Thanksgiving is a time for the gathering of family and friends, for great food, football, and for some, shopping. Most of the time, the weather around the Thanksgiving holiday centers on travel impacts.

Thanksgiving week is one of the busiest travel times of the year, and a little bit of “not so nice weather” can cause a lot of travel headaches.

Many times, the weather is just an inconvenience, but sometimes around Thanksgiving, the weather has been dangerous and even deadly.

What You Need To Know

- Thanksgiving storms are not all about wintry weather

- The transition in seasons can allow for active weather in late November

- Thanksgiving storms can affect even more people due to holiday travel

Though Thanksgiving is celebrated in the later part of fall, we’re still in a time of year with the clash of air masses, we can see some pretty big storm systems. And we’re not just taking snow and wintry precipitation.

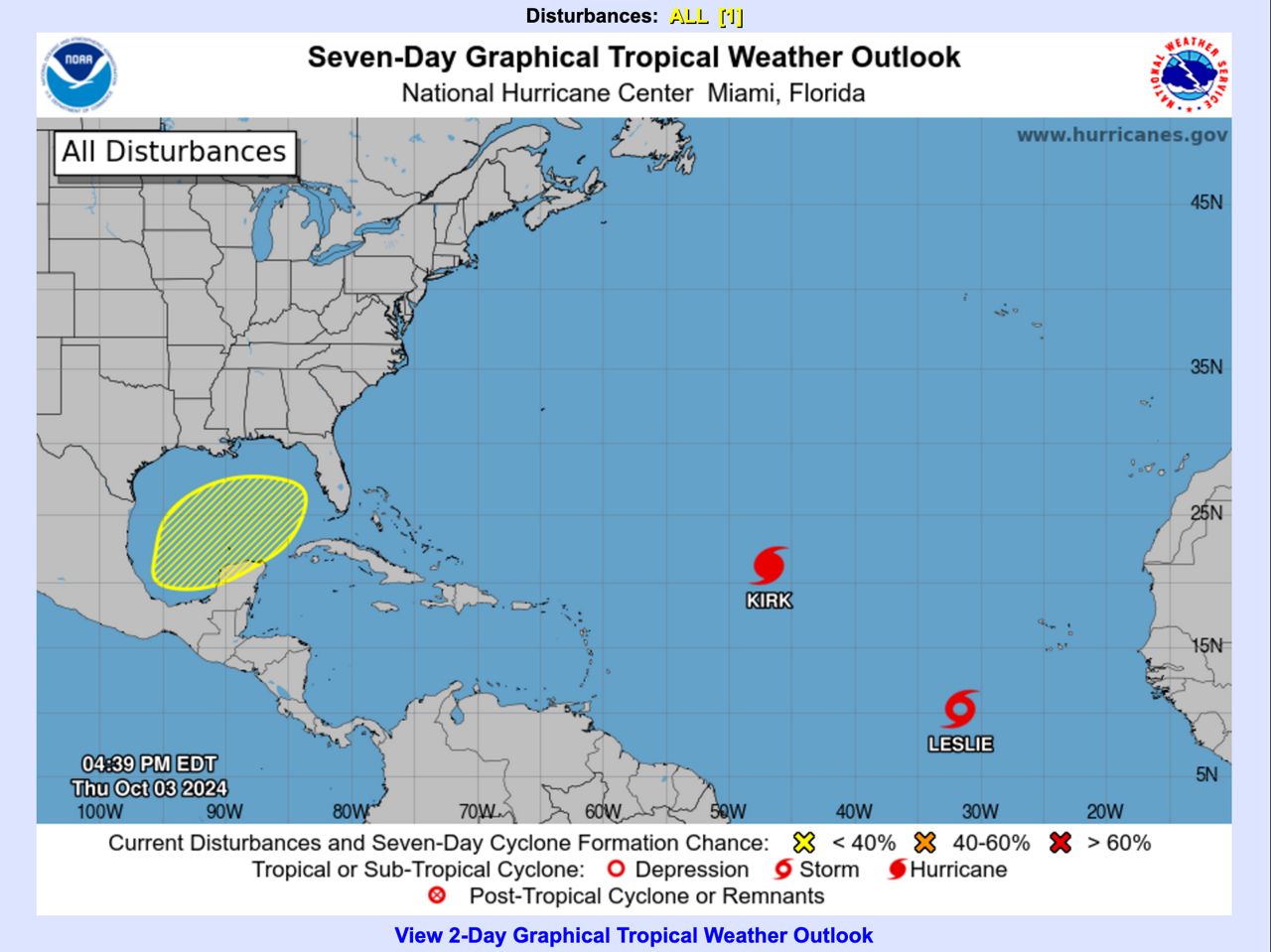

November can see some late season severe weather outbreaks. Not to mention, the hurricane season is still underway in November, not ending until the end of the month.

Here are a few of the major Thanksgiving storms that have impacted the United States in the last 100 years.

Nov. 25, 1926: Thanksgiving Day tornado outbreak

The Thanksgiving Day Tornado Outbreak of 1926 is a perfect example of a late season severe weather outbreak for the Deep South. On Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 25, 1926, there were 14 reported tornadoes across central and eastern Arkansas.

Four of the tornadoes were rated at F3 and F4 on the old Fujita Scale of tornado intensity.

This was the deadliest tornado outbreak in the state of Arkansas until a severe weather outbreak in Jan. 1949.

Arkansas was not the only state hit by this Thanksgiving Day weather system. Louisiana had 11 fatalities, as several tornadoes made their way through that area, as well.

Nov. 24-25, 1950: The Great Appalachian Storm

On the day after Thanksgiving in 1950, an area of low pressure developed along a cold front in southeastern North Carolina. That low would become the storm that would be called The Great Appalachian Storm of 1950.

As the system moved northward, it rapidly strengthened near Washington, D.C. on the morning of Nov. 25. Over time, the storm moved more northwest, more inland, into the Ohio Valley.

The strong low pressure system pulled frigid air down across the eastern U.S. With moisture wrapping into this cold air, snow was reported as far south as Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama. The bulk of the snow occurred across the Ohio Valley, with many locations seeing over two feet of snow in Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Coburn Creek, West Virginia reported 62 inches of snow from the storm. Farther north, the Great Lakes region and parts of the Northeast also saw some snowfall from the storm.

Units of the 112th Engineers of the Ohio National Guard use shovels to help free snow bound streets of Cleveland, Ohio, Nov. 28, 1950. Weekend storm caused one of the worst traffic jams in Cleveland’s history. (AP Photo)

And speaking of the cold air, many reporting stations saw all time record low temperatures for November during this weather event.

As far south as Florida, Pensacola had a low of 22 degrees. It was 16 degrees in Wilmington, North Carolina; 5 degrees in Birmingham, Alabama; 3 degrees in Atlanta and 1 degree in Asheville, North Carolina. The temperature in Louisville, Kentucky and Nashville, Tennessee dropped below zero to -1 degrees.

Looking toward downtown Pittsburgh, Webster Avenue is buried in snow, Nov. 26, 1950, after a record snowfall. The Mellon skyscraper is under construction at left in background. (AP Photo/Walter Stein)

Strong wind was another factor in the storm. Winds at Mount Washington reached 160 mph. A wind gust of 110 mph was reported at Concord, New Hampshire. A gust to 94 mph was recorded in New York City.

These strong winds cause wide spread tree damage and power outages. Along the coast, the strong winds produced coastal flooding. Runways at LaGuardia Airport in New York were flooded when coastal flooding overwashed dikes in the area.

Overall, 22 states were affected by the Storm of 1950. 383 people lost their lives in the storm and it caused over 65 million dollars in damages (almost $1 billion today).

Nov. 24-25, 1971: Thanksgiving snowstorm

21 years later, another early season winter storm would affect some of the same areas as The Great Appalachian Storm of 1950.

On the Thanksgiving Eve, snow started falling across parts of the Northeast U.S. As the snow continued to fall through the night, the precipitation increased and by Thanksgiving afternoon, snowfall totals of 20 to 30 inches of snow were reported across parts of the Catskills and Upper Hudson River Valley.

Pennsylvania saw the most snow from the storm. Albany, New York recorded just under two feet of snow. The storm stranded travelers in the region as they tried to make their way to their Thanksgiving destinations.

Because the air temperature was near the freezing mark during the storm, the system produced a heavy, wet snow. This caused roofs to collapse, tree damage and widespread power outages across the region.

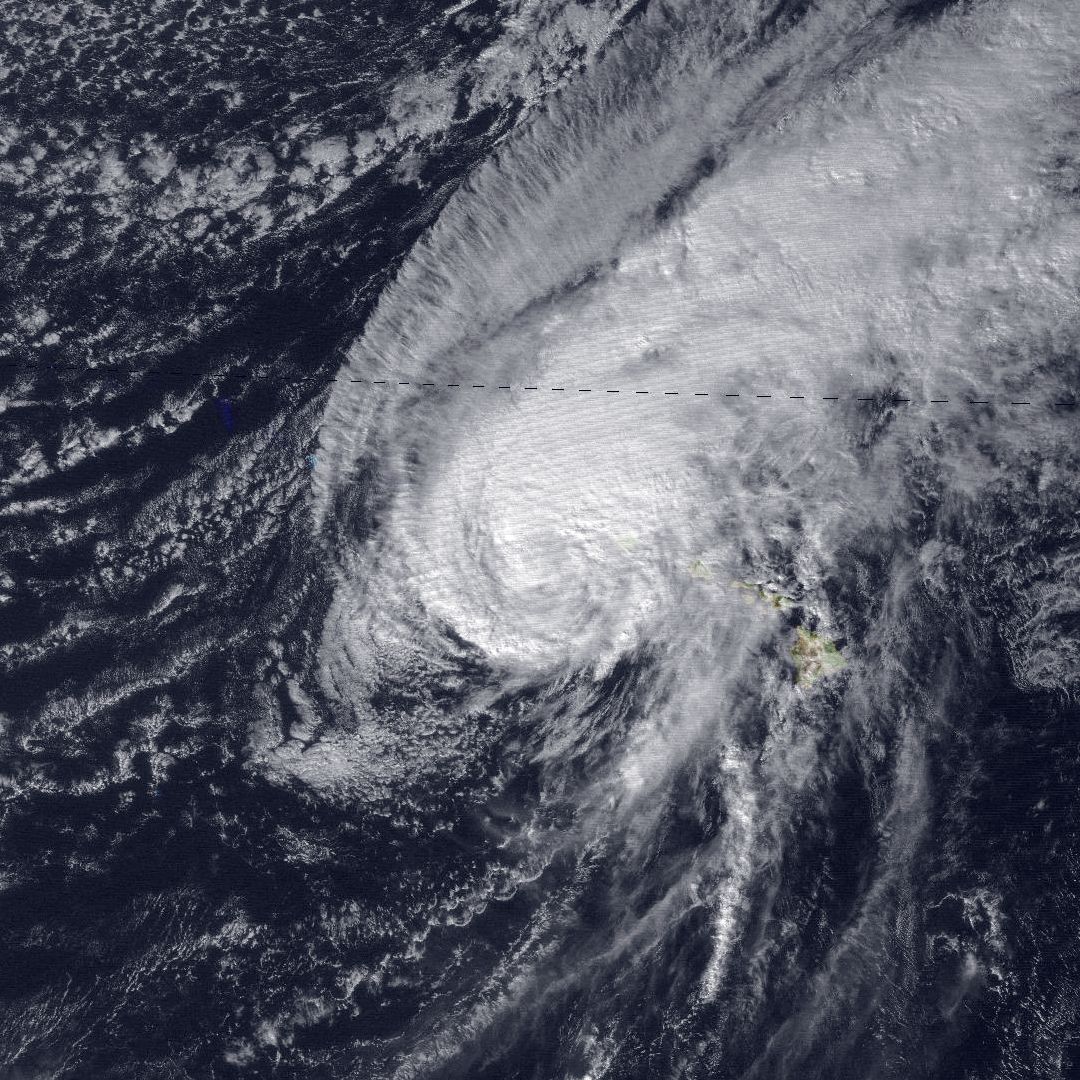

Nov. 25, 1982: Hawaii hurricane

From severe weather and winter storms, we switch to a tropical system. November is still tropical season in the Atlantic and the Pacific, and in Nov. 1982, Hurricane Iwa found its way to Hawaii. It was the first significant hurricane to hit the Hawaiian Islands since the island was made a U.S. state in 1959.

Hurricane Iwa at peak intensity just north of Kauaʻi, Hawaii on Nov. 24, 1982. (NOAA)

The strong Category 1 hurricane with winds of 90 mph struck the islands of Ni’ihau, Kaua’i and O’ahu on Thanksgiving Day 1982. Those areas reported wind gusts of over 100 mph during the storm.

A few gusts up to 120 mph were reported. Coastal locations saw about eight feet of storm surge. In those areas, the ocean waters pushed over 900 feet inland during the surge. One reporting station received over 20 inches of rain during the hurricane.

A clean-up crew picks up tree branches knocked down by Hurricane Iwa. (U.S. National Archives)

Almost 2,000 homes were destroyed. Hundreds were left homeless and four people were killed, either directly or indirectly because of the storm.

Nov. 26-27, 1983: The Great Thanksgiving Weekend Blizzard

In 1983, it was the central and western parts of the country that dealt with a winter storm at Thanksgiving.

The blizzard hit on the Saturday and Sunday after Thanksgiving and affected Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Minnesota, Wyoming and Nebraska.

One of the hardest hit locations was Denver. The city received almost two feet of snow in 36 hours. The storm shut down Stapleton Airport for 24 hours. Several thousand passengers were forced to spend the night at the airport.

It was not much better on the roads around Denver. Thousands of people were stranded on local interstate highways.

Eight to nine-foot snow drifts were reported in Nebraska and Kansas. Major highways were closed in all states affected by the storm.

An interesting fact about the Great Thanksgiving Weekend Blizzard of 1983. Snow from the storm stayed on the ground in Denver for over two months, not melting until late January the following year.

Nov. 26, 1987: Thanksgiving Day Storm

On Thanksgiving Day 1987, a significant winter system hit the northeastern United States.

A winter storm dumped anywhere from 1 to almost two feet of snow from Upstate New York through the New England states. In New Hampshire, parts of the state received 18 inches of snow. In Maine, there were stations that saw just under two feet of snow accumulation.

Along the coast of New Hampshire and Maine, strong winds and waves battered the coastline.

Nov. 23, 1989: Thanksgiving Day Storm

Two years later, another Thanksgiving Day storm battered parts of the East Coast and northeastern U.S.

An unidentified street person huddles with his belongings on the Ellipse morning of Thursday, Nov. 23, 1989 in Washington Monument after a light snow hit the area late Wednesday night. Some 4 inches of snow hit the Washington area on this Thanksgiving Day. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds)

Developing low pressure brought significant rain to the Carolinas and as it moved northward, the system turned more wintry. Parts of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast saw snowfall totals that ranged from a few inches to over a foot.

New York City saw almost 5 inches of snow. Parts of Long Island picked up nine inches of snow. Cape Cod reported over a foot of snow.

An interesting fact about the snow in New York City. Before the snow accumulation on Thanksgiving Day 1989, the last time snow had accumulated there, on Thanksgiving Day, was over 50 years earlier in 1938.

Ryan Tuman, 9, of Erdenheim, N.Y. takes a running belly flop onto the snow-covered bleachers during the Penn-Cornell football game in Philadelphia, Nov. 23, 1989. (AP Photo/Amy Sancetta)

And as bad as the weather was in New York that day, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade went off on schedule. A few of the parade’s big balloons paid the price, however, as they were damaged in the gusty winds caused by the storm.

So overall, thankfully, we’ve been blessed with “not so bad” weather for most Thanksgivings across the United States in the past decades.

So here’s to high pressure and a quiet weather pattern to always be with us around Thanksgiving time. Because we all know, even a little bad weather can go a long way in making a big mess of Thanksgiving plans.

Our team of meteorologists dives deep into the science of weather and breaks down timely weather data and information. To view more weather and climate stories, check out our weather blogs section.