[ad_1]

Over the last several years, fusion power has gone from the butt of jokes — always a decade away! — to an increasingly tangible and tantalizing technology that has drawn investors off the sidelines.

The technology may be challenging to master and expensive to build today, but fusion promises to harness the nuclear reaction that powers the sun to generate nearly limitless energy here on Earth. If startups are able to complete commercially viable fusion power plants, then they have the potential to upend trillion-dollar markets.

The bullish wave buoying the fusion industry has been driven by three advances: more powerful computer chips, more sophisticated AI, and powerful high-temperature superconducting magnets. Together, they have helped deliver more sophisticated reactor designs, better simulations, and more complex control schemes.

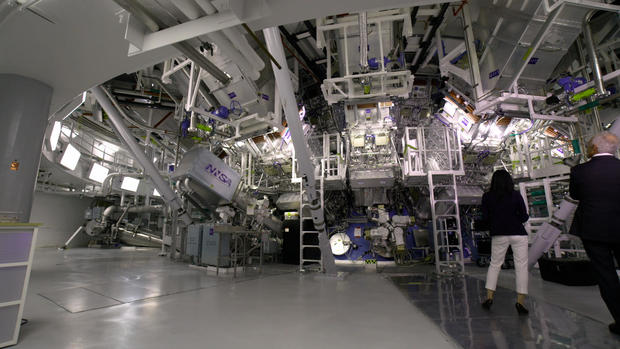

It doesn’t hurt that, at the end of 2022, a U.S. Department of Energy lab announced that it had produced a controlled fusion reaction that produced more power than the lasers had imparted to the fuel pellet. The experiment had crossed what’s known as scientific breakeven, and while it’s still a long ways from commercial breakeven, where the reaction produces more than the entire facility consumes, it was a long-awaited step that proved the underlying science was sound.

Founders have built on that momentum in recent years, pushing the private fusion industry forward at a rapid pace.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems

Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) has raised about a third of all private capital invested in fusion companies to date. Its latest round, which closed in August, added $863 million to its coffers, bringing its total raised near $3 billion.

CFS’s Series B2 came four years after its $1.8 billion Series B, which helped catapult the company into the pole position. Since then, the startup has been hard at work in Massachusetts building Sparc, its first-of-a-kind power plant intended to produce power at what it calls “commercially relevant” levels.

Techcrunch event

San Francisco

|

October 13-15, 2026

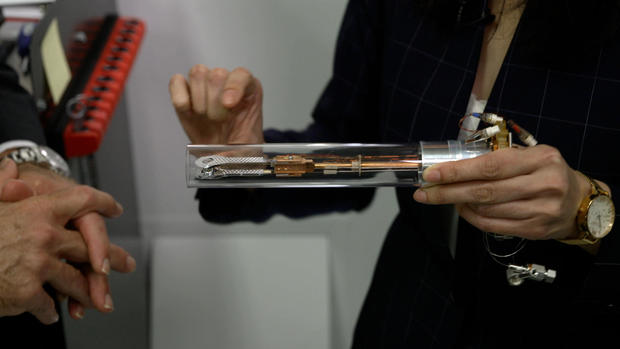

Sparc’s reactor is a tokamak design, which resembles a doughnut. The D-shaped cross section is wound with high-temperature superconducting tape, which, when energized, generates a powerful magnetic field that will contain and compress the superheated plasma. Heat generated from the reaction is converted to steam to power a turbine. CFS designed its magnets in collaboration with MIT, where co-founder and CEO Bob Mumgaard worked as a researcher on fusion reactor designs and high-temperature superconductors.

The Massachusetts-based CFS expects to have Sparc operational in late 2026 or early 2027. Later this decade, the company says it will begin construction on Arc, its commercial power plant that will produce 400 megawatts of electricity. The facility will be built near Richmond, Virginia, and Google has agreed to buy half its output.

CFS is backed by a long list of investors, including Breakthrough Energy Ventures, The Engine, Bill Gates, and others.

TAE Technologies

Founded in 1998, TAE Technologies (formerly known as Tri Alpha Energy) was spun out of the University of California, Irvine by Norman Rostoker. It uses a field-reversed configuration, but with a twist: after the two plasma shots collide in the middle of the reactor, the company bombards the plasma with particle beams to keep it spinning in a cigar shape. That improves the stability of the plasma, allowing more time for fusion to occur and for more heat to be extracted to spin a turbine.

In December 2025, TAE announced that it would merge with President Donald Trump’s social media company, Trump Media & Technology Group. The all-stock transaction would value the combined company at $6 billion. TAE would receive $200 million plus another $100 million upon filing paperwork with the Securities and Exchange Commission. TAE CEO Michl Binderbauer will serve as co-CEO of the combined company alongside Devin Nunes, who had been sole CEO of Trump Media.

The fusion startup had previously raised $150 million in June from existing investors, including Google, Chevron, and New Enterprise. Before the merger, TAE had raised a total of $1.79 billion, according to PitchBook.

Helion

Of all fusion startups, Helion has the most aggressive timeline. The company plans to produce electricity from its reactor in 2028. Its first customer? Microsoft.

Helion, based in Everett, Washington, uses a type of reactor called a field-reversed configuration, where magnets surround a reaction chamber that looks like an hourglass with a bulge at the point where the two sides come together. At each end of the hourglass, they spin the plasma into doughnut shapes that are shot toward each other at more than 1 million mph. When they collide in the middle, additional magnets help induce fusion. When fusion occurs, it boosts the plasma’s own magnetic field, which induces an electrical current inside the reactor’s magnetic coils. That electricity is then harvested directly from the machine.

The company raised $425 million in January 2025, around the same time that it turned on Polaris, a prototype reactor. Helion has raised $1.03 billion, according to PitchBook. Investors include Sam Altman, Reid Hoffman, KKR, BlackRock, Peter Thiel’s Mithril Capital Management, and Capricorn Investment Group.

Pacific Fusion

Pacific Fusion burst out of the gate with a $900 million Series A, a whopping sum even among well-funded fusion startups. The company will use inertial confinement to achieve fusion, but instead of lasers compressing the fuel, it will use coordinated electromagnetic pulses. The trick is in the timing: All 156 impedance-matched Marx generators need to produce 2 terawatts for 100 nanoseconds, and those pulses need to simultaneously converge on the target.

The company is led by CEO Eric Lander, the scientist who led the Human Genome Project, and president Will Regan. Pacific Fusion’s funding might be massive, but the startup hasn’t gotten it all at once. Rather, its investors will pay out in tranches when the company achieves specified milestones, an approach that’s common in biotech.

Shine Technologies

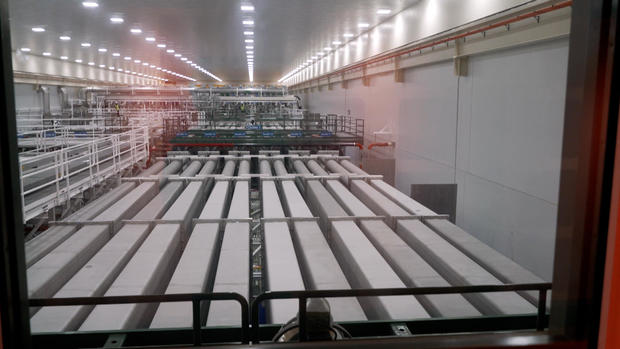

Shine Technologies is taking a cautious — and possibly pragmatic — approach to generating fusion power. Selling electrons from a fusion power plant is years off, so instead, it’s starting by selling neutron testing and medical isotopes. More recently, it has been developing a way to recycle radioactive waste. Shine hasn’t picked an approach for a future fusion reactor, instead saying that it’s developing necessary skills for when that time comes.

The company has raised a total of $778 million, according to PitchBook. Investors include Energy Ventures Group, Koch Disruptive Technologies, Nucleation Capital, and the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.

General Fusion

Now its third decade, General Fusion has raised $462.53 million, according to PitchBook. The Richmond, British Columbia-based company was founded in 2002 by physicist Michel Laberge, who wanted to prove a different approach to fusion known as magnetized target fusion (MTF). Investors include Jeff Bezos, Temasek, BDC Capital, and Chrysalix Venture Capital.

In General Fusion’s reactor, a liquid metal wall surrounds a chamber in which plasma is injected. Pistons surrounding the wall push it inward, compressing the plasma inside and sparking a fusion reaction. The resulting neutrons heat the liquid metal, which can be circulated through a heat exchanger to generate steam to spin a turbine.

General Fusion hit a rough patch in spring 2025. The company ran short of cash as it was building LM26, its latest device that it hoped would hit breakeven in 2026. Just days after hitting a key milestone, it laid off 25% of its staff. CEO Greg Twinney penned an open letter pleading for funding from investors.

In August, they delivered somewhat, injecting $22 million in a pay-to-play round that one investor called “the least amount of capital possible” to keep the General Fusion afloat. Then in November, securities filings in Canada revealed that the company had raised $51.1 million in SAFE notes from nearly 70 investors, the Globe and Mail reported. Altogether, General Fusion has raised $492 million, according to PitchBook.

Tokamak Energy

Tokamak Energy takes the usual tokamak design — the doughnut shape — and squeezes it, reducing its aspect ratio to the point where the outer bounds start resembling a sphere. Like many other tokamak-based startups, the company uses high-temperature superconducting magnets (of the rare earth barium copper oxide, or REBCO, variety). Since its design is more compact than a traditional tokamak, it requires less in the way of magnets, which should reduce costs.

The Oxfordshire, U.K.-based startup’s ST40 prototype, which looks like a large, steampunk Fabergé egg, generated an ultra-hot, 100 million degree C plasma in 2022. Its next generation, Demo 4, is currently under construction and is intended to test the company’s magnets in “fusion power plant-relevant scenarios.” Tokamak Energy raised $125 million in November 2024 to continue its reactor design efforts and expand its magnet business.

In total, the company has raised $336 million from investors including Future Planet Capital, In-Q-Tel, Midven, and Capri-Sun founder Hans-Peter Wild, according to PitchBook.

Zap Energy

Zap Energy isn’t using high-temperature superconducting magnets or super-powerful lasers to keep its plasma confined. Rather, it zaps the plasma (get it?) with an electric current, which then generates its own magnetic field. The magnetic field compresses the plasma about 1 millimeter, at which point ignition occurs. The neutrons released by the fusion reaction bombard a liquid metal blanket that surrounds the reactor, heating it up. The liquid metal is then cycled through a heat exchanger, where it produces steam to drive a turbine.

Like Helion, Zap Energy is based in Everett, Washington, and the company has raised $327 million, according to PitchBook. Backers include Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures, DCVC, Lowercarbon, Energy Impact Partners, Chevron Technology Ventures, and Bill Gates as an angel.

Proxima Fusion

Most investors have favored large startups that are pursuing tokamak designs or some flavor of inertial confinement. But stellarators have shown great promise in scientific experiments, including the Wendelstein 7-X reactor in Germany.

Proxima Fusion is bucking the trend, though, having attracted a €130 million Series A that brings its total raised to more than €185 million. Investors include Balderton Capital and Cherry Ventures.

Stellarators are similar to tokamaks in that they confine plasma in a ring-like shape using powerful magnets. But they do it with a twist — literally. Rather than force plasma into a human-designed ring, stellarators twist and bulge to accommodate the plasma’s quirks. The result should be a plasma that remains stable for longer, increasing the chances of fusion reactions.

Kyoto Fusioneering

With all the startups pursuing fusion power, it was perhaps inevitable that another would pop up to develop components that round out a power plant. The so-called balance of plant, or the parts that sit outside the reactor, range from gyrotrons that heat plasma to heat extraction systems to harvest power from fusion reactions to turn it into electricity.

Kyoto Fusioneering has made an early bet that if even one fusion startup succeeds in generating enough power to sell to the grid, that the industry will need a supplier for the balance of plant and the expertise to integrate it into whichever fusion technologies win out.

Venture capitalists appear to agree, having invested $191 million in Kyoto Fusioneering. Investors include 31Ventures, In-Q-Tel, JIC Venture Growth Investments, Mitsubishi, and Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Investment.

Marvel Fusion

Marvel Fusion follows the inertial confinement approach, the same basic technique that the National Ignition Facility used to prove that controlled nuclear fusion reactions could produce more power than was needed to kick them off. Marvel fires powerful lasers at a target embedded with silicon nanostructures that cascade under the bombardment, compressing the fuel to the point of ignition. Because the target is made using silicon, it should be relatively simple to manufacture, leaning on the semiconductor manufacturing industry’s decades of experience.

The inertial confinement fusion startup is building a demonstration facility in collaboration with Colorado State University, which it expects to have operational by 2027. Munich-based Marvel has raised a total of $162 million from investors including b2venture, Deutsche Telekom, Earlybird, and HV Capital with Taavet Hinrikus and Albert Wenger as angels.

First Light Fusion

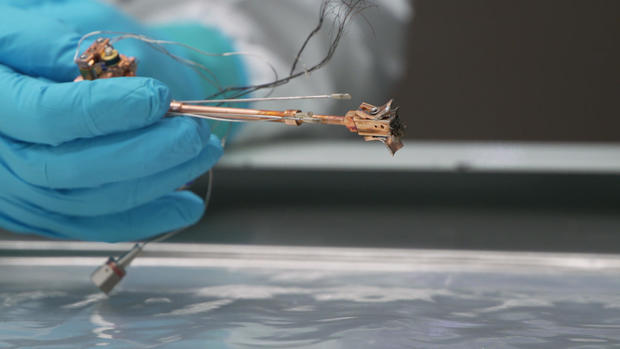

Unlike many other fusion startups, First Light Fusion doesn’t use magnets to generate the conditions necessary for fusion. Instead, it follows an approach known as inertial confinement, in which fusion fuel pellets are compressed until they ignite.

But even then, First Light doesn’t hew to orthodoxy. Most attempts at inertial confinement use lasers to do the dirty work, following the lead of the National Ignition Facility, which produced a groundbreaking experiment in 2022. Rather, First Light fires a projectile at a target using a two-stage gun; the first stage uses gunpowder to fire a plastic piston that compresses hydrogen to 145,000 psi, which then launches the projectile. The target is designed to amplify the force of the impact so it compresses the fuel to the point of ignition.

In March 2025, First Light announced that it would not pursue building its own power plant, instead offering its core technologies to other companies to build one. A spokesperson for First Light said that it is planning to build “pulsed power capability that would act as our demonstrator plant but would have other science and defense applications.” In other words, the company was dropping its plans for a power plan in a quest for revenue.

Based in Oxfordshire, UK, First Light has raised $108 million from investors including Invesco, IP Group, and Tencent, according to PitchBook.

Xcimer

Though nothing about fusion can be described as simple, Xcimer takes a relatively straightforward approach: follow the basic science that’s behind the National Ignition Facility’s breakthrough net-positive experiment, and redesign the technology that underpins it from the ground up. The Colorado-based startup is aiming for a 10-megajoule laser system, five times more powerful than NIF’s setup that made history. Molten salt walls surround the reaction chamber, absorbing heat and protecting the first solid wall from damage.

Founded in January 2022, Xcimer has already raised $100 million, according to PitchBook, from investors including Hedosophia, Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Emerson Collective, Gigascale Capital, and Lowercarbon Capital.

This story was originally published in September 2024 and will be continually updated.

[ad_2]

Tim De Chant

Source link