The spice cumin can work as well as orlistat, the “anal leakage” obesity drug.

In my video Friday Favorites: Benefits of Black Cumin for Weight Loss, I discussed how a total of 17 randomized controlled trials showed that the simple spice could reduce cholesterol and triglyceride levels. And its side effects? A weight-loss effect.

Saffron is another spice found to be effective for treating a major cause of suffering—depression, in this study, with a side effect of decreased appetite. Indeed, when put to the test in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, saffron was found to lead to significant weight loss, five pounds more than placebo, and an extra inch off the waist in eight weeks. The dose of saffron used in the study was the equivalent of drinking a cup of tea made from a large pinch of saffron threads.

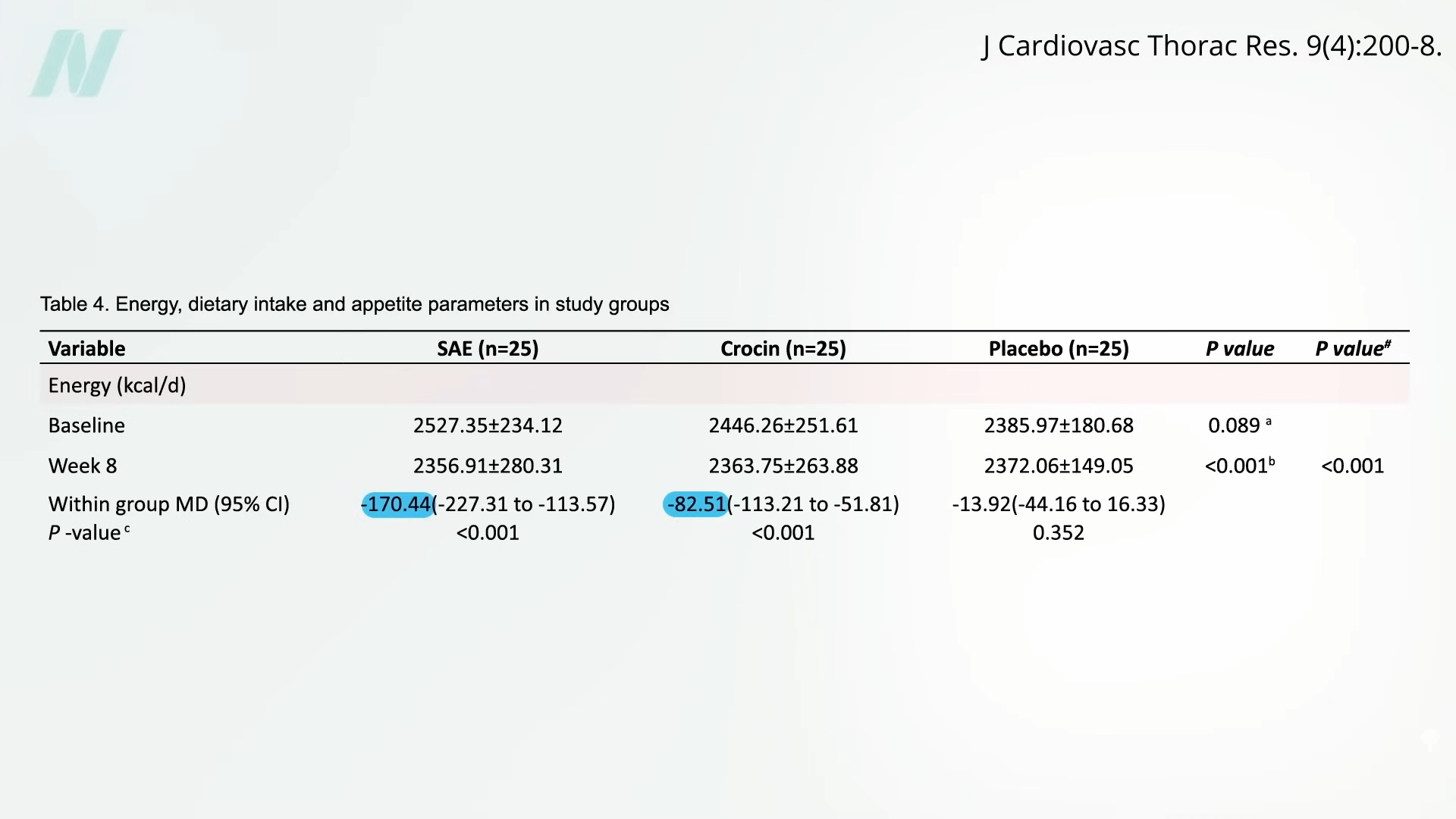

Suspecting the active ingredient might be crocin, the pigment in saffron that accounts for its crimson color, as shown here and at 0:59 in my video Friday Favorites: Benefits of Cumin and Saffron for Weight Loss, researchers also tried giving people just the purified pigment.

That also led to weight loss, but it didn’t do as well as the full saffron extract and only beat the placebo by two pounds and half an inch off the waist. The mechanism appeared to be appetite suppression, as the crocin group ended up averaging about 80 fewer calories a day, whereas the full saffron group consumed an average of 170 fewer daily calories, as you can see below and at 1:21 in my video.

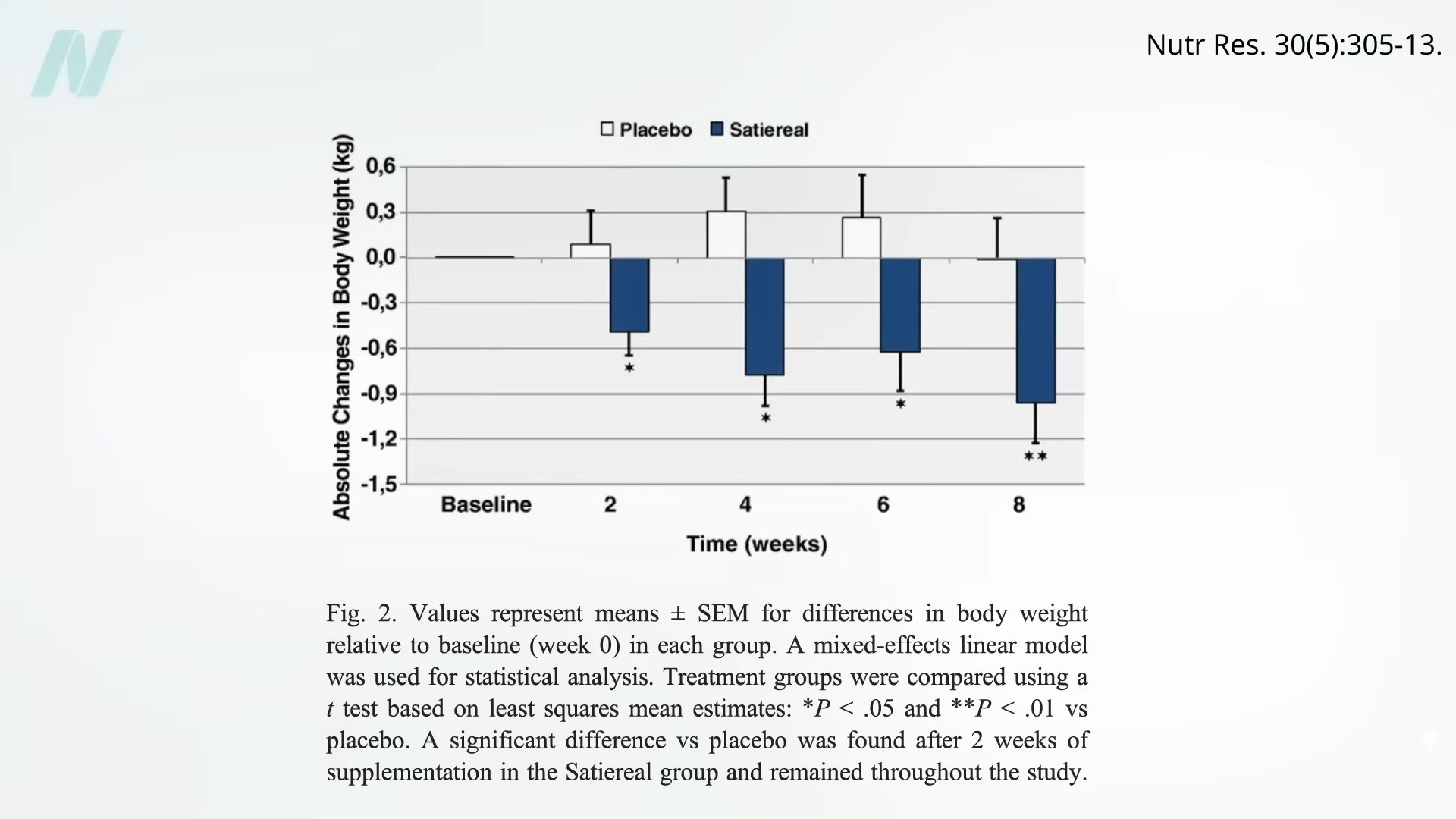

A similar study looked specifically at snacking frequency. The researchers thought that the mood-boosting effects of saffron might cut down on stress-related eating. Indeed, eight weeks of a saffron extract halved snack intake, compared to a placebo. There was also a slight but statistically significant weight loss of about two pounds, as you can see here and at 1:41 in my video, which is pretty remarkable, given that tiny doses were utilized—about 100 milligrams, which is equivalent to about an eighth of a teaspoon of the spice.

The problem is that saffron is the most expensive spice in the world. It’s composed of delicate threads sticking out of the saffron crocus flower. Each flower produces only a few threads, so about 50,000 flowers are needed to make a single pound of spice. That’s enough flowers to cover a football field. So, that pinch of saffron could cost a dollar a day.

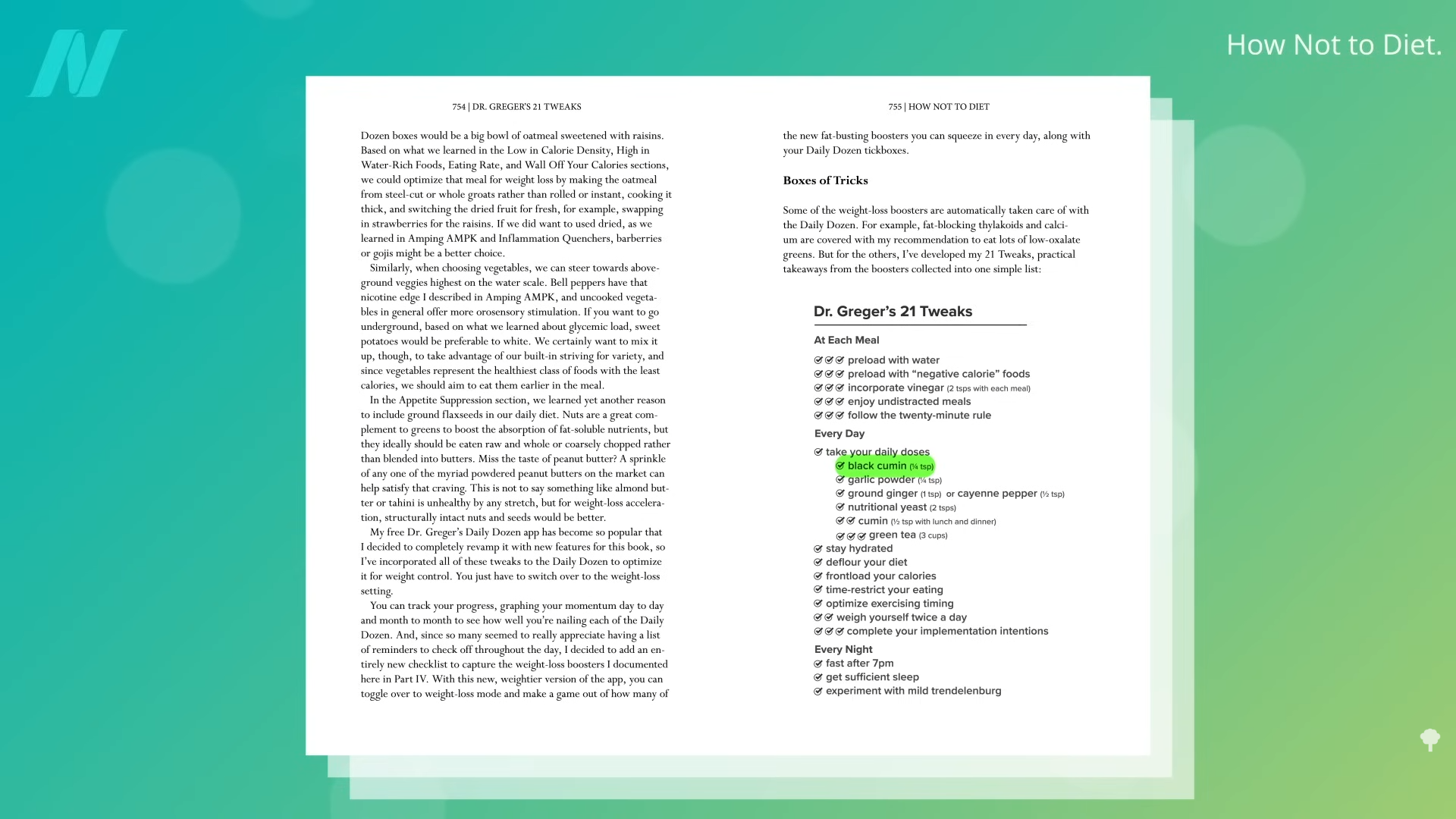

That’s why, in my 21 Tweaks to accelerate weight loss in How Not to Diet, I include black cumin, instead of saffron, as you can see here and at 2:30 in my video. And, at a quarter teaspoon a day, the daily dose of black cumin would only cost three cents.

What about just regular cumin? Used in cuisines around the world from Tex-Mex to South Asian, cumin is the second most popular spice on Earth after black pepper. It is one of the oldest cultivated plants with a range of purported medicinal uses, but only recently has it been put to the test for weight loss. Those randomized to a half teaspoon at both lunch and dinner over three months lost about four more pounds and an extra inch off their waist. The spice was found to be comparable to the obesity drug known as orlistat.

If you remember, orlistat is the “anal leakage” drug sold under the brand names Alli and Xenical. The drug company apparently prefers the term “faecal spotting” to describe the rectal discharge it causes, though. The drug company’s website offered some helpful tips, including: “It’s probably a smart idea to wear dark pants, and bring a change of clothes with you to work.” You know, just in case their drug causes you to poop in your pants at the office.

I think I’ll stick with the cumin, thank you very much.

Doctor’s Note

The video on black cumin that I mentioned is Friday Favorites: Benefits of Black Cumin Seed (Nigella Sativa) for Weight Loss.

My other videos on saffron are in the related posts below.

For an in-depth dive into weight loss, see my book How Not to Diet.

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

Source link