The Leonid meteor shower is one of the most famous and historically significant celestial events, occurring every November, with tons of meteors available to view.

We’re lucky enough to witness this celestial show from now until Nov. 20. This meteor shower is caused by Earth’s passage through the dusty trail left behind by the comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle. This small comet orbits the Sun roughly every 33 years, creating a river of cosmic stardust in its wake.

How to see the shower

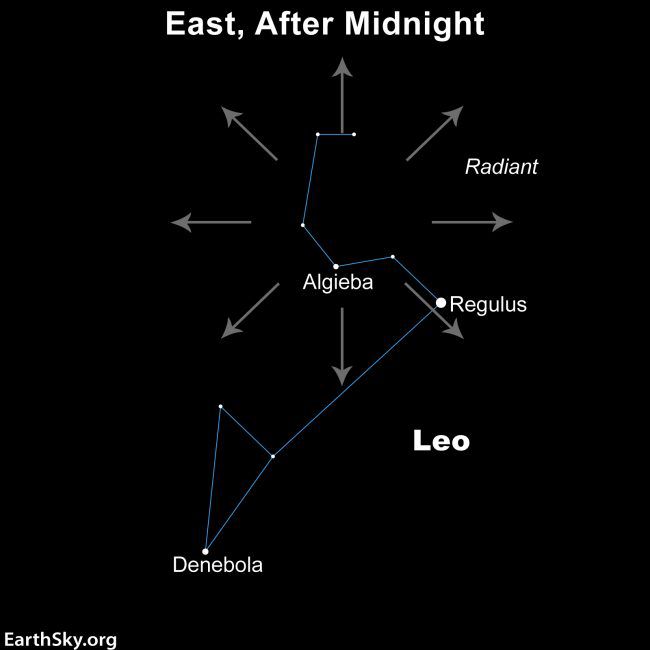

The best time to look is typically in the hours after midnight and before dawn when the constellation Leo climbs highest in the eastern sky. The shower is active throughout this month, but its peak usually occurs around Nov. 18. Below is a forecast loop of cloud cover through early morning of the 21st.

For optimal viewing, find a location far from city lights, lie flat on your back, and simply look up, allowing about 30 minutes for your eyes to adapt to the dark.

Science behind the shower

The Leonids are renowned for their exceptional speed, clocking in at around 158,000 mph, making them one of the fastest annual meteor showers. This high velocity directly results from the comet’s orbit, going around the Sun in the opposite direction to Earth.

Because the comet’s debris hits our atmosphere nearly head-on, the resulting flashes are typically bright and leave behind glowing trails or produce colorful fireballs. These meteors appear brighter than the brightest stars and the planet Venus.

Even in a typical year, when observers might see a modest rate of 10 to 20 meteors per hour, the sheer intensity of the Leonids ensures a captivating display.

Why this shower is so special

The Leonids are in a class of their own among other meteor showers for the sheer volume of meteors to see. While most meteor showers are consistent year over year, the Leonids are capable of bursts of activity where the rate of visible meteors skyrockets to over 1,000 per hour.

This phenomenon occurs approximately every 33 years, coinciding with the comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle’s closest approach to the Sun. During these rare events, Earth passes through a particularly dense, fresh debris field. Historically, these storms have been awesome, with the 1833 and 1966 events being among the most famous, where meteors “fell like rain.”

Our team of meteorologists dives deep into the science of weather and breaks down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.

Meteorologist Nathan Harrington

Source link