click to enlarge

Courtesy of Largest Heart

Nonprofit Largest Heart distributes fentanyl test strips in Orange County to help prevent accidental overdose.

When Peter Cook was in the throes of alcoholism seven years ago, he didn’t imagine he would eventually work to help others who similarly lived and suffered from addiction. In 2017, Peter’s brother Andrew gave him the push and resources he needed to get help and begin his path towards recovery.

Just weeks after, however, Andrew unexpectedly passed away in southern Chile, while on vacation. According to his obituary, Andrew was just 39 years old, a “dedicated Christian” and an English teacher.

For Peter, a resident of Winter Garden, his brother’s sudden passing was a tragedy that led him to where he is today, working by day as the Director of Business Development for Central Florida Behavioral Hospital and as head of a local nonprofit. “Where passion meets purpose,” he told Orlando Weekly.

On his brother’s birthday, in August 2018, Cook officially formed his local nonprofit organization, Largest Heart, a grassroots harm reduction project. Cook “literally Googled ‘how to start a nonprofit,’” he admitted sheepishly, but also with pride.

Earlier this year, Largest Heart was one of two organizations, along with Project Opioid, that was chosen by the Orange County government to lead a new effort to prevent accidental drug overdose.

Over the last decade, fatal drug overdoses in the county have surged more than 250 percent, from 175 deaths in 2014 to roughly 450 last year. A majority are tied to illicit forms of the opioid fentanyl, which is largely coming from U.S. citizens (not migrants) smuggling it across legal points of entry at the U.S. Southern Border, according to immigration authorities.

The idea of Largest Heart’s project, called “Test Before You Try,” is to expand access to fentanyl test strips: small, inexpensive paper strips that can tell you whether there is fentanyl in your drugs. They’re simple to use, about 96 to 100 percent accurate when used correctly, and can save lives.

Until last year, these strips were technically illegal to have, sell or give away in Florida, simply due to being classified under old state statutes as “drug paraphernalia.” State lawmakers in Florida, and over two dozen other states with similar statutes on the books, however, have altered their state laws on paraphernalia in recent years to change that.

So far, Largest Heart has distributed over 38,000 fentanyl testing kits throughout the county, which (thanks to a partnership with DanceSafe) contain testing strips as well as instructions for how to use them.

Cook stressed that distributing these kits is not a push to use drugs — “We don’t encourage drug use,” he affirmed — but to make sure that if you, a friend or a roommate does use, they’re doing so safely, without risking their life. “It’s an empowerment program,” he explained.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid up to 50 times more potent than the illicit opioid heroin, has driven the country’s overdose crisis in recent years, killing nearly 75,000 people in the U.S. last year alone.

It can happen to anyone

What’s most dangerous about this potent drug is where it’s being found. Lab testing from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) found that 7 out of every 10 counterfeit pills they seized last year contained a lethal dose of fentanyl.

Just two milligrams, comparable to just a few grains of table salt, can be deadly. And it’s been found laced into a wide range of illegally produced drugs, including drugs like cocaine, meth, fake pills marketed by dealers under different names, and unregulated forms of marijuana.

What Largest Heart is attempting to do is “not condemning somebody for making a bad decision,” said Cook, referring to illicit drug use, “but educating them.” Making sure that if someone does choose to take a pill at a party or smoke a blunt, they’re not unknowingly putting their life on the line. Substance use experts have warned that you don’t have to have a drug addiction or even regularly use drugs in order to accidentally lose your life.

You can be a teenager or college student who, facing peer pressure, takes a pill someone hands you at a party. You’re told it’s Xanax — a central nervous system depressant commonly prescribed for anxiety — but it’s not. You don’t know this, of course, so you take the pill. Your limbs become heavy. Your face becomes clammy, pale or ashen. Your breathing slows, then stops. You lose consciousness. And you never wake up.

It’s not just a Lifetime movie or some D.A.R.E ad. It’s an actual horror story playing out across the country, quietly devastating parents, friends and communities. Although drug use among youth, specifically, has declined in recent years, teen overdose rates have surged. Counterfeit prescription pills containing fentanyl are believed to be a contributing cause.

Although drug use among youth has declined in recent years, teen overdose rates have surged.

According to data from the Orange County Medical Examiner’s Office, reviewed by Orlando Weekly, at least four teenagers in Orange and Osceola Counties have died of drug overdose this year alone. All four deaths involved fentanyl, and were marked as accidental deaths. In total, the office has identified 263 drug-involved deaths in Orange and Osceola counties this year so far, with fentanyl specifically involved in the vast majority.

“Anytime somebody buys a pill off the street, they should assume it’s more likely that it’s contaminated with fentanyl,” Dr. Thomas Hall, director of the Orange County Office for a Drug-Free Community, told Orlando Weekly earlier this year.

Several adults who died of fatal drug overdose this year were identified by the Medical Examiner’s Office as “transient,” meaning they were homeless. But the vast majority of people who died had a listed home address.

Overdose deaths surged dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic, as people found themselves cut off from others, struggling with mental health, and more vulnerable to using drugs and alcohol to cope. Those who used drugs were also more likely to use them alone, and therefore did not have someone around to call 911 or administer Narcan (a life-saving opioid overdose reversal drug) if they collapsed.

In Orange County, drug overdose deaths reached their peak in 2021. More than 500 people died of drug overdose that year, up from 172 deaths in 2014 and 342 deaths in 2019. The number of fatal overdoses has declined some since, with a slight increase documented last year, but the number of lives lost has remained above pre-pandemic levels.

“We’ve never seen anything like it,” said Cook. “We’re gonna lose a generation of kids to deadly fentanyl.”

A community effort

The fentanyl test strip distribution effort led by Cook’s nonprofit Largest Heart is being funded by a small portion of what Orange County has received so far through national settlements with opioid manufacturers and distributors.

Altogether, the county will receive an estimated $60 million payout from those settlements, distributed over the next 15 to 18 years. The county has already earmarked funds for projects such as overdose awareness campaigns for adults and youth, a mobile medication-assisted treatment clinic for opioid addiction (expected to launch next month), and a new addiction treatment program that just launched this month in Parramore for uninsured residents.

Project Opioid, an Orlando-based profit also focused on reducing overdose deaths, has also received funds to distribute fentanyl test strips. They’re focusing on passing out fentanyl test strips downtown outside nightclubs and bars on the weekends.

Largest Heart’s program has been approved for $61,000 in funding, according to Cook, which comes through reimbursement from the county. “Largest Heart pays for this all upfront,” said Cook, who admitted they’re operating “on a shoestring budget.”

Since March, Largest Heart has been passing out fentanyl test strip kits at community events, including 8,000 at Orlando’s Juneteenth Celebration, and has also given them away to local businesses or organizations that ask, such as food pantries and the LGBT+ Center Orlando.

It’s become a community effort. Park Ave CDs, one of Orlando’s most beloved indie music retailers, has been “one of our best community partners,” Cook gushed. “They are so about protecting and loving on this community in Orlando. It’s absolutely amazing.”

click to enlarge

Park Ave CDS/Instagram

An Instagram post from Park Ave CDs promoting harm reduction supplies the store gives out to help keep the community safe.

Another surprise: “Law enforcement loves them,” he added. The library system is also interested in getting kits to pass out, and local schools, grappling with their own role in preventing accidental overdose among students, have also shown interest. “We had elementary schools requesting these,” Cook said.

Not having an advertising budget for Test Before You Try, he admitted, is one of their biggest challenges in spreading the word. In addition to fentanyl test strips, they’ve also distributed Narcan, the opioid overdose reversal medication. Narcan, or its generic version naloxone, can be purchased from places like Publix, or you can get it for free at different access sites throughout the state, or request it via mail.

Beyond distribution, the idea is to reduce stigma and create openings for conversations about drug use and harm reduction. It could ultimately be a cost-saving effort, too. When or if someone overdoses, the ambulance costs, healthcare costs and other criminal justice system costs can add up for communities.

Similarly, drug addiction can result in lost productivity, health conditions and reduced quality of life, and becomes more costly to treat as conditions become more severe or chronic. Nationally, fatal opioid overdose can cost hundreds of billions of dollars each year, research has found, while treatment for addiction and harm reduction strategies such as fentanyl test strips can be more cost-effective.

Cook’s organization recently secured an agreement with Volusia County to expand their fentanyl test strip distribution there. He’s currently in talks with the Osceola County government as well, saying, “My goal is to take this statewide.”

He’s been speaking with state legislators in the area who might be interested in sponsoring a request for state funds. One of them is Democratic Sen. Geraldine Thompson, who hosted the city’s Juneteenth celebration in Orlando. A legislative aide for Thompson confirmed the senator is considering the request, but has not yet made a decision on whether to sponsor.

Cook admitted, due to stigma, sometimes you have to craft your pitch for fentanyl test strip kits on the fly, depending on who you’re talking to. But it’s not always hard. Cook said one grandmother came up to him at an event his nonprofit attended and cried on his shoulder, thanking him for his work. Her teenage grandson had died, he recalled, after smoking marijuana laced with fentanyl.

For a young person headed to college who doesn’t use drugs, and doesn’t plan to, he explains to them, “This isn’t for you. This is for your roommate.” For parents, he tells them, “Like, I know your kid’s never gonna smoke weed, but if they do, here you go.”

Ultimately, it’s laying out the stakes: Thousands of people die of accidental overdose each year. And you never know who could be next.

click to enlarge

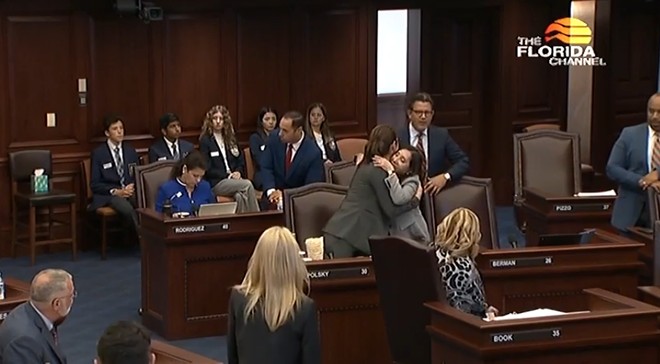

The Florida Channel

Florida Sen. Tina Polsky hugging Democratic colleague Sen. Lori Berman after a bill to decriminalize fentanyl testing equipment passes on March 29, 2023.

Need help?

September is National Recovery Month. If you or a loved one is struggling with substance misuse, you’re not alone.

Subscribe to Orlando Weekly newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | or sign up for our RSS Feed