This is an opinion editorial by Kudzai Kutukwa, a financial inclusion advocate who was recognized by Fast Company magazine as one of South Africa’s top-20 young entrepreneurs under 30.

“Every record has been destroyed or falsified, every book rewritten, every picture has been repainted, every statue and street building has been renamed, and every date has been altered. And the process is continuing day by day and minute by minute. History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right.”

–George Orwell, “1984”

At the outbreak of the first world war, Great Britain had the world’s most sophisticated undersea telegraph cable system, which wrapped around the entire world. On August 5, 1914, a day after the British had declared war on the Germans, a British ship, the Alert, set sail from the port of Dover with a mission of cutting off all of Germany’s communications with the world by sabotaging the Germans’ undersea cables and the mission was accomplished successfully.

A day before the Alert set sail, on August 4, a man was deployed to the cable station at Porthcurno in Cornwall and the cables carrying traffic across the Atlantic came ashore on the beach. The job title of this man was “censor” and numerous other censors were deployed across the empire, from Hong Kong to Malta to Singapore. Once the censors were in position, a worldwide system of intercepting communications known as “censorship” was born. Its main aim was to prevent the communication of strategic intelligence between the enemy and their agents. In other words, the goal had evolved from just crippling the Germans’ ability to communicate, to also gathering intelligence.

Over 50,000 messages per day were handled by the network of 180 censors at U.K. offices. By leveraging their dominance over the international telegraph infrastructure, the British created the first global communications surveillance system that stretched from Cape Town to Cairo and from Gibraltar to Zanzibar. This became one of the choke points that led to the defeat of the Germans.

While the phenomenon of censorship is by no means a new one, as highlighted by the historical account above, the fact still stands that it’s a weapon that has been deployed throughout history to silence opposing views, cripple independent thought and ultimately subjugate “enemies of the state” or entire nations.

2022 was in many ways what I would personally call the year of the “censor.” As I look back and reflect on 2022, it seems to me that incidents of censorship are now the rule and not the exception thanks to the rise of cancel culture on social media and various independent media voices offering diverse views on controversial topics that, in some cases, contradict the “official narrative.” Honest and open debate is stifled when these views get censored, resulting in further polarization.

Furthermore the convergence of digital platforms and banking has led to the rise of another, more dangerous and pervasive form of censorship: financial censorship. This is a more malicious form of censorship that isn’t just about hindering or intercepting communications, but is characterized by cutting off one’s access to basic financial services, restricting who one can trade with and hindering the ability to transact freely. This includes but isn’t limited to shutting down the bank accounts of political opponents, being blacklisted and deplatformed by payment processors and economic sanctions. What started out as a tool to stop criminals and other bad actors from financing their nefarious activities has now morphed into a weapon for silencing critics, oppressing dissenters and harassing whistleblowers, as well as indirectly controlling the spending habits of people.

Given Bitcoin’s censorship resistance, it too was also subjected to numerous attacks in this past year as the censors clearly understand that it’s an alternative monetary system that they cannot stop, control or influence.

In a world where the definitions of what constitutes “acceptable speech or appropriate behavior” are constantly moving targets, who knows when you may end up having your bank accounts frozen for having a different perspective or for something you posted on social media ten years ago? Will independent thought result in financial retaliation? In this essay I will highlight a few of the key incidents of financial censorship that occurred in 2022 which were basically free Bitcoin marketing campaigns, and more importantly, discuss how Bitcoin is the perfect shield going forward.

The Freedom Convoy

“The greatest danger to the State is independent intellectual criticism.”

–Murray N. Rothbard

The increased levels of collusion between the State, bankers and big tech against individuals and organizations that hold legal but dissenting views is perhaps the most obfuscated and dangerous form of financial censorship.

The Freedom Convoy protests that kicked off on January 22 by Canadian truckers who were protesting against COVID-19 vaccine mandates clearly demonstrated how third-party payment platforms and banks can collude with the State to financially cut off individuals without due process. Through the crowdfunding site GoFundMe the truckers managed to raise approximately $7.9 million in donations. GoFundMe then withheld and later refunded the donations to the donors citing a violation of their terms of service against the promotion of violence.

Not long after that, Prime Minister Trudeau invoked the Emergencies Act, which allowed the government to freeze the bank accounts, suspend insurance policies and withhold other financial services from the protestors and their donors.

During a press conference on the February 14, after the invocation of the Emergencies Act, Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland made the following remarks:

“The government is issuing an order with immediate effect, under the Emergencies Act, authorizing Canadian financial institutions to temporarily cease providing financial services where the institution suspects that an account is being used to further the illegal blockades and occupations. This order covers both personal and corporate accounts…As of today, a bank or other financial service provider will be able to immediately freeze or suspend an account without a court order. In doing so, they will be protected against civil liability for actions taken in good faith. Federal government institutions will have a new broad authority to share relevant information with banks and other financial service providers to ensure that we can all work together to put a stop to the funding of these illegal blockades.”

The Canadian government chose to shut down the protests by nuking the protestors’ financial infrastructure. Financial services providers were given the green light to do so without due process and were given legal cover by the state for any blowback that could result from enforcing this decree. Furthermore, the government intends to extend these measures and make them permanent.

Whether one agrees with the truckers or not, it is very obvious that using financial censorship to resolve domestic dissent is a terrible precedent to set.

On the flip side the weaknesses of State-controlled money were exposed in full view for all to see. This incident was the best Bitcoin commercial ever made, as it simultaneously showed the weaknesses of centralized financial platforms while proving the utility of a decentralized currency like bitcoin.

At the stroke of a pen, thousands of people were denied access to their own money and it was all “perfectly legal.” The message was clear; reliance on a centralized financial system that is biased is very risky. By applying pressure on this one choke point, the expression of other freedoms is also curtailed, whether it’s freedom of expression or freedom of movement as they all contingent on one’s ability to transact. One of the truckers described how his personal and business accounts were shut down. The business in question wasn’t connected in any way with trucking, politics, protests or the Freedom Convoy, but its bank account was still shut down by the Canadian government and this has completely crippled the owner’s ability to make a living.

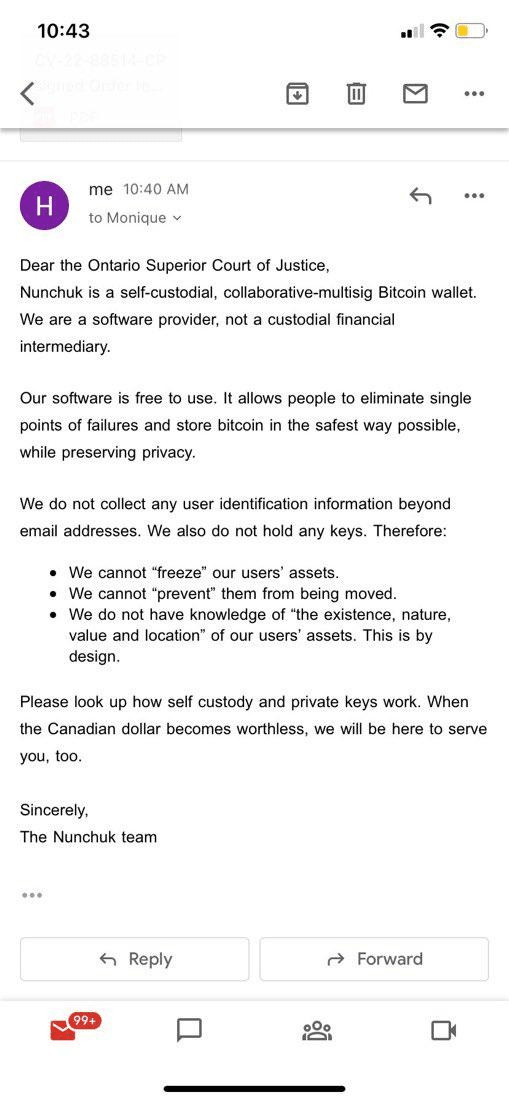

Following the action taken by GoFundMe, a Bitcoin fundraising campaign dubbed “Honk Honk Hodl” was started on Twitter with the intention of raising 21 bitcoin (worth approximately $1,100,000 at the time) for the truckers and they successfully raised more than 14 bitcoin. In response to this, the government extended the ban to include bitcoin and other cryptocurrency donations and pressured cryptocurrency exchanges to freeze the accounts of anyone involved in funding the truckers as well as to share their personal information with the State. The Ontario Superior Court of Justice ordered self-custody wallet provider Nunchuk to disclose user information and freeze Bitcoin wallets of its users in accordance with the government decree. The official response from Nunchuk was as follows:

Once again, Bitcoin’s censorship resistance passed the test, and Nunchuk’s response not only highlights the importance of owning money that cannot be seized or censored, but of self custody as well.

Not to be outdone, the Iranian regime took a page out of the Canadian government’s playbook of using financial censorship as a weapon to crush dissent amongst its citizens when they issued a decree that will enable the state to freeze the bank accounts of women that will not wear a hijab. Protests have been going on in Iran since September 17, when Mahsa Amini, an Iranian woman, was arrested by the morality police for not wearing a hijab and later died under dubious circumstances at a Tehran hospital. The case for Bitcoin, a censorship resistant form of money, has never been stronger.

It’s against this background that I am convinced that central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are a threat to individual liberty and financial sovereignty as they endow the state with the ability to financially censor anyone, for any reason at the push of a button, without due process. In a CBDC world, a protest such as the Freedom Convoy would probably not have happened. This is why it’s a matter of great concern that nine out of 10 of the world’s central banks are currently actively working on launching their own CBDCs. Furthermore, according to a report released by the Bank for International Settlements in May this year, “the growth of cryptoassets and stablecoins’ is the main reason that the majority of these central banks are actively pursuing CBDCs.

In other words, the censors’ top priority is to neuter Bitcoin and stablecoins since they neither want to lose their power to print money ad infinitum nor to loosen their grip on the scepter of financial censorship.

This explains why the Nigerian central bank issued an edict on December 6, that capped ATM withdrawals at a maximum of $45 a day and $225 a week in a bid to coerce more people to use the eNaira, the country’s CBDC. After experiencing similar financial censorship to the truckers in 2020 during the anti-police brutality “End Sars” protests, Nigerians are definitely not keen on signing up for CBDC induced digital serfdom. As a result adoption of the eNaira has been dismal to say the least, with only 0.5% of the country’s 217 million citizens having used it since its launch in October 2021. The Nigerian central bank’s draconian measures to promote the eNaira by declaring war on cash will just serve to strengthen Bitcoin’s appeal and adoption is likely going to keep rising. Having said that, I wouldn’t be surprised to see in the coming year more measures of this sort being implemented by central banks as they “promote” their CBDCs.

Censorship-Resistant Design

“When we can secure the most important functionality of a financial network by computer science rather than by the traditional accountants, regulators, investigators, police, and lawyers, we go from a system that is manual, local, and of inconsistent security to one that is automated, global, and much more secure.”

–Nick Szabo

Bitcoin is a global, fully-decentralized, trustless, permissionless, non-sovereign and censorship-resistant form of money. It exists beyond the control of the State or any corporation and functions perfectly without the need for coordination by any centralized third parties. Of the many attributes of Bitcoin, censorship resistance remains one of the most unappreciated yet very important in this age of pervasive surveillance and financial censorship.

Censorship resistance is the ability of a currency to be stored and transacted, unhindered and unencumbered. Censorship-resistant money is immune to confiscation, freezing or interception by any third party. Anyone can access Bitcoin because it’s permissionless and, as it scales, it becomes more decentralized and therefore harder to censor.

Valid transactions that are processed on the Bitcoin network are uncensorable and no third party can block them or blacklist a wallet address. Users are protected from asset seizures by the state or freezing by private corporations — in short, it is neutral money that is governed by rules and not rulers. If WikiLeaks had been receiving donations via Bitcoin from day one, the financial blockade it experienced would have meant nothing.

The Bitcoin architecture is by design built to be censorship resistant as this ensures that no arbitrary changes to its monetary policy or to the protocol itself can be made unilaterally, thus guaranteeing the stability and integrity of the network. Without this attribute in place, what would be the guarantee that the maximum supply cap of 21 million bitcoin will not be increased unilaterally in future?

As Parker Lewis aptly puts it, “Censorship resistance reinforces scarcity and scarcity reinforces censorship resistance.” Bitcoin’s absolute scarcity is the foundation for every financial incentive that makes the Bitcoin network functional and valuable; thus, without censorship resistance built in, the entire system is compromised.

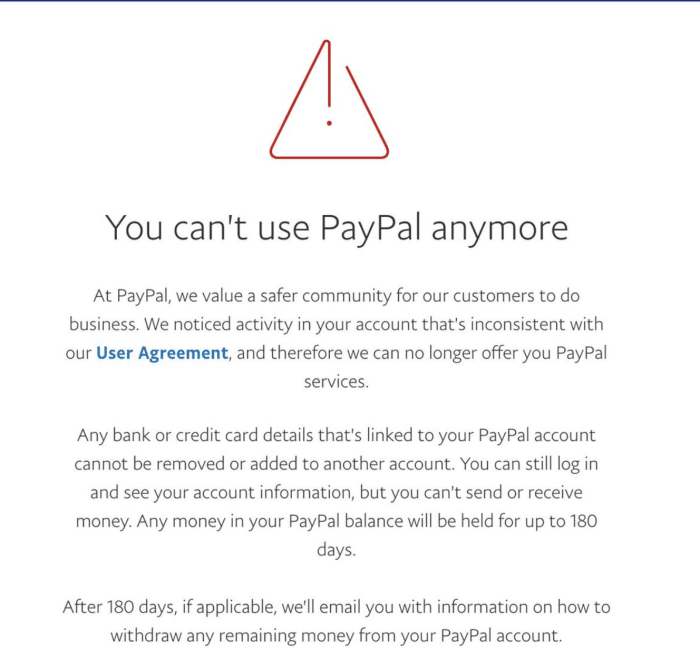

Contrast this with the current fiat system and its various payment rails that have terms of service that can be changed at the drop of a hat by a committee or due to pressure from social justice warriors as well as the State. An example that comes to mind would be PayPal’s deplatforming of alternative media sites, Consortium News and Mint Publishing, for publishing stories that were critical of the “official narrative” with regards to Western support of Ukraine. PayPal didn’t stop there, in September of this year, it also simultaneously shut down the accounts of the Free Speech Union and “UsforThemUK” (a parents group opposed to locking down schools during the pandemic) due to the “nature of its activities.” This was done with no prior warning, or clear explanation and it was unable to withdraw the thousands of pounds’ worth of donations that were still in its account.

Other organizations that were added to PayPal’s blacklist this year include: The Daily Sceptic; the U.K. Medical Freedom Alliance; Law Or Fiction, a website that educates citizens on their rights and how they have been affected by the British government’s response to COVID-19; and Moms For Liberty, to name just a few. These organizations will soon realize that the solution to the predicament of financial censorship is the adoption of a Bitcoin standard, where no entity, no matter how powerful, can censor their transactions.

The Rise Of Financial Restrictions

“Liberty once lost, is lost forever.”

–John Adams

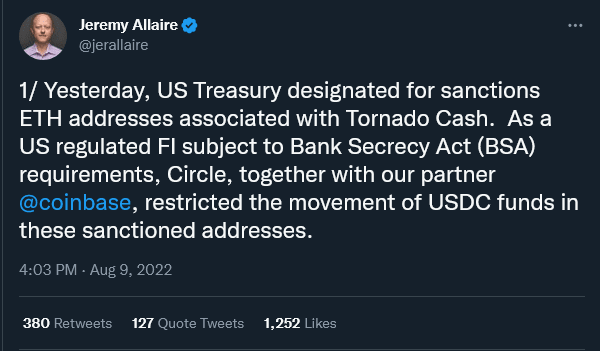

On August 8, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned Tornado Cash (TC), an Ethereum smart contract mixer, and added it to the Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) List. According to OFAC, TC was allegedly used to launder cryptocurrency worth $455 million that was hacked by the North Korean government-backed hacker organization the Lazarus group. According to the Financial Times, a senior, unnamed Treasury official commenting on the sanction of TC said:

“‘We do believe that this action will send a really critical message to the private sector about the risks associated with mixers writ large,’ adding that it was ‘designed to inhibit Tornado Cash or any sort of reconstituted versions of it to continue to operate. Today’s action is the second action by Treasury against a mixer, but it will not be our last.’”

This is clearly a warning that the State intends to continue tightening the screws on financial privacy tools and will not hesitate to blacklist any insufficiently-decentralized protocols. This action by OFAC of sanctioning an open-source protocol sets a precedent that indirectly outlaws financial privacy. This further breeds uncertainty within the open-source community, as developers may be prosecuted for writing code, should it be deployed by criminals later on.

As if on cue, four days after TC was sanctioned, one of TC’s contributing developers, Alex Pertsev, was arrested by Dutch authorities on allegations of money laundering. Apart from being a contributor to TC’s code, no concrete evidence has been disclosed yet that ties Pertsev to the laundered funds, nor have any official charges against him been made, yet he remains in pre-trial detention.

Following a recent hearing, he was remanded in custody until February 20, 2023, pending investigation as the court deemed him to be a flight risk. It remains to be seen how this case will turn out, but as one of the biggest crypto-related cases to reach a court of law, the outcome of it will set a precedent within the EU that could negatively affect the Bitcoin ecosystem in the region, particularly where financial privacy is concerned. This is the slippery slope that we find ourselves on, where the slow creep against financial privacy is another tactic that censors are using to protect their powers.

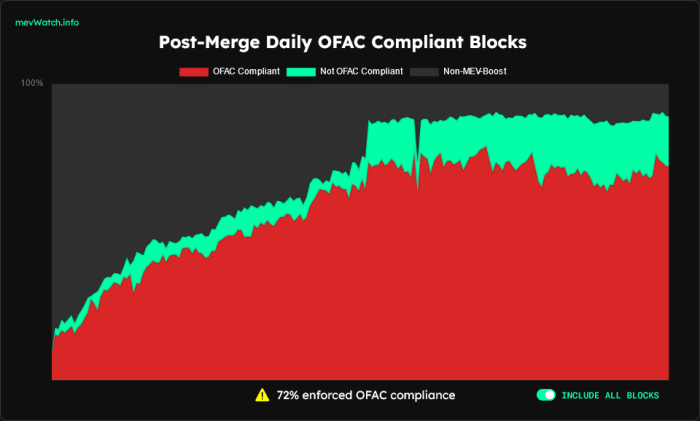

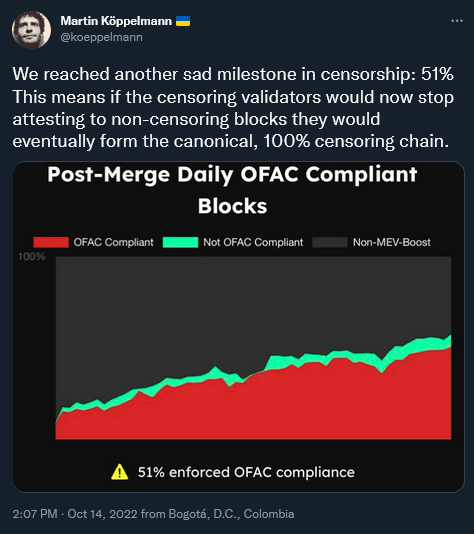

OFAC’s tentacles have also extended to Ethereum, which is gradually getting more centralized and less censorship resistant due to OFAC compliance as MEV-boost relays become more and more dominant. Following the long awaited merge upgrade in September that transitioned Ethereum to a proof-of-stake (PoS) consensus mechanism, data by Santiment indicates that 46.15% of Ethereum’s PoS nodes are controlled by just two addresses that belong to Coinbase and Lido. MEV-boost relays are also centralized entities that function as a bridge between block producers and block builders, giving all Ethereum PoS validators the option to outsource block production to third parties. As a result of this centralization, OFAC-compliant blocks came into existence, where it’s possible to censor certain transactions; like those from blacklisted TC addresses and any other sanctioned wallet addresses as designated by OFAC.

To put things in perspective, as of December 19, 2022, the production of OFAC-compliant blocks on a daily basis stands at 72%, up from 51% in October. While the possibility exists for sanctioned transactions to make it onto the Ethereum blockchain as things currently stand, this will become a rarity as more validators (and relays) will likely opt to exclude those transactions.

In case you weren’t paying attention, this is one of the biggest reasons why calls for Bitcoin to “change the code” and transition to PoS keep getting louder. The censors know that Bitcoin as it exists today is censorship resistant, largely due to proof of work, and in a bid to seize control of it at a protocol level, the attacks to force such a change are going to intensify in the years to come.

In an op-ed piece titled, “Get Ready For The ‘No-Buy’ List,” David Sacks, the founding COO of PayPal, wrote:

“Kicking people off social media deprives them of the right to speak in our increasingly online world. Locking them out of the financial economy is worse: It deprives them of the right to make a living. We have seen how cancel culture can obliterate one’s ability to earn an income, but now the canceled may find themselves without a way to pay for goods and services. Previously, canceled employees who would never again have the opportunity to work for a Fortune 500 company at least had the option to go into business for themselves. But if they cannot purchase equipment, pay employees, or receive payment from clients and customers, that door closes on them, too.”

This observation is 100% accurate and mirrors the Chinese social credit system, which is a harbinger of a soon-to-be-global trend, especially as the wave of stakeholder capitalism sweeping the private sector intensifies.

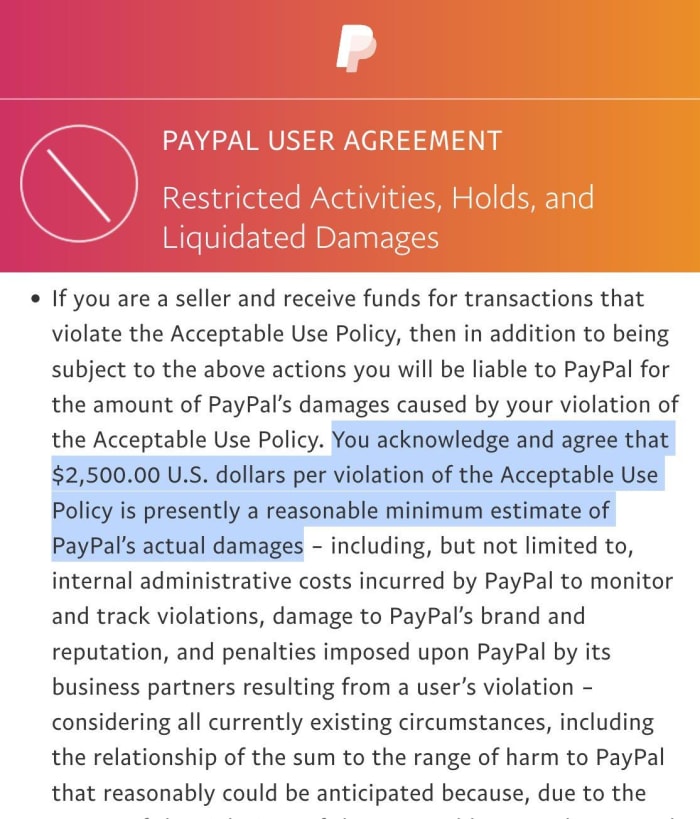

The term “stakeholder capitalism” is a euphemism for fascism and is used to control private companies through “woke” economic metrics like environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores. Adherence to woke capitalism is then indirectly forced upon the customers of the companies in question, with dissent being punished by denial of services or even financial penalties. PayPal once again surfaces as a textbook example of this. In September, it announced a policy through which it intended to fine users $2,500 for sharing “misinformation” online. Last time I checked, PayPal was neither a content moderation platform nor a social media company.

Following a social media backlash against this proposed policy, PayPal then issued a statement citing that the policy was put out erroneously and as a result would not be implemented. Well, three weeks after backtracking on this policy, PayPal re-introduced the $2,500 fine in its newly-updated policy. The $2,500 fine was quietly added to its terms of service after the social media driven furor against it had disappeared. As if that’s not enough, PayPal added a clause that allows it to “freeze” all the money in your accounts for up to six months, “if reasonably needed to protect against the risk of liability or if you have violated our Acceptable Use Policy.”

What we are witnessing is the gradual roll out of a Chinese Communist Party style social credit system. Take this as an early warning, especially in this era where “software is eating the world” and everything from banking to shopping has migrated to digital platforms.

Escaping Sanctions

“Whoever controls the volume of money in any country is absolute master of all industry and commerce.”

–James A. Garfield

Financial censorship is not exclusive to individuals and organizations but it is also extended to countries in the form of sanctions. They are also preferred as an acceptable alternative to military conflict since they are an avenue for non-kinetic power projection and are thus weapons of economic warfare.

The goal of economic sanctions is to impoverish and sicken the civilians of the sanctioned nation with the intention of pressuring the government of the sanctioned country into compliance in its hopes of avoiding civil unrest. Unfortunately, this hardly happens and as a result it’s the ordinary citizens that bear the brunt of sanctions and not the targeted politicians.

Economic sanctions are enabled by the centralized nature of the financial infrastructure of the fiat monetary system which is mainly controlled by the U.S. and the EU. One of the economic warfare tools in their arsenal is the SWIFT network. SWIFT is an international bank messaging system which has been operational since the 1970s that enables the transmission of almost $5 trillion globally every day. This system enables financial institutions to send and receive information about financial transactions in a secure, standardized environment.

Since the dollar is the global reserve currency, SWIFT facilitates the international dollar system. Although SWIFT is headquartered in Belgium, dollar dominance gives the U.S. a great deal of leverage over other countries. As a result of this dominance, the U.S. is able to use SWIFT as a financial weapon against nation states like Russia and Iran that violate “the rules based order.” Deplatforming or removing a country from SWIFT is basically cutting it off economically from trading with the rest of the world.

In stark contrast to this, Bitcoin is a fully-decentralized digital currency and peer-to-peer payments system that is not under the control of any nation state. According to a report titled, “The Treasury 2021 Sanctions Review” by the U.S. Treasury Department, between 2001 and 2021 the number of sanctions that were imposed by the U.S. Treasury had increased by a whopping 933%! In a world of increasing weaponization of the dollar and centralized financial infrastructure, nation state adoption of Bitcoin is a matter of national security.

In his article titled, “Why India Should Buy Bitcoin,” Balaji Srinivasan made the following remark:

“It is this property (referring to Bitcoin’s decentralization) that makes Bitcoin so precious for safeguarding Indian national security. A network that cannot be shut down by any state is a network that India and its diaspora can rely upon in times of conflict. For the same reason that Germany recently repatriated 3,378 tons of gold from the United States, India should prioritize national support for digital gold as a financial rail of last resort in a situation like the 2008 financial crisis or the 2020 COVID crash…Remember also that India has had a multi-millennia long love affair with gold, and is the world’s largest importer of gold. Gold was never a threat to India; gold has always been an asset for India. And Bitcoin is valuable for all the same reasons gold is valuable. It’s an internationally accepted store of value, it’s highly scarce, and it’s a so-called bearer instrument that can’t be seized with a keypress.”

I would also add that Bitcoin adoption at the nation state level is a shield against being deplatformed from financial payment rails like SWIFT. Sanctions have downstream ripple effects that negatively affect everyone tied to a particular country, industry or company that would have been sanctioned. Bitcoin’s censorship resistance shields the citizens of a sanctioned country from the crippling effects of sanctions, and insulates an entire nation’s economy from being unjustifiably attacked. By leveraging off of Bitcoin’s decentralization and censorship resistance people living in sanctioned countries are able to use it in lieu of the dollar for trade and an alternative payments rail to SWIFT.

In late February, the EU along with the U.S., Australia, Canada and Japan agreed to disconnect some Russian banks from the SWIFT network as part of restrictive measures meant to prevent the Russian central bank from circumventing sanctions that had been imposed on Russia as a result of its “military operation” in Ukraine. In a bid to pile more pressure on Russia to cease its “military operation,” Western powers seized Russia’s $640 billion worth of foreign currency reserves.

The implications of this unprecedented move are much bigger than the deplatforming from SWIFT but in my opinion this was the death knell for the risk-free status of U.S. treasuries, which central banks around the world hold. Not only is the entire premise of holding reserves nullified but this action has also proven that a sovereign country’s reserves can be confiscated at the drop of a hat. What had previously been regarded as safe and risk-free assets became risk free no more as non-existent credit risk was replaced by very real confiscation risk. What good are reserves that you can’t access when you need them?

To quote a remark from an article in the Wall Street Journal:

“Barring gold, these assets (i.e. forex reserves) are someone else’s liability—someone who can just decide they are worth nothing…If currency balances were to become worthless computer entries and didn’t guarantee buying essential stuff, Moscow would be rational to stop accumulating them and stockpile physical wealth in oil barrels, rather than sell them to the West.”

The financial censorship of Russia may seem justified today, but is there any guarantee that the weaponization of the financial system will not be abused in future? Every country that doesn’t want to become vulnerable to “denial-of-service attacks” will need to hold bitcoin in its treasury as a matter of national security. This also includes countries that aren’t sanctioned as they still need to diversify and limit their geopolitical risk in a vastly-polarized world. The same also holds true for individual citizens as they are the collateral damage when economic warfare is unleashed on their countries.

A nation cannot be truly sovereign if its financial destiny is controlled by another nation. The risk of being deplatformed from the current dollar-based fiat monetary system either via SWIFT, the IMF or private companies like PayPal continues to grow each day, both for nation states and individuals alike. While the IMF or SWIFT aren’t institutions that deal directly with the public, they do have great influence on the financial well being of a country. Great consideration needs to be made when deciding which assets to acquire in order to maintain individual sovereignty and defend your freedom to transact in the face of an attack. Bitcoin is currently the only financial asset that can be used as a defense against financial censorship at an individual level as well as at a nation state level.

Had the Russian central bank’s reserves been in bitcoin, no nation would have had the ability to arbitrarily freeze or seize them. On the flip side, this event may be the dollar system’s Waterloo and could lead to rapid de-dollarization by countries seeking to reduce their vulnerability to the U.S.’s control.

Attacks On Bitcoin Will Increase In 2023

“A lot of people automatically dismiss e-currency as a lost cause because of all the companies that failed since the 1990’s. I hope it’s obvious it was only the centrally controlled nature of those systems that doomed them. I think this is the first time we’re trying a decentralized, non-trust-based system.”

–Satoshi Nakamoto

In conclusion, as the curtain comes down on 2022, it’s clear from the few examples that we explored in this essay that financial censorship is a huge problem of great concern given its increased usage with no signs of slowing down.

Financial censorship will continue to be one of the most-preferred levers that the state, big tech and bankers will use to silence critics as well as to force compliance with authoritarian policies. As the relationship between the state and “private sector” players gets cozier with regards to financial censorship, our society will continue its slow creep toward a dystopian digital feudalistic future.

The censors are not ignoring Bitcoin anymore and are taking active steps to capture it and/or restrict its usage as much as possible. Senator Warren’s Digital Asset Anti-Money Laundering bill along with the EU’s Markets In Crypto Assets law (MiCA) are two examples of ongoing attempts at regulatory capture, where the low-hanging fruit of fiat on/off ramps are the initial targets. Given everything that transpired this year, it would be naive to expect the state and its private sector allies to abandon their plans to destroy Bitcoin in the coming year.

That said, there is plenty of light at the end of the tunnel. With each attack that the State throws at Bitcoin, the network gets more resilient and stronger. Every attempt at banning Bitcoin, or destroying it, or financially censoring dissenters will have the opposite effect of further substantiating the reason for Bitcoin’s existence. These “free marketing campaigns” will drive home the importance of decentralization and censorship resistance in a more effective way.

The centralized nature of the fiat monetary system and its dependency on trusted third parties is both its strength (as this is how financial censorship is enforced) and its Achilles heel (as this is what Bitcoin dematerialized). In the coming year, as more people get canceled financially, it’s incumbent upon us to build more user-friendly tools that enhance financial privacy, develop Bitcoin circular economies and more Bitcoin-focused educational content. Reducing the Bitcoin learning curve, coupled with enhanced financial privacy and thriving Bitcoin circular economies, will be a great bulwark against attacks from the censors.

In a February 1995 email, Wei Dai, the cryptographer who invented B-Money, which was referenced in the Bitcoin white paper, perfectly captured the spirit of the above solution when he wrote the following:

“There has never been a government that didn’t sooner or later try to reduce the freedom of its subjects and gain more control over them, and there probably never will be one. Therefore, instead of trying to convince our current government not to try, we’ll develop the technology that will make it impossible for the government to succeed. Efforts to influence the government (e.g., lobbying and propaganda) are important only in so far as to delay its attempted crackdown long enough for the technology to mature and come into wide use. But even if you do not believe the above is true, think about it this way: If you have a certain amount of time to spend on advancing the cause of greater personal privacy, can you do it better by using the time to learn about cryptography and develop the tools to protect privacy, or by convincing your government not to invade your privacy?”

Bitcoin’s censorship resistance presents a viable option to both individuals and countries alike to withstand financial deplatforming and maintain sovereignty as well as neutrality in a highly-polarized and cancel-culture driven world. Despite the prevailing bear market, Bitcoin’s censorship resistance remains unchanged. Having a Bitcoin “insurance fund” is the most prudent thing one can do.

As Satoshi Nakamoto wrote, “It might make sense just to get some in case it catches on.”

This is a guest post by Kudzai Kutukwa. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.