosecutor’s office dismissed the case on Aug. 25, 2017, and Monson was exonerated and finally became a free man.

In a statement at the time, the prosecutor’s office indicated that Monson’s confession may have been coerced.

“Due to the destruction of evidence, issues surrounding the way the police obtained Monson’s confession and the passage of time, we are unable to re-try this case,” Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy said. “For similar reasons we are not able to charge anyone else in connection with the murder of Christina.”

Worthy also admonished the police department for failing to keep evidence that could exonerate an innocent person.

“The failure of the DPD to retain critical evidence potentially threatens the very foundation of the criminal justice system and the faith placed in it by the people we protect,” Worthy said, adding that she and others met with then-DPD Chief James Craig to raise the issue of the destruction of evidence in capital cases. The meeting resulted in Craig agreeing to a joint workgroup to develop an evidence retention policy.

Despite evidence that Lewis may be the real killer, he was never charged. Two investigators for the prosecutor’s office traveled to Pittsburgh to interview him, and he admitted he lived in the same apartment as the victim and bought drugs from her. But, according to the prosecutor’s office, he was “in poor physical health and denied any involvement in the death of Christina Brown.”

In February 2018, Monson filed a lawsuit against the city and Simon, along with several other officers. The case is still in court and headed for a trial in October.

“Now the chickens are coming home to roost,” Monson says.

All these years later, Monson is still in disbelief.

“I still can’t believe this happened,” Monson says. “They will willingly frame an innocent person and will not accept any responsibility for doing so. It’s a slap in the face.”

Monson says it stings even more that a Black woman played a major role in his wrongful imprisonment.

“For a Black woman to not understand your plight as a Black man, and for her to be in a position to make things fair for you, she picked the side that abuses you and takes advantage of you, instead of seeking out the truth,” Monson says. “It’s incomprehensible that a Black woman would go to that extent to lock a young Black man in prison.”

In a written statement, DPD declined to comment on Simon’s tactics but said it “expects every member to follow the rules and regulations of the Department.”

Since the 1990s and early 2000s, DPD said it “has implemented measures including video recording of interrogations, audits and inspections to ensure members are acting in accordance with policy and that there is supervisory review.”

A spokesman added, “We have high standards for every member of our Department, especially those who have sworn to protect, serve and respect the constitutional rights of all.”

This story continues next week in part two.