There is room for a continued selloff in U.S. Treasurys which has already pushed 10- and 30-year yields to their highest levels since 2007 and 2011, according to researchers at Barclays.Though the recent selloff took a breather on Friday, the steady drive higher in long-dated yields which unfolded this week left observers warning that the era of low rates may be firmly behind the U.S. as a new normal appears to take shape in the bond market. Long-term rates yields are just beginning to enter ranges that have been historically consistent with where they traded during the early 2000s.Read: Why Treasury yields keep rising,…

Tag: U.S. 1 Year Treasury Bill

-

‘Eye-popping’ borrowing need from U.S. Treasury raises risk of buyers’ fatigue

Just a day after the Treasury Department released a $1 trillion borrowing estimate for the third quarter, questions are being raised about the extent to which foreign and domestic buyers can continue to keep up their demand for U.S. government debt.

Further details about Treasury’s financing need will be released at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday. For now, the $1 trillion estimate, the largest ever for the July-September period, has analysts concluding that the U.S. is facing a deteriorating fiscal deficit outlook and continuing pressure to borrow.

At stake for the broader fixed-income market is whether the presence of large ongoing auctions over the coming quarter and beyond will lead to a prolonged period where demand from potential buyers might begin to dry up, Treasury yields edge higher, and the government-debt market returns to some form of illiquidity.

“You can make the argument that since 2020, with the onset of Covid, that Treasury issuances have been met with reasonably good demand,” said Thomas Simons, an economist at Jefferies

JEF,

-1.75% .

“But as we go forward and further away from that period of time, it’s hard to see where that same flow of dollars can come from. We may be looking at recent history and drawing too much of a conclusion that this borrowing need will be easily met.”Simons said in a phone interview Tuesday that “the risk is that you don’t get continued demand from foreign or domestic buyers of fixed income.” The result could be “six to nine months where the market is fatigued by bigger auction sizes, Treasurys become more and more difficult to trade, there’s a grind higher in yields, and there may be issues with liquidity where markets may not be so deep.” Still, he expects such a period, if there is one, to be less acute than what was seen in the 2013 taper tantrum or last year’s volatility in the U.K. bond market.

On Monday, the Treasury revealed a $1.007 trillion third-quarter borrowing estimate that was $274 billion higher than what it had expected in May. The estimate — which Simons calls “eye-popping” — assumes an end-of-September cash balance of $650 billion, and has gone up partly because of projections for lower receipts and higher outlays, according to Treasury officials.

Monday’s estimate is the largest ever for the third quarter, though not relative to other parts of the year. In May 2020, a few months after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S., Treasury gave an almost $3 trillion borrowing estimate for the April-June quarter of that year.

For the upcoming fourth quarter, Treasury is now expecting to borrow $852 billion in privately-held net marketable debt, assuming an end-of-December cash balance of $750 billion. According to strategist Jay Barry and others at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

JPM,

-1.05% ,

the third- and fourth-quarter estimates “suggest that, at face value, Treasury continues to expect a wider budget deficit” for the 2023 fiscal year.As of Tuesday, investors appeared to be less focused on the Treasury’s borrowing needs than on signs of continued strength in the U.S. labor market, which raises the prospect of higher-for-longer interest rates. One-

TMUBMUSD01Y,

5.400%

through 30-year Treasury yields

TMUBMUSD30Y,

4.100%

were all higher as data showed demand for workers is still strong. Meanwhile, all three major U.S. stock indexes

DJIA,

+0.05% COMP,

-0.41%

were mostly lower in morning trading.According to Simons, who the most likely buyers will be at Treasury’s upcoming auctions will depend on where the department decides to focus its issuances. If the focus is on bills, then money-market mutual funds could “move some cash over,” he said. And if it’s on long-duration coupons, it would be “real money” players such as insurers, pension funds, hedge funds and bond funds — though much will rely on inflows from clients “before demand would pick up.”

-

A debt-ceiling deal will spark a new worry: Who will buy the deluge of Treasury bills?

When the U.S. debt-ceiling fight finally is resolved, the Treasury is expected to unleash a flood of bill issuance to help refill its coffers run low by the protracted standoff in Washington, D.C., over the government’s borrowing limit.

Treasury bills are debt issued by the U.S. government that mature in four to 52 weeks. New bill issuance could reach about $1.4 trillion through the end of 2023, with roughly $1 trillion flooding the market before the end of August, according to an estimate from BofA Global strategists.

They expect the deluge through August to be about five times the supply of an average three-month stretch in years before the pandemic.

“The good news is that we have a high degree of confidence around who is going to buy it,” said Mark Cabana, rates strategist at BofA Global, in a phone interview with MarketWatch. “The bad news is that it’s not going to be at current levels. Things have to cheapen.”

Cabana sees a key buyer of bill supply unleashed by a debt-ceiling deal in money-market funds, which have climbed to nearly $5.4 trillion in assets managed since the regional banking crisis erupted in March (see chart).

So people who yanked billions of dollars in deposits from banks after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March and parked them in money-market funds could end up playing an encore performance in this year’s debt-ceiling drama.

Money-market funds swell since March, topping $5 trillion in assets

BofA Global

Related: Money-market funds swell to record $5.4 trillion as savers pull money from bank deposits

$2 trillion at Fed repo facility

Money-market funds have been the main reason why at least $2 trillion consistently sits overnight at the Federal Reserve’s reverse repo facility. The program was last offering a roughly 5% rate, a level Cabana said new Treasury bills might need to exceed by about 10-20 basis points.

“It’s an unintended consequence of a debt-ceiling deal getting done,” said George Catrambone, head of fixed income Americas at DWS Group, about market expectations for heavy short-term Treasury bill issuance, but he also expects money-market funds, foreign buyers and other institutions auctions to continue as buyers in the market.

“There’s always buyers. It’s a question of price.”

President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif. met Monday to talk about potential ways to raise the $31.4 trillion borrowing limit and to avoid a “doomsday” scenario in financial markets if the U.S. defaults. As talks resumed Wednesday, McCarthy said, “I think we can make progress today.”

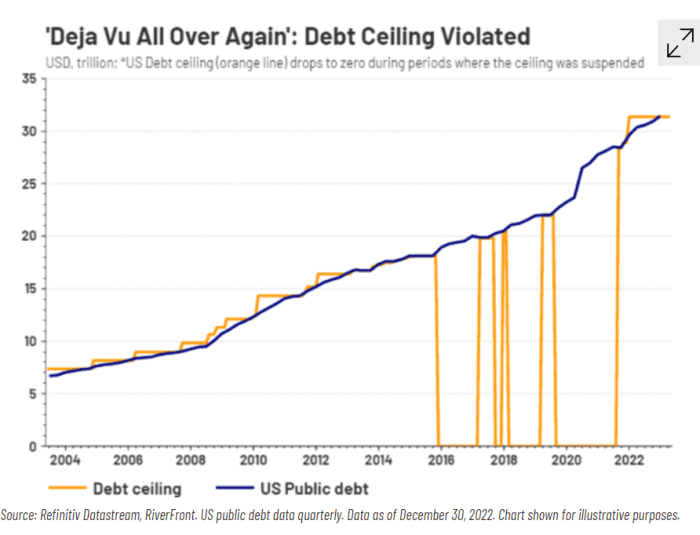

Congress has struck deals each time U.S. public debt has exceeded its debt ceiling in the past, including by suspending it eight times since 2016 (see chart).

In the past when the U.S. debt-limit has been violated, Congress extended or suspended it

Refinitive, RiverFront

That doesn’t mean financial markets have been sitting by idly. The 1-month Treasury yield

TMUBMUSD01M,

5.616%

rose to 5.6% on Wednesday, while the 3-month yield

TMUBMUSD03M,

5.350%

was 5.3%, according to FactSet. Bill maturing around the “X-date,” which could come as soon as June 1, have even higher yields.Read: Debt-ceiling angst sends Treasury bill yields toward 6%

“Those are obviously pretty heady yields,” Catrambone said. “But it also exemplifies the market having to price in potential market disruptions in the month of June,” even though his team, like many in financial markets, expect that eventually “cooler heads will prevail” in Washington as the debt-ceiling standoff heads down to the wire.

Stocks were lower Wednesday, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

-0.75%

off almost 300 points, or 0.9%, on pace for a fourth day in a row of losses, according to FactSet. The S&P 500 index

SPX,

-0.83%

was off 0.9% and the Nasdaq Composite Index was down 0.9%.How the money ran out

The Treasury in January hit its borrowing limit and began operating under “extraordinary measures” to avoid a default.

Cash balances at the Treasury Department have since dwindled to less than $100 billion, according to economists at Jefferies. Barclays strategists estimate its cash balance may fall below $50 billion between June 5-15.

“Basically, we are just draining our cash account to fund operations while we wait to figure out the debt ceiling,” said Lindsay Rosner, senior portfolio manager at PGIM Fixed Income.

But when the battle over the debt limit ends in a resolution, she expects longer-dated Treasury yields to increase, as haven buying on fears of potentially a full U.S. government default and a credit rating downgrade will have been taken off the table.

“The Armageddon, whatever small probability people were pricing in of catastrophe, remove that,” she said. “And that means the worst economic outcome has been removed.”

That’s also a reason why Rosner has been avoiding ultrashort Treasurys in the eye of the debt-ceiling fight in favor of 2, 3 or 4-year bonds offering some of the highest yields in years.

“We’re being afforded good yield, good spread, a couple of years out the curve,” she said. “Play that game.”

Read next: How will the Fed react to the debt ceiling breach? Here are some plays in the playbook.

-

‘Getting on an elevator with no buttons’: How the 2-year Treasury became the financial instrument to watch in March and a Wall Street obsession

It was a two-week trading period like few had ever seen in the $24 trillion Treasury market.

In a span of roughly nine trading sessions between March 7 and 17, the yield on 2-year Treasury notes — a gauge of where U.S. central bankers are most likely to take interest rates over the next two years — sank a full percentage point to 3.85% from an almost 16-year closing high above 5%, with wide swings in both directions on the way down.

The 2-year yield’s yearlong upward trajectory made a sudden and dramatic descent, as investors swung from a view that interest rates would remain higher for longer to a scenario in which the Federal Reserve might need to cut borrowing costs to avert a deep recession and repeated bank failures. The wild swing in sentiment turned the 2-year Treasury rate

TMUBMUSD02Y,

4.178%

into a roller-coaster ride and made it the most exciting space to watch in the traditionally staid government-debt market.For traders like David Petrosinelli of InspereX in New York, a 25-year veteran of markets, March’s daily volatility was akin to “getting on an elevator with no buttons,” he said. He recalls telling people at his firm, who were worried about the positions they held at the time, that “a lot of this is a knee-jerk reaction to the unknown” — even if it felt both “eerily reminiscent” of rates volatility seen ahead of the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and “distinctly different’’ because it was driven by rapidly changing market expectations for the Fed and contained within the U.S. regional-banking system.

Read: What ‘unprecedented’ volatility in the $24 trillion Treasury market looks like

For more than a decade, there wasn’t much to say about the 2-year Treasury yield because the U.S. was mired in mostly low interest rates and “no one knew how to trade it,” according to Petrosinelli, 54, who began his career in the late 1990s as a as a portfolio manager focused on asset-backed and residential mortgage-backed securities. It was an overlooked rate in a sleepy corner of the market and nobody paid it much attention. That changed beginning in 2022, when monetary policy makers finally undertook the most aggressive rate-hike campaign in four decades to combat inflation — reinforcing the 2-year yield’s role as the best proxy for where the market thinks interest rates will end up. The 2-year yield rocketed to above 5% in early March from 0.15% in April 2021.

Suddenly, the 2-year Treasury became the most watched financial indicator on Wall Street, influencing the trajectories of stocks and the U.S. dollar throughout much of 2022. “This thing is relentless,” declared market commentator Jim Cramer on CNBC last year. He told viewers he was buying 2-year notes, not meme stocks. “The run to 4 is probably the most punishing one I can recall for the 2-year.” Other prominent names like Mohamed El-Erian, the former chief executive of PIMCO, and Jeffrey Gundlach, founder of DoubleLine Capital, wanted to talk about it. “If you want to know what’s going to happen in the year, follow the 2-year yield at this point,” El-Erian said on CNBC. “That’s the market indicator that has the most information.” More hedge funds and macro private-equity firms jumped on board and started trading it, said InspereX’s Petrosinelli. And head trader John Farawell of Roosevelt & Cross in New York, said family and friends who never showed much interest in fixed income before began regularly asking him if it was the right time to buy the 2-year Treasury note.

“Once we started to hit 4% on the 2-year yield last September for the first time since 2007, everyone got interested,” said Farawell, 66, a trader for the past 41 years. He estimates that interest in the 2-year yield among his firm’s clients has gone up about 30% in the past 12 months. “We have seen retail customers suddenly saying they want to put their money to work in the 2-year note because of an interest rate that we have not seen in years.”

From his office in Midtown Manhattan, Nicholas Colas noticed an abrupt and unexpected shift over the past year and it had to do with the 2-year Treasury. As the co-founder of DataTrek Research, a Wall Street research firm, Colas realized that the 2-year Treasury yield was influencing trading in the stock market. When the 2-year Treasury yield shot higher in 2022, the equity market would become volatile and often drop. In fact, the 2-year Treasury seemed to influence equity-market volatility in both directions. Whenever the 2-year yield briefly stabilized, Colas said, stocks tended to rally since equity investors took the stabilization in the 2-year rate to mean that Fed policy was “no longer as much of a wild card.”

To Colas, equity markets appeared to be taking any selloff in the 2-year note, and thus a rise in its corresponding yield, as a sign that the Fed would have to increase interest rates by more than expected and keep them higher for longer. With stocks and U.S. government debt both getting trounced regularly in last year’s selloffs, Colas said his first thought was that “all of a sudden, Treasurys were no longer a safe haven — something that has rarely happened since I started my career in 1983.”

Trading in government debt, like elsewhere in financial markets, is a two-way street of buyers and sellers. When yields are moving higher, that means the price of the corresponding Treasury security is dropping — and vice versa. The 2-year Treasury note pays out a fixed interest rate every six months until it matures. The trick to trading it, as opposed to buying and holding, is to either sell it before its underlying value gets destroyed by higher interest rates, or to buy it before the Fed starts cutting rates — which would, theoretically, produce a lower yield and make the government note more expensive.

Throughout the yield’s march higher, investors sold off the underlying 2-year note — a move which diminished the note’s value for existing holders like banks, pension funds, credit unions, foreign central banks, and U.S. corporations. Two-year Treasury notes also constitute about 1% to 2% of the total holdings at the 10 largest actively managed money-market funds, according to Ben Emons, senior portfolio manager and head of fixed income at NewEdge Wealth in New York.

“Policy expectations are what really drive the 2-year yield,” said Thomas Simons, a U.S. economist at Jefferies, one of the two dozen primary dealers that serve as trading counterparties of the Fed’s New York branch and help to implement monetary policy. “We had a major paradigm shift in terms of what investors’ expectations were for the sustainability of higher inflation and what the Fed would do in response. The impact on markets has been far less appetite for risk than there otherwise would be,” with stocks putting in a dismal performance in 2022, though generating somewhat better 2023 returns.

Tucked into the note’s selloff, though, was plenty of interest from prospective government-debt buyers, which helped temper the magnitude of the 2-year yield’s rise once the rate got to 4%. Many looking to buy were individual investors hoping to benefit from higher yields and to diversify away from stocks, said traders like Tom di Galoma, a managing director for financial services firm BTIG.Historically, banks, mutual funds, hedge funds, foreign investors and even the Fed have been the biggest buyers of Treasurys across the board; some of those players, particularly foreign central banks and money-market mutual funds, are mandated to buy and hold government debt. All two dozen primary dealers are involved as market makers for the 2-year security, stepping in to buy it in the absence of either direct or indirect buyers.

The 2-year note remains a reliable source of funding for the U.S. government, given the consistent demand for the maturity, which enables the U.S. Treasury Department to “raise a lot of cash quickly, if needed,” said Simons of Jefferies. In 2020, for example, when the government authorized $2.4 trillion in Covid-related spending and relief programs, the amount of 2-year notes sold at auction was one of the biggest of any maturity — far exceeding the 10- and 30-year counterparts — “because it had the capacity to handle that.’’

Sources: Treasury Department, Bureau of Public Debt, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Currently, the Treasury has $1.421 trillion in total outstanding 2-year notes, representing about 13% of all the debt issued out to 10 years, according to Treasurydirect.gov. The most recent 2-year note auction in March was for $42 billion — more than the 10-year note sale.

Fallout from the banking sector and worries about a potential recession altered the trajectory of the 2-year starting in March, triggering concerns that the Fed’s rate-hike cycle had gone too far. Fresh buyers poured into the 2-year space and pushed the yield below 4% — driven by the view that rates weren’t likely to go much higher from here and that policy makers might cut them by year-end.

Substantial downside volatility in the 2-year Treasury yield has actually helped to stabilize stock prices this year, in Colas’ estimation, because it’s been interpreted as the bond market’s sign that the Fed is approaching the end of its rate-hiking cycle. Like InspereX’s Petrosinelli, Colas says he had visions of the 2007-2008 financial crisis during March’s flight-to-quality trade, which occurred amid regional bank failures and “significantly more stress than the market was expecting.”

As of Thursday morning, the 2-year rate was at 4.17%, below the Fed’s benchmark interest-rate target range — implying that traders still believe policy makers will follow through with rate cuts. That’s a turnabout from the thinking that prevailed over most of 2022 through early last month, when the 2-year rate had been on an aggressive march toward 5% as the Fed continued to hike rates to combat inflation.

Meanwhile, poor liquidity continues to plague the Treasury market broadly, based on Bloomberg’s U.S. Government Securities Liquidity Index, which measures prevailing conditions. According to the New York Fed, the Treasury market was relatively illiquid throughout last year — making it more difficult to trade. As a result, there was a widening in the bid-ask spread — or difference between the highest price a buyer is willing to pay versus the lowest price a seller is willing to accept — of the 2-year note relative to its average.

“The volatility we’re seeing in the 2-year, we think, is largely a function of uncertain Fed rate hiking expectations coupled with poor liquidity,” said Lawrence Gillum, the Charlotte, N.C.-based chief fixed income strategist at LPL Financial.

“The 2-year is the most sensitive to changing policy expectations and since this Fed is ‘data dependent,’ any and all new data that could potentially change the inflation/economic growth narrative has increased volatility substantially,” Gillum said in an email. “As the Fed’s rate hiking campaign comes to an end (we think there is one more hike and then they’ll be done), we would expect the volatility to decline. Moreover, the Treasury and Fed are looking at ways to improve liquidity, but so far nothing has happened. Hopefully, they will do something, though, since the Treasury market is arguably the most important market in the world.”

At InspereX, Petrosinelli regards the 2-year note as an “anchor” to any short-term portfolio, and says that “it’s not a bad place for investors to hide out for at least a year.’’ That’s because even if the yield does come down, “investors wouldn’t be getting too hurt price-wise,” he said. “We think the Fed will leave rates elevated for some time.”

However, the 2-year could continue to dip below the fed-funds rate on soft economic data, especially related to consumption, later this year, Petrosinelli said. In order for the 2-year rate to go above the Fed’s main interest-rate target — now between 4.75% and 5% — “people would have to think the Fed is behind the curve again on inflation.”

For Farawell of Roosevelt & Cross, which was founded in 1946 and is one of Wall Street’s oldest independently owned municipal-bond underwriters, the 2-year note “has become such an attractive asset class for us’’ that “you almost can’t go wrong with putting money in it.” Friends and family “ask me about this 2-year and say, ‘It sounds good.’ I say, ‘It’s a great rate, you should buy it — until the Fed starts to change course.’”