Key points:

Imagine students who understand how government works and who see themselves as vital contributors to their communities. That’s what happens when students are given opportunities to play a role in their school, district, and community. In my work as a teacher librarian, I have learned that even the youngest voices can be powerful, and that students embrace civic responsibility and education when history is taught in a way that’s relevant and meaningful.

Now is the moment to build momentum and move our curriculum forward. It’s time to break past classroom walls and unite schools and communities. As our nation’s 250th anniversary approaches, education leaders have a powerful opportunity to teach through action and experience like never before.

Kids want to matter. When we help them see themselves as part of the world instead of watching it pass by, they learn how to act with purpose. By practicing civic engagement, students gain the skills to contribute solutions–and often offer unique viewpoints that drive real change. In 2023, I took my students [CR1] to the National Mall. They were in awe of how history was represented in stone, how symbolism was not always obvious, and they connected with rangers from the National Park Service as well as visitors in D.C. that day.

When students returned from the Mall, they came back with a question that stuck: “Where are the women?” In 2024, we set out to answer two questions together: “Whose monuments are missing?” and “What is HER name?”

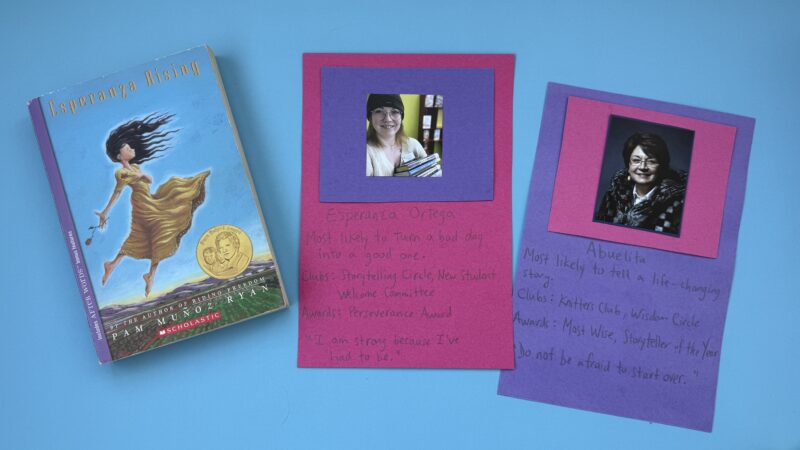

Ranger Jen at the National Mall, with whom I worked with before, introduced me to Dr. Linda Booth Sweeney, author of Monument Maker, which inspired my approach. Her book asks, “History shapes us–how will we shape history?” Motivated by this challenge, students researched key women in U.S. history and designed monuments to honor their contributions.

We partnered with the Women’s Suffrage National Monument, and some students even displayed their work at the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument. Through this project, questions were asked, lessons were learned, and students discovered the power of purpose and voice. By the end of our community-wide celebration, National Mall Night, they were already asking, “What’s next?”

The experience created moments charged with importance and emotion–moments students wanted to revisit and replicate as they continue shaping history themselves.

Reflecting on this journey, I realized I often looked through a narrow lens, focusing only on what was immediately within my school. But the broader community, both local and online, is full of resources that can strengthen relationships, provide materials, and offer strategies, mentors, and experiences that extend far beyond any initial lesson plan.

Seeking partnerships is not a new idea, but it can be easily overlooked or underestimated. I’ve learned that a “no” often really means “not yet” or “not now,” and that persistence can open doors. Ford’s Theatre introduced me to Ranger Jen, who in turn introduced me to Dr. Sweeney and the Trust for the National Mall. When I needed additional resources, the Trust for the National Mall responded, connecting me with the new National Mall Gateway: a new digital platform inspired by America’s 250th that gives all students, educators and visitors access to explore and connect with history and civics through the National Mall.

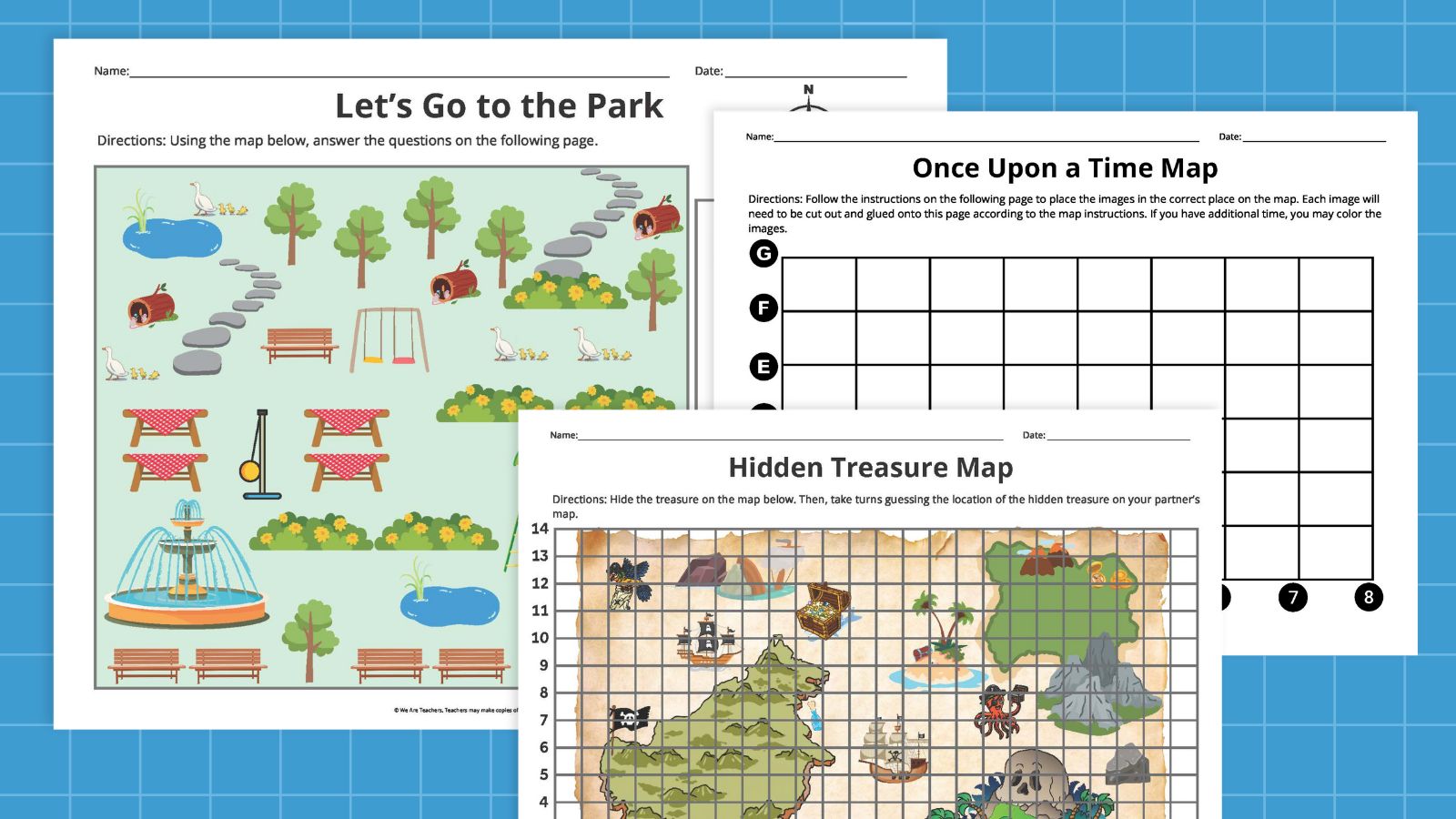

When I first shared the Gateway with students, it took their breath away. They could reconnect with the National Mall–a place they were passionate about–with greater detail and depth. I now use the platform to teach about monuments and memorials, to prepare for field trips, and to debrief afterward. The platform brings value for in-person visits to the National Mall, and for virtual field trips in the classroom, where they can almost reach out and touch the marble and stone of the memorials through 360-degree video tours.

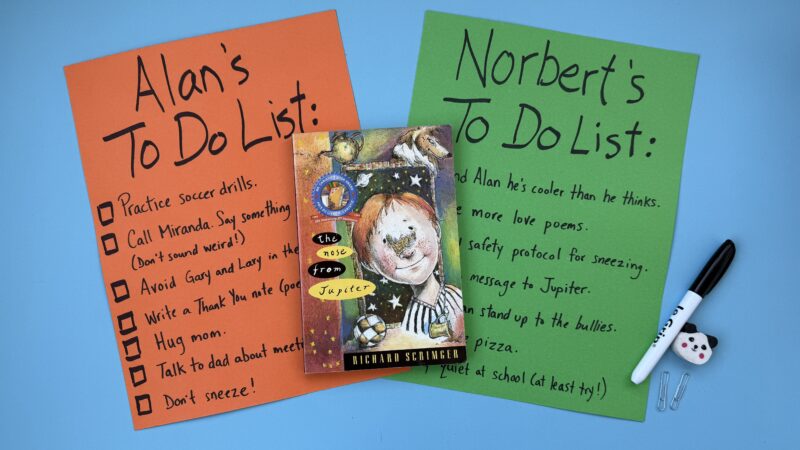

Another way to spark students’ interest in civics and history is to weave civic learning into every subject. The first step is simple but powerful: Give teachers across disciplines the means to integrate civic concepts into their lessons. This might mean collaborating with arts educators and school librarians to design mini-lessons, curate primary sources, or create research challenges that connect past and present. It can also take shape through larger, project-based initiatives that link classroom learning to real-world issues. Science classes might explore the policies behind environmental conservation, while math lessons could analyze community demographics or civic data. In language arts, students might study speeches, letters, or poetry to see how language drives change. When every subject and resource become hubs for civic exploration, students begin to see citizenship as something they live, not just study.

Students thrive when their learning has purpose and connection. They remember lessons tied to meaningful experiences and shared celebrations. For instance, one of our trips to the National Mall happened when our fourth graders were preparing for a Veterans Day program with patriotic music. Ranger Jen helped us take it a step further, building on previous partnerships and connections–she arranged for the students to sing at the World War II Memorial. As they performed “America,” Honor Flights unexpectedly arrived. The students were thrilled to sing in the nation’s capital, of course. But the true impact came from their connection with the veterans who had lived the history they were honoring.

As our nation approaches its 250th anniversary, we have an extraordinary opportunity to help students see themselves as part of the story of America’s past, present, and future.

Encourage educator leaders to consider how experiential civics can bring this milestone to life. Invite students to engage in authentic ways, whether through service-learning projects, policy discussions, or community partnerships that turn civic learning into action. Create spaces in your classes for collaboration, reflection, and application, so that students are shaping history, not just studying it. Give students more than a celebration. Give them a sense of purpose and belonging in the ongoing story of our nation.

Melaney Sánchez, Ph.D., Mt. Harmony Elementary

Source link