He has largely proved right about Iraq and the broader Middle East.

Barton Swaim

Source link

He has largely proved right about Iraq and the broader Middle East.

Barton Swaim

Source link

Kyiv, Ukraine

If politics makes strange bedfellows, war sometimes makes strange career paths. In her 20s, Iryna Terekh was a “very artsy” architect who viewed the arms industry as “something destructive.” Now Ms. Terekh, 33, is chief technical officer and the public face of Fire Point, a Ukrainian defense company. She and her team developed the Flamingo, a long-range cruise missile that President Volodymyr Zelensky has called “our most successful missile.”

Copyright ©2025 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Jillian Kay Melchior

Source link

This is part of Reason‘s 2025 summer travel issue. Click here to read the rest of the issue.

The people of Georgia might well be the first folks who ever got properly wine-drunk.

Straddling the Promethean Caucasus mountains, wedged between both Black and Caspian seas, Georgia is a cultural crossroads between Europe and Asia. Its fertile valleys and slopes yielded the oldest archaeological evidence of wine production currently on record. During my short yet delightfully buzzed visit last fall, it was apparent that they’ve only gotten better at both the making and the drinking. Georgian winemaking traditions are hard won; in the Soviet era, many indigenous grape varieties were lost to brutish demands for quantity, not quality. Some families preserved precious varieties in secret.

I saw this heady spirit in the small town of Kachreti at the Burjanadze family home. At a traditional supra (banquet), my host and tomada (toastmaster) poured glass after glass of his own inky red Saperavi, each after a heartfelt toast, before bursting into a polyphonic song alongside his father. The wine came from a qvevri, a traditional clay pot submerged in his backyard, and the bottle’s label was stamped with his family’s fingerprints, several of whom shared the table and the cherished moment.

Georgia also gave the world one of the 20th century’s worst tyrants, Josef Stalin. Born in Gori, west of capital city Tbilisi, Stalin’s dark shadow lingers. Venture across the Kura River a few miles outside the city center and find yourself down a dank underground museum where a young revolutionary Stalin printed secret pamphlets during the Bolshevik Revolution. A charming yet perhaps contextually overeager docent asks you to sign a guest book scattered among USSR memorabilia.

Soviet-era grisliness aside, it’s an understatement to say Georgian politics have been complicated. Surrounded on all sides by great powers, the seismic situation encompasses many languages, plus the friction of competing political ideas and faiths in Armenia and Azerbaijan. Most notably it shares a contested border with Russia, the bear next door with an appetite.

If geography really is destiny, then the Georgian situation has understandably necessitated a stiff, perpetual drink.

After the Soviet Union’s collapse and at least a decade’s worth of post-Soviet corruption, a young Mikheil Saakashvili climbed Parliament’s stairs with flowers in hand. The Rose Revolution swept Saakashvili into office peacefully; he reduced government corruption and increased economic liberalization, spurred on by his libertarian-leaning minister of economy, Kakha Bendukidze. Georgia’s economy received a jolt, as if the whole country had taken a shot of its beloved brandy chacha (second only to the wine) and raised eyebrows in the Western world with the speed and success of those reforms.

Though Saakashvili left a mixed legacy (he’s now imprisoned on abuse of power charges), the stickiness of those free market ideas and reforms is notable, however fraught the country remains. Girchi, the only official libertarian party in a post-Soviet state outside of Russia, was formed by dissenters from Saakashvili’s United National Movement party after his collapse. It has since advocated both economic and drug liberalization, while staging stunts against conscription and state crackdowns on sex workers, going so far as opening a brothel in its party headquarters.

Georgia remains a swirl of political foment, as I realized by stumbling accidentally onto Rustaveli Avenue before fall parliamentary elections. Thousands of Georgians paraded, draped in Georgian and European Union colors, marching in support of then-President Salome Zourabichvili, as she tried to hold off billionaire and former Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream party. Ivanishvili’s ties to Russia and presence in politics still loom large, much like his Bond villain–esque mansion perched high above Tbilisi.

Despite the turbulence, pockets of Tbilisi buzz with young entrepreneurs reclaiming and redefining the Georgian trajectory, one pointed decidedly west. Down an unassuming street, there’s Lasha Devdariani selling handcrafted silk robes from his cozy studio, some of which cloaked Tilda Swinton in Only Lovers Left Alive. Walk into Sololaki where traditional meets modern at Iasamani restaurant—bare candles burning over peeling paint, cracked tiles, and khachapuri hint at the history of both the room and the nation. Around the corner the gents at 41 Degrees Art of Drinks sling cocktails from a handwritten book that taste like the throng on Rustaveli Avenue felt: fiery and self–assured.

John Steinbeck heard of Georgia’s magic before arriving in 1947 at the start of the Cold War. In A Russian Journal,he noted: “People who had never been there and possibly never could go there spoke of Georgia with a kind of longing and great admiration. They spoke of Georgians as supermen, as great drinkers, great dancers, great musicians, great workers and lovers. And they spoke of the country in the Caucasus and around the Black Sea as a kind of second heaven.”

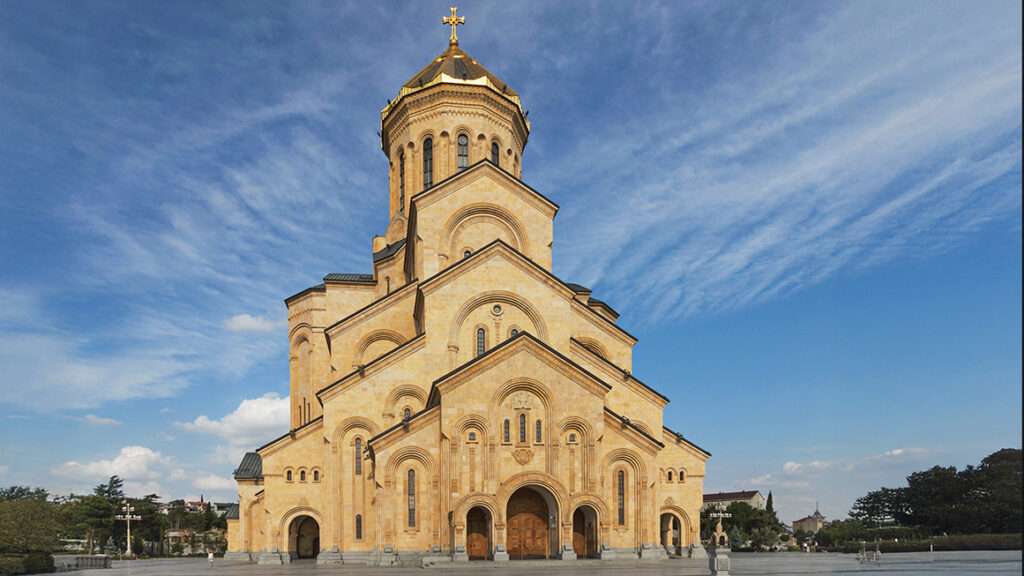

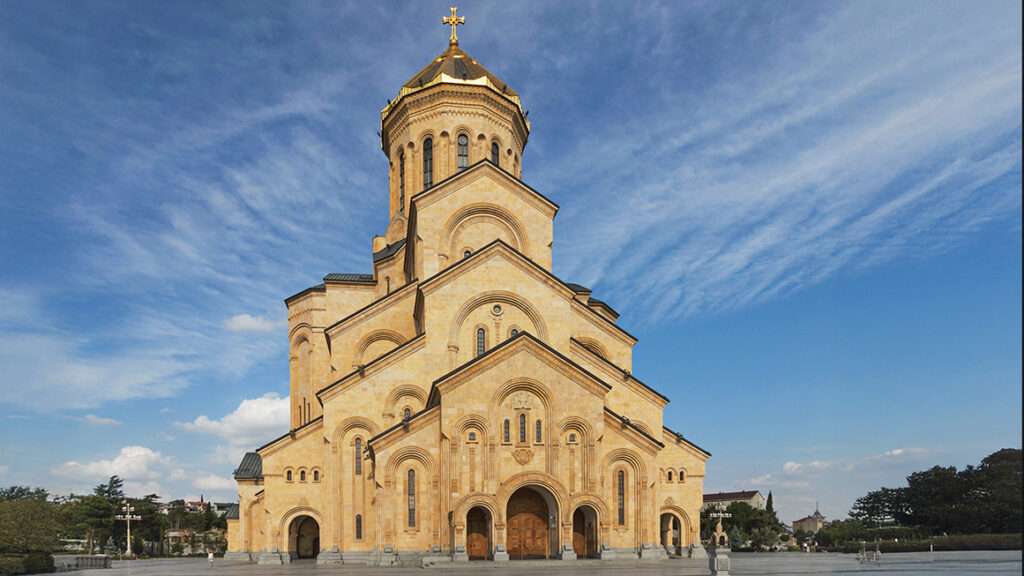

More people, especially free thinkers and drinkers, should visit. Drink the wine, pet the dogs (tagged strays roam lazily, freely, even into bars and hotel lobbies), shoot the chacha, stare at giant Jesus in Holy Trinity Cathedral, devour khinkali (hands only), and let the hospitality intoxicate you in its distinctly Georgian way.

It’s best to have a car to see Georgia at your own pace. Pick up a rental and head to your hotel.

Stay in Tbilisi for three nights.

Start your adventure by getting a feel for Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi. This is a place where the old meets the new, offering a mix of historic sites and trendy bars and restaurants.

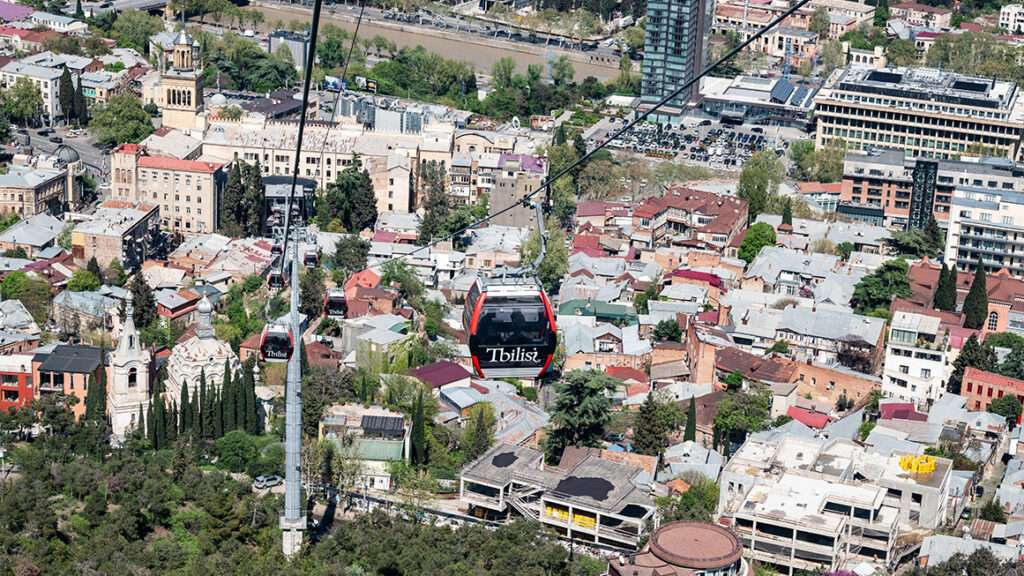

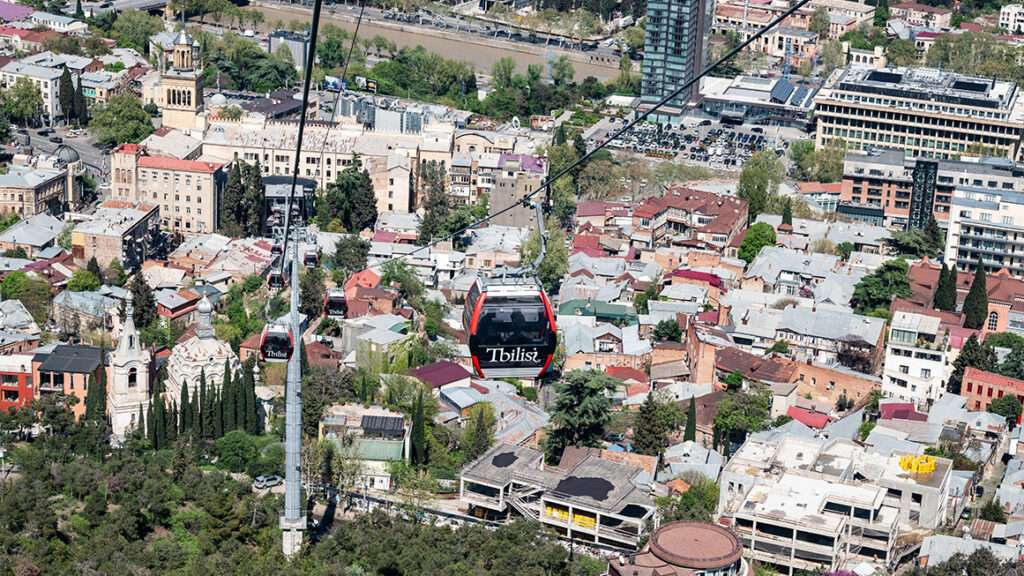

The Holy Trinity Cathedral of Tbilisi is the largest Orthodox church in Georgia and boasts fantastic views of the city. Next, take the Tbilisi Funicular up to Mtatsminda Pantheon, where some of Georgia’s most prominent writers, artists, and national heroes are buried. Up there, you can enjoy Mtatsminda Park and get a view of former Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili’s stunning house. Take the Rustaveli-Mtatsminda Cable Car back down the hill to end the trip.

Go where the wind blows today, and be sure to drink some wine along the way.

Optional activities: 8000 Vintages wine shop and bar, Cafe Daphna, Dry Bridge Market, Queen Darejan Palace, Tbilisi State Academy of Arts, the National Gallery, Underground Printing House Museum

Head east for your two-hour drive to Sighnaghi, known as “the city of love” and located in the heart of Georgia’s wine region. Revel in the colorful buildings, the medieval architecture, and the stunning Caucasus mountains on the horizon. And of course, the wine. Visit the Kerovani Winery to sample an assortment of Georgian wines and learn about the traditional Kakhetian method of winemaking in qvevri (clay vessels).

Stay in Sighnaghi for two nights.

Enjoy your final day in Georgia!

Optional activities: Sighnagi National Museum, St. George Church, Marriage Palace, The Sighnaghi World War II Memorial, Sighnaghi Wall

Drive back to Tbilisi for your return flight home.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline “The Possible Birthplace of Wine and Definite Birthplace of Stalin.”

Hunt Beaty

Source link

WASHINGTON (AP) — The actor in the viral music video denouncing the 2024 Olympics looks a lot like French President Emmanuel Macron. The images of rats, trash and the sewage, however, were dreamed up by artificial intelligence.

Portraying Paris as a crime-ridden cesspool, the video mocking the Games spread quickly on social media platforms like YouTube and X, helped on its way by 30,000 social media bots linked to a notorious Russian disinformation group that has set its sights on France before. Within days, the video was available in 13 languages, thanks to quick translation by AI.

“Paris, Paris, 1-2-3, go to Seine and make a pee,” taunts an AI-enhanced singer as the faux Macron actor dances in the background, seemingly a reference to water quality concerns in the Seine River where some competitions are taking place.

Moscow is making its presence felt during the Paris Games, with groups linked to Russia’s government using online disinformation and state propaganda to spread incendiary claims and attack the host country — showing how global events like the Olympics are now high-profile targets for online disinformation and propaganda.

Over the weekend, disinformation networks linked to the Kremlin seized on a divide over Algerian boxer Imane Khelif, who has faced unsubstantiated questions about her gender. Baseless claims that she is a man or transgender surfaced after a controversial boxing association with Russian ties said she failed an opaque eligibility test before last year’s world boxing championships.

Russian networks amplified the debate, which quickly became a trending topic online. British news outlets, author J.K. Rowling and right-wing politicians like Donald Trump added to the deluge. At its height late last week, X users were posting about the boxer tens of thousands of times per hour, according to an analysis by PeakMetrics, a cyber firm that tracks online narratives.

The boxing group at the root of the claims — the International Boxing Association — has been permanently barred from the Olympics, has a Russian president who is an ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin and its biggest sponsor is the state energy company Gazprom. Questions also have surfaced about its decision to disqualify Khelif last year after she had beaten a Russian boxer.

Approving only a small number of Russian athletes to compete as neutrals and banning them from team sports following the invasion of Ukraine all but guaranteed the Kremlin’s response, said Gordon Crovitz, co-founder of NewsGuard, a firm that analyzes online misinformation. NewsGuard has tracked dozens of examples of disinformation targeting the Paris Games, including the fake music video.

Russia’s disinformation campaign targeting the Olympics stands out for its technical skill, Crovitz said.

“What’s different now is that they are perhaps the most advanced users of generative AI models for malign purposes: fake videos, fake music, fake websites,” he said.

AI can be used to create lifelike images, audio and video, rapidly translate text and generate culturally specific content that sounds and reads like it was created by a human. The once labor-intensive work of creating fake social media accounts or websites and writing conversational posts can now be done quickly and cheaply.

Another video amplified by accounts based in Russia in recent weeks claimed the CIA and U.S. State Department warned Americans not to use the Paris metro. No such warning was issued.

Russian state media has trumpeted some of the same false and misleading content. Instead of covering the athletic competitions, much of the coverage of the Olympics has focused on crime, immigration, litter and pollution.

One article in the state-run Sputnik news service summed it up: “These Paris ‘games’ sure are going swimmingly. Here’s an idea. Stop awarding the Olympics to the decadent, rotting west.”

Russia has used propaganda to disparage past Olympics, as it did when the then-Soviet Union boycotted the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. At the time, it distributed printed material to Olympic officials in Africa and Asia suggesting that non-white athletes would be hunted by racists in the U.S., according to an analysis from Microsoft Threat Intelligence, a unit within the technology company that studies malicious online actors.

Russia also has targeted past Olympic Games with cyberattacks.

“If they cannot participate in or win the Games, then they seek to undercut, defame, and degrade the international competition in the minds of participants, spectators, and global audiences,” analysts at Microsoft concluded.

A message left with the Russian government was not immediately returned on Monday.

Authorities in France have been on high alert for sabotage, cyberattacks or disinformation targeting the Games. A 40-year-old Russian man was arrested in France last month and charged with working for a foreign power to destabilize the European country ahead of the Games.

Other nations, criminal groups, extremist organizations and scam artists also are exploiting the Olympics to spread their own disinformation. Any global event like the Olympics — or a climate disaster or big election — that draws a lot of people online is likely to generate similar amounts of false and misleading claims, said Mark Calandra, executive vice president at CSC Digital Brand Services, a firm that tracks fraudulent activity online.

CSC’s researchers noticed a sharp increase in fake website domain names being registered ahead of the Olympics. In many cases, groups set up sites that appear to provide Olympic content, or sell Olympic merchandise.

Instead, they’re designed to collect information on the user. Sometimes it’s a scam artist looking to steal personal financial data. In others, the sites are used by foreign governments to collect information on Americans — or as a way to spread more disinformation.

“Bad actors look for these global events,” Calandra said. “Whether they’re positive events like the Olympics or more concerning ones, these people use everyone’s heightened awareness and interest to try to exploit them.”

TALLINN, Estonia (AP) — Watching the Paris Olympics will be difficult for most people in Russia — and in the view of its media, it’s not really worth the effort.

Only 15 Russian citizens will be competing in the Games and, in principle, they won’t be representing Russia. Because Russia and neighboring Belarus were banned from fielding national teams because of the war in Ukraine, Russian and Belarusian athletes approved to compete will be doing so as neutrals.

Russians have been intense Olympics fans since the days when the Soviet Union’s sports prowess was nicknamed “The Big Red Machine.” But with so few of their countrymen competing, Russia’s state TV channels aren’t broadcasting any of the events. Russians may find feeds online, but could need a virtual private network to circumvent the country’s block of some channels.

The last time the Olympics weren’t on TV in Russia — which has won the second-largest number of medals, counting the Soviet era — was in 1984, when the Soviet Union boycotted the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

State news channel Rossiya 24 did broadcast a report from Paris on the opening ceremony Friday night, showing dancing and plumes of colored smoke rising over the Seine River. News agencies Tass and RIA-Novosti gave it glancing attention, with terse stories saying the opening ceremony had begun, but little detail other than noting the rain drove many spectators away.

Newspapers aren’t ignoring the Olympics entirely, but their main approach has been to accentuate the negative, writing at length about crime in Paris, the inconvenience of barricades placed throughout the city and reported food shortages for athletes.

“The Paris Olympics is an amazing event, if not to say a phenomenon: Competitions in individual disciplines have just just started, the opening ceremony has not even taken place, and so many scandals have already accumulated that they will be enough for several Games,” Sovietsky Sport newspaper reporter Alexander Shulgin wrote Thursday.

“I think that this Olympics will go down in history with a completely negative result,” the newspaper Sport-Ekspress quoted Irina Rodnina, a three-time figure skating gold winner and now a member of the Russian parliament, as saying.

A whiff of schadenfreude floats through many of the stories. Writing about the fences and barriers erected in Paris, Sovietsky Sport’s Andrei Tupikov said: “Once upon a time, everyone pointed their finger at the structure of sports competitions in Russia. Many did not like the fact that before any mass events there were too many different fences and barriers around the arenas and stadiums. … In our reality the practice is slowly fading away, but in Europe it is being actively adopted.”

Shulgin, seemingly smarting from criticism about the facilities at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, suggested Paris may face an opening ceremony embarrassment similar to Sochi’s, when a display of the Olympic rings malfunctioned.

“If the ring did not open in Sochi, it’s scary to imagine what could happen in Paris,” he wrote, but did not follow up after the ceremony.

No such disaster occurred, but Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova on Saturday compared Paris unfavorably to Sochi.

“The Western media did not like (stray) dogs at the Sochi Games. In Paris, they were smiled at by the rats that flooded the city streets,” she said in a statement. She also called the opening ceremony “ridiculous.”

Commentary on the Paris Games also verged into ethical and philosophical questions, such as whether one should root for the few Russians participating despite the national team’s exclusion. To receive approval from the International Olympic Committee, the athletes cannot have demonstrated support for the Russian invasion of Ukraine, among other stipulations.

Sport-Ekspress commentator Oleg Shamonaev analyzed the connotations of each word in the Individual Neutral Athlete designation and concluded: “The 15 ‘neutrals’ with a Russian passport who did not change their flag, despite 2 1/2 years of sanctions … are worthy not of condemnation but of respect.”

“It’s stupid to pretend we don’t care about what happens to them at the 2024 Games,” he said.

For more coverage of the Paris Olympics, visit https://apnews.com/hub/2024-paris-olympic-games.

Today is the 100th anniversary of the death of Vladimir Lenin, the first leader of the Soviet Union, the world’s first communist state. While Lenin’s successor Joseph Stalin has few modern Western defenders (even as the current Russian government has tried to rehabilitate him), Lenin still has many admirers among Western leftists. They tend to ignore the great evil he did or blame it on Stalin.

Nothing can be further from the truth. Most of the cruel oppressive features of Soviet totalitarianism actually began under Lenin. Stalin merely perpetuated them on a larger scale.

Let’s take a little history quiz. Which of the following features of the Soviet state were first introduced under Lenin, and which by Stalin:

1. The Gulag system of slave labor camps

2. The Cheka (secret police agency eventually known as the KGB)

3. Collectivization of agriculture leading to mass famines

4. Mass executions with little or no due process

5. A one-party state, with bans on all opposition parties (including socialist ones)

6. Suppression of freedom of speech and religion

7. Confiscation of private businesses, including even small businesses

8. Invading other nations in order to spread communism there

9. State control of the media for purposes of promoting regime propaganda, and preventing distribution of opposition speech

If you answered Lenin, you were correct in every case! And virtually every one of these measures was also supported by Trotsky, Bukharin, and other Bolshevik leaders whom some Western leftists like to trumpet as potentially superior alternatives to Stalin. Had Trotsky rather than Stalin come to power after Lenin’s death, he would have happily continued all of the above, and in some cases doubled down on it.

Policies 3 and 7 on this list were partially suspended or reversed under Lenin’s New Economic Policy, beginning in 1921. But Lenin and other Soviet leaders were always clear that this was just a temporary expedient they intended to reverse as soon as possible.

The late Harvard historian Richard Pipes has an excellent overview of Lenin’s oppressive policies and their consequences in his book Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime.

It’s also worth noting that Lenin was the one who elevated Stalin to the position of General Secretary of the Communist Party, thereby greatly increasing the likelihood that Stalin would ultimately succeed him. It’s unlikely Lenin would have done that if the two men had major disagreements on ideology and policy.

Did Stalin engage in any new forms of repression? Yes, as a matter of fact, he did:

1. Deportation of entire ethnic groups (most notably the Crimean Tatars). I doubt Lenin would have had scruples about this if he thought it might be useful. But he didn’t actually do it, at least not on a large scale.

2. State-sponsored anti-Semitism. There was no shortage of anti-Semitism in Lenin’s USSR. But Lenin didn’t actively promote it and probably wasn’t an anti-Semite himself. He even occasionally condemned anti-Semitism. On this issue, Stalin was much worse.

3. Large-scale purges of loyal communists. Lenin never did this, and Trotsky probably would not have had he come to power. This is the Stalinist policy that most alienated many Western leftists. How dare Stalin kill communist heroes like Trotsky, Bukharin, and others? But it was among the least of Stalin’s crimes. Many of Stalin’s communist victims were actually brutal oppressors themselves, and arguably got what they deserved (albeit, for the wrong reasons, and without due process). In fairness, Stalin also purged a lot of communists who weren’t actively involved in repression, but just joined the Party to advance their careers (you can say the same thing about many Germans who joined the Nazi Party after it came to power).

If you add it all up, Lenin was the one who initiated the policies that caused about 90% of the repression and death in the Soviet Union. And these ideas weren’t idiosyncratic to Lenin. They were backed by the vast majority of other communist leaders, as well, which is why later communist regimes tended to adopt similar policies to those of the Soviet Union and got similar results. Mao Zedong managed to exceed the Soviet Union in sheer numbers of victims (he had a much larger population to work with). Cambodia’s Pol Pot killed a higher percentage of his population in a shorter period of time, and arguably managed to exceed both the Soviets and Chinese in sheer torture and cruelty. But these mass murderers were, on major issues, still largely following the model first established by Lenin.

With a few notable exceptions listed above, Stalin mostly just continued and expanded Lenin’s evil policies. Ultimately, the root of the evil here wasn’t the personality of any one leader, but the ideology Lenin, Stalin, and their comrades all sought to implement. But Lenin was nonetheless notable for being the first to lead a regime that pursued these policies, and set an example for all that followed. That is how we should remember him.

Ilya Somin

Source link

Press play to listen to this article

Voiced by artificial intelligence.

LONDON — In May last year, my phone buzzed with a message from a contact in the British parliament whom I know well.

We meet every so often for coffee in a cafe far away enough from Westminster to be discreet, where he tells me what’s unfolding in the depths of parliament’s dingy corridors.

That day, his message read: “Has an MP been arrested today? Who can say?”

His first question was a news tip for me to follow up on. I began ringing and texting everyone I knew who might be able to tell me about the possible detention of a member of parliament.

Sure enough, the police soon confirmed that a 56-year-old man had been arrested on suspicion of rape and other offenses.

My contact’s second question — “Who can say?” — was more complicated.

In the hours after the arrest, pretty much every British political media organization prominently reported the man’s arrest, together with his age, his position as an MP, and his alleged crimes.

But while every reporter in Westminster knew exactly who he was, it took more than a year before anybody dared publish his name.

As with many other matters of the public interest, Britain’s restrictive libel and privacy laws put any publication that reported his identity at risk of a lengthy legal battle and crippling financial penalties.

In July, London’s Sunday Times took the decision to name him, reporting that he had been absent from parliament since his arrest. With the exception of a single mention in the Mirror newspaper, no other mainstream publication followed suit.

POLITICO can now join in reporting that the man arrested is Andrew Rosindell, a member of the Conservative party who has served as MP for the constituency of Romford in Essex, east of London, since 2001.

Rosindell has not been charged and denies any wrongdoing. He, like every British citizen, is entitled to the presumption of innocence. He has been released by police while they look into his case.

But POLITICO believes there is a clear public interest in naming him, given the obvious impact upon his ability to represent his constituents — and because of further information we publish today about his activities since May 2021.

During the time he has been absent from parliament, he has continued to claim expenses for his work there and accepted foreign trips worth £8,548 (nearly $11,000) to Bahrain, India, Italy and Poland. He has also continued to receive donations from his supporters.

Rosindell declined to comment for this article.

These might seem like obvious and easy facts to report. But doing so has required extensive discussions with my editors and with a lawyer, even after the courage shown by the Sunday Times.

The Rosindell case is a clear-cut example — one among many — of how Britain’s media laws sometimes place individual privacy over the public interest, putting obstacles in the way of accountability journalism.

Given the work involved in reporting something like the allegations against Rosindell, it’s easy to see how many editors and reporters — battling for readers while grinding out the news — might look at the facts involved and conclude writing about it is simply not worth the risk.

For journalists trying to keep public figures honest, this can be a serious problem — and it’s one the United Kingdom is exporting around the world.

The heart of the challenge lies in England’s incredibly tough defamation laws — which penalize statements that could damage someone’s public image among “right-thinking members of society” or cause “serious harm” to their reputation.

In the United States, journalists are not only shielded by the First Amendment, but for a defamation claim to succeed, the claimant must prove the allegations are false and were disseminated with malicious intent.

In English courts, the burden of proof lies on the publisher of the potentially libelous statement. Truth can be a defense, but you need to have the actual goods; simply pointing to another press report or even relying on allegations in a police arrest warrant, for example, is not enough.

In recent years, these defamation laws have combined with court rulings on the privacy of individuals under arrest or investigation to hinder reporting on potential abuses of power and other matters of the public interest.

This has contributed to the prevalence of “open secrets” in British public life: individuals known within their circles for alleged wrongdoing who cannot be named due to the onerously high burden of legal proof.

A recent example of this is the allegations against the comedian Russell Brand. When the Sunday Times published an investigation into claims of sexual abuse against him, many in the television industry responded that this had been known for as long as he had been famous.

The trouble was, as the Daily Mail detailed, that for years Brand had deployed lawyers to use legal threats to shoot down stories or rumblings of stories that might crop up about his behavior.

Scratch a high-profile scandal, and you’re likely to find a host of lawyers looking to block reporting about it, or seeking damages for what’s already been published.

The actor and producer Noel Clarke is suing the Guardian over a series of articles reporting allegations of sexual assault and harassment, which, even if unsuccessful, is likely to cost the newspaper hundreds of thousands of pounds.

A well-known British business is suing a broadcaster over an investigation into their working practices that has not yet been aired.

Complainants don’t even have to win for their lawsuits to have a chilling effect. Successfully fending off a claim can eat up months or years of a journalist’s time, if they have the resources at all to fight it.

Even the threat of a lawsuit can be enough to give many journalists pause.

When Ben De Pear was editor of Channel 4 News, the broadcaster worked with the Guardian and New York Times to expose the collection of Facebook users’ personal data by the consulting firm Cambridge Analytica for use in the 2016 Brexit referendum campaign.

After the journalists reached out for comment from Facebook, they were met with a barrage of different tactics, he said. “They didn’t answer till the last possible minute. Their response was published and sent to news organizations before it was sent to us. They prevaricated. Their lawyers sometimes sent 30 or 40 pages of legalese.”

“Normally, the longer the response, the less there is in it,” he added. “Good lawyers, journalists and editors will be able to cut through that, but it still sucks up time and causes an inordinate amount of stress.”

So common have efforts by rich individuals and companies to squash stories become that the practice has been endowed with an acronym: SLAPPs, or strategic lawsuits against public participation.

The problem isn’t constrained to local shores; England’s libel laws are increasingly being deployed against reporting in foreign countries about foreign individuals — a practice detractors describe as “libel tourism.”

Claimants have to establish jurisdiction to bring their action in the U.K., but the threshold is “not a very onerous one,” said Padraig Hughes, legal director at the Media Legal Defense Initiative, a London nonprofit offering advice and financial support to journalists facing defamation claims.

Journalists Tom Burgis and Catherine Belton were both sued over books they wrote about Russian President Vladimir Putin’s regime and corruption in the former Soviet Union.

Burgis and Belton both won, but their experiences don’t tell the whole story, said Clare Rewcastle Brown, a British journalist who helped expose one of the largest ever corruption scandals: the looting of billions of dollars from Malaysia’s 1MDB sovereign wealth fund.

“For every showcase where publishers can boast that they stuck with the author — and well done them — the fact of the matter is, they’ll have killed numerous other books,” she said.

My call with Rewcastle Brown was arranged around her schedule of getting up at 3 a.m. to appear via Zoom as a defendant in a defamation action brought against her by a member of the Malaysian royal family — one of dozens of similar actions she has faced.

She tells me she has survived through sheer bloody-mindedness, and by “frankly, having nothing to lose.”

She acknowledged that for many media outlets, especially smaller ones, these types of attacks could cause them to re-evaluate whether the efforts are worth it.

“As the money starts to ebb, the courage likewise ebbs away,” she said.

England’s media laws do have their defenders, and there are examples where the system has made a positive difference. It “serves to make journalism in this country very rigorous, so it does have a good effect,” is how De Pear, of Channel 4 News, put it.

Gavin Phillipson, a professor of law at Bristol University, pointed out that the U.S. is not a model but an exception, with English law “completely in line with the vast majority of liberal democracies in both Europe and the Commonwealth.”

He has written about the “devastating effect” of stories such as the Mail Online’s decision to name a young Muslim man arrested in connection with the 2017 Manchester arena bombing. He was innocent and released without charge, but his name had already spread across the world in connection with the atrocity.

Phillipson notes that while the courts have established that everyone should have a reasonable expectation of privacy, “it doesn’t cover the underlying conduct itself.”

“If the press do their own investigative journalism and find out what actually has happened, then the law of privacy doesn’t stop them publishing that,” he said.

This factored into POLITICO’s decision to publish sexual harassment allegations against Julian Knight, a senior member of parliament, early this year.

Our story relied on our reporting, not just the fact that he’s being investigated by police. (Knight strongly denies all the allegations against him.)

Some in the U.K. have recognized the problem and made efforts to stamp down on libel tourism.

The Defamation Act 2013 raised the bar so that claimants would have to show they had suffered “serious” harm to their reputation, and introduced tighter rules for litigants not domiciled in the U.K.

The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act attempted to give extra protection to defendants in litigation related to economic crimes. And this year the government announced legislation to scrap a rule forcing media companies to pay the legal bills of people who sue them.

But the pendulum has also swung the other way.

There was until recently a rule that the police had to notify the House of Commons Speaker of the arrest of any member of parliament and their name would be published.

If this measure had still been in place, it would have made the debate about publishing Rosindell’s name moot. But MPs opted to scrap it with very little fanfare in 2016.

Gabriel Pogrund, Whitehall editor for the Sunday Times, wrote the newspaper’s story naming Rosindell. He also reported on an accusation of rape against the former MP Charlie Elphicke, over which Elphicke sued the paper. (Elphicke was later convicted of sexual assault and dropped his claim.)

Pogrund argues that his job has gotten harder as a string of recent legal defeats for publications has diminished the appetite for testing where the line is.

The result, when it comes to public figures and organizations suspected of serious wrongdoing, he said, has been “an informal conspiracy of silence.”

Dan Bloom contributed reporting.

Esther Webber

Source link

The Kremlin’s spy chief Sergei Naryshkin warned the U.S. that Ukraine will turn into its “second Vietnam,” amid disagreement in Congress over funding for Kyiv.

“Ukraine will turn into a ‘black hole’ absorbing more and more resources and people,” Russian foreign intelligence chief Naryshkin said Thursday in a written statement published by his agency’s house journal, the Intelligence Operative.

“Ultimately, the U.S. risks creating a ‘second Vietnam’ for itself, and every new American administration will have to deal with it,” he added.

The warning comes after U.S. President Joe Biden on Wednesday urged Congress to further support Ukraine with funding. “We can’t let Putin win,” Biden said.

Biden is trying to push through a $61.4 billion emergency funding request for Kyiv, but opposition against further aid to Ukraine has grown among Republicans in the House of Representatives.

The U.S. was engaged in the Vietnam War — fought between South Vietnam and the U.S. on one side and communist North Vietnam backed by the Soviet Union and China on the other — for nearly two decades. The conflict claimed more than a million lives, including tens of thousands from the U.S., and ended with a comprehensive victory for the North Vietnamese forces.

According to a recent poll, 59 percent of Americans still support sending military aid to Ukraine.

Laura Hülsemann

Source link

BERLIN — Facing war on two fronts — in Ukraine and in the Middle East — Kyiv is calling on Western democracies to ramp up investment in weapons, saying that arms factory output worldwide is falling miles short of what is needed.

In an interview, Ukraine’s Minister for Strategic Industries Oleksandr Kamyshin told POLITICO Western countries needed to accelerate production of missiles, shells and military drones as close to frontlines as possible.

“The free world should be producing enough to protect itself,” Kamyshin said, on a mission to the German capital to persuade arms producers to invest in war-ravaged Ukraine. “That’s why we have to produce more and better weapons to stay safe.”

Current factory capacity was woeful, he argued. “If you get together all the worldwide capacities for weapons production, for ammunition production, that will be not enough for this war,” said Kamyshin of the state of play along Ukraine’s more than 1,000 kilometers of active frontline.

As the Israel Defense Forces continue to pummel Gaza and fighting gathers pace along the contact line in Ukraine, armies are burning through ammunition at a rate not seen in decades. Policymakers are asking whether Western allies can support both countries with air defense systems and artillery at once.

The answer, says Kamyshin, is to start building out production facilities now. “What happens in Israel now shows and proves that the defense industry globally is a destination for investments for decades,” he said.

Since Russia’s war on Ukraine started in February 2022, western governments have been funneling arms to Kyiv. That includes hundreds of thousands of artillery rounds, armored vehicles and other equipment.

But as the grind of war continues, Kyiv has changed tack — appointing Kamyshin, the former boss of Ukraine’s state railway — to the post of minister for strategic industries. Ukraine, formerly a major military hub in the Soviet Union, is now trying to increase output of armored vehicles, ammunition and air defense systems, he said, and wants Western partners to invest.

A key step is expected on Tuesday, when German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal will announce a new joint venture between Rheinmetall and Ukroboronprom, a Ukrainian defense company, Kamyshin said.

In late September, Germany’s Federal Cartel Office gave the green light to the cooperation agreement after a review that found the proposed venture “does not result in any overlaps in terms of competition in Germany.”

Last March, EU countries pledged to send a million artillery rounds to Ukraine over the following year as part of a program to lift production. Ukraine may need as much as 1.5 million shells annually to sustain its war effort, a daunting task that Kamyshin hopes he can help, at least partially, with domestic output.

In total, Ukraine has received over 350 self-propelled and towed artillery systems from NATO countries and Australia. Combined with Soviet-era pieces in Ukrainian stocks prior to the Russian invasion, Kyiv has approximately 1,600 pieces of artillery in service — but must cover a massive front.

And although the deepening of the German-Ukrainian defense relationship is a boon for Kyiv’s war effort, the enemy on the battlefield — Russia — can also leverage its own international relationships for war materiel, and has been quick to agree military hardware deals with the likes of Iran and North Korea.

Earlier this month, reports pointed out Pyongyang likely transferred a sizable shipment of artillery ammunition to Russia. The details of the deal are secret, but the shipment came on the heels of a visit to Pyongyang by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. North Korean leader Kim Jong Un in turn made a trip to Russia by rail and met with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Russia previously struck a deal with Tehran for Iranian loitering munitions that hammered cities across Ukraine last winter in an intentional targeting of civilian infrastructure.

The increasingly international scope of sourcing for the war in Ukraine is not limited to non-NATO countries. Poland recently started taking delivery of tanks, howitzers, rocket launchers and light attack aircraft from South Korea, a nod to how quickly Seoul can ramp up production affordably.

For Kamyshin, the key was to make plans for the long term.

“This war can be for decades,” he said. “[The] Russians can come back always.”

Joshua Posaner and Caleb Larson

Source link

Press play to listen to this article

Voiced by artificial intelligence.

Top officials from the United States and the EU met with their Russian counterparts for undisclosed emergency talks in Turkey designed to resolve the standoff over Nagorno-Karabakh, just days before Azerbaijan launched a military offensive last month to seize the breakaway territory from ethnic Armenian control.

The off-diary meeting marks a rare — if ultimately unsuccessful — contact between Moscow and the West on a major security concern, after Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 upended regular diplomacy.

A senior diplomat with knowledge of the discussions told POLITICO the meeting took place on September 17 in Istanbul as part of efforts to pressure Azerbaijan to end its nine-month blockade of the enclave and allow in humanitarian aid convoys from Armenia. According to the envoy, the meeting focused on “how to get the bloody trucks moving” and ensure supplies of food and fuel could reach its estimated 100,000 residents.

The U.S. was represented by Louis Bono, Washington’s senior adviser for Caucasus negotiations, while the EU dispatched Toivo Klaar, its representative for the region. Russia, meanwhile, sent Igor Khovaev, who serves as Putin’s special envoy on relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Such high-level diplomatic interaction is rare. In March, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov came face to face on the sidelines of the G20 meeting in India — but Moscow insisted the exchange happened “on the move” and no negotiations were held.

In a statement provided to POLITICO, an EU official said “we believe it is important to maintain channels of communications with relevant interlocutors to avoid misunderstandings.” The official also observed Klaar had sought to keep lines open on numerous fronts over the “past years,” including in talks with Khovaev and Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Galuzin.

A spokesperson for the U.S. State Department declined to comment on the meeting, saying only that “we do not comment on private diplomatic discussions.”

However, a U.S. official familiar with the matter who was granted anonymity to discuss sensitive diplomatic matters explained the discussions came out of an understanding that the Kremlin still holds sway in the region. “We need to be able to work with the Russians on this because they do have influence over the parties, especially as we’re at a precarious moment right now,” the American official said.

Azerbaijan launched a lightning offensive against Nagorno-Karabakh on September 19, sending tanks and troops into the region under the cover of heavy artillery bombardment. Karabakh Armenian leaders were forced to surrender following 24 hours of fierce fighting that killed hundreds on both sides. Since then, the Armenian government says more than 100,000 people have fled their homes and crossed the border, fearing for their lives.

Azerbaijan insists it has the right to take action against “illegal armed formations” on its internationally recognized territory, and has pledged to “reintegrate” those who have stayed behind. European Council President Charles Michel described the military operation as “devastating,” while Blinken has joined calls for Azerbaijan “to refrain from further hostilities in Nagorno-Karabakh and provide unhindered humanitarian access.”

Nahal Toosi, Gabriel Gavin and Eric Bazail-Eimil

Source link

Press play to listen to this article

Voiced by artificial intelligence.

Fierce firefights and heavy shelling echo once again around the mountains of Nagorno-Karabakh, an isolated region at the very edge of Europe that has seen several major wars since the fall of the Soviet Union.

On Tuesday, the South Caucasus nation of Azerbaijan announced its armed forces launched “local anti-terrorist activities” in Nagorno-Karabakh, which is inside Azerbaijan’s borders but is controlled as a breakaway state by its ethnic Armenian population.

Now, with fighting raging and allegations of an impending “genocide” reaching fever pitch, all eyes are on the decades-old conflict that threatens to draw in some of the world’s leading military powers.

For weeks, Armenia and international observers have warned that Azerbaijan was massing its armed forces along the heavily fortified line of contact in Nagorno-Karabakh, preparing to stage an offensive against local ethnic Armenian troops. Clips shared online showed Azerbaijani vehicles daubed with an upside-down ‘A’-symbol, reminiscent of the ‘Z’ sign painted onto Russian vehicles ahead of the invasion of Ukraine last year.

In the early hours of Tuesday, Karabakh Armenian officials reported a major offensive by Azerbaijan was underway, with air raid sirens sounding in Stepankert, the de facto capital. The region’s estimated 100,000 residents have been told by Azerbaijan to “evacuate” via “humanitarian corridors” leading to Armenia. However, Azerbaijani forces control all of the entry and exit points and many locals fear they will not be allowed to pass safely.

Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s top foreign policy advisor, Hikmet Hajiyev, insisted to POLITICO the “goal is to neutralize military infrastructure” and denied civilians were being targeted. However, unverified photographs posted online appear to show damaged apartment buildings, and the Karabakh Armenian human rights ombudsman, Gegham Stepanyan, reported several children have been injured in the attacks.

Concern is growing over the fate of the civilians effectively trapped in the crossfire, as well as the risk of yet another full-blown war in the former Soviet Union.

During the Soviet era, Nagorno-Karabakh was an autonomous region inside the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic, home to both ethnic Armenians and Azerbaijanis, but the absence of internal borders made its status largely unimportant. That all changed when Moscow lost control of its peripheral republics, and Nagorno-Karabakh was formally left inside Azerbaijan’s internationally recognized territory.

Amid the collapse of the USSR from 1988 to 1994, Armenian and Azerbaijani forces fought a grueling series of battles over the region, with the Armenians taking control of swathes of land and forcing the mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Azerbaijanis, razing several cities to the ground. Since then, citing a 1991 referendum — boycotted by Azerbaijanis — the Karabakh-Armenians have unilaterally declared independence and maintained a de facto independent state.

For nearly three decades that situation remained stable, with the two sides locked in a stalemate that was maintained by a line of bunkers, landmines and anti-tank defenses, frequently given as an example of one of the world’s few “frozen conflicts.”

However, that all changed in 2020, when Azerbaijan launched a 44-day war to regain territory, conquering hundreds of square kilometers around all sides of Nagorno-Karabakh. That left the ethnic Armenian exclave connected to Armenia proper by a single road, the Lachin Corridor — supposedly under the protection of Russian peacekeepers as part of a Moscow-brokered ceasefire agreement.

With Russia’s ability to maintain the status quo rapidly dwindling in the face of its increasingly catastrophic war in Ukraine, Azerbaijan has moved to take control of all access to the region. In December, as part of a dispute supposedly over illegal gold mining, self-declared “eco-activists” — operating with the support of the country’s authoritarian government — staged a sit-in on the road, stopping civilian traffic and forcing the local population to rely on Russian peacekeepers and the Red Cross for supplies.

That situation has worsened in the past two months, with an Azerbaijani checkpoint newly erected on the Lachin Corridor refusing to allow the passage of any humanitarian aid, save for the occasional one-off delivery. In August, amid warnings of empty shelves, malnourishment and a worsening humanitarian crisis, Luis Moreno Ocampo, the former chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, published a report calling the situation “an ongoing genocide.”

Azerbaijan denies it is blockading Nagorno-Karabakh, with Hajiyev telling POLITICO the country was prepared to reopen the Lachin Corridor if the Karabakh-Armenians accepted transport routes from inside Azerbaijani-held territory. Aliyev has repeatedly called on Armenian forces in Nagorno-Karabakh to stand down, local politicians to resign and those living there to accept being ruled as part of Azerbaijan.

Over the past few months, the U.S., EU and Russia have urged Azerbaijan to keep faith during diplomatic talks designed to end the conflict once and for all, rather than seeking a military solution to assert control over the entire region.

As part of the talks in Washington, Brussels and Moscow, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan made a series of unprecedented concessions, going as far as recognizing Nagorno-Karabakh as Azerbaijani territory. However, his government maintains it cannot sign a peace deal that does not include internationally guaranteed rights and securities for the Karabakh-Armenians.

Aliyev has rejected any such arrangement outright, insisting there should be no foreign presence on Azerbaijan’s sovereign territory. He insists that as citizens of Azerbaijan, those living there will have the same rights as any other citizen — but has continued fierce anti-Armenian rhetoric including describing the separatists as “dogs,” while the government issued a postage stamp following the 2020 war featuring a worker in a hazmat suit “decontaminating” Nagorno-Karabakh.

Unwilling to accept the compromise, Azerbaijan has accused Armenia of stalling the peace process. According to former Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Elmar Mammadyarov, a military escalation is needed to force an agreement. “It can be a short-term clash, or it can be a war,” he added.

Facing growing domestic pressure amid dwindling supplies, former Karabakh-Armenian President Arayik Harutyunyan stood down and called elections, lambasted as a provocation by Azerbaijan and condemned by the EU, Ukraine and others.

Azerbaijan also alleged Armenian saboteurs were behind landmine blasts it says killed six military personnel in the region, while presenting no evidence to support the claim.

Armenia is formally an ally of Russia, and a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) military bloc. However, Russian peacekeepers deployed to Nagorno-Karabakh have proven entirely unwilling or unable to keep Azerbaijani advances in check, while Moscow declined to offer Pashinyan the support he demanded after strategic high ground inside Armenia’s borders were captured in an Azerbaijani offensive last September.

Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko previously said Azerbaijan has better relations with the CSTO than Armenia, despite not being a member, and described Aliyev as “our guy.”

Since then, Armenia — the most democratic country in the region — has sought to distance itself from the Kremlin, inviting in an EU civilian observer mission to the border. That strategy has picked up pace in recent days, with Pashinyan telling POLITICO in an interview that the country can no longer rely on Russia for its security. Instead, the South Caucasus nation has dispatched humanitarian aid to Ukraine and Pashinyan’s wife visited Kyiv to show her support, while hosting U.S. troops for exercises.

Moscow, which has a close economic and political relationship with Azerbaijan, reacted furiously, summoning the Armenian ambassador.

In a message posted on Telegram on Tuesday, Dmitry Medvedev, former president of Russia and secretary of its security council, said Pashinyan “decided to blame Russia for his botched defeat. He gave up part of his country’s territory. He decided to flirt with NATO, and his wife took biscuits to our enemies. Guess what fate awaits him…”

The South Caucasus is a tangled web of shifting alliances.

Russia aside, Armenia has built close relations with neighboring Iran, which has vowed to protect it, as well as India and France. French President Emmanuel Macron has previously joined negotiations in support of Pashinyan and the country is home to a large and historic Armenian diaspora.

Azerbaijan, meanwhile, operates on a “one nation, two states” basis with Turkey, with which it has deep cultural, linguistic and historical ties. It also receives large shipments of weaponry and military hardware from Israel, while providing the Middle Eastern nation with gas.

The EU has turned to Azerbaijan to help replace Russia as a provider of energy. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen made an official visit to the capital, Baku, last summer in a bid to secure increased exports of natural gas, describing the country as a “reliable, trustworthy partner.”

Gabriel Gavin

Source link

VIENNA — No one does victimhood quite like Austria.

Over the past century, the Central European country has presented itself to the outside world as an innocent bystander on an island of gemütlichkeit, doing what it can to get by in a treacherous global environment.

“Austria was always apolitical,” insists Herr Karl, the archetypal Austrian opportunist, brought to life in 1961 by Helmut Qualtinger, the country’s greatest satirist. “We were never political people.”

Recalling Austria’s collaboration with the Nazis, Herr Karl, a portly stockist who speaks in a working-class Viennese dialect, was full of self pity: “We scraped a bit of cash together — we had to make a living…How we struggled to survive!”

Russia’s war on Ukraine offers a bitter reminder that Austria remains a country of Herr Karls, playing all sides, professing devotion to Western ideals, even as they quietly look for ways to continue to profit from the country’s friendly relations with Moscow.

The most glaring example of this hypocrisy is Austria’s continued reliance on Russian natural gas, which accounts for about 55 percent of the country’s overall consumption. Though that’s down from 80 percent at the beginning of 2022, Austria, in contrast to most other EU countries, remains dependent on Russia.

Confront an Austrian government official with this fact and you’ll be met with a lengthy whinge over how the country, one of the world’s richest, is struggling to cope with the economic crosswinds triggered by the war. That will be followed by a litany of examples of how a host of other EU countries is guilty of much more egregious behavior vis a vis Moscow.

The unspoken, if inevitable, conclusion: the real victim here is Austria.

The myth of Austrian victimhood has long been a leitmotif of the country’s bilious tabloids, which serve readers regular helpings of all the ways in which the outside world, especially Brussels and Washington, undermines them.

Earlier this month, the EU’s representative in Austria, Martin Selmayr, ended up in the sights of the tabloids — and the government — for uttering the inconvenient truth that the millions Vienna pays to Russia for gas every month amounted to “blood money.”

“He’s acting like a colonial army officer,” fumed Andreas Mölzer, a right-wing commentator for the Kronen Zeitung, Austria’s best-selling tabloid, noting with delight that both of Selmayr’s grandfathers were German generals in the war.

“The Eurocrats have this attitude that they can just tell Austrians what to do,” Mölzer concluded.

Yet if Austria’s history since the collapse of the Habsburg empire in 1918 has shown anything, it’s that the country needs outside supervision. Left to their own devices, Austrians’ worst instincts take hold.

One needn’t look further than 1938 to understand the implications. But there’s no shortage of other examples: voters’ enthusiastic support for former United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim as president in 1986, despite credible evidence that he had lied about his wartime service as an intelligence officer for the Nazis; the state’s foot-dragging on paying reparations to slave laborers used by Austrian companies during the war; the resistance to return valuable artworks looted from Jews by the Nazis to their rightful owners.

Not that Austrians learn from their mistakes. To this day, Austrians rarely heed the better angels of their nature unless the outside world forces them to, either by shaming them into submission or brute force.

That said, the West is almost as much to blame for Austria’s moral shortcomings as the Austrians themselves.

The Magna Carta for Austria’s cult of victimhood can be found in the so-called Moscow Declarations of 1943, in which the allied powers declared the country “the first free country to fall a victim to Hitlerite aggression.” Though the text also stresses that Austria bears a responsibility — “which she cannot evade” — for collaborating with the Nazis, the Austrians latched onto the “victim” label after the war and didn’t look back.

In the decades that followed, the country relied on its stunning natural beauty and faded imperial charm to transform its international image into that of an alpine Shangri-La, a snow-globe filled with prancing Lipizzaners and jolly folk enjoying Wiener schnitzel and Sachertorte.

A key element of that gauzy fantasy was the country’s neutrality, imposed on it in 1955 by the Soviet Union as a condition for ending Austria’s postwar allied occupation. At the time, Austrians viewed neutrality as a necessary evil towards regaining full sovereignty.

During the course of the Cold War, however, neutrality took on an almost religious quality. In the popular imagination, it was neutrality, coupled with Austrians’ deft handling of Soviet leaders, that allowed the country to escape the fate of its Warsaw Pact neighbors (while also doing business with the Eastern Bloc).

Today, Austrian neutrality is little more than a convenient excuse to avoid responsibility.

Austria’s center-right-led government insists that on Ukraine it is only neutral in terms of military action, not on political principle. In other words, it won’t send weapons to Kyiv, but it does support the EU’s sanctions and allows arms shipments destined for Ukraine to pass through Austrian territory.

At the same time, many Austrian companies continue to conduct brisk business with Russia for which they face little criticism at home.

In the Austrian population as a whole, decades of fetishizing neutrality has left many convinced that it’s their birthright not to take sides. Most are blissfully unaware of the EU’s mutual defense clause, under which member states agree to come to one another’s aid in the event of “armed aggression.”

That mentality explains why Austria’s political parties — with the notable exception of the liberal Neos — refuse to touch, or even debate, the country’s neutrality and its security implications.

In March, just as Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy began an address via video to Austria’s parliament, Freedom Party MPs placed signs stamped with “Neutrality” and “Peace” on their desks before standing up in unison and leaving the chamber.

The far right wasn’t alone in its disapproval of Zelenskyy. More than half of the Social Democratic MPs also boycotted the event to avoid upsetting Russia.

Andreas Babler, who took over as leader of the Social Democrats in June, has a long history of opposing not just NATO, but Austrian participation in any EU defense initiatives.

In 2020, he characterized the EU as “the most aggressive military alliance that has ever existed,” adding that it “was worse than NATO.”

It’s an extraordinary assertion given that NATO is the only thing that kept the Soviet Union from swallowing Austria during the Cold War. The defense alliance, which Austrian leaders briefly entertained joining in the 1990s, remains the linchpin of the country’s security for a simple reason: Austria’s only non-NATO neighbor is Switzerland.

Austria’s neutrality and geographic good fortune have led it to spend next to nothing on defense. Last year, for example, spending fell to just 0.8 percent of GDP from 0.9 percent, putting it near the bottom of the EU league table with the likes of Luxembourg, Ireland and Malta.

A few years ago, the country’s defense minister even proposed doing away with “national defense” altogether so that the army could concentrate on challenges such as natural disaster relief and combatting cyber threats. The idea was ultimately rejected, but that it was proposed at all — by the person who oversees the military no less — illustrates how seriously Austria takes its security needs.

Over the past year, the government has pledged to increase defense spending, yet those plans are still well below what the country would be obligated to pay were it in NATO.

Put simply, Austria is freeloading on its neighbors and the United States and will continue to do so until it’s pressured to change course.

That’s why it needs more straight talk from people like Selmayr, not less.

A few weeks before his “blood money” remarks, the diplomat told a Vienna newspaper that “the European army is NATO,” noting that the accession of Sweden and Finland to the alliance would leave only Austria and a few small island states outside the tent.

The reality check dashed Austria’s hope that it could avoid paying its share for EU defense by waiting for Brussels to create its own force.

Even so, rhetoric alone is not going to convince Austria to shift course. Nearly 80 percent of Austrians support neutrality because it’s so comfortable. The EU and the U.S. need to make it uncomfortable.

At the moment, most Austrians only see the upsides to neutrality; yet that’s only because the West has refused to impose any costs on the country for freeriding. That needs to change.

Critics of a more aggressive approach towards Vienna argue that it will only harden the population’s resolve to sustain neutrality and bolster the far right. That may be true in the short term, but the history of foreign pressure on Austria, especially from Washington — be it the isolation it faced during the Waldheim affair or the push to compensate slave laborers from the war — shows that the interventions ultimately work.

If forced to choose between remaining in the Western fold or facing isolation, Austrians will always chose the former.

Though almost no Austrian security officials will say so publicly, few have any illusions about the necessity of a sea change. More than one-third acknowledge that the country’s neutrality is no longer credible, according to a study published this month by the Austrian Institute for European and Security Policy. A further third say the country’s participation in the EU’s common foreign and security policy has a “strong influence” on the credibility of its neutrality claim (presumably not in a good way).

And nearly 60 percent say the country needs to improve its interoperability with NATO in order to fight alongside its EU allies in the event of an armed conflict.

The problem is that no one is forcing them.

If Austria’s partners continue to avoid a confrontation, the country is likely to continue its slide towards Orbánism.

The Freedom Party, which wants to suspend EU aid for Ukraine and lift sanctions against Russia, leads the polls by a widening margin with just a year until the next national election. With neighboring Slovakia on a similar trajectory, Russian President Vladimir Putin may soon have a major foothold in the heart of the EU.

So far, the EU and Washington have been silent on the Freedom Party’s worrying rise, counting on Austrians to snap out of it.

Barring foreign pressure, they won’t. Why would they? With its populist prescriptions and beer hall rhetoric, the Freedom Party encourages Austrians to see themselves as what they most want to be: victims.

Or as Herr Karl famously put it: “Nothing that they accused us of was true.”

Matthew Karnitschnig

Source link

Chinese travelers are returning to Banyan Tree Holdings hotels, it’s founder told CNBC.

Christian Heeb| Prisma By Dukas | Universal Images Group | Getty Images

A dearth of Chinese travelers is nothing to “worry about,” said Banyan Tree Holdings founder Ho Kwon Ping.

“They are definitely going to come back,” he told CNBC’s Chery Kang at the Milken Institute’s Asia Summit on Wednesday.

“China is just a temporary blip,” he said. “Most of us in the hospitality industry, a year or so ago, predicted that Chinese tourism would only start to rebound around maybe this year or even next year.”

No one expected a quick turn-around from lockdown to mass travel, he added.

For Banyan Tree Holdings — which operates more than 60 hotels in 17 countries — Ho said “Chinese tourism [is] coming back quite strongly.”

What’s missing are the “mass group tours, which provide the numbers, but they don’t come to our hotels anyway,” he said.

“So you have a lot more free individual travelers … and they’re the ones who can pay the higher airfares and so on.”

He’s also bullish on the tourism market within China.

“The Chinese government made it very clear, they don’t want to have a heavy investment-led growth, they want consumption-based growth and consumption equals tourism. And tourism, as any economist will tell you, has got the greatest sort of trickle-on effect,” he said.

Ho also dismissed concerns about the turmoil surrounding China’s real estate market, which makes up about 30% of its economy.

“The banking system is not going to collapse because it’s Chinese banks that are lending money,” he said.

We’re comfortable with a China real estate story, because we had a number of hotels in China which were all sold prior to the property bubble.

Ho Kwon Ping

Banyan Tree Holdings

“So that’s why you see things like Country Garden … near to going bust, yet not going bust,” he said, referring to the Chinese property giant that narrowly missed a default.

In addition, “the percentage of the Chinese population that actually still lives in modern housing is not halfway near what it is in the Western world. So there’s a lot of demand still.”

As to his company’s exposure to a Chinese real estate bubble, he said: “We’re comfortable with a China real estate story, because we had a number of hotels in China which were all sold prior to the property bubble.”

Ho said he believed Singapore, where his hospitality brand is headquartered, can help soothe geopolitical tensions that have escalated between China and the United States.

“I think Singapore can actually play a very important role in trying to make the U.S., the West in particular, understand that the rise of China is the rise of an entire civilization — and that it’s not a zero-sum game where they’re trying to rise to the extent of putting America and the West down.”

The Western psyche has been too absorbed by the Cold War, which was a zero-sum game, he said.

Even though the West has been dominant for the last 300 years, one global dominant power is not sustainable into perpetuity, he said.

“I think we’re going back to what I call ‘Back to the future’ — like in the movie, where the world 50 years from now will consist of various great civilizations,” he said.

“I use the word civilization because it’s not about economics. It’s not about military power, even politics [or] the idea of the only criteria by which you should judge a country’s politics is whether it practices liberal democracy … I think that’s all changing.”

Nuclear power has been touted as a proven, safe way of producing clean energy, but why isn’t it more widely adopted?

Sean Gallup | Getty Images News | Getty Images

As the world pushes toward its goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, nuclear power has been touted as the way to bridge the energy gap — but some, like Greenpeace, have expressed skepticism, warning that it has “no place in a safe, clean, sustainable future.”

Nuclear energy is not only clean. It is reliable and overcomes the intermittent nature of renewables like wind, hydro and solar power.

“How do you provide cheap, reliable and pollution-free energy for a world of 8 billion people? Nuclear energy is really the only scalable version of that, renewables are not reliable,” Michael Shellenberger, founder of environmental organization Environmental Progress, told CNBC.

Governments have started to pour money into the sector after years of “treading water,” according to a report by Schroders on Aug. 8.

According to the report, there are 486 nuclear reactors either planned, proposed or under construction as of July, amounting to 65.9 billion watts of electric capacity – the highest amount of electric capacity under construction the industry has seen since 2015.

Only a few years ago, the International Energy Agency had warned that nuclear power was “at risk of future decline.” The report in 2019 said then that “nuclear power has begun to fade, with plants closing and little new investment made, just when the world requires more low-carbon electricity.”

Schroders noted that nuclear power is not only scalable, but much cleaner — emitting just 10-15 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt hour. That’s competitive with both wind and solar energy and substantially better than coal and natural gas.

Nuclear power is also the second largest source of low carbon energy after hydro power, more than wind and solar combined, Schroders said.

Shellenberger’s view is that renewable energy is reaching the limits of what it can achieve in many countries. For example, hydroelectric power is not viable in all countries, and those that have them are “tapped out,” which means they cannot exploit any more land or water resources for that purpose.

Nuclear power is a great alternative, with “very small amounts of waste, easy to manage, never hurt anybody, very low cost when you build the same kind of plants over and over again,” he added.

That’s the reason why nations are having a second look at nuclear power, Shellenberger said. “It’s because renewables aren’t able to take us where we need to go. And countries want to be free of fossil fuels.”

Twelve years after Fukushima, we’re just getting better at operating these plants. They’re more efficient, they’re safer, we have better training.

Michael Shellenberger

Environmental Progress

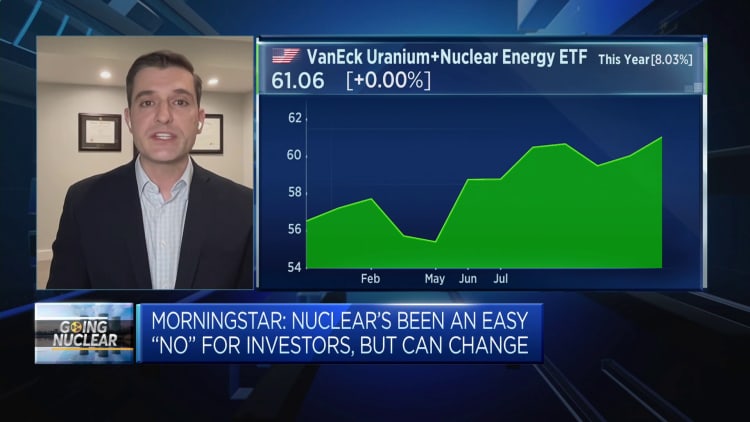

In an interview with CNBC’s “Street Signs Asia” last week, Adam Fleck, director of research, ratings and ESG at Morningstar, said the social concern around nuclear power is “somewhat misunderstood.”

While the tragedies in Chernobyl and Fukushima cannot be forgotten, using nuclear is one of the safest ways to produce energy, even taking into consideration the need to store the nuclear waste.

“Many of those [storage facilities] are highly protected. They’re protected against earthquakes, tornadoes, you name it. But there’s a reason why there hasn’t been a significant tragedy or concern related to storage of nuclear waste.”

Shellenberger said: “Twelve years after Fukushima, we’re just getting better at operating these plants. They’re more efficient, they’re safer, we have better training.”

There have been new designs for nuclear power plants that have also enhanced safety, “but really what’s made nuclear safe has been the kind of the boring stuff, the stuff of the trainings and the routines and the best practices,” he told CNBC.

So, if nuclear has been a tested, proven and safe way of generating power, why isn’t it more widely adopted?

Fleck said it boils down to one main factor: cost.

The extra time that nuclear plants take to build has major implications for climate goals, as existing fossil-fueled plants continue to emit carbon dioxide while awaiting substitution.

“I think the biggest issue of nuclear has actually been cost economics. It’s very costly to build a nuclear plant up front. There’s a lot of overruns, a lot of delays. And I think, for investors looking to put money to work in this space, they need to find players that have a strong track record of being able to build out that capacity.”

But not everyone is convinced.

A report by global campaigning network Greenpeace in March 2022 was of the position that besides the commonly held concern of nuclear safety, nuclear energy is too expensive and too slow to deploy compared to other renewables.

Greenpeace noted that a nuclear power plant takes about 10 years to build, adding “the extra time that nuclear plants take to build has major implications for climate goals, as existing fossil-fueled plants continue to emit carbon dioxide while awaiting substitution.”

Furthermore, it points out that uranium extraction, transport and processing are not free of greenhouse gas emissions either.

Greenpeace acknowledged that “all in all, nuclear power stations score comparable with wind and solar energy.” However, wind and solar can be implemented much faster and on a much bigger scale, making a faster impact on carbon emissions and the clean energy transition.

Nuclear power is a “distraction” from the “answer we need” — such as renewables and energy storage solutions to mitigate the unreliability from renewables, said Dave Sweeney, a nuclear analyst and nuclear-free campaigner with the Australian Conservation Foundation.

“That’s the way that we need to go, to keep the lights on and the Geiger counters down,” he told CNBC’s “Street Signs Asia” on Friday.

Press play to listen to this article

Voiced by artificial intelligence.

KYIV — Ukraine’s long-range Beaver drones seem to be making successful kamikaze strikes in the heart of Moscow, but Serhiy Prytula is coy about how much he knows.

“We are not sure whether we are involved in this,” he says with a charming but inscrutable smile, when asked about these mysterious new weapons.

Prytula rose to fame — just like President Volodymyr Zelenskyy — as an actor, TV star and comedian, but is now best known for his contribution to the war, running a foundation that acquires components, helps support domestic arms production and supplies front-line forces. Tracking down parts for drones has proved to be one of his fortes.

Whether or not Prytula played any role in finding parts for the Beaver, it has now joined the ranks of other homegrown creations such as the Shark, Leleka and Valkyrie.

From the outside, his foundation looks like any other nondescript five-story apartment block in the quiet side streets of Kyiv. Inside, it is a chaotic human hive of volunteers, preparing packages and dispatching deliveries to soldiers on the front. On August 9, the team packed 75 drones for military units. That’s barely a drop in the ocean, given the needs of Ukraine’s forces across a 1,000-kilometer front, but every extra eye in the sky can help save dozens of lives.

The crowd of young, energetic volunteers at Prytula’s headquarters epitomizes an important dimension of the war: Ukrainians are increasingly taking matters into their own hands when it comes to weapons supply. With the defense ministry and the traditional state arms sector widely criticized for inefficiency and tarnished by corruption scandals over past years, the country is now witnessing an explosion of private enterprise to deliver kit to the front lines and to ramp up domestic production in the most hazardous of conditions. With arms-makers being prime targets for Russian cruise missiles, factories are spreading their manufacturing over numerous secret locations.

This sense that Ukrainians need to take the initiative at home both by scouring the global arms bazaar for hi-tech gizmos and by making more of their own heavy armor and shells is only amplified by the looming threat of a return to the White House by Donald Trump, who argues that America should not be “sending very much” to Ukraine and that Kyiv should sue for peace with the invader. Other Republican candidates have only heightened Ukrainians’ fears that the next U.S. president could sell out their young democracy to the Kremlin.

In addition to the aerial drones, there have been other homegrown success stories — Ukrainian-made armored vehicles are on the front lines beside U.S. Bradleys and locally made maritime drones have hit Russian ships in the Black Sea.

Not that anyone reckons going it alone is an option. Ukraine cannot even begin to match the vast military expenditure of Russia — Kyiv is expected to spend €24 billion on defense over 2023, while Russia is probably splurging well over €80 billion — so foreign assistance will always prove vital to keeping Ukraine in the fight.

But that’s no reason to sit idly by. Almost an entire country has mobilized for national defense, and there are many ways in which entrepreneurial private suppliers are now proving nimbler than state behemoths and bureaucrats in getting soldiers what they need.