[ad_1]

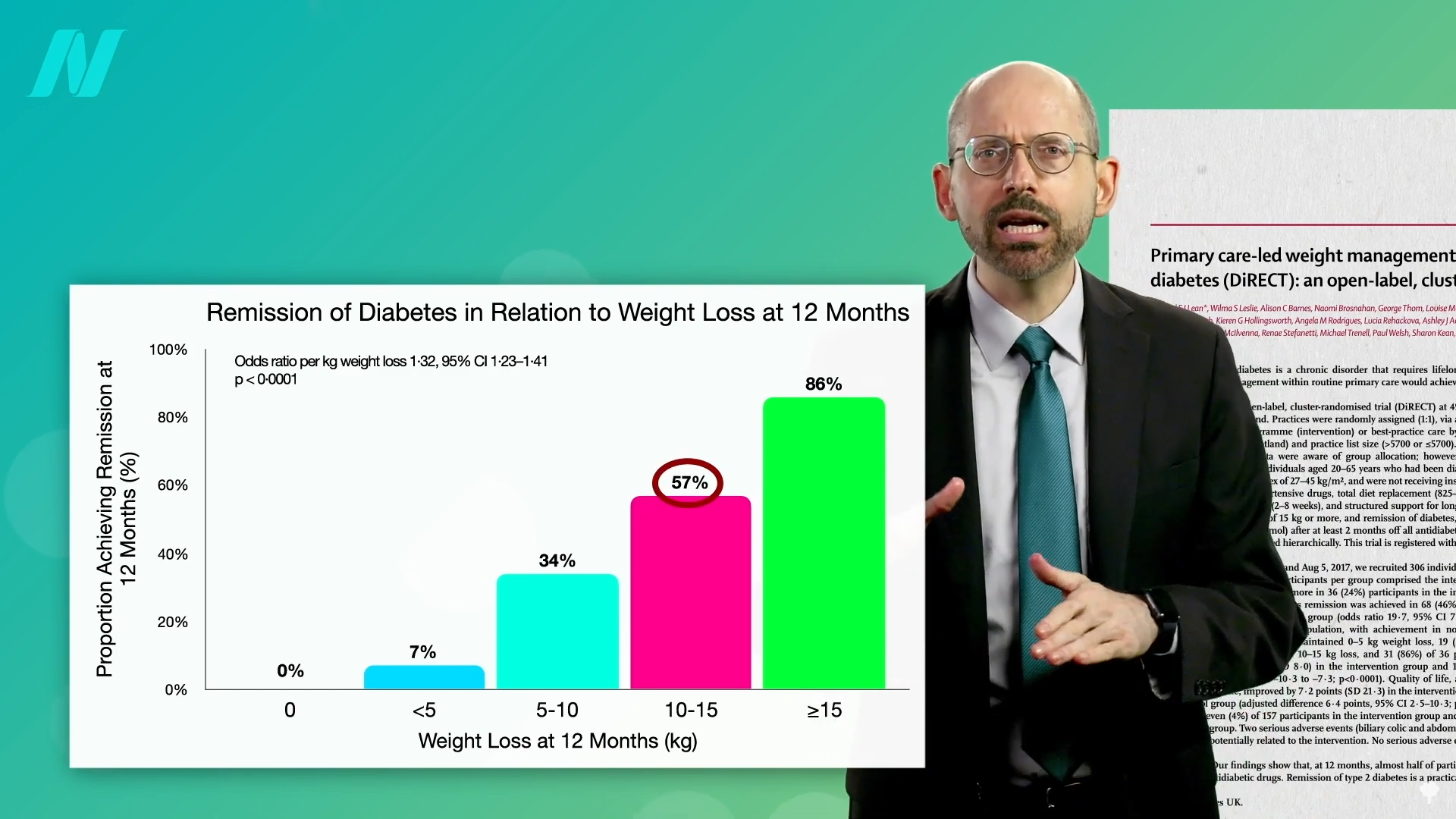

By losing 15% of their body weight, nearly 90% of those who have had type 2 diabetes for less than four years may achieve remission.

Currently, more than half a billion adults have diabetes, and about a 50% increase is expected in another generation. I’ve got tons of videos on the best diets for diabetes, but what about no diet at all?

More than a century ago, fasting was said to cure diabetes, quickly halting its progression and eliminating all signs of the disease within days or weeks. Even so, starvation is guaranteed to lead to the complete disappearance of you if kept up long enough. What’s the point of fasting away the pounds if they’re just going to return as soon as you restart the diet that created them in the first place? Might it be useful to kickstart a healthier diet? Let’s see what the science says.

Type 2 diabetes has long been recognized as a disease of excess, once thought to afflict only “the idle rich…anyone whose environment and self-support does not require of him some sustained vigorous bodily exertion every day, and whose earnings or income permit him, and whose inclination tempts him, to eat regularly more than he needs.” Diabetes is preventable, so might it also be treatable? If we’re dying from overeating, maybe we can be saved by undereating. Remarkably, this idea was proposed about 2,000 years ago in an Ayurvedic text:

“Poor diabetic people’s medicine

He should live like a saint (Munni);

He should walk for 800–900 miles.

Or he shall dig a pond;

Or he shall live only on cow dung and cow urine.”

That reminds me of the Rollo diet for diabetes proposed in 1797, which was composed of rancid meat. That was on top of the ipecac-like drugs he used to induce severe sickness and vomiting. Anything that makes people sick has only “a temporary effect in relieving diabetes” because it reduces the amount of food eaten. His diet plan—which included congealed blood for lunch and spoiled meat for dinner—certainly had that effect.

Similar benefits were seen in people with diabetes during the siege of Paris in the Franco‐Prussian War, leading to the advice to mangez le moins possible, which translates to “eat as little as possible.” This was formalized into the Allen starvation treatment, considered to be “the greatest advance in the treatment of diabetes prior to the discovery of insulin.” Before insulin, there was “The Allen Era.”

Dr. Allen noted that there are clinical reports of even severe diabetes cases clearing up after the onset of a “wasting condition” like tuberculosis or cancer, so he decided to put it to the test. He found that even in the most severe type of diabetes, he could clear sugar from people’s urine within ten days. Of course, that’s the easy part; it’s harder to maintain once they start eating again. To manage patients’ diabetes, he stuck to two principles: Keep them underweight and restrict the fat in their diet. A person with severe diabetes can be symptom-free for days or weeks, but eating butter or olive oil can make the disease come raging back.

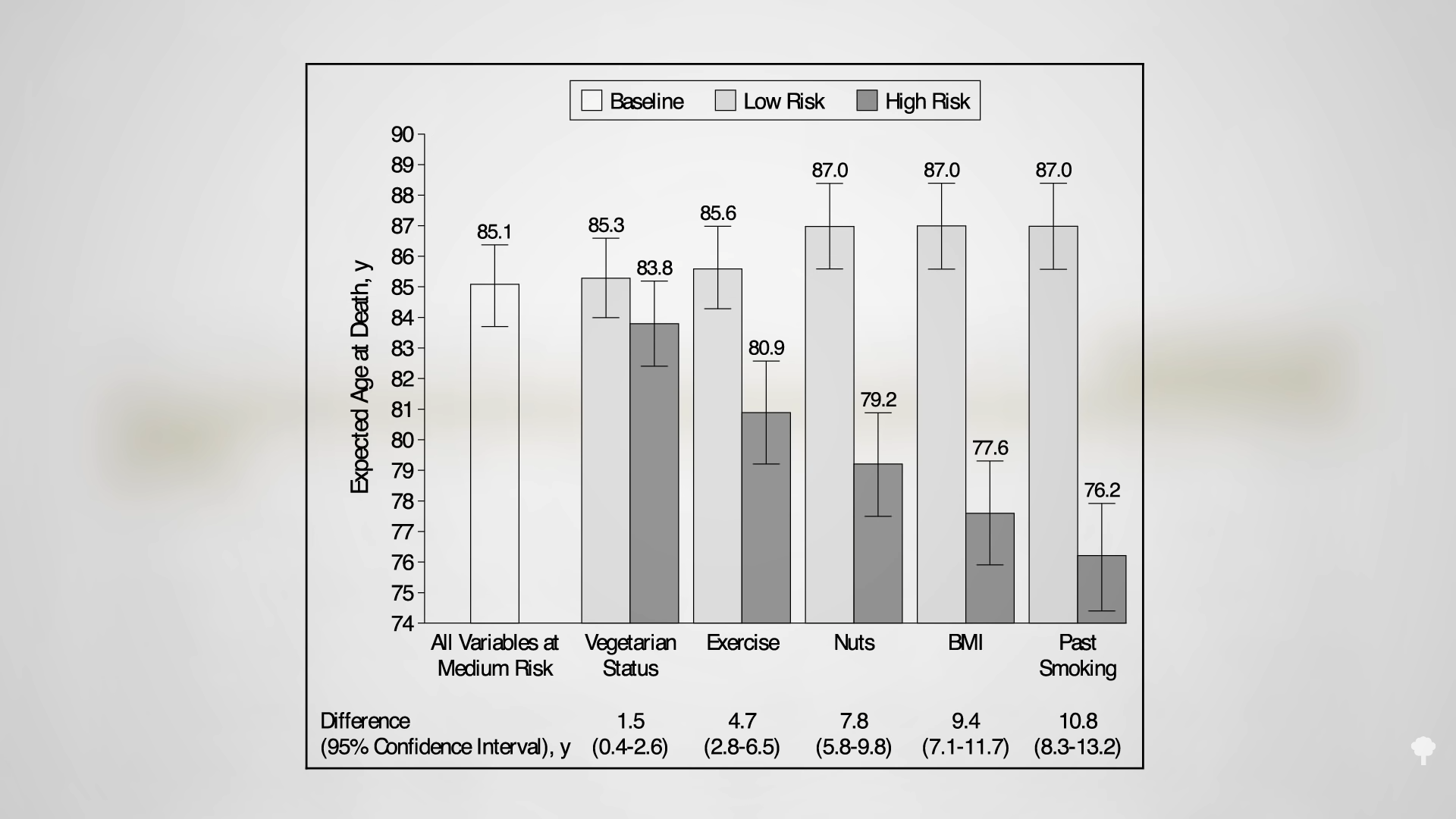

As I’ve said before, diabetes is a disease of fat toxicity. Infuse fat into people’s veins through an IV, and, by using a high-tech type of MRI scanner, you can show in real time the buildup of fat in muscle cells within hours, accompanied by an increase in insulin resistance. The same thing happens when you put people on a high-fat diet for three days. It can even happen in just one day. Even a single meal can increase insulin resistance within six hours. Acute dietary fat intake rapidly increases insulin resistance. Why do we care? Insulin resistance in our muscles, in the context of too many calories, can lead to a buildup of liver fat, followed by fat accumulation in the pancreas, and eventually full-blown diabetes. “Type 2 diabetes can now be understood as a state of excess fat in the liver and pancreas, and remains reversible for at least 10 years in most individuals.”

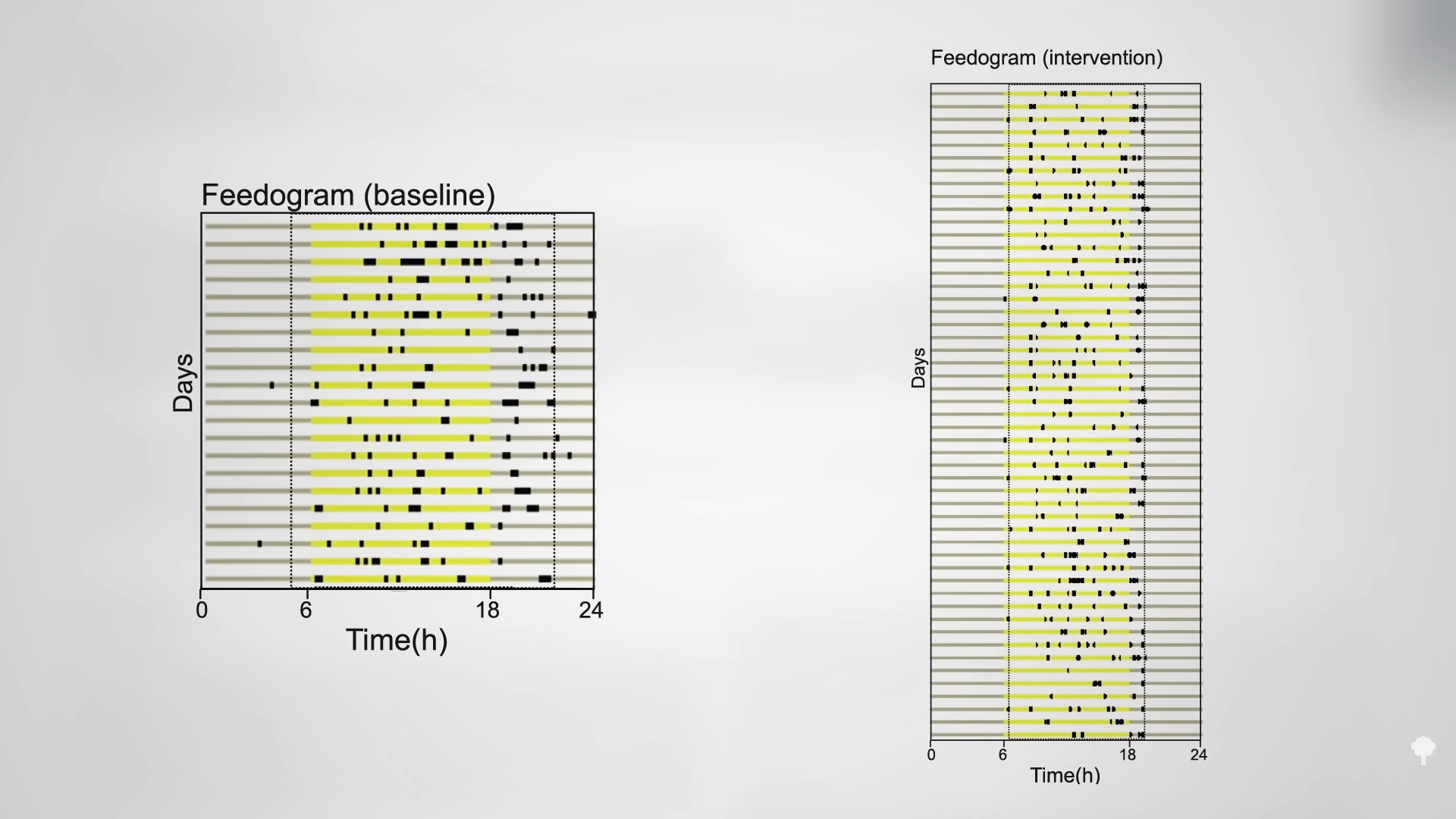

When people are put on a very low-calorie diet—700 calories a day—fat can get pulled out of their muscle cells, accompanied by a corresponding boost in insulin sensitivity, as shown below and at 4:43 in my video Fasting to Reverse Diabetes.

The fat buildup in the liver has then been shown to decrease substantially, and if the diet is continued, the excess fat in the pancreas also reduces. If caught early enough, reversing type 2 diabetes is possible, which would mean sustained healthy blood sugar levels on a healthy diet.

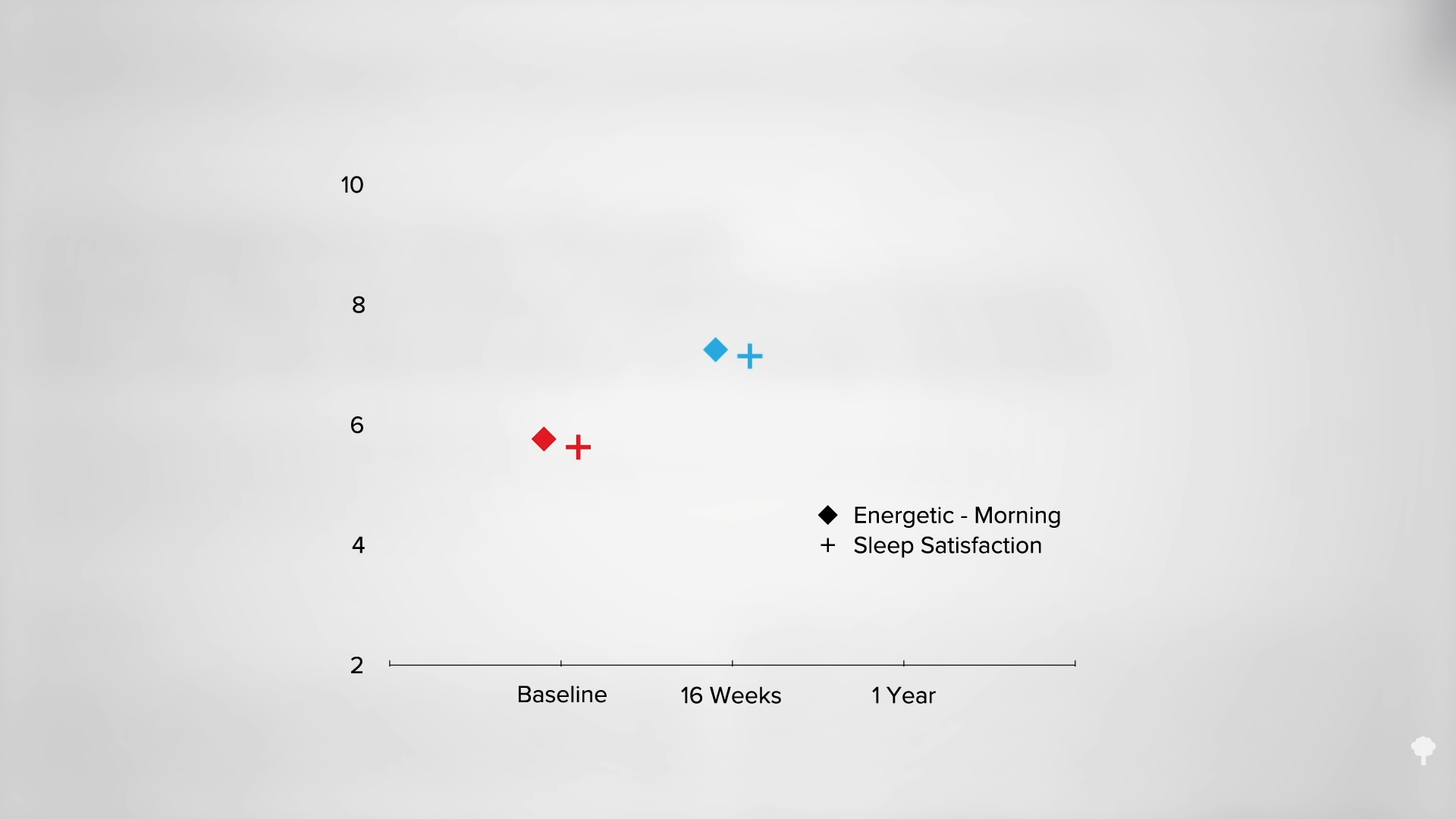

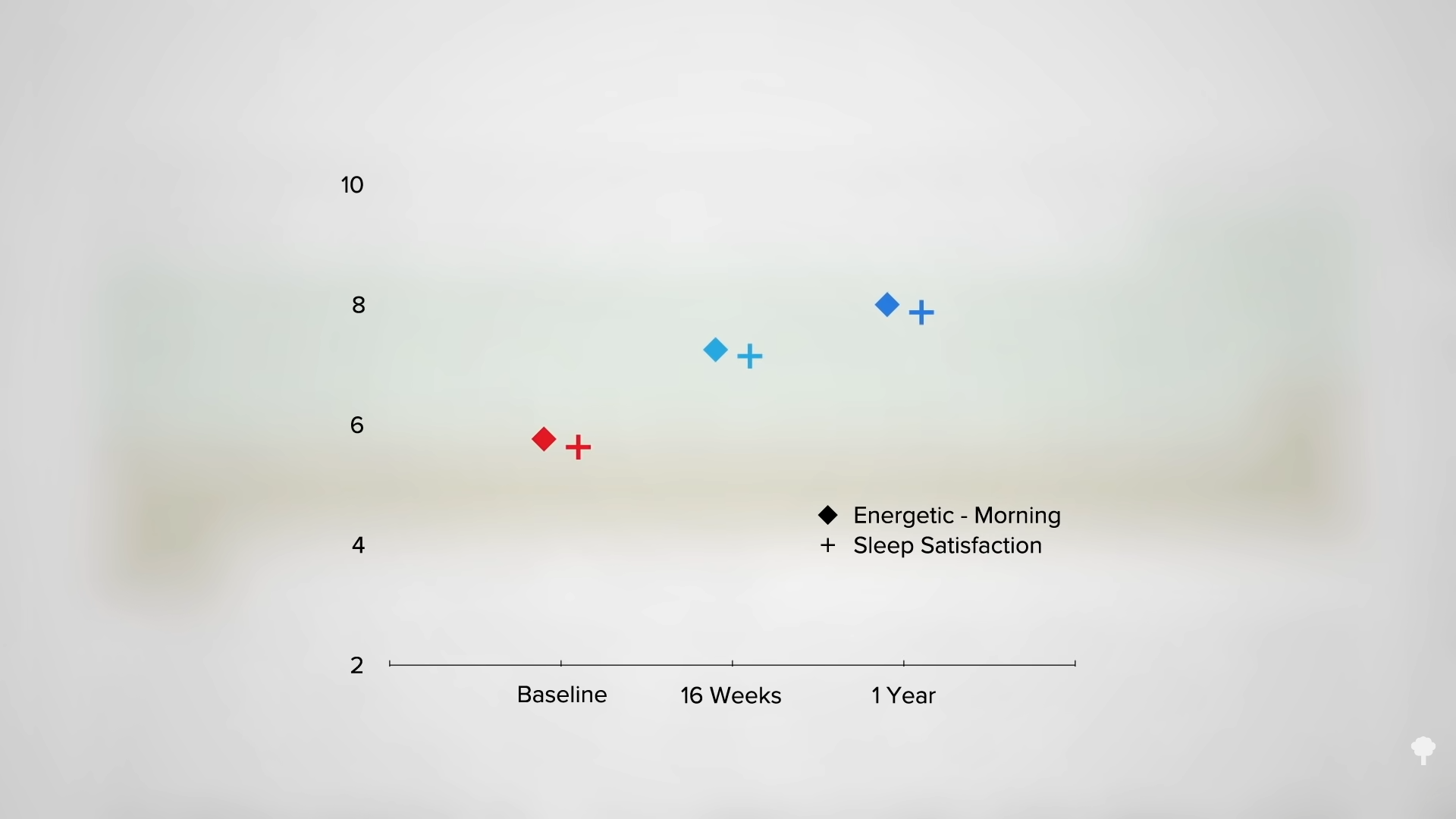

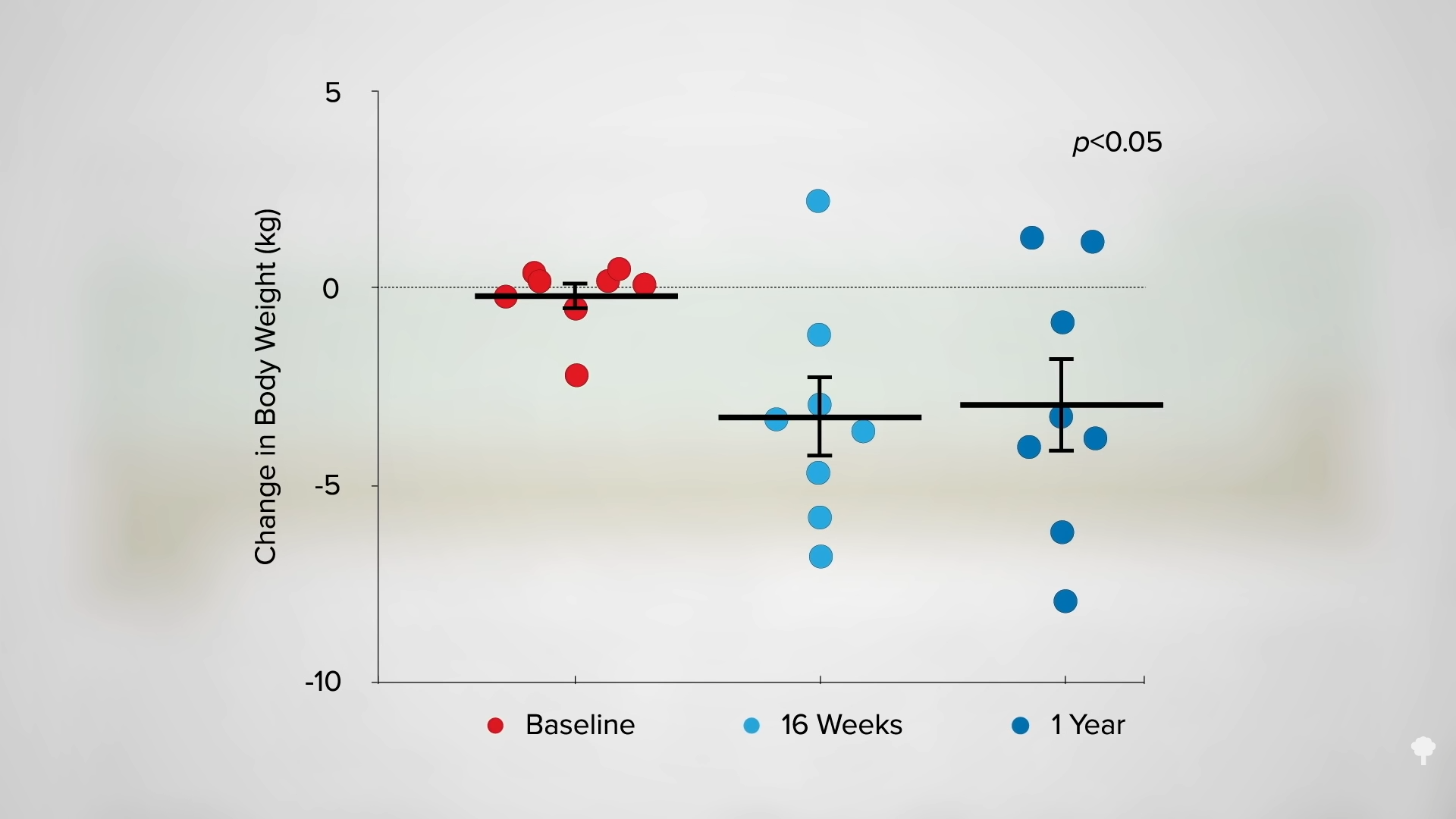

With the loss of 15% of body weight, nearly 90% of individuals who have had type 2 diabetes for less than four years can achieve non-diabetic blood sugar levels, whereas it may only be reversible in 50% of those who’ve lived with the disease for longer than eight years. That’s better than bariatric surgery, where those losing even more weight had lower remission rates of 62% and 26%, respectively. Your forks are better than surgeons’ knives. Indeed, most people who have had their type 2 diabetes diagnosis for an average of three years can reverse their disease after losing about 30 pounds, as you can see below and at 5:37 in my video.

Of course, an extended bout of physician-supervised, water-only fasting could also get you there, but you would have to maintain that weight loss. One of the things that has been said with “certainty” is that if you regain the weight, you regain your diabetes.

To bring it full circle, “the initial euphoria about ‘medicine’s greatest miracle’”—the discovery of insulin in 1921—“soon gave way to the realisation” that, while it was literally life-saving for people with type 1 diabetes, insulin alone wasn’t enough to prevent such complications as blindness, kidney failure, stroke, and amputations in people with type 2 diabetes. That’s why one of the most renowned pioneers in diabetes care, Elliott Joslin, “argued that self-discipline on diet and exercise, as it was in the days prior to the availability of the drug [insulin], should be central to the management of diabetes….”

Doctor’s Note

Check out Diabetes as a Disease of Fat Toxicity for more on the underlying cause of the disease.

For more on fasting for disease reversal, see:

Fasting is not the best way to lose weight. To learn more, see related posts below.

What is the best way to lose weight? See Friday Favorites: The Best Diet for Weight Loss and Disease Prevention.

[ad_2]

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

Source link