Total falsehoods: “I want for people to recognize a great job that I’ve done on pricing, on affordability, because we brought prices way down,” said President Donald Trump on Monday. (The White House released a semi-propagandistic fact sheet that same day to bolster the president’s talking points, as all White Houses do at one time or another.)

“We are doing better than we’ve ever done as a country. Prices are coming down and all of that stuff,” he said the week before. “And you know, they talk about different terms for that, but I will tell you that nobody has done what we’ve done in terms of pricing.”

“Walmart just announced that the cost of their standard Thanksgiving meal is reduced by 25 percent this year from last year,” Trump said recently, failing to account for the fact that the price change is due to Walmart…changing the goods offered via their Thanksgiving meal bundle (and drastically shrinking its size) to get prices lower for cost-burdened consumers.

The Reason Roundup Newsletter by Liz Wolfe Liz and Reason help you make sense of the day’s news every morning.

“Since January 2025, the Consumer Price Index has ranged between 3.3 percent and 2.7 percent,” writes National Review‘s Jim Geraghty. “That’s much better than the worst days of the Biden administration in 2022, but that’s also roughly where it was for Biden’s final year in office.”

But Trump, ever a salesman, recognizes which messages are winning for other politicians: It’s affordability season, and you’ve gotta appeal to people’s bottom lines if you want to be taken seriously right now.

The Free Press‘ related entry into this discourse is rather interesting, albeit wrong: “The poverty line, a six-decade-old benchmark, claims to define the threshold to the middle class,” writes Michael W. Green. “The number is a lie.”

Green goes on to promote the idea that a household income of $100,000 is “the new poverty”; that the reason the affordability messaging is so salient is because even households that look well-off on paper are actually struggling to make ends meet; that the ways we measure poverty and economic struggle are way outdated.

“In 1963, Mollie Orshansky, an economist at the Social Security Administration, observed that families spent roughly one-third of their income on groceries,” writes Green. “Since pricing data was hard to come by for many items (e.g., housing), if you could calculate a minimum adequate food budget at the grocery store, you could multiply by three and establish a poverty line. Orshansky presented her findings in 1965. She was drawing a floor, a line below which families were clearly in crisis.” (This is not totally correct; the actual story of how the poverty line was calculated is a bit more complex.)

“For that time, that floor made sense,” continues Green. “Housing was relatively cheap. A family could rent a decent apartment or buy a home on a single income. Healthcare was provided by employers and cost relatively little (Blue Cross coverage cost in the range of $10 per month). Childcare didn’t really exist as a market—mothers stayed home, family helped, or neighbors (who likely had someone home) watched each others’ kids. Cars were affordable, if prone to breakdowns. College tuition could be covered with a summer job.” Today, argues Green, the labor market has transformed, requiring two earners, not one—and thus childcare expenses (for families that end up having kids, which is to say: not everyone). Housing is a larger share of the monthly household budget. Ditto for healthcare. “If you keep Orshansky’s logic—if you maintain her principle that poverty could be defined by the inverse of food’s budget share—but update the food share to reflect today’s reality, the multiplier is no longer three,” argues Green. “It becomes 16. Which means if you measured income inadequacy today the way Orshansky measured it in 1963, the threshold for a family of four—the official poverty line in 2024—wouldn’t be $31,200. If the crisis threshold—the floor below which families cannot function—is honestly updated to current spending patterns, it lands at close to $140,000.”

“The idea that over time we should dynamically multiply a food budget by the inverse of food’s share of the budget to get the poverty line is laughable,” argues American Enterprise Institute’s Scott Winship. “Engel’s law says that as societies grow richer, the food share of the budget falls. But by Green’s logic, the richest possible society is really the poorest. If we got the food share down to 1% of household budgets, we’d need to multiply the food budget by 99 instead of Green’s 16. This multiplier is actually a measure of a society’s affluence!”

I’m persuaded by Winship’s argument that this model is bad and I think Green’s argument sells short the massive quality-of-life gains we’ve had since the ’60s. Success and stability, to my mind, are not defined solely by material objects. But at the same time, the fact that pretty much all of us have little tiny supercomputers in our pockets that connect us to infinite reserves of knowledge (and to each other) is a vast improvement. The fact that household goods are cheap and easy to come by is no small thing (even though we sometimes trick ourselves into believing durability is suffering, when nowadays, a lot of the time, the cost of repair is higher than the cost of replacing). Sure, a lot of people are wasting $150,000 (or more) on educations that, well, maybe they could’ve gotten for “$1.50 in late fees at the public library“—but isn’t it a huge boon to self-starters everywhere that you don’t even need to go to the public library anymore to access that type of knowledge? The worldwide web is a gift to us all (if only we’d stop mainlining 60-second vertical videos).

At the same time, despite his bad model and questionable portrayal of history, Green is correct to identify housing, childcare, healthcare, and education costs as areas that have not gotten better over time to the degree that many of us had hoped. These are extreme pain points for many Americans, particularly for those who find themselves too rich for welfare, but too poor to be able to have much margin. (“Our entire safety net is designed to catch people at the very bottom,” writes Green, accurately, “but it sets a trap for anyone trying to climb out.”)

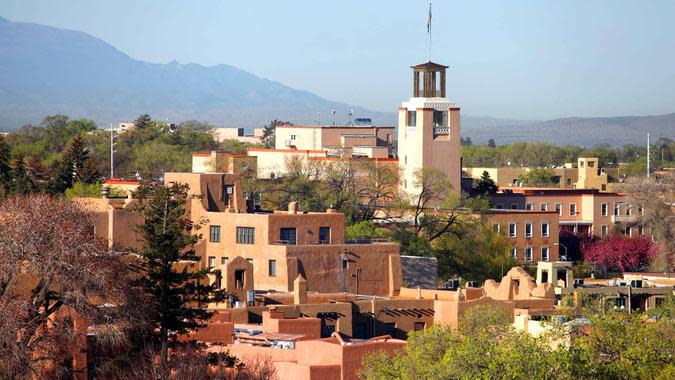

It’s easy to say issues like housing are only bad in large metro areas, not the rest of the country, but roughly 20 percent of the U.S. population lives in a large metro area (20 million in New York, 13 million in L.A., 9 million in Chicago, 8 million apiece in Dallas and Houston). Six percent of the U.S. population lives within the New York metro area alone. And it is a good thing for people to care about agglomeration effects and to want to go where the jobs are, to be upwardly mobile and thus geographically mobile; if the price to doing so is incurring massive housing costs, one response is that those tradeoffs are natural and part of life. Another response is that we’re disincentivizing people who would otherwise be highly productive workers, that we’re making it costlier for them to pursue the most productive use of their time and talent.

It’s the same story with childcare expenses. There’s no way around the fact that childcare requires lots of human labor. But most localities have heaped on burdensome regulations and degree requirements that make it even harder and more expensive to hire competent workers and maintain licensed facilities. One answer to this is for families to have only one earner during the young-kid years, not two; but this comes at great cost to future earnings, and it can be easier to enter and exit at will in some industries than in others. The young-kid years are relatively short (especially as family sizes shrink), but it’s not crazy for families in larger metro areas to feel hit rather hard by the dual needs of childcare and housing.

Perhaps the greatest issue with Green’s writing is that he confuses “poverty” and “economic strain.” It is very possible that dual-earner households making six figures feel economic strain from high childcare, housing, and healthcare costs. But feeling encumbered by tradeoffs is rather different than being poor. We should allow these words to retain their meanings. Affordability discourse is useless if it’s not accurate, and every politician and pundit should strive to accurately describe Americans’ financial realities, not inflate or exaggerate hardship to serve a particular political agenda.

Most of the time, politicians will offer one solution and one solution only: the warm embrace of the state to alleviate people’s financial woes. In reality, getting the state the hell out of the way would help bring down prices in most of the categories people cite as the ones giving them the most trouble.

Scenes from New York: Incoming mayor Zohran Mamdani has asked 179 Eric Adams staffers to resign from their City Hall posts. Mamdani “has already named Dean Fuleihan, a longtime government hand, as his first deputy mayor and has retained the police commissioner, Jessica Tisch,” reports The New York Times. His longtime top aide, Elle Bisgaard-Church, will serve as his chief of staff. (“Ursulina Ramirez, who helped lead Bill de Blasio’s transition in 2013, said Mr. Mamdani’s housecleaning was reminiscent of Mr. de Blasio’s after he succeeded Michael R. Bloomberg,” per the Times.)

QUICK HITS

- Happy Thanksgiving! Look, I like politics, but what I really like is PIE. DM me/email me/sound off in the comments section about the most important issue of all: Which pies are you baking/eating tomorrow? I always make the GoHo, a recipe I adapted from Martha Stewart and have made dozens of times over the years, with elements of pecan but a little more sophistication than your standard pecan-and-corn-syrup getup. This year I am also experimenting with a cranberry curd tart (think tarte au citron but a little tangier, with a delicate hazelnut crust) and a maple chess pie with coffee whipped cream. And, in the spirit of the holiday, let me also mention: I am so deeply grateful for each person who takes time out of their busy day to read this newsletter. I hope it leaves you better informed and even makes you chuckle every once in a while. Cheers to freedom and to pie!

- “My therapist always asks me to transcribe my dreams and the recurring dream I’ve had is standing up in a cafeteria full of women and saying ‘I don’t want children. I want power!’” said Tennessee state representative Aftyn Behn on a recent podcast. And indeed, power she seeks: Behn is running to represent Tennessee’s 7th congressional district and replace U.S. Rep. Mark Green, a Republican, in a special election that will be held on December 2. Maybe it’s just me, but any politician who is so blatant about wanting power immediately rubs me the wrong way. Behn should want to improve the lives of her constituents. It is uncouth to say the quiet part out loud!

- This Jonathan Haidt piece is actually just a rehashing of The Screwtape Letters.

- Black Friday purchases as a recession indicator?

- Gavin Newsom better become a bit more pro-tech mighty fast:

It’s true that California’s economy grew under Newsom, but it has also become a one-trick pony. If AI crashes, Newsom’s presidential hopes will crash with it. pic.twitter.com/UcKdPrGUrL

— Marc Joffe (@joffemd) November 25, 2025

Liz Wolfe

Source link