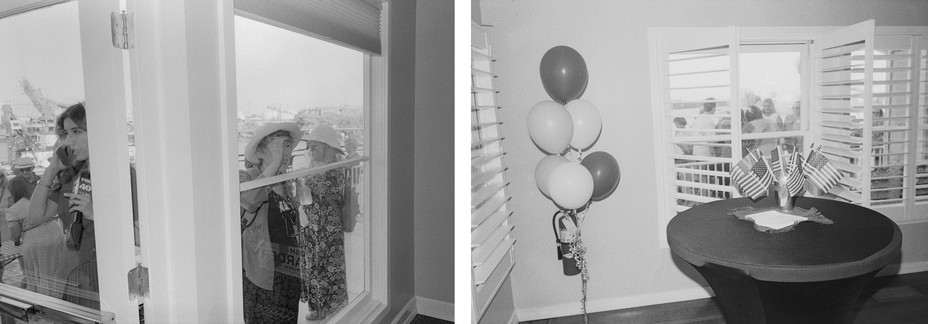

Representative Adam Schiff was mingling his way through a friendly crowd at a Democratic barbecue when the hecklers arrived—by boat. Schiff and two other Senate candidates, Representatives Katie Porter and Barbara Lee, convened on the back patio of a country club overlooking the port of Stockton, California. Schiff spoke first. “It’s such a beautiful evening,” he said, thanking the host, local Democratic Representative Josh Harder.

It was hard to know what to make of the protest vessel, except that its seven passengers were yelling things as Schiff began his remarks. And not nice things. Although their words were tough to decipher, the flag flying over the craft made clear where they were coming from: FUCK BIDEN. Notably, of the three candidates, Schiff was the only one I heard singled out by name—or, in one case, by a Donald Trump–inspired epithet (“Shifty”) and, in another, a four-letter profanity similar to the congressman’s surname (clever!).

Schiff is used to such derision and says it proves his bona fides as a worthy Trump adversary. Given the laws of political physics today, it also bodes well for his Senate campaign. The principle is simple: to be despised by the opposition can yield explicit benefits. This is especially true when you belong to the dominant party, as Schiff does in heavily Democratic California. One side’s villain is the other side’s champion. Adam Schiff embodies this rule as well as any politician in the country.

In recent years, Schiff has had a knack for eliciting loud and at times unhinged reactions from opponents, even though he himself tends to be quite hinged. The 45th president tweeted about Schiff 328 times, as tallied by Schiff’s office. Tucker Carlson called the congressman “a wild-eyed conspiracy nut.” A group of QAnon followers circulated a report in 2021 that U.S. Special Forces had arrested Schiff and that he was in a holding facility awaiting transfer to Guantánamo Bay for trial (the report proved erroneous). Before Schiff had a chance to meet his new Republican colleague Anna Paulina Luna, of Florida, she filed a resolution condemning his “Russia hoax investigation” and calling for him to potentially be fined $16 million (the resolution failed).

This onslaught has also been good for business, inspiring equal passion in Schiff’s favor. A former prosecutor, he became an icon of the left for his emphatic critiques of Trump’s behavior in office, including as the lead House manager in Trump’s first impeachment trial. “You know you can’t trust this president to do what’s right for this country,” Schiff said as part of his closing argument, a speech that became a rallying cry of the anti-Trump resistance. (“I am in tears,” the actor Debra Messing wrote on Twitter.) Opponents gave grudging respect. “They nailed him,” Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell told Mitt Romney, according to an account in a new Romney biography by my colleague McKay Coppins. Schiff’s own Trump-era memoir, Midnight in Washington, became a No. 1 New York Times best seller.

You could draw parallel lines charting the levels of vilification that Schiff has encountered and his name recognition and fundraising numbers. Both the good and the grisly have boosted Schiff’s media profile, which he has adeptly cultivated. Schiff has come in at or near the top of the polls in the Senate race so far, along with Porter. A Berkeley IGS survey released last week revealed him as the best-known of the candidates vying for the late Dianne Feinstein’s job; 69 percent of likely voters said they could render an opinion of him (40 percent favorable, 29 percent unfavorable). He raised $6.4 million in the most recent reporting period, ending the quarter with $32 million cash on hand, or $20 million more than the runner-up, Porter. That’s more than any Senate candidate in the country this election cycle, and a massive advantage in a state populated by about 22 million registered voters covering some of the nation’s most expensive media markets.

“He’s become an inspiration and a voice of reason for many of us,” Becky Espinoza, of Stockton, told me at the Democratic barbecue.

Or at least the sector of “many of us” who don’t want him dead.

Schiff started getting threats a few months into Trump’s presidency. “Welcome to the club,” Nancy Pelosi, his longtime mentor, told him. He endured anti-Semitic screeds online and actual bullets sent to his office bearing the names of Schiff’s two kids. “I can’t stand the fact that millions of people hate you; they just hate you,” Schiff’s wife, Eve—yes, Adam and Eve—told her husband after the abuse started. “They just hate you.”

No one deserves to be subjected to such menace, and the threats can be particularly chilling for a member of Congress who would not normally have a protective detail. (Schiff’s office declined to discuss its security staffing and protocols.) Schiff is not shy about repeating these ugly stories, however. There’s an element of strategic humblebragging to this, as he is plainly aware that being a target of the MAGA minions can be extremely attractive to the Democratic voters he needs.

In June, congressional Republicans led a party-line vote to censure Schiff for his role in investigating Trump. As then-Speaker Kevin McCarthy attempted to preside, Democrats physically rallied around Schiff on the House floor chanting “shame” at McCarthy. On the day of his censure, Schiff was interviewed on CNN and twice on MSNBC; the next morning he appeared on ABC’s The View. “Whoever it was that introduced that censure resolution against him probably ensured Adam’s victory,” Representative Mike Thompson, another California Democrat, told me. A few colleagues addressed him that day as “Senator Schiff.”

I dropped in on Schiff periodically over the past few months as he traversed the chaos of the Capitol, weighed in on Trump’s legal travails, and campaigned across California. What did a Senate candidacy look like for a Trump-era cause célèbre who is revered and reviled with such vigor? I found it a bit odd to see Schiff out in the political wild—glad-handing, granny-hugging, and, at the barbecue in late August, nearly knocking a plate of brisket from the grip of an eager selfie-seeker. He has graduated to a full-on news-fixture status, someone perpetually framed by a screen or viewed behind a podium, as if he emerged from his mother’s womb and was dropped straight into a formal courtroom, hearing room, or greenroom setting.

I watched a number of guests in Stockton clutch Schiff’s hand and address him in plaintive tones. “After I stopped crying a little bit, I just wanted to thank him for all he did during impeachment and to just save our democracy,” said Espinoza, following her brief meeting with the candidate.

Nearby, David Hartman, of Tracy, California, put down a paper plate of chicken, pickles, and corn salad and made his way to Schiff. “I just want to shake the man’s hand and thank him,” Hartman told me, which is what he did. So did his wife, Tracy (of Tracy!), who was likewise surprised to find herself in tears.

“I’m like a human focus group,” Schiff told me, describing how strangers approach him at airports. “Sometimes I will have two people come up to me simultaneously. One will say, ‘You are Adam Schiff. I just want to shake your hand. You’re a hero.’ And the other will say, ‘You’re not my hero. Why do you lie all the time?’”

For his first eight terms in Congress, Schiff, 63, was not much recognized beyond the confines of the U.S. Capitol or the cluster of affluent Los Angeles–area neighborhoods he has represented in the House since 2001. “I think, before Trump, if you had to pick one of these big lightning rods or partisan bomb-throwers, you would not pick me,” Schiff told me.

Largely true. Schiff speaks in careful, somewhat clipped tones, with a slight remnant of a Boston accent from his childhood in suburban Framingham, Massachusetts. (His father was in the clothing business and moved the family to Arizona and eventually California.) A Stanford- and Harvard-trained attorney, Schiff gained a reputation as an ambitious but low-key legislator in the House, and a deft communicator in service of his generally liberal positions.

After Trump’s election, however, Schiff’s district effectively became CNN, MSNBC, and the network Sunday shows, along with the scoundrel’s gallery of right-wing media that pulverized him hourly. This included a certain Twitter feed. The worst abuse Schiff received started after Trump’s maiden tweet about him dropped on July 24, 2017. This was back in an era of relative innocence, when it was still something of a novelty for a sitting president to attack a member of Congress by name—“Sleazy Adam Schiff,” in this case.

Schiff tweeted back that Trump’s “comments and actions are beneath the dignity of the office.” Schiff would later reveal that he rejected a less restrained rejoinder suggested by Mike Thompson, his California colleague: “Mr. President, when they go low, we go high. Now go fuck yourself.” Anyway, that was six years, two impeachments, four indictments, 91 felony counts, and 327 tweets by Donald Trump about Adam Schiff ago.

“Adam is one of the least polarizing personalities you will ever find,” said another Democratic House colleague, Dan Goldman, of New York. “The reason he’s become such a bogeyman for the Republican Party is simply that he’s so effective.” Goldman served as the lead majority counsel during Trump’s first impeachment, working closely with Schiff. “We originally met in the greenroom of MSNBC in June of 2018,” Goldman told me. (Of course they did.)

Schiff understands that some of the rancor directed at him is performative, and likes to point out the quiet compliments he receives from political foes. Trump used to complain on Twitter that Schiff spent too much time on television—in reality, a source of extreme envy for the then-president. Schiff tells a story about how Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, came to Capitol Hill for a deposition from members of Schiff’s Intelligence committee in 2017. “Kushner comes up to me to make conversation, and to ingratiate himself,” Schiff told me. “And he said, ‘You know, you do a great job on television.’ And I said, ‘Well, apparently your father-in-law doesn’t think so,’ and [Kushner] said, ‘Oh, yes, he does.’” (Kushner didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

One of Trump’s most fervent bootlickers, Senator Lindsey Graham, walked up to Schiff in a Capitol hallway during the first impeachment trial and told him how good of a job he was doing. Schiff, who relayed both this and the Kushner stories in his memoir, says he gets that from other Republicans, too, usually House members he’s worked with—including some who lampoon him in front of microphones. A few House Republicans apologized privately to Schiff, he told me, right after they voted to censure him.

“The apologies are always accompanied by ‘You’re not going to say anything about this, are you?’” Schiff said. When I urged Schiff to name names, to call out the hypocrites, he declined.

I asked Schiff if he would prefer the more anonymous, pre-2017 version of himself running in this Senate campaign, as opposed to the more embattled, death-threat-getting version, who nonetheless enjoys so many advantages because of all the attention. He paused. “I’d rather the country didn’t have to go through all this with Donald Trump,” he said, skirting a direct answer.

As with many members of Congress seeking a promotion or an exit, Schiff gives off a strong whiff of being done with the place. “The House has become kind of a basket case,” he told me, citing one historic grandiloquence that he was recently privy to—the episode in which Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene called her colleague Lauren Boebert a “little bitch” on the House floor.

“And I remember thinking to myself, There used to be giants who served in this body,” Schiff said. He sighed, as he does.

I met with Schiff at the Capitol in early October, amid the usual swirl of weighty events: Feinstein had died three days earlier; news that Governor Gavin Newsom would appoint the Democratic activist Laphonza Butler as her replacement came the night before. That afternoon, Republican Representative Matt Gaetz had filed his fateful “motion to vacate” that would result in the demise of McCarthy’s speakership the next day. Schiff stood just off the House floor, colleagues passing in both directions, Republicans looking especially angry, and reporters gathering around Schiff in a small scrum.

No matter what happens next November, Schiff is not running for reelection in the House. He told me he has long believed that he’d be a better fit for the Senate anyway, where he has been coveting a seat for years. Schiff said he considered running in 2016, after the retirement of the incumbent Barbara Boxer (who was eventually succeeded by Kamala Harris).

A Democrat will almost certainly win the 2024 California race. Senate contests in the state follow a two-tiered system in which candidates from both parties compete in a March primary, and then the two top finishers face off in November, regardless of their affiliation. In addition to Schiff, Porter, and Lee, the former baseball star Steve Garvey, known also for his various divorce and paternity scandals, recently entered the race as a Republican. A smattering of long shots are also running, including the requisite former L.A. news anchor and requisite former Silicon Valley executive. Butler announced on October 19 that she would not seek the permanent job.

To varying degrees, all of the three leading Democratic candidates have national profiles. Lee, who has represented her Oakland-area district for nearly 25 years, previously chaired both the Congressional Progressive and Black Caucuses. Porter was elected to Congress in 2018 and has gained a quasi-cult following as a progressive gadfly who has a knack for conducting pointed interrogations of executives and public officials that go rapidly viral. A few of her fans were so excited to meet Porter at the Stockton barbecue that three actually spilled drinks on her—this according to the congresswoman, speaking at an event a few days later.

Schiff, Porter, and Lee all identify as progressive Democrats on most issues, though Schiff tends to be more hawkish on national security. He voted to authorize the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and supported the 2011 U.S. missile strikes against Libya. Lee, who opposed all three, recently criticized Schiff’s foreign-policy views as “part of the status quo thinking” in Washington. (Porter was not in office then.) Schiff expressed “unequivocal support for the security and the right of Israel to defend itself” after last month’s attacks by Hamas. Lee has been more critical of the Israeli government, and called for a cease-fire immediately after the Hamas attacks. As for Porter, she has been a rare progressive to focus her response on America’s Iran policy, which she called lacking and partly to blame for the attacks.

Although Schiff is best known for his work as a Trump antagonist—and happily dines out on that—he is also wary of letting the former president define him entirely. “This is bigger than Trump,” he reminds people whenever the conversation veers too far in Trump’s inevitable direction. Schiff dutifully pivots to more standard campaign themes, namely the “two hugely disruptive forces” he says have shaped American life: “the changes in our economy” and “the changes in how we get our information.” He reels off the number of cities in California that he’s visited, events he’s done, and endorsements he’s received as proof that he is a workmanlike candidate, not just a citizen of the greenroom.

Recently, he lamented that many of his Republican colleagues are now driven by a “perverse celebrity” that he believes the likes of Greene and Boebert have acquired through their Trump-style antics and ties to the former president. I pointed out to Schiff that he, too, has received a lot of Trump-driven recognition. Doesn’t being affiliated with Trump, whether as an ally or an adversary, have benefits for both sides?

“Well, I don’t view it that way at all,” Schiff said. “I don’t view it as having any kind of equivalence. On one hand, we’re trying to defend our democracy. And on the other hand, we have these aiders and abettors of Trump by these vile performance artists. It’s quite different.”

Schiff’s biggest supporter has been Pelosi, who endorsed him over two other members of her own caucus and delegation. This included Lee, whom Pelosi described to me as “like a political sister.” I spoke by phone recently with the former speaker, who was effusive about Schiff and scoffed at any suggestion that he benefited from his resistance to Trump and the counter-backlash that ensued. “If what’s-his-name never existed, Adam Schiff would still be the right person for California,” Pelosi said. It was one of two occasions in our interview in which she refused to utter the word “Trump.”

“I just don’t want to say his name,” she explained. “Because I worry that he’s going to corrode my phone or something.”

In one of my conversations with Schiff, I asked him this multiple-choice question: Who had raised the most money for him—Adam Schiff, Nancy Pelosi, or Donald Trump? My goal was to get Schiff to acknowledge that, without Trump, he would be nowhere near as well known, well financed, or well positioned to potentially represent the country’s most populous state in the Senate.

“I’m not sure how to answer that,” he said. After a pause, he picked himself. “I am my own biggest fundraiser,” he declared. Okay, I said, but wasn’t Trump the single biggest motivator for anyone to donate?

“It’s the whole package,” Schiff maintained, ceding nothing. He then made sure to mention the person who’s been “most formative in helping shape my career and phenomenally helpful in my campaign—Nancy Pelosi.” He was in no rush to give what’s-his-name any credit.

Mark Leibovich

Source link