November 19, 2025

What Is Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Learning Theory?

by TeachThought Staff

What did Vygotsky say about learning?

Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory describes learning as a fundamentally social process and locates the origins of human intelligence within cultural activity. A central theme of this framework is that social interaction plays a primary role in cognitive development: knowledge is first constructed between people and later internalized by the individual (Vygotsky, 1978).

Also known as the Sociohistorical Theory, Vygotsky’s model emphasizes how cultural context, shared activities, and especially language shape the development of higher mental functions. Learning and development are inseparable from the social and cultural environments in which individuals participate.

Vygotsky argued that learning unfolds on two levels—initially through interaction with others and then within the learner’s internal psychological processes. As he explained: “Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological)… All the higher functions originate as actual relationships between individuals” (Vygotsky, 1978).

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

| Concept | Brief Explanation | Classroom Example |

|---|---|---|

| Zone of Proximal Development | The space between what a learner can do alone and what they can do with guidance. | A student solves multi-step math problems only after the teacher models the first step. |

| Social Interaction | Learning develops through guided interaction with more knowledgeable others. | Peers discuss a science concept and clarify it for each other using everyday language. |

| Cultural Tools & Mediation | Language, symbols, and cultural practices shape thinking and problem-solving. | A teacher models how to read a graph, and the student later uses the same conventions independently. |

| Scaffolding | Temporary instructional support that fades as the learner gains mastery. | Students begin with sentence starters but later write independently as supports fade. |

| Private Speech | Self-directed speech that becomes internalized and guides problem-solving. | A child whispers instructions to themselves while assembling a puzzle. |

Let’s take a look at the principles of his learning theory.

Key Concepts of Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory

1. Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

According to Vygotsky, the Zone of Proximal Development “is the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem-solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers.” This idea aligns with broader perspectives on cognition described in “Learning Theories for Teachers.”

Through collaborative interactions, a more skilled person, such as a teacher or a peer, can provide support to scaffold the learner’s understanding and skills. This emphasis on guided learning is similar to principles discussed in Principles of Social Learning Theory.

This ‘zone’ is a level of understanding or ability to use a skill where the learner is able, from a knowledge or skill standpoint, to grasp or apply the idea but only with the support of a More Knowledgeable Other (Briner, 1999).

Example: A student can solve multi-step math problems only when the teacher models the first step; over time, the student internalizes the process and completes similar problems independently. Another example is a reader who can summarize a text when guided with prompts (“What happened first?”) but not alone.

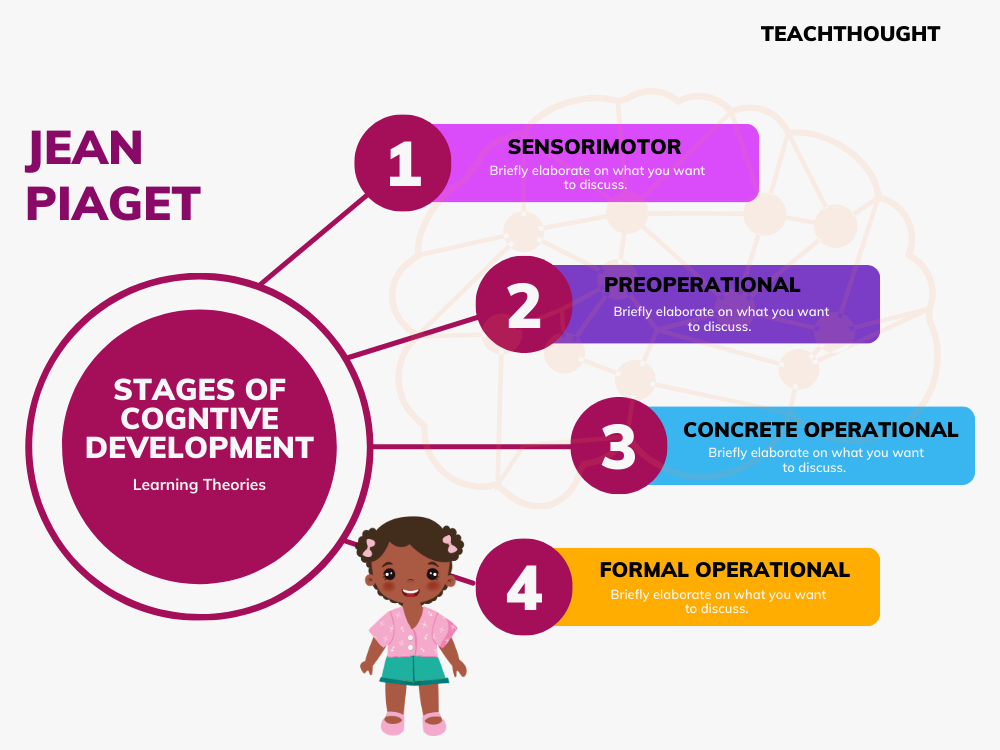

This ‘MKO’ can be another student, parent, teacher, etc.—anyone with a level of understanding or skill that allows the student to master a knowledge or skill that could not otherwise be mastered. Strategies that support work in this Zone of Proximal Development include modeling, direct instruction, collaborative learning (closely related to the distinctions discussed in The Difference Between Constructivism and Constructionism, the Concept Attainment Model, Combination Learning, and more.

2. Social Interaction

Vygotsky emphasized the importance of social interactions in cognitive development. He believed that learning occurs through interactions with others, particularly more knowledgeable individuals. Language plays a central role in these interactions, as it enables communication, the transmission of knowledge, and the development of higher mental processes. These ideas connect to the learner-centered approach described in Constructionism (See above).

Example: A student learning a new science concept becomes more proficient after discussing it with a peer who explains it in everyday language. Similarly, a teacher-led think-aloud during a reading activity models how to analyze a text, helping students internalize the reasoning process.

Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory said that “Learning occurs through vicarious reinforcement–observing a behavior and its consequences (which have social ramifications).” Vygotsky shares this idea.

3. Cultural Tools and Mediation

Vygotsky argued that cultural tools, including language, symbols, artifacts, and social practices, mediate learning and development. These tools are products of a particular culture and are used by individuals to think, communicate, and solve problems. Through cultural tools, individuals internalize and construct knowledge, transforming their cognitive processes. This broader perspective is elaborated in Learning Theories for Teachers.

Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first on the social level, and later on the individual level (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 57).

Example: A student initially learns how to interpret a graph by watching a teacher model how to read axes and identify patterns; later, the student uses those same conventions independently. Another example is a child using teacher-provided sentence frames (“I predict that…”) before eventually generating their own academic language.

4. Scaffolding

Scaffolding is any help, assistance, or support provided by a more competent individual (e.g., a teacher) to facilitate a learner’s understanding and skill development. The scaffolding occurs by gradually adjusting the level of support according to the learner’s needs, and transferring responsibility to the learner as their competence increases. These ideas align with principles of adult learning described in Andragogy

Example: A teacher initially solves a writing prompt alongside students, then provides sentence starters, and eventually removes supports as students gain confidence. Another example is using guided questions (“What might you try next?”) during problem-solving before stepping back to let the learner take full control.

Scaffolding, and similar ideas like The Gradual Release of Responsibility Model: Show Me, Help Me, Let Me, also support the kinds of thinking described in Levels of Integration for Critical Thinking.

5. Private Speech and Self-Regulation

In his research (see also Types of Questions) Vygotsky noticed that young children often engage in private speech, talking to themselves as they carry out activities.

He believed private speech is important in self-regulation and cognitive development—a truth clear to parents and teachers but significant here as a data point observed by a neutral researcher. Over time, this private speech becomes internalized and transforms into inner speech, which is used for self-guidance and problem-solving.

Example: A child assembling a puzzle might whisper, “This piece goes here… no, try the corner,” using speech to guide their actions before eventually solving puzzles silently. Another example is a student verbalizing the steps of a math problem (“First multiply… then add…”) before learning to manage those steps internally.

References

-

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978).

Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. -

Bandura, A. (1977).

Social learning theory.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. -

Knowles, M. S. (1980).

The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy.

New York, NY: Cambridge Books.

TeachThought Staff

Source link