KENNEDY SPACE CENTER — During a press conference on Tuesday afternoon, NASA officials said that due to a liquid hydrogen leak and other issues, they will be postponing the crewed Artemis II launch to the moon to no earlier than March.

What You Need To Know

- The liquid hydrogen leak and the bitter cold weather impacted many aspects of the test, NASA stated

- The wet dress rehearsal is a prelaunch test to fuel the rocket; catch any issues and problems before launch

NASA Associate Administrator Amit Kshatriya called the prelaunch test — called the wet dress rehearsal — a “critical milestone.”

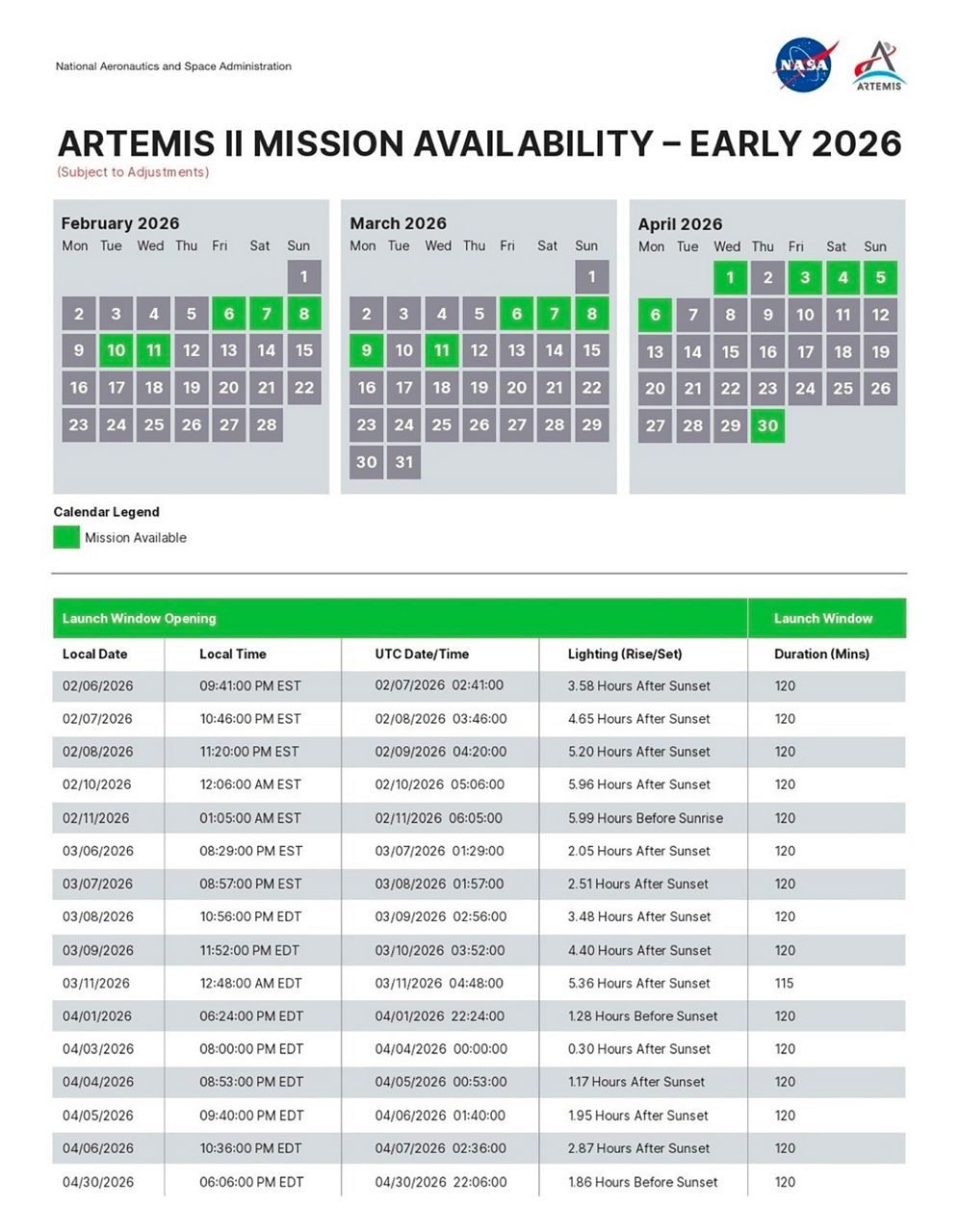

“The wet dress rehearsal we had last night was a critical milestone on the way to Artemis II. That was the reason we went to the pad was to do this test. It allowed our teams to test all the systems required in the in the all up configuration. I think it’s clear based on what we saw in real time, we’re now targeting no earlier than March for Artemis II launch,” he said on Tuesday afternoon.

NASA officials said they will go over all the data and determine how the leaks and issues happened, how to fix them and then determine when the next wet dress rehearsal will be.

During the 49-hour wet dress rehearsal of the Artemis II’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and the Orion capsule that started at 8:13 p.m. ET, Jan. 31, NASA encountered a number of issues.

As NASA was pumping more than 700,000 gallons of cryogenic fuel into the rocket on Monday, engineers discovered a liquid hydrogen leak in an interface that is used to route the fuel into the SLS’s core stage.

A full Moon shines over NASA’s Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft, as it sits atop the mobile launcher in the early hours of Feb. 1, 2026. (NASA/Sam Lott)

This caused the engineers to spend hours troubleshooting the problem, with one solution being to stop the flow of liquid hydrogen and allow the interface to warm up so the seals could reset, then re-adjust the flow of the propellant, NASA explained.

“Teams have stopped the flow of liquid hydrogen through the tail service mast umbilical interface into the core stage after leak concentrations exceeded allowable limits,” the U.S. space agency stated.

That section — interface of the tail service mast umbilical — was the same section where a leak was found during the Artemis I mission.

During the press conference, Artemis II Mission Management Team Chairman John Honeycutt said the team of engineers took a pretty aggressive approach to do testing on the valves and seals and how much they can tolerate, calling the interface where the leak was found “complex.”

“And when you’re dealing with high hydrogen, it’s a small molecule. It’s highly energetic. And we like it for that reason. And we do the best we can. And actually, this one (the leak) caught us off guard. And the initial things that we were seeing and the technical team felt like we either had some sort of misalignment or, or some sort of deformation or, or debris on the seal,” he said.

Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, Artemis II launch director, said that some of the lessons learned during Artemis I were used for this upcoming mission, with some positive results.

“We did make some changes, … but we did make some changes to several of the hydrogen components. I talked about the replenish valve. We had a leak there. We did a design mod. It worked great. We also made some changes. If you remember, from Artemis I, we also had changes in what I would call the back of the plate in the purge can and in the debris plate, we changed the flex hose design that comes into the back of that plate,” she explained.

She said that due to the modifications, the teams did not see any liquid hydrogen leaks where improvements have been made.

With the leaks postponing launches, Spectrum News asked if NASA would consider replacing the SLS rocket and Orion capsule with Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lunar lander for the Artemis III mission, slated for 2027.

“So we are, of course, heavily partnered with Blue Origin and SpaceX and other, you know, super heavy lift launch vehicle providers that are integral to our architecture. So, we’re going to continue to partner with them and share learnings and implement and get them into our to our mission plans. So that’s certainly true. Changing commodity on SLS or changing the design that in that severe way is will probably disable the production significantly. And, you know, make a change. You expect the change. As discussed earlier, it’s hard enough for us to get into a flight-like configuration in a lot of these tests. And so now putting a big design square wave into it, I’m not sure would have the value that we’d expect. What we really want to do is let industry innovate on their own machines. And then when they’re ready to support our missions, we’ll cut them into the architecture and use them as we need to,” Kshatriya answered.

In October 2025, then NASA acting Administrator Sean Duffy said NASA is considering Blue Origin and other companies to handle the task of returning humans to the moon’s surface because SpaceX’s Starship was behind schedule.

Engineers were able to fill all the tanks, both in the core stage and the interim cryogenic propulsion stage.

The wet dress rehearsal allowed NASA to load more than 700,000 gallons of cryogenic propellants into the rocket, conduct a simulated launch countdown, and practice removing propellant from the uncrewed rocket.

However, NASA reported another issue during the simulated countdown.

“Engineers conducted a first run at terminal countdown operations during the test, counting down to approximately 5 minutes left in the countdown, before the ground launch sequencer automatically stopped the countdown due to a spike in the liquid hydrogen leak rate,” the agency stated.

The leak was not the only cause of concern. On the Orion capsule — which will take NASA’s Cmdr. Gregory Reid Wiseman, pilot Victor Glover, mission specialists Christina Koch and Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen to a flyby mission to the moon — a valve associated with the spacecraft’s hatch pressurization needed retorquing, which took longer than planned.

The valve had been replaced before the wet dress rehearsal started.

NASA also stated that the bitterly cold weather that has swept through Florida recently had a hand in plaguing the test. Several cameras and other equipment were impacted by the cold, as well as audio communications dropping out for the ground teams.

All of these issues have forced NASA to look at March for the historic launch.

“With March as the potential launch window, teams will fully review data from the test, mitigate each issue, and return to testing ahead of setting an official target launch date,” NASA stated.

The crew has been released from quarantine, where they have been since Jan. 21 in Houston.

Delays are not uncommon for the Artemis mission, with the first one seeing several of them — liquid hydrogen leaks being one of the main causes.

In fact, Artemis II was supposed to launch in 2025.