SANTIAGO, Oct 29 (IPS) – The production of solar energy by means of panels installed on small farmers’ properties or on the roofs of community organisations is starting to directly benefit more and more farmers in Chile.

This energy enables technified irrigation systems, pumping water and lowering farmers’ bills by supporting their business. It also enables farmers’ cooperatives to share the fruits of their surpluses.

The huge solar and wind energy potential of this elongated country of 19.5 million people is the basis for a shift that is beginning to benefit not only large generators.

The potential capacity of solar and wind power generation is estimated at 2,400 gigawatts, which is 80 times more than the total capacity of the current Chilean energy matrix.

Two farming families

Fanny Lastra, 55, was born in the municipality of Mulchén, 550 kilometres south of Santiago, located in the centre of the country in the Bío Bío region. She has lived in the rural sector of Mirador del Bío Bío in the town since she was 8.

“We won a grant of 12 million pesos (US$12,600) to install a photovoltaic system with sprinklers to make better use of the little water we have on our five-hectare farm and have good alfalfa crops to feed the animals,” she told IPS from her home town.

She refers to the resources provided to applicants who are selected on the basis of their background and the situation of their farms by two government bodies, mostly through grants: the National Irrigation Commission (CNR) and the Institute for Agricultural Development (Indap).

“Before we had to irrigate all night, we didn’t sleep, and now we can optimise irrigation. The panel gives us the energy to expel the water through sprinklers. In the future we plan to apply for another photovoltaic panel to draw water and fill a storage pool,” Lastra said.

The area has received abundant rainfall this year, but a larger pond would allow to store water for dry periods, which are increasingly recurrent.

“We have water shares (rights), but there are so many of us small farmers that we have to schedule. In my case, every nine days I have 28 hours of water. That’s why we applied for another project,” she said.

Lastra works with her children on the plot, which is mainly dedicated to livestock.

The conversion of agricultural land like hers into plots for second homes, which is rampant in many regions of Chile, has also reached Bío Bío and caused Lastra problems. For example, dogs abandoned by their owners have killed 50 of her lambs in recent times.

That is why she will gradually switch to raising larger livestock to continue with Granny’s Tradition, as she christened her production of fresh, mature cheeses and dulce de leche.

Marisol Pérez, 53, produces vegetables in greenhouses and outdoors on her half-hectare plot in the town of San Ramón, within the municipality of Quillón, 448 kilometres south of Santiago, also in the Bío Bío region.

In February 2023 she was affected by a huge fire. “Two greenhouses, a warehouse with motor cultivators, fumigators and all the machinery burnt down. And a poultry house with 200 birds that cost 4500 pesos (US$ 4.7) each. Thank God we saved part of the house and the photovoltaic panel,” She told IPS from his home town.

Pérez has been working the land with her sister and their husbands for 11 years.

“We started with irrigation and a solar panel. After the fire we reapplied to the CNR. As the panel didn’t burn, they helped us with the greenhouse. The government gives us a certain amount and we have to put in at least 10%,” she explained.

The first subsidy was the equivalent of US$1,053 and the second, after the fire, was US$842. With both she was able to reinstall the drip system and rebuild the greenhouse, now made of metal.

“Having a solar panel allows us to save a lot. Before, we were paying almost 200,000 pesos (US$210) a month. With what we saved with the panel, we now pay 6,000 pesos (US$6.3)”, she explained with satisfaction.

In her opinion, “the solar panel is a very good thing. If I don’t use water for the greenhouses, I use it for my house. We live off what we harvest and plant. That’s our life. And I am happy like that,” she said.

The cases of one cooperative and two municipalities

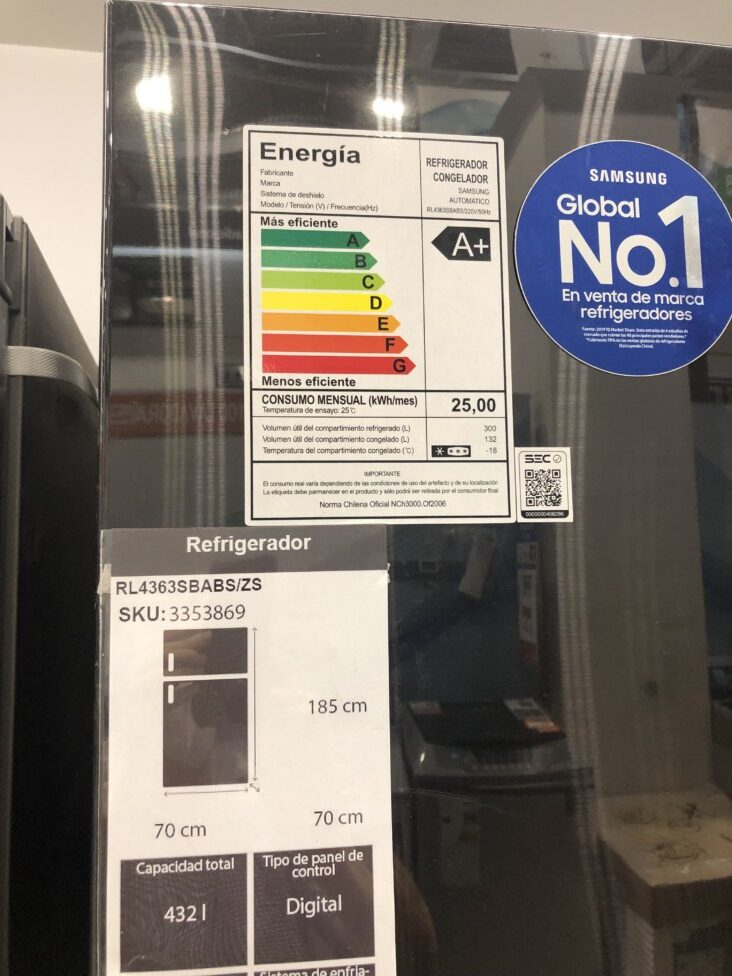

The proliferation of solar panels is also due to the drop in their price. Solarity, a Chilean solar power company, reported that prices are at historic lows.

In 2021 its value per kilowatt (kWp) was 292 dollars. It increased to 300 in 2022, then dropped to 202 and reached 128 dollars in 2024.

In 2021 the Cooperativa Intercomunal Peumo (Coopeumo) commissioned the first community photovoltaic plant in Chile. Today it has 54.2 kWp installed in two plants, with about 120 panels in total.

The energy generated is used in some of its own facilities and the surplus is injected into the Compañía General de Electricidad (CGE), a private distributor, which pays its contribution every month.

This amount contributes to improving support for its 350 members, all farmers in the area, including technical assistance, the sale of agricultural inputs, grain marketing and tax consultancy.

Coopeumo’s goals also include reducing carbon dioxide (C02) emissions into the atmosphere and benefiting its members.

It also benefits the municipalities of Pichidegua and Las Cabras, located 167 and 152 kilometres south of Santiago, as well as school, health and neighbourhood establishments.

“The energy savings in a typical month, like August 2024, was 492,266 pesos (US$518),” said Ignacio Mena, 37, and a computer engineer who works as a network administrator for Coopeumo, based in the municipality of Peumo, in the O’Higgins region, which borders the Santiago Metropolitan Region to the south.

Interviewed by IPS at his office in Pichidegua, he said the construction of the first plant cost the equivalent of US$42,105, contributed equally by Coopeumo and the private foundation Agencia de Sostenibilidad Energética.

Constanza López, 35, a risk prevention engineer and head of the environmental unit of the Las Cabras municipality, appreciates the contribution of the panels installed on the roof of the municipal building. They have an output of 54 kilowatts and have been in operation since 2023.

“We awarded them through the Energy Sustainability Agency. They funded 30 percent and we funded the rest,” she told IPS at the municipal offices. “This year is the first that the programme is fully operational and we should reach maximum production,” she said.

In the case of the municipality of Las Cabras, the estimated annual savings is about US$10,605.

Panels and family farming, a virtuous cycle

There is a virtuous cycle between the use of panels and savings for small farmers. The Ministry of Energy estimates this saving at around 15% for small farms.

“The use of solar technology for self-consumption is a viable alternative for users in the agricultural sector. More and more systems are being installed, which make it possible to lower customers‘ electricity bills,” the ministry said in a written response.

Since 2015, successive governments have promoted the use of renewable energy, particularly photovoltaic systems for self-consumption, within the agricultural sector.

“There has been a steady growth in the number of projects using renewable energy for self-consumption. In total, 1,741 irrigation projects have been carried out with a capacity of 13,852 kW and a total investment of 59,951 million pesos (US$63.1 million),” the ministry said.

The CNR told IPS that so far in 2024 it has subsidised more than 1,000 projects, submitted by farmers across Chile.

“This is an investment close to 78 billion pesos (US$82.1 million), taking into account subsidies close to 62 billion pesos (US$65.2) plus the contribution of irrigators,” it said.

Of these projects, at least 270 incorporate non-conventional renewable energies, “such as photovoltaic systems associated with irrigation works”, it added.

According to the National Electricity Coordinator, the autonomous technical body that coordinates the entire Chilean electricity system, between September 2023 and August 2024, combined wind and solar generation in Chile amounted to 28,489 gigawatt hours.

In the first quarter of 2024, non-conventional renewable energies, such as solar and wind among others, accounted for 41% of electricity generation in Chile, according to figures from the same technical body.

© Inter Press Service (2024) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Source link