Peter Frick-Wright: It might be satire, I guess. But it doesn’t read like satire. It might be a stunt, I guess, designed to start a trend by pretending there is already a trend, but if that’s it, they really didn’t think it through.

It is an ad for Heinz Ketchup. And in this ad, the company, Heinz, writes that “runners everywhere are fueling their runs with ketchup.”

That’s the first text that shows up on the screen. Which, OK, maybe?

Ketchup is chock full of sugar, that’s good. Ketchup is also free at most restaurants, which might appeal to the dirtbag runner types out there. And it comes in a packet, just like energy gels, so, easy to carry with you, also good. But, that’s pretty much where the idea falls apart.

Here’s how we know runners everywhere are not fueling their runs with ketchup.

For starters, to get the recommended number of calories per hour, you’d need to consume something like 30 ketchup packets. One, every other minute. You’d barely have time to run.

And if you were to eat 30 ketchup packets, that is way too much sodium. It would be an absolute gut bomb. You’d be chugging water just to keep from throwing up.

In fact, there are a lot of reasons why runners are not fueling their runs with ketchup. The New York Times did a whole story on how this trend really isn’t a trend. Friends don’t let friends eat ketchup while running.

But producer Maren Larsen wanted to know: If not ketchup, what should runners eat? And does any of it sound appetizing to her girlfriend?

Kareena Tulloch: My name is Kareena Tulloch, and I am Maren Larsen’s girlfriend.

Maren Larsen: My girlfriend. You’re my girlfriend.

Kareena: Yeah. The Maren Larsen.

Maren: This is my partner Kareena. She’s a strong athlete with one pretty big weakness.

Kareena: I’ll just be out on a lovely trail run or a bike ride and be like, ‘wow, this is so pretty, this is so pretty, like, I don’t want to stop.’

I can go farther, I can go farther, and then I’ve gone too far.

Maren: Let me tell you about one such day when she headed out too far. That was the case one beautiful day this fall when she headed out on her bike for a training ride.

Kareena: I was like, oh yeah, this sounds like a really good bike ride. My friend recommended it. And so, I think it was supposed to be around 40 miles, maybe. I did plan to bring snacks and I completely forgot to bring snacks.

Maren: Didn’t you, like, have them all laid out or something?

Kareena: Yeah, I think I, like, had them on my kitchen counter and I just completely forgot.

Maren: Right, right. And how much water did you bring?

Kareena: I brought one. Water bottle?

Maren: Like, describe, like, what kind of water bottle?

Kareena: You know the, you know, like, the water bottles that fit on your bike?.

Maren: Yeah. So. The smallest possible.

Kareena: Yeah. Yeah. Yep.

Maren: Got it.

Kareena: So, and I think I was gonna put a, like, electrolyte packet in there, and I just completely forgot. It was just water.

Maren: You were just, like, too excited to go on your bike ride to worry about surviving it.

Kareena: Yeah, yeah. Exactly. I was just like, oh my gosh, this sounds super fun. And so I started the bike ride.

Maren:Kareena headed off on her 40-mile ride, and soon found herself playing leapfrog with another cyclist. She got just a tiny bit competitive, and before she knew it, she was on a longer route than she’d planned.

Kareena: So I think it was around 50 miles that I ended up biking that day. Basically the whole bike ride back, I was like, food, food, food, food, food, food, food. I just couldn’t stop thinking about food.

Maren: Kareena made it home that day, but barely. She had to stop at a 7-Eleven just a few blocks from her apartment. There, she gulped down a gatorade and loaded up her bike jersey with snacks to devour the moment she got home.

How did you feel after your little 7-Eleven feast?

Kareena: Decadent.

Maren: Decadent?

Kareena: Yeah.

Maren: Tired?

Kareena: Yeah, I was so tired, I think I just like laid there, I laid on my couch the rest of the day.

Maren: It’s likely that 7-eleven run narrowly saved Kareena from bonking. Bonking is a bit of endurance sports lingo that refers to what happens when your muscles completely run out of glycogen, which is what we call glucose stored in your muscles. Bonking means you’ve used up all your glycogen, and it messes you up. Both physically and mentally. It can be dangerous. And it’s unfortunately a phenomenon Kareena is all too familiar with.

Kareena: I love being active. I just don’t know how to fuel.

Maren: To address this problem, Kareena has tried everything over the years: everything, that is, from eating and drinking very little while exercising to forgetting to fuel entirely. Not water, not food, not gels or gummies or anything with electrolytes in it. She avoids it all, despite the super sick running hydration vest her girlfriend got her, which has two soft flasks and plenty of room for snacks.

Just saying.

As she branched out to the other endurance sports and her efforts grew longer, her strategy remained the same.

Until that day on her bike.

That near-bonk at mile 50 was a wakeup call for Kareena, because that ride was actually part of her training for her first ever triathlon: a half iron man, this summer. And a 50-mile bike ride is just under a third of what she has ahead of her: 1.2 miles of swimming, 13.1 miles of running, and 56 miles on the bike.

I’m really excited for you. I’m also a little nervous for you. And I think when we were talking about this, like the other day, a couple days ago, I made an analogy that I thought was really funny, which is that you are like a fancy new sports car, but you’re putting like absolute garbage in the tank, and sometimes just forgetting to put anything in the tank.

So you’re like in the middle of a drag race that you could totally win and then you run out of gas.

I’ve been there to see what happens when Kareena runs out of gas. One day when we were on a trip and I was working from our hotel room, she decided to occupy herself with a six-mile trail run, a very average workout for her. But she didn’t eat breakfast or lunch, and neither of us can remember her drinking much water. By the time she returned to the hotel room in the early afternoon, she was in rough shape.

Kareena: I remember walking up the stairs to the hotel room and I was like, like, I had to stop halfway because I was getting dizzy.

Made it back into the hotel room and just like laid down, and you like, I can’t, you made me quesadilla, I think.

Maren: Yeah, in the hotel microwave.

Kareena: Yeah. With like cheese and yeah.

Maren: Didn’t you like throw up in a trash can?

Kareena: Oh yeah, I did. And I remember I like couldn’t stand. Like, I tried to stand up and I got like super dizzy so I just had to like sit on the couch. It’s not good. Like, I’m not proud of it.

I’m not happy to be talking to you about like my failures, uh, and I know I need to get better at it. I just don’t really know how.

Maren: Well, good thing your girlfriend is a podcast producer. Which means I am going to find the answer for you, because I’m worried about you dropping dead in the middle of a race.

As my partner’s number one cheerleader, I consider it part of my job to keep her from keeling over during her triathlon. To help me accomplish that, I called up some experts.

Abby Chan: Nutrition is important. Especially once you get into big endurance things like anything beyond, I would even say half marathon, marathon.

Maren: This is Abby Chan.

Abby: It is essential, and it is the number one thing that goes wrong.

Maren: And this is Alyssa Moukheiber.

Alyssa: A lot of us don’t have the education around like how to eat or fuel ourselves in just like a really realistic manner and we really tend to struggle.

Maren: Both Abby and Alyssa are registered dieticians who work with athletes. You might remember them from the time they helped me demystify the suspiciously common experience of having a post-adventure craving for a cheeseburger. I asked them to come back to see if they could help Kareena. And they reassured me that she’s not alone.

Abby: As a dietician, granted I work in this field, people come to me for help. So this is going to be a little biased, but I have yet to meet an athlete that I’m like, yeah, you’re doing a great job. You’re totally, you’re good. You’re dialed.

Maren: For a variety of reasons, both physiological and financial, people tend to take up endurance sports as adults. Many played other sports as kids or ran shorter distances in high school or college. And maybe because of their previous experiences, beginner endurance athletes tend to think they know how to take care of themselves in competition. But they often don’t.

Alyssa: I was talking to one of my athletes the other day and I was telling them, I’m like, one of the major beefs I have with how like specifically teenagers are getting into sports is that we’re teaching them skills.

But we were never taught like the same emphasis of how to rehab for those skills, how to prep for those skills or how to fuel for those skills.

Maren: As a result, lots of talented endurance athletes bonk in their first big race and don’t know why. Or they know why, but don’t know what to do about it. It’s so common it’s almost become a rite of passage.

Next time there’s a marathon in your town, go to mile 20 and watch strong athletes that have been running 8-minute miles stop and walk. Three hours is about as long as the average person can muscle through that kind of effort without refueling.

There’s so much most of us don’t know about nutrition. Take for example the humble calorie, the biggest number in that black Nutrition Facts box. It’s so familiar. But what actually is a calorie, anyway?

Alyssa: Anytime I’m talking about calories with my clients, I talk about it in the term of like, what is it? It’s a unit of energy. Like an inch is a unit of measurement. A calorie is a unit of energy.

Maren: There are a lot of different forms that energy can take, but they’re all measured using the same unit. So if you’ve ever seen a quote-unquote energy drink with “zero calories,” that’s just marketing. There’s no actual energy in that drink. Just stimulants.

The calorie is to the human body as the gallon of gasoline is to the internal combustion engine. Calories are what make you go.

But not all calories are the same. There are fat calories, protein calories, and calories from carbohydrates, among others. Not all of those are good mid-effort endurance fuel. And giving yourself the right kind of calories, when you need them, can mean the difference between sprinting to the finish line and sprinting to the porta potties.

So the first thing to understand about feeding yourself during competition and training is that getting calories while you’re exercising is, in fact, not “just eating.” It’s fueling. And yes, there is a difference.

Alyssa: I Use the term mechanical eating a lot or practical eating. Yeah, I’m not that hungry, but it would be really helpful if I ate right now, like very strategic. I think sometimes that’s where fueling can come in.

Maren: For our purposes, the difference between eating and fueling is a matter of context. Eating is what you do in daily life when you’re hungry. Fueling is what you do during training or a race to avoid bonking where if you’re hungry, it’s already too late.

And because of the way your body absorbs calories, much of the time, mid-effort fueling for endurance sports is actually the opposite of what’s considered balanced nutrition the rest of the time.

Most of the time, you want calories to absorb slowly, so your body can use the energy it’s getting as it’s getting it between meals. You want a balance of nutrients, including carbohydrates, fat, and protein, plus fiber, vitamins, and minerals.

During endurance sports, on the other hand, your body is burning energy so fast that you want calories that can be absorbed quickly. And fat, protein, and especially fiber all put the brakes on digestion, slowing it down so that the nutrients don’t all hit the bloodstream at the same time.

Essentially, you want your energy absorption pace to match the pace you’re moving. When you’re moving slowly, you want to absorb energy slowly. When you’re trying to tackle your first-ever triathlon? Not so much. You want a lot of energy, right away. And that means carbohydrates, also known as sugars.

But just like there are different kinds of calories that absorb at different speeds, there are different kinds of sugars too. You’ve likely heard of the big three before: glucose, fructose, and sucrose.

Abby: All carbohydrates eventually lead to glucose. That’s basically what happens. So carbohydrates are sugar. Sugar are carbohydrates. That’s what it is. And so there’s many different types, and that’s also going to depend on how well you absorb it or digest it.

Maren: Glucose is the simplest sugar, and it is absorbed directly into your bloodstream without additional processing. Fructose has to first be processed by your liver before it can be absorbed, making it a slower release sugar. And sucrose, the scientific name for table sugar, consists of molecules that are half fructose and half glucose, and have to be broken down by enzymes in your digestive tract before being processed, making them the slowest sugar.

Abby: That’s really important because our system does max out on how much glucose it can absorb in a certain amount of time. So we can actually absorb more if it’s glucose and fructose,

Maren: The key to fueling for endurance is giving your body the types of fuels it can absorb quickly. But mixing those fuels with things like protein, fat, and fiber slows down the absorption process in a multitude of different ways. And remember, that’s a good thing if you’re sitting at a desk all day. You want to absorb energy slowly. But if you’re out biking or running all day, you want food that’s as easy to digest as possible. If it’s not, well, there are consequences.

Abby: When we’re training and exercising, our body is stressed out. Which is fine. It’s not inherently bad, but what’s going to happen is our body will start to shunt blood flow to our muscles, which therefore means our gastrointestinal tract is going to have less blood flow as well. And we need blood flow in order to digest our food. So if we don’t have blood flow and we’re just all of a sudden loading it with a heavy amount, it’s going to end up sitting in there. It can lead to more like diarrhea, nausea, all those things that aren’t super fun.

Maren: Okay, so you’re looking for calories that you can access quickly and won’t upset your stomach, which means you want glucose, fructose, and sucrose. And in general, for efforts longer than an hour, you want to avoid fat and fiber to make sure that your body can absorb those sugars as quickly as possible.

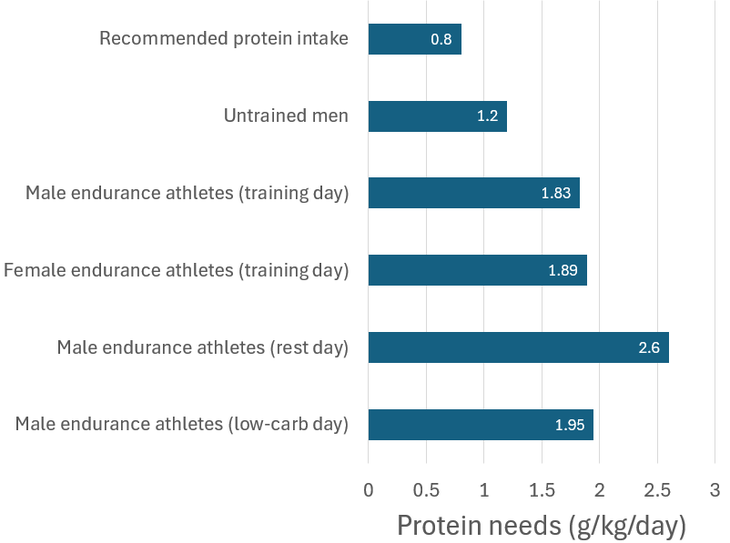

How much fuel do you want, though? Abby says it depends, and gives the caveat that most of the research on this has been done on cis male athletes. But she has general guidelines.

Abby: Typically research suggests that anywhere from 30 to 60 grams of carbohydrates per hour is where we should start. Typically, I say 40 to 60. Um, if it’s going to be three or more hours, it’s typically about 60 to 90 grams of carbs. And then there’s now new research where it’s like, if it’s even within that three or even four plus hour range, anywhere from 90 to 120 grams of carbs per hour is necessary and is showing to be actually more preventative in decreasing muscle fatigue and decreasing muscle breakdown, too.

Maren: For a half ironman triathlon like the one my partner is doing that will take six hours or more, we’re looking at upwards of 90 grams of carbs an hour. So with a little math, we can figure out that she’ll need to consume something like 600 grams of carbs during the race.

It’s hard to overstate just how much that is. 600 grams of carbs is what you’d find in about 82 Chips Ahoy chocolate chip cookies, 106 feet of Fruit by the Foot, 17 20-ounce gatorades, or 300 Heinz ketchup packets.

Yikes. It’s a lot of carbs. So you can see how important it is to choose something you want to eat. But it doesn’t have to be perfect. Any carbs are better than no carbs.

And there’s one more ingredient we need to add to this equation: electrolytes.

Alyssa: When we’re talking about electrolytes, we’re talking about sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium. And so a lot of times the main thing we’re looking at, especially for endurance sports is how much sodium are you getting in? And this is going to depend on the person, um, if someone’s a much heavier sweater versus not.

Maren: Electrolytes are crucial to the chemical reactions that cause your muscles to contract and relax. If your body has enough of them on hand, it will automatically balance these levels in the bloodstream to keep everything working, but if it runs too low on sodium, potassium, calcium, or magnesium, it can cause a bunch of problems, like muscle cramps and nutrient depletion.

But overall, sugar, salt, and water is all you need to make basic endurance fuel. It sounds pretty simple, but staring at the myriad hydration mixes, energy gels, and performance gummies at your local grocery store can quickly get overwhelming. So how do you choose? We’ll break it down, after this.

[advertisement]

Maren: Even if you think you know what to look for in your endurance fuel, the sports nutrition aisle at the grocery store can be daunting. But dietitian Abby Chan says that choosing what’s right for you really just comes down to three points.

Abby: First and foremost, what are you actually going to eat and want to eat when you don’t want to eat anything? So your preferences are going to be the most important. So if you’re going to have a goo that’s sitting in like your back pocket or in your running vest or something like that, and it’s going to sit there for months and it’s kind of just like a just in case thing, that’s probably not your preference. So I think preference is number one.

I think second is finances. Um, endurance sports are incredibly expensive, um, and they don’t have to be. I think a lot of times we’re told that like, you need to have this specific thing, you need to have this specific performance thing in order to compete and do well, and I would say that that’s actually wrong. You know, we, as humans, we’ve been doing endurance things for a long time and we can do it in a lot of different ways.

And then I think it leads into the third point. of like, what is your gastrointestinal tolerance, and what has your gastrointestinal training been, because that’s going to be the main indicator of if you succeed in an event or not.

Maren: You heard that right. Abby says that your gastrointestinal training, not your physical training, will be the biggest single factor in your success on race day. So let’s take the big three she outlined—what you want to eat, what you can afford, and what you can stomach—and build a gastrointestinal training plan. Because you really can train your gut to tolerate more nutrition over time, but you have to put in the effort.

Abby: My like main thing there is for people who have sensitive guts is like, you need to start fueling early and often.

Maren:which I think people might think is counterintuitive because they’re like, the second I start fueling, my stomach is going to hurt, so I’m going to put it off as long as possible. And I’m pretty sure that’s what my partner does.

Alyssa: I feel like that’s what a lot of people do.

Maren: It’s super common to be nauseated or experience other kinds of stomach upset when you’re doing intense, prolonged exercise. Remember that your body is pulling all the blood flow it can to your muscles, shunting it away from areas it deems less important like your stomach. And digestion requires blood flow, so without it, your stomach is left literally in the lurch. Food just sits there like a rock, and it’s not long before your body tries to find a way to get it out, one end or the other.

So, how do you train your gut to prevent this?

Abby: Just like your muscles, we need to start training our gut to being able to allocate those blood sources effectively so that we can actually digest and run or bike or do the thing we want to do.

Alyssa: I think that’s where it gets overwhelming for people like your partner, Maren, because it seems like sometimes going from like 0 to 100, I haven’t practiced this thing at all, like the skill of eating and it does pose like a fear risk, right? I don’t want to feel uncomfortable during this thing.

Maren: Doing a marathon would be terrifying if you’d never run anywhere close to that distance before, which is why you train up to it. The same is true with eating hundreds of grams of carbs while exercising. It can be intimidating if you’ve never done it before, but fueling is a skill you can learn. And the good news is that it’s much like any other kind of training: start early, start slow, and build up over time.

Maren: So, like, in terms of training your gut, would it be a good idea, if you’ve never done something like that before, to, like, bring a little pack of gummies with you on a run, even if it’s just a training run, even if it’s just, like, six miles or whatever, and just, like, eat one gummy every ten minutes or something like that? Like, is that how you start that? Or how do you go about that?

Alyssa: I would start in that situation. First, like moving that food. That pre-fueling closer and closer ,getting more confident with that. And then like doing something small maybe like right before your run or during right like with those gummies or during right with like Gatorade.

So kind of practicing moving that intake a little closer while simultaneously practicing like maybe a little bit of intake on my Like actual endurance sport,

So find something you enjoy and just start practicing eating that during your workouts. And it can be once a week if you’re feeling antsy and uncomfortable about the way that that’s going to make you feel. But if you can consistently do that for like one of your training sessions. For a week or two, then you can bring it up to two times a week and you can build that lived experience of knowing, Okay, I was hyping up in my head. This was gonna feel a certain way. It does not. Building that lived experience of your performance feeling better so you can feel confident enough to do it more frequently.

Maren: To begin your gastrointestinal training, you have to find what fuels work for you. Remember, your preferences are the most important thing, so it’s best to first start with what you want to eat and what you can afford.

Alyssa: There is so much variety. So like, if you’re talking about, let’s like go liquids first, right? Gatorade. The like other version of that, that would have some carbohydrate in it and have some liquid in it would be like some kind of juice. It’s going to be different. It’s not going to be exactly the same. You don’t get the electrolytes, but if you’re talking of a liquid thing that has carb in it, I would go juice. If you’re talking like the manufactured like chews or gummies, uh, gummy bears or like gummy worms or something like that, that you find really palatable.

Maren: I’ve noticed that in the rare instances my partner does eat while exercising, she often reaches for bananas, so I asked about fruit options.

Alyssa: Bananas or something that are a common thing you either see at races before or after, um, or a lot of people will use. And it’s because they have a good mixture of glucose and fructose. And typically because there’s a little bit more fiber, bananas can cause a little bit more gastrointestinal discomfort depending on how well you’ve trained your gut. Raisins are a great option too.

Maren: So, fruits and dried fruits are decent, but may actually not be the best place to start if you have an untrained stomach. There are other options besides candy, though.

Alyssa: Honey can be really great. It has some glucose, fructose, as well as some sucrose in it. Um, and it’s very similar to like a performance sport drink in the sugar compilation of it, which is great. Um, one thing you can do is you can add a little bit of salt to it. If you want to.

Maren: Juice, candy, honey, some fruits, these are all things you can get outside the sports nutrition aisle, and they may feel more approachable for some people, either for their palate or for their wallet. But what about those mysterious gels and gummies in the endurance fuel aisle? What makes those different?

What are the, like, bonuses, the pluses that you’re going to get from those really specifically engineered things. that you might not get from DIY fueling options or from like, quote unquote, “real food?”

Abby: That’s a great question. So if it’s, let’s even talk about gummies for a second because I often have a preference of Hi-Chews when I’m riding. Um, those are my favorite preferred like type of gummy thing. But what’s going to happen is if you have more of a store bought or like fruit gummy or candy or something like that, you are typically going to get about half of the amount of carbohydrates in the same amount of serving or volume. And typically either a half or two thirds less sodium in those.

So that’s going to be the thing that you’re really paying for is you’re paying for the engineering of this, like really great electrolyte balance. You’re paying for the engineering of having a solid amount of carbohydrates in it that you don’t have to carry this huge load with you. And also you may be paying for having some caffeine added in there as well.

Maren: Basically, if it’s marketed as endurance fuel, it’s probably going to get you more energy per ounce. It’s probably going to be more expensive, too.

Abby: If you’re training for, say it’s an Ironman or a Half Ironman, you’re going to have a whole year of training to get to that point.

And so, investing in all of these sports specific engineered foods that whole time, that’s a lot of money.

Maren: Abby says you can be thrifty by using mostly generic fuels during training, rather than expensive energy gels and drinks. Just make sure that as race-day approaches you start to incorporate the high-density, engineered foods that you’ll use during the race.

Alyssa: Race day is not the day to try like a new way of fueling yourself.

Maren: With Alyssa and Abby’s help, the fundamentals of endurance fueling were starting to come into focus. But much like running, which sounds easy in theory but is, in my experience, much more difficult in practice, how does all of this stuff translate to the real world?

To find out, I took my partner Kareena on a little shopping trip. First, we perused the energy drinks.

Maren: I think the problem here is that this one says one gram of sugar.

Kareena: Oh, that’s right. I want sugar.

Maren: Yeah. So, like, the ones that say, like, all of these say zero calories.

Kareena: Zero sugar.

Maren: Zero sugar. Like, those aren’t gonna help you.

Kareena: Yeah.

Maren: Even though they’re in the, like, health whatever. And this one says energy. And it’s got, like, what does it say?

Kareena: Caffeine.

Maren: Caffeine,

Next, the dried fruits section caught Kareena’s eye, with its health food store vibe and pictures of real fruits on the packages.

They did say raisins are not a bad one. Let’s see. 90 calories, 22 grams of carbs, and 2 grams of fiber. So, raisins is not bad.

Kareena: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

Maren: Okay. Maybe you would try?

Kareena: I would definitely try, yes.

Maren: Raisins? Yes. Okay

She still seemed hesitant, though, and we left the raisins on the shelf. But finally, we found something that got Kareena excited enough to try it out.

Like, okay, what about, like, Gushers?

Kareena: Oh my gosh.

Maren: What’s the nutritional value of Gushers? Okay, 18 grams of carbohydrates. No, one gram of fat.

Kareena: 40 of sodium.

Maren: 40 of sodium. That’s actually, that’s not bad.

Kareena: That’s so funny.

Maren: You could crush some gushers. You want to get some gushers?

Kareena: 100%.

Maren: Yes, let’s get some gushers. Oh my god.

Kareena: Wow.

Maren: Back in the car, gushers in hand, plus some sour patch watermelon, which I just wanted for myself but turns out are also not bad on the endurance fuel front, I asked Kareena how she was feeling.

Kareena: I’m a little excited. I think it’ll be good to finally be like responsible with my nutrition and I think it’s always felt a little too scary or unknown and now it’s like, oh no, it’s not so unknown or scary.

Maren: It’s just math.

Karen’s: Yeah, I love math. Who doesn’t love math?

Maren: Alright, let’s break into some of those gushers.

Kareena: Hell yeah.

Peter: Maren Larsen is a regular contributor to the Outside podcast.

Peter: Thank you to Kareena Tulloch for getting behind the mic, and to Abby Chan and Alyssa Moukheiber for sharing their nutritional knowledge.

Abby: You can find me, @ Abby, A-B-B-Y the R-D across all socials. And you can also find me at my website, evolveflg.com.

Alyssa: My Instagram is body peace, B-O-D-Y-P-E-A-C-E-R-D-N. So Body peace, RDN. And my website is alo, A-L-Onutrition.com, where there’s a bunch of dieticians who work with people with sports and food issues.

Maren: This episode was written and produced by Maren Larsen, and edited by me, Peter Frick-Wright. Music and sound design by Robbie Carver.

The Outside Podcast is made possible by our Outside Plus members. Learn more about all the benefits of membership at outsideonline.com slash pod plus.

Maren: I feel like we’re working kind of backwards because the last interview we did was about Post effort fueling, refueling, we were talking about hamburgers, which was so much fun. Now we’re talking about mid effort fueling, maybe in like another year I’ll call you to talk about pre fueling.

Abby: I would love that. That’d be so fun.

Alyssa: We’ll be ready.