SEPTA is moving away from using social media to alert riders about bus and trolley delays, shifting instead to real-time updates on its website, app and third-party platforms like Google Maps.

Molly McVety

Source link

Struggling Santa Clara tech giant gets a big win as rival Nvidia agrees to invest $5 billion in a partnership between both companies to make AI chips for PCs and data centers. Intel stock jumps 23% the next day.

San Francisco supervisor becomes the latest Bay Area politician recalled from office, as Sunset-area voters angry at his support for more housing and turning the Great Highway into a park vote to remove him.

Ian Choudri

Ian ChoudriCalifornia High Speed Rail Authority CEO loses $4 billion after Trump pulls federal funds from the troubled project, but lands $1 billion a year from state lawmakers who extend cap-and-trade program.

Bay Area News Group

Source link

California’s high-speed rail project is slated to receive $1 billion a year in funding through the state’s cap-and-trade program for the next 20 years — a relief to lawmakers who had urged the Legislature to approve the request as billions of dollars in federal funding remain in jeopardy.

State leaders called the move, which is pending a final vote from the Legislature, a necessary step to cementing investments from the private sector — an area of focus for project officials. And the project’s chief executive, Ian Choudri, said the agreement is crucial to completing the current priority — a 171-mile portion from Merced to Bakersfield — by 2033.

“This funding agreement resolves all identified funding gaps for the Early Operating Segment in the Central Valley and opens the door for meaningful public-private engagement with the program,” Choudri said in a statement. “And we must also work toward securing the long-term funding — beyond today’s commitment — that can bring high-speed rail to California’s population centers, where ridership and revenue growth will in turn support future expansions.”

The project was originally proposed with a 2020 completion date, but so far, no segment of the line has been completed. It’s also about $100 billion over the original $33 billion budget that was originally proposed to voters and has received considerable pushback from Republican lawmakers and some Democrats. The Trump administration recently moved to pull $4 billion in funding that was slated for construction in the Central Valley; in turn, the state sued.

Still, advocates of the project believe it’s crucial to the state’s economy and to the nation’s innovation in transit.

“We applaud Governor Newsom and legislative leaders for their commitment and determination to make High-Speed Rail a success,” former U.S. Secretary of Transportation and Co-Chair of U.S. High Speed Rail Ray LaHood said in a statement. “The agreement represents the most important step forward to date for this transformational project.”

State Sen. Dave Cortese (D-San Jose), who chairs the Senate’s Transportation Committee, said the Legislature “must act quickly to pass this plan and keep California on track to deliver America’s first true high-speed rail.”

Construction on the project has been limited to the Central Valley. Choudri has said that the project could take decades to connect the line from Los Angeles to San Francisco and it’s unclear when construction would begin elsewhere in the state. A recent report from the authority proposed next alternatives for the project that would connect the Central Valley to Gilroy and Palmdale. In those scenarios, regional transit would fill in the gaps to San Francisco and Los Angeles.

L.A.-area lawmakers recently requested an annual $3.3-billion investment in transit from the state’s cap-and-trade fund, acknowledging that although high-speed rail is a state priority, L.A. County should not be overlooked when it comes to increasing more immediate transit investments in the state’s most populous county. Citing equity, health and climate needs, the delegation pushed for greater investment in bus, rail and regional connectors.

According to a recent report from the Southern California Assn. of Governments, L.A. County accounts for 82% of Southern California’s bus ridership. Although public transit use is high, lawmakers and transit leaders have said that expansion and improvements are necessary.

“Millions of Los Angeles County residents already depend on Metro bus and rail, Metrolink, and municipal operators. Yet service has not kept pace with need: transit ridership is still 25-30% below pre-pandemic levels, even as freeway traffic has nearly fully rebounded,” the delegation’s letter stated. “Without significant investment, super commuters from the Valley, South LA, and the Inland Empire remain locked into long, expensive car trips.”

Funding commitments for L.A. County transit were maintained from the last budget, but the delegation’s request for billions in cap-and-trade funds has yet to come through.

“The state budget deal in June 2025 restored $1.1 billion in flexible transit funding from the GGRF, which benefits transit operations statewide, including L.A. County,” Sen. Lola Smallwood-Cuevas’ (D-Los Angeles) office said.

Smallwood-Cuevas said the point of the request was to ensure that transit needs of the Los Angeles region aren’t lost.

“We recognize what it means when folks in L.A. County get out of their cars and onto public transit — that is the greatest reduction that can happen,” she said. “We fully intend to see an opportunity where we can address some of that ridership and look at ways to ensure an equitable opportunity that invests in our regional transit public transit, while we also work to build what I call the spine of our transit, a high speed rail program that will run up and down the state and connect to our regional public transit arteries.”

State Sen. Henry Stern (D-Los Angeles) said that the state’s investments toward wildfire recovery in Pacific Palisades and Altadena “does not mean that you should leave the largest segment of drivers anywhere in the world languishing in traffic forever.”

“It’s not that there’d be nothing [for transit funding],” Stern said. “It’s just that we think there should be more.”

The Los Angeles area isn’t facing the same state funding hurdle of the Bay Area, where lawmakers have scrambled to obtain a $750-million transit loan, warning that key services like BART could be significantly affected without the funds.

Roughly $14 billion has been spent on the high-speed rail project so far, which has created roughly 15,000 jobs in the Central Valley. Theoretically, the train will eventually boost economies statewide.

Eli Lipmen of MoveLA believes that the investments will help transit in the Los Angeles region by expanding access, long before there’s a direct high-speed rail connection.

“Wer’e building an incredible transit system with LA Metro, but we need that regional system to get out to Orange County, San Bernardino, Riverside, Ventura County,” Lipmen said.

“So we’re making those investments even if high-speed rail doesn’t come here right away to improve those connections for constituents. That’s a good thing.”

Colleen Shalby

Source link

Amtrak’s NextGen Acela high-speed trains are now racing passengers between Boston, New York and Washington, D.C., hitting top speeds of 160 miles per hour.

Leo Friedman and his mother, Phyllis, traveled from New Jersey to D.C. this week just to take the inaugural train north.

“Ever since that first video came out, that Amtrak posted about nine years ago, I’ve been super interested and invested in this NextGen Acela,” Friedman told CBS News.

Acela was a game-changer when it first launched 25 years ago, doubling Amtrak’s market share in the Northeast.

The 28 new trains will hold about 80 more passengers. They offer upgraded seats, bigger windows, faster Wi-Fi and lots of charging power. All 28 trains, assembled in upstate New York, are expected to be in service by 2027.

There’s also a self-serve food bar in the café car.

Danielle Parhizkaran/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

“This train truly is the future of the high-speed rail in America,” Elliot Hamlisch, Amtrak chief commercial officer, told CBS News. “…This is the most technologically-advanced train, not only in America, but in the world. So we’ve taken the best of what Europe has to offer and incorporated it here on our tracks.”

The new trains have a top speed 10 miles per hour faster than the older Acelas, but still slower than high-speed trains in Europe and Asia. This is in part because of tracks laid over a century ago that wind through communities.

But the new trains are designed to lean into curves, allowing them to go faster.

“This is the next best step to moving us faster in the Eastern Corridor,” Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy told CBS News.

The new Acela trains also meet new, stronger crashworthiness standards, guarding against the kind of jackknife-type derailment that killed eight people and injured more than 200 in Northeast Philadelphia in 2015.

They also come online as the Department of Transportation is pledging $43 million to jumpstart upgrades at New York’s Penn Station. Duffy also announced this week DOT is taking direct oversight of Washington’s Union Station.

The Midwest has relatively good high-speed rail connections compared to the rest of the country, but activists are calling for the region to expand its infrastructure.

The Midwest has been described as a “gateway” for rail connections to the rest of the country because of the railways between Chicago and the East Coast, and proposals for new tracks, particularly in Illinois and Indiana, could double down on that status.

Proponents of high-speed rail see the technology as an economic no-brainer; it’s clean, fast, and provides a huge boom to productivity and access for millions of travelers. However, the infrastructure requires a huge amount of time, money and political capital to build, which is why the few high-speed rail projects that are active in the U.S. have been fraught with funding difficulties and skepticism.

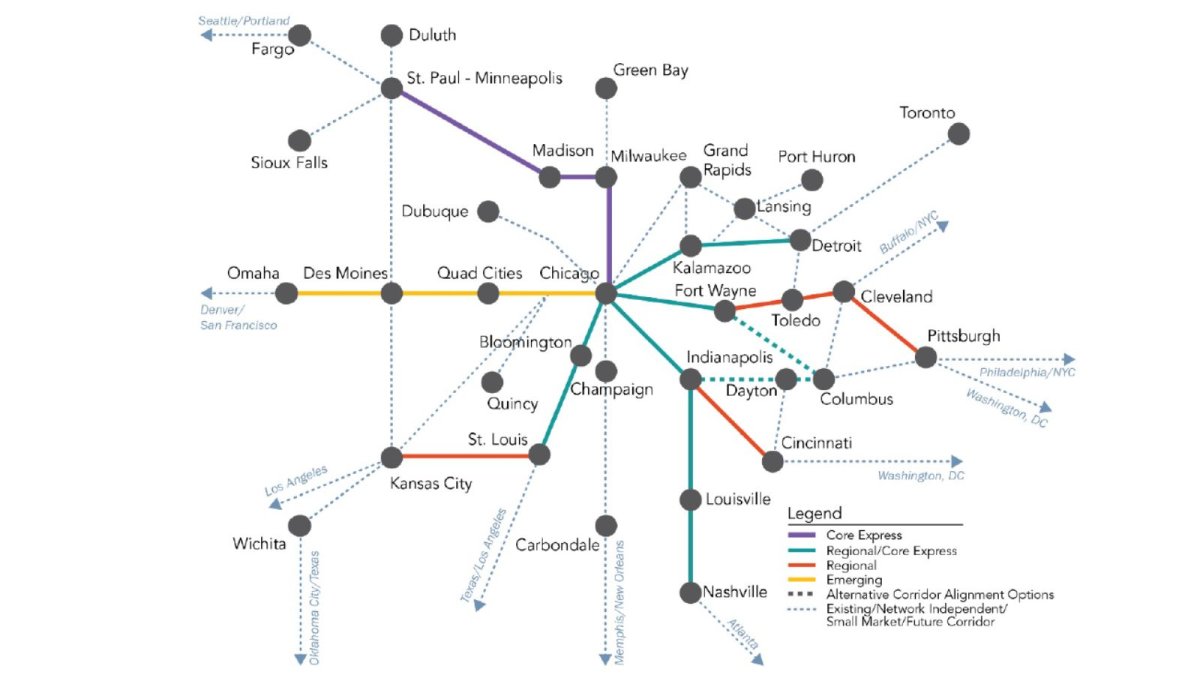

At the core of expansion efforts is the Federal Railroad Administration’s Midwest Regional Rail Plan, which would see the steady expansion of new routes out from Chicago.

The Windy City has long been the regional hub for rail travel, with consistent trains running from Chicago through to New York.

Further, many Amtrak services from states like California and Texas make their way to Chicago rather than directly to New York, making Illinois and the Midwest one of the most important regions for future rail expansion.

The FRA’s plan centers on high-speed “pillar corridors” with endpoints in Chicago, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Detroit, Indianapolis and St. Louis.

These corridors would not only increase capacity on high-traffic routes but also unlock viability for secondary routes, such as Milwaukee to St. Louis or Indianapolis to Minneapolis, that would struggle to justify investment as standalone projects.

The keystone of the network is a new 186-mph line connecting Chicago to Minneapolis-St. Paul via Milwaukee and Madison in Wisconsin. The plan forecasts that nearly 30 percent of all ridership in the region would pass through Chicago, with Minneapolis-St. Paul serving as the second-largest hub at more than 11 percent of projected trips.

If implemented fully, the Midwest rail network could drive ripple effects far beyond its own borders. For example, the Chicago-Indianapolis corridor may lead to future links southward to Louisville, Nashville and eventually Atlanta. This aligns with broader plans under consideration for high-speed rail from Atlanta to Charlotte and Dallas.

The 12 states included in the plan—Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin—represent nearly one-fifth of the U.S. population.

Railway engineer and industry expert Gareth Dennis: “If you have large, long-distance infrastructure or services, then yes, a pan-state or federal organization needs to oversee those. But much of the railroad infrastructure and many services really need to be managed at the state level.

“Of course, people’s movements often cross state boundaries. They travel left, right and center. But if you centralize too much at the federal level, the whole system becomes slow and sluggish. It simply takes too long to respond to challenges. There’s too much decision-making happening at too high a level, where it’s harder to make agile, localized choices about how everything fits together.

The active high-speed rail projects continue to make progress. Their success or failure will likely define how future projects approach scale and financing.

Submit your letter to the editor via this form. Read more Letters to the Editor.

Re: “Bay Area needs unity to solve its problems” (Page A9, Aug. 17).

I second Russell Hancock’s recent call for bold regional leadership in this period of “federal ruckus.” As climate impacts intensify, California must act now to build climate resilience for tomorrow — and for future generations.

Coyote Valley, just south of San José, offers a model for how conservation and stewardship of nature can do that. Here, protected natural and working lands provide a buffer from catastrophic wildfires, floodplains recharge groundwater, wetlands soak up rains to prevent downstream flooding, farmlands grow our food and open space connects over one million acres of critical wildlife corridors. These aren’t just ecological perks. This is essential infrastructure.

Nature-based solutions to climate impacts are cost-effective, scalable and rooted in equity, protecting all communities while enhancing public health and biodiversity.

As Hancock wrote, let’s “put ourselves back in charge.” We can start by investing in the most powerful tool we have: nature.

Andrea Mackenzie

General manager, Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority

San Jose

Re: “Should California’s high-speed rail continue?” (Page A10, Aug. 17).

“Yes! California’s high-speed rail should continue,” is my answer to your question of Aug. 17.

I am a transplant from New England. California had many things of which to be proud. It is never a time to create things of which to be ashamed. All the reasons to attempt this project are still valid. We still need to wean ourselves off intrastate car and plane travel, or at least, provide a good alternative. This is still the environmentally friendly thing to do.

I believe the state must aggressively attempt to remove and mitigate obstacles and unnecessary burdens to the project, to seek greater efficiencies, and continue to fight for federal funding. I also support continued state funding of $1 billion+ a year until the project is complete, even in this time of escalating Trumponomics.

I always want California to be the “Can Do” state.

Bob Greene

Mountain View

Re: “Newsom reveals mapping gambit” (Page A1, Aug. 15).

California’s redistricting (on the Nov. 4 ballot) may be criticized as a “partisan ploy.” However, that ignores the existential threat to our democracy underway by Donald Trump.

The threat is far beyond partisan politics. At stake: whether we’ll have fair elections ever again, in this country.

Trump already attempted a violent coup d’état (after trying other illegal ways to overturn the 2020 election). Upon returning in 2025, he pardoned the convicted felons of Jan. 6, and he has a green light to commit any other crimes, thanks to the Supreme Court that he stacked in his first term.

Now he’s blatantly rigging the 2026 election. What will be left of our democracy by 2028?

Newsom’s proposed redistricting is a necessary, and temporary, antidote to the Trump coup.

Madge Strong

Willits

Re: “Democrats mull a return to state’s gerrymandered past” (Page A6, Aug. 8).

I always thought the term “gerrymandering” came from the 80s when Gov. Jerry Brown started using it in California.

However, consulting with Webster’s dictionary, it came from the early 1800s when Declaration signer Elbridge Gerry was governor of Massachusetts, and later vice president under James Madison. One of the carved-up voting districts he created looked like the head, tail and four legs of a salamander. Another legislator coined the new word, gerrymander, instead.

In any case, gerrymandering is nothing new.

Ron Knapp

Saratoga

The Democratic and Republican parties lack the characteristics needed to work together and to govern our nation effectively. Their inability to lead and cooperate has caused chaos, division and devastation.

Texas and California are taking steps to redraw their congressional districts in an effort to shift power in Congress. As our country’s name clearly implies, the states that make up the United States must be united. The reality is that the states are divided based on the party that controls each state. Ditto the Congress and Senate. As a result, our nation has achieved ill will, division and hostility.

To build unity and foster national peace and harmony, our state and national leaders must end their rivalries and their false belief that anyone from a different political party is the enemy. Our leaders must work together — regardless of party — to govern and unite this country. There is no other way.

Nick Dellaporta

Santa Clara

Every day, the newspaper is crammed with absurdities, making us wonder if we are living in a Franz Kafka novel.

From Donald Trump’s demand for $1 billion from the California taxpayer-supported UCLA to the crackdown on the Smithsonian Museum to the declaration of a public safety emergency in Washington, D.C., after the robbery of a DOGE employee, the list never ends.

It’s normal to feel despair under crazy circumstances. We must, however, be hopeful and do our best to resist. For example, let’s continue to keep ourselves informed, volunteer to help with voter registration and join peaceful rallies. Taking all these actions doesn’t guarantee change, especially in the short run, but if we don’t do anything, things will certainly go from bad to worse.

Florence Chan

Los Altos

Letters To The Editor

Source link

China is eyeing an 8,078-mile high-speed rail line that will directly connect China with the United States. The plan is for the high-speed line to travel from mainland China up through Siberia in Eastern Russia and then under the Bearing Strait into Alaska, across Canada and into the USA. The line would boost tourism and trade between China, Russia, Canada and the United States. The proposed line would be elevated and require an underwater tunnel four times larger than the Channel Tunnel to cross the Bering Strait. With a proposed price tag of $200 billion and increasing geopolitical rivalries amongst the countries that would be involved, this project is purely a wishful dream.

Kyle

Source link

High-Speed rail is finally coming to the United States. The California High-Speed rail authority has received environmental authority to build a high-speed rail connecting downtown Los Angeles with the San Francisco Bay Area. The proposed bullet train will be able to reach speeds of 200 mph and cut travel times between the two metropolitan areas in half. While still slower than bullet trains in China, Japan and other countries, the California line will be the first in pioneering High-Speed rail in the United States.

Kyle

Source link

Once upon a time, way back in 2022, it really looked like Texas Central’s grand plan to construct a 240-mile-long high-speed rail line that would haul passengers from Houston to Dallas in roughly 90 minutes was dead as a doornail.

Sure, the Texas Supreme Court had awarded the company the right to use eminent domain to get the project built – a crucial win since landowners in between the two cities have been battling the project for years now. But a day later the company’s CEO resigned, and it soon leaked out that the board had dissolved itself weeks beforehand.

After more than a decade of effort, it really looked like the grand plan to see the famed Japanese Shinkansen trains zipping between two of the state’s largest cities had come to nothing.

Or at least that’s what everyone thought until Amtrak – and Andy Byford, the Amtrak leader in charge of high speed rail — got involved.

🚄 America’s high-speed rail era is here! We operate America’s fastest train (Acela up to 150 mph) and see big potential for HSR beyond the Northeast.

Discover why we believe Dallas ↔️ Houston is a prime candidate for HSR, from Amtrak President Roger Harris and SVP Andy Byford. pic.twitter.com/4zoOe96p8p

— Amtrak (@Amtrak) April 29, 2024

Byford — who was dubbed “Train Daddy” by New Yorkers when he was running, and rapidly improving, the city’s beleaguered subway system — climbed aboard Amtrak back in March 2023 focused on making high speed rail a reality in more of the country. He quickly zeroed in on the Houston-to-Dallas project.

Why? “You’ve got to have the right characteristics,” Byford said in the video, ticking off how you need cities with large populations a good distance apart from each other, limited stops, few curves in the route and fairly smooth topography. “The one that stands out – and to be fair it was already being looked at when I got here but we’ve taken it to the next level – and that’s Dallas and Houston.”

Thus, last August Amtrak threw Texas Central a lifeline. The duo announced, via press release, they were exploring partnering up to examine finally making the Shinkansen rail line a reality. The partnership with the quasi-public corporation that oversees American passenger rail quickly produced results. By December, Amtrak was awarded a $500,000 federal grant to further study the project.

Since then, as Byford stated at the Southwestern Rail Conference in Hurst, Texas last month, Amtrak and Texas Central have signed a nonbinding agreement to further explore the project. Amtrak officials have been doing their due diligence about the actual state of the project.

Meanwhile, it’s clear that the Biden Administration is backing the plan. (Not exactly a shock considering President Joe Biden’s famed love of trains and long history with Amtrak.)

“We believe in this,” U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg said of the project while appearing on the DFW-based Sunday morning show, Lone Star Politics, in early April. “Obviously it has to turn into a more specific design and vision but everything I’ve seen makes me very excited about this.”

The following week, Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida issued a fact sheet voicing both governments’ support for the project during Kishida’s state visit. “The successful completion of development efforts and other requirements would position the project for potential future funding and financing opportunities,” the White House said, while both countries’ transportation departments hailed Amtrak getting involved with the project.

However, this isn’t a done deal. Amtrak plans to spend another 18 months examining the project – and the hurdles that still need to be jumped, including getting Japan’s Shinkansen technology approved and obtaining federal environmental approval. Only then will Amtrak actually make a call about the project.

On top of that, although Texas Central had secured about 30 percent of the required land by 2022, there’s still the other 70 percent to go, while Texans Against High Speed Rail, the nonprofit organization of mostly rural landowners who to oppose the project, is still decidedly against it, warning that “there is still a lot for the Biden Administration to understand” about it before committing to getting it built.

In other words, Amtrak hasn’t magically whisked away every issue the bullet train was facing before it got involved. But, at the same time, now that Amtrak and “Train Daddy” Byford are in the mix who knows what might happen or how far this bullet train plan may go.

Dianna Wray

Source link

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

Ground was broken today on what is said to be America’s first high-speed rail. The project, which is designed to connect Los Angeles and Las Vegas via a 218-mile stretch of track that will be built across the Mojave desert, will be completed within the next four years, its backers say.

The proposed infrastructure project will stretch from the California city of Rancho Cucamonga to Vegas and is being headed by rail construction firm Brightline. In its description of the project, the company notes that the new route will be traveled by “all-electric, zero-emission trains” that will be capable of “reaching top speeds of 200 mph, getting passengers from Las Vegas to Rancho Cucamonga in about 2 hours and 10 minutes (2x faster than the normal drive time).” The project was helped along by $3 billion in federal funding supplied by the Biden administration, the Associated Press writes.

In a press release from Biden Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, the government said the project would “remove an estimated 400,000 tons of carbon dioxide per year, bolster tourism, and create 35,000 good-paying jobs.”

“As the first true high-speed rail system in America, Brightline West will serve as the blueprint for connecting cities with fast, eco-friendly passenger rail throughout the country,” Brightline’s Founder and Chairman Wes Edens, previously said. “Connecting Las Vegas and Southern California will provide wide-spread public benefits to both states, creating thousands of jobs and jumpstarting a new level of economic competitiveness for the region. We appreciate the confidence placed in us by DOT and are ready to get to work.”

The AP also notes that Brightline already operates a railway system between Miami and Orlando in Florida. Gizmodo reached out to the company for details about its new project and will update this story if it responds.

Many countries around the world have modernized their rail systems. Much of Europe is connected by a bevy of efficient and comfortable train systems, while Japan’s bullet trains have long been a source of pride for the country. China is said to have the fastest trains in the world and it has built up a highly effective high-speed rail network in a period of just twenty years. The U.S., meanwhile, has largely failed to develop any sort of modernized rail travel, despite decades of talk about the benefits that such systems could bring to Americans.

One can only hope that this new effort won’t suffer the same fate as California’s long-suffering attempt to erect a high-speed rail service between Los Angeles and San Francisco. That project, which was originally approved by state voters in 2008, has—as of this year—completed less than a quarter of the proposed rail line and is currently missing billions of dollars in funding. In March, project leaders told California lawmakers that the full rail line that had originally been envisioned would need another $100 billion and years to complete.

Lucas Ropek

Source link

Gov. Gavin Newsom got the Christmas present he desperately wanted from President Biden: the crucial piece of a train set.

It’s a relatively small piece that’s vital to eventually making this fancy electric train work.

I’m referring to the much-maligned bullet train that three California governors have been trying to build .

When complete, it will carry passengers from Los Angeles to San Francisco in less than three hours at speeds of up to 220 mph. That’s the sales pitch, anyway.

Biden’s gift is a $3.1-billion grant that’s badly needed to continue work on the high-speed rail line’s initial segment in the San Joaquin Valley.

The ambitious project has been widely lampooned over the years by many, including me, as a too-costly boondoggle and off track from the start.

But let’s get real: This giant adult toy is going to be constructed one way or another, whether at reasonable speed or in pokey chug-chug fashion. It’s time we acknowledge that and focus on making it work the best for everyone. And sooner the better.

You don’t spend $11 billion on a project, as California already has, then abandon it.

Critics consistently have asserted that bullet train money should be shifted to more essential projects — reducing homelessness, educating kids, widening freeways. But that’s practically impossible. Most bullet train money — state bonds and federal grants — can be used only for high-speed rail.

Ardent supporters just as erroneously constantly point out that California is the world’s fifth-largest economy. And if nations with smaller economies — in Europe and Asia — can afford bullet trains, they argue, California certainly can.

Wrong. Those are nations, not states. They heavily subsidize high-speed rail and can do that because their purse strings are much looser. States have budget-balancing requirements. And they can’t print money.

It would be politically impossible for California alone to finance the Los Angeles-to-San Francisco high-speed rail line that’s currently projected to cost a gargantuan $110 billion. And that estimate keeps growing. It’s now roughly three times what voters were told the line would cost when they approved a nearly $10-billion bond issue for the bullet train in 2008.

“The longer it takes to build, the more expensive it is,” says Brian Kelly, chief executive officer of the California High-Speed Rail Authority.

“But it’s a lot cheaper than expanding freeways and airports.”

Could the work already done be converted to use by conventional, non-electrified passenger trains? That would be a lot less expensive.

“I suppose so,” Kelly says. “But to continue to run yesterday’s technology would not be in the state’s interest. It would be a disaster.”

The appeal of electrified trains — besides their zippy speed — is that they burn clean energy, not climate-warming fossil fuels.

But like bullet trains in Europe and Asia, California’s need generous federal funding — lots of it.

Several years ago, the feds gave California $3.5 billion for the project. That’s long gone. And it’s all the money Washington has sent — in no small part because former Republican House Speaker Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield hated the bullet train because its tracks cut through his constituents’ farm fields.

But now, Biden’s Christmas present to Newsom will allow him to continue erecting the project’s first 171-mile segment from Merced to Bakersfield. The line is supposed to be operational by 2030.

“The train to nowhere,” critics long have cried.

“That’s wrong and offensive,” Newsom responded in his first State of the State Address in 2019. “The people of the Central Valley … deserve better.”

A 2022 poll by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies found wide public support for continuing to build the rail line regardless of whether it initially operates only in farm country. Among registered voters, 56% favored it, with 35% opposed.

But there was a huge partisan difference: 73% of Democrats favored construction and 66% of Republicans were opposed.

Newsom said the federal gift amounts to “a vote of confidence … and comes at a critical turning point, providing the project new momentum.”

OK, but the question still remains: Why would anyone bother to take a bullet train from Merced to Bakersfield?

Kelly answers that Amtrak already draws 1.5 million passengers annually in the valley. And high-speed rail is projected to attract 7 million.

The next links will be into the San Francisco Bay Area by 2033 — it’s promised — and later into Los Angeles and Anaheim. No one has a clue when the entire line will be complete.

The total projected cost of just the San Joaquin Valley line is up to $32 billion. That money is far from lined up.

Kelly’s goal is to get an additional $5 billion from the same kitty that provided the Christmas gift: the $1.2-trillion infrastructure package that Biden pushed through Congress and signed in 2021.

Newsom’s rail project simultaneously got a second boost from the Biden administration — indirectly, at least — when it approved a $3-billion grant for a planned bullet train between Las Vegas and Southern California.

Kelly intends to connect California’s bullet train to the Vegas line and make it easier for Central Valley residents to travel by rail to Sin City.

“This is a great opportunity for high-speed rail — to buy trains together and be more efficient,” Kelly says.

But California’s electric train remains tens of billions of dollars short of enough money for completion — with no additional dollars in sight.

Private investors haven’t shown any interest. It’s doubtful California taxpayers would dig deeper. Washington is where the money is. How does Sacramento keep tapping into its vaults?

“What they really want to see is people working,” Kelly says. “We’ve got to keep grinding, keep advancing.”

If Newsom’s a good boy, maybe Washington’s Santa will give him another piece of the train set next Christmas.

George Skelton

Source link

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

A high-speed rail project between the Inland Empire and Las Vegas landed a $3-billion federal grant that sets it on track to be open by 2028, in time for the Olympic Games in Los Angeles, officials said Tuesday.

Brightline, a private company that opened an intercity rail line connecting Miami and Orlando, Fla., this year, secured the U.S. Department of Transportation grant as part of the historic infrastructure package, Nevada‘s U.S. senators said. The rest of the funds for the $12-billion project are expected to be raised through private capital and bonds.

The trip on the 218-mile electrified line from Rancho Cucamonga to Las Vegas will take just over two hours, with stops in Hesperia or Apple Valley, according to Brightline. The trains can reach speeds of 200 miles per hour. The company already has the federal permits, the labor agreements and the land — a swath in the wide median of Interstate 15 — to build the line. Construction is expected to begin early next year.

In Southern California the line will connect to the Metrolink commuter train system, linking it directly to downtown Los Angeles. In Las Vegas, the terminus will be on the south end of Las Vegas Boulevard.

The company operates the only high-speed private rail service in the United States and its rapid rise runs in stark contrast to California’s effort to build a high-speed rail between Los Angeles and the Bay Area, which has been mired by politics, cost overruns and delays.

California submitted a separate $3-billion high- speed rail application that Gov. Newsom said in a letter to the White House would allow the state to complete an initial 119-mile segment in the Central Valley. Federal officials have not made any announcements on that project.

The Brightline grant application was co-submitted with the Nevada Department of Transportation.

“This is a historic moment that will serve as a foundation for a new industry, and a remarkable project that will serve as the blueprint for how we can repeat this model throughout the country,” said Wes Edens, founder and chairman of Brightline. “We’re ready to get to work to bring our vision of American-made, American-built, world class, state-of-the-art high-speed train travel to America.”

Although Brightline did not get the full $3.7-billion package that it hoped for, the grant will ensure the project’s construction, officials said. The train is conceived as both a premium tourist train and a more traditional transportation link between Southern California and Las Vegas, two regions with deep ties. The company has said that passengers may ultimately be able to check into their Las Vegas hotels at the train station.

“This historic high-speed rail project will be a game changer for Nevada’s tourism economy and transportation,” said Sen. Jacky Rosen (D-Nev). “It’ll bring more visitors to our state, reduce traffic on the I-15, create thousands of good-paying jobs and decrease carbon emissions, all while relying on local union labor.”

Rachel Uranga

Source link

CNN

—

Indonesia is launching Southeast Asia’s first-ever bullet train on Sunday, a high-speed rail service line that will connect two of the country’s largest cities.

Part of China’s Belt and Road infrastructure initiative and largely funded by Chinese state-owned firms, the $7.3 billion project opened to the public on Sunday, following a series of delays and setbacks.

The train will travel between the capital Jakarta and Bandung in West Java, Indonesia’s second-largest city and a major arts and culture hub.

The 86-mile (138-kilometer) high-speed rail line, officially named WHOOSH – which stands for “time saving, optimal operation, reliable system” in Indonesian – runs on electricity with no direct carbon emissions and travels at a speed of roughly 217 miles per hour – cutting travel time between Jakarta and Bandung from three hours to under less than an hour, officials say.

Overseen by the joint state venture PT Kereta Cepat Indonesia China (PT KCIC), the train travels between the Halim railway station in East Jakarta and Padalarang railway station in West Bandung, and is well connected to local public transport systems.

The trains, modified for Indonesia’s tropical climate, are equipped with a safety system that can respond to earthquakes, floods and other emergency conditions, officials added.

There are talks to extend the high-speed line to Surabaya – a major port and capital of East Java Province, PT KCIC director Dwiyana Slamet Riyadi told Chinese state media outlets at a ceremony earlier in September.

Stops at other major cities like Semarang and Yogyakarta, the gateway to Borobudur – the largest Buddhist temple in the world – are also being planned, Dwiyana said.

According to information released by PT KCIC, the railway features eight cars – all equipped with Wi-Fi and USB charging points – and seats 601 passengers.

There will be three classes of seats – first, second and VIP.

Indonesia, the world’s fourth-largest country and Southeast Asia’s largest economy, has been actively and openly courting investment from China, its largest trade and investment partner.

A high-profile meeting in July between Indonesian and Chinese leaders Joko Widodo and Xi Jinping unveiled a series of projects, including plans to build a multi-billion dollar Chinese glass factory on the island of Rempang in Indonesia’s Riau Islands Archipelago as part of a new ‘Eco-City,’ sparking weeks of fierce protests from indigenous islanders opposed to their villages being torn down.

Widodo and Chinese Premier Li Qiang were photographed taking test rides on the new high-speed railway throughout September.

The train deal was first signed in 2015 as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and construction began later that year.

It was initially expected to be completed in 2019 but has faced multiple operational delays as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic as well as land procurement and ballooning costs.

PT KCIC’s director Dwiyana hailed the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway as an “outstanding example of bilateral cooperation between Indonesia and China.” It will not only improve Indonesian infrastructure but “promote the development of Indonesia’s railroad and manufacturing industries,” he said.

CNN

—

High speed trains have proved their worth across the world over the past 50 years.

It’s not just in reducing journey times, but more importantly, it’s in driving economic growth, creating jobs and bringing communities closer together. China, Japan and Europe lead the way.

So why doesn’t the United States have a high-speed rail network like those?

For the richest and most economically successful nation on the planet, with an increasingly urbanized population of more than 300 million, it’s a position that is becoming more difficult to justify.

Although Japan started the trend with its Shinkansen “Bullet Trains” in 1964, it was the advent of France’s TGV in the early 1980s that really kick-started a global high-speed train revolution that continues to gather pace.

But it’s a revolution that has so far bypassed the United States. Americans are still almost entirely reliant on congested highways or the headache-inducing stress of an airport and airline network prone to meltdowns.

China has built around 26,000 miles (42,000 kilometers) of dedicated high-speed railways since 2008 and plans to top 43,000 miles (70,000 kilometers) by 2035.

Meanwhile, the United States has just 375 route-miles of track cleared for operation at more than 100 mph.

“Many Americans have no concept of high-speed rail and fail to see its value. They are hopelessly stuck with a highway and airline mindset,” says William C. Vantuono, editor-in-chief of Railway Age, North America’s oldest railroad industry publication.

Cars and airliners have dominated long-distance travel in the United States since the 1950s, rapidly usurping a network of luxurious passenger trains with evocative names such as “The Empire Builder,” “Super Chief” and “Silver Comet.”

Deserted by Hollywood movie stars and business travelers, famous railroads such as the New York Central were largely bankrupt by the early 1970s, handing over their loss-making trains to Amtrak, the national passenger train operator founded in 1971.

In the decades since that traumatic retrenchment, US freight railroads have largely flourished. Passenger rail seems to have been a very low priority for US lawmakers.

Powerful airline, oil and auto industry lobbies in Washington have spent millions maintaining that superiority, but their position is weakening in the face of environmental concerns and worsening congestion.

US President Joe Biden’s $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill includes an unprecedented $170 billion for improving railroads.

Some of this will be invested in repairing Amtrak’s crumbling Northeast Corridor (NEC) linking Boston, New York and Washington.

There are also big plans to bring passenger trains back to many more cities across the nation – providing fast, sustainable travel to cities and regions that have not seen a passenger train for decades.

Add to this the success of the privately funded Brightline operation in Florida, which has been given the green light to build a $10 billion high-speed rail link between Los Angeles and Las Vegas by 2027, plus schemes in California, Texas and the proposed Cascadia route linking Portland, Oregon, with Seattle and Vancouver, and the United States at last appears to be on the cusp of a passenger rail revolution.

“Every president since Ronald Reagan has talked about the pressing need to improve infrastructure across the USA, but they’ve always had other, bigger priorities to deal with,” says Scott Sherin, chief commercial officer of train builder Alstom’s US division.

“But now there’s a huge impetus to get things moving – it’s a time of optimism. If we build it, they will come. As an industry, we’re maturing, and we’re ready to take the next step. It’s time to focus on passenger rail.”

Sherin points out that other public services such as highways and airports are “massively subsidized,” so there shouldn’t be an issue with doing the same for rail.

“We need to do a better job of articulating the benefits of high-speed rail – high-quality jobs, economic stimulus, better connectivity than airlines – and that will help us to build bipartisan support,” he adds. “High-speed rail is not the solution for everything, but it has its place.”

Only Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor has trains that can travel at speeds approaching those of the 300 kilometers per hour (186 mph) TGV and Shinkansen.

Even here, Amtrak Acela trains currently max out at 150 mph – and only in short bursts. Maximum speeds elsewhere are closer to 100 mph on congested tracks shared with commuter and freight trains.

This year, Amtrak plans to introduce its new generation Avelia Liberty trains to replace the life-expired Acelas on the NEC.

Capable of reaching 220 mph (although they’ll be limited to 160 mph on the NEC), the trains will bring Alstom’s latest high-speed rail technology to North America.

The locomotives at each end – known as power cars – are close relatives of the next generation TGV-M trains, scheduled to debut in France in 2024.

Sitting between the power cars are the passenger vehicles, which use Alstom’s Tiltronix technology to run faster through curves by tilting their bodies, much like a MotoGP rider does. And it’s not just travelers who will benefit.

“When Amtrak awarded the contract to Alstom in 2015 to 2016, the company had around 200 employees in Hornell,” says Shawn D. Hogan, former mayor of the city of Hornell in New York state.

“That figure is now nearer 900, with hiring continuing at a fast pace. I calculate that there has been a total public/private investment of more than $269 million in our city since 2016, including a new hotel, a state-of-the-art hospital and housing developments.

“It is a transformative economic development project that is basically unheard of in rural America and if it can happen here, it can happen throughout the United States.”

Alstom has spent almost $600 million on building a US supply chain for its high-speed trains – more than 80% of the train is made in the United States, with 170 suppliers across 27 states.

“High-speed rail is already here. Avelia Liberty was designed jointly with our European colleagues, so we have what we need for ‘TGV-USA’,” adds Sherin.

“It’s all proven tech from existing trains. We’re ready to go when the infrastructure arrives.”

And those new lines could arrive sooner than you might think.

In March, Brightline confirmed plans to begin construction on a 218-mile (351-kilometer) high-speed line between Rancho Cucamonga, near Los Angeles, and Las Vegas, carving a path through the San Bernardino Mountains and across the desert, following the Interstate 15 corridor.

The 200 mph line will slash times to little more than one hour – a massive advantage over the four-hour average by car or five to seven hours by bus – when it opens in 2027.

Mike Reininger, CEO of Brightline Holdings, says: “As the most shovel-ready high-speed rail project in the United States, we are one step closer to leveling the playing field against transit and infrastructure projects around the world, and we are proud to be using America’s most skilled workers to get there.”

Brightline West expects to inject around $10 billion worth of benefits into the region’s economy, creating about 35,000 construction jobs, as well as 1,000 permanent jobs in maintenance, operations and customer service in Southern California and Nevada.

It will also mark the return of passenger trains to Las Vegas after a 30-year hiatus – Amtrak canceled its “Desert Wind” route in 1997.

Brightline hopes to attract around 12 million of the 50 million one-way trips taken annually between Las Vegas and LA, 85% of which are taken by bus or car.

Meanwhile, construction is progressing on another high-speed line through the San Joaquin Valley.

Set to open around 2030, California High Speed Rail (CHSR) will run from Merced to Bakersfield (171 miles) at speeds of up to 220 mph.

Coupled with proposed upgrades to commuter rail lines at either end, this project could eventually allow high-speed trains to run the 350 miles (560 kilometers) between Los Angeles to San Francisco metropolitan areas in just two hours and 40 minutes.

CHSR has been on the table as far back as 1996, but its implementation has been controversial.

Disagreements over the route, management issues, delays in land acquisition and construction, cost over-runs and inadequate funding for completing the entire system have plagued the project – despite the economic benefits it will deliver as well as reducing pollution and congestion. Around 10,000 people are already employed on the project.

Costing $63 billion to $98 billion, depending on the final extent of the scheme, CHSR is to connect six of the 10 largest cities in the state and provide the same capacity as 4,200 miles of new highway lanes, 91 additional airport gates and two new airport runways costing between $122 billion and $199 billion.

With California’s population expected to grow to more than 45 million by 2050, high-speed rail offers the best value solution to keep the state from grinding to a smoggy halt.

Brightline West and CHSR offer templates for the future expansion of high-speed rail in North America.

By focusing on pairs of cities or regions that are too close for air travel and too far apart for car drivers, transportation planners can predict which corridors offer the greatest potential.

“It’s logical that the US hasn’t yet developed a nationwide high-speed network,” says Sherin. “For decades, traveling by car wasn’t a hardship, but as highway congestion gets worse, we’ve reached a stage where we should start looking more seriously at the alternatives.

“The magic numbers are centers of population with around three million people that are 200 to 500 miles apart, giving a trip time of less than three hours – preferably two hours.

“Where those conditions apply in Europe and Asia, high-speed rail reduces air’s share of the market from 100% to near zero. The model would work just as well in the USA as it does globally.”

Sherin points to the success of the original generation of Acela trains as evidence of this.

“When the first generation Acela trains started running between New York City and Washington in 2000, Amtrak attracted so many travelers that the airlines stopped running their frequent ‘shuttles’ between the two cities,” he adds.

However, industry observer Vantuono is more pessimistic.

“A US high-speed rail network is a pipe dream,” he says. “A lack of political support and federal financial support combined with the kind of fierce landowner opposition that CHSR has faced in California means that the challenges for new high-speed projects are enormous.”

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), urban and high-speed rail hold “major promise to unlock substantial benefits” in reducing global transport emissions.

Dr. Fatih Birol, the IEA’s executive director, argues that rail transport is “often neglected” in public debates about future transport systems – and this is especially true in North America.

“Despite the advent of cars and airplanes, rail of all types has continued to evolve and thrive,” adds Birol.

Globally, around three-quarters of rail passenger movements are made on electric-powered vehicles, putting the mode in a unique position to take advantage of the rise in renewable energy over the coming decades.

Here, too, the United States lags far behind the rest of the world, with electrification almost unheard of away from the NEC.

Rail networks in South Korea, Japan, Europe, China and Russia are more than 60% electrified, according to IEA figures, the highest share of track electrification being South Korea at around 85%.

In North America, on the other hand, less than 5% of rail routes are electrified.

The enormous size of the United States and its widely dispersed population mitigates against the creation of a single, unified network of the type being built in China and proposed for Europe.

Air travel is likely to remain the preferred option for transcontinental journeys that can be more than 3,000 miles (around 4,828 kilometers).

But there are many shorter inter-city travel corridors where high-speed rail, or a combination of new infrastructure and upgraded railroad tracks or tilting trains, could eventually provide an unbeatable alternative to air travel and highways.

In the post-pandemic world, while many travelers have been obsessed with airlines, ground stops, cancellations and delays, Amtrak’s ridership is bouncing back — more than doubling in the Northeast corridor, and 88% across the country. At the same time, Amtrak was strengthening its long-haul services, with trains like the Empire Builder, the Zephyr, the Sunset Limited and the Southern Crescent, the Southwest Chief and the Coast Starlight, to name a few.

And while we don’t yet have true high-speed rail yet in this country — and may never have it — there are some improvements in the service. And why don’t we have high-speed rail? Because Amtrak doesn’t own its tracks. The freight lines do, and they have no interest in high-speed rail.

That may also explain why Amtrak doesn’t exactly own a great on-time service record — because their trains often have to pull over to a siding to let a 100-car-long freight train lumber through.

At the same time, Congress has never properly funded Amtrak to allow it to grow and upgrade and to be able to reinvest profits in its product.

In some cases, Amtrak has brought back the dining cars. But even more important, Amtrak has announced a major upgrade to its fleet, with the new “Amtrak Airo” trains — with more spacious interiors and modernized amenities will be rolling out across the U.S. in about three years. The cars will feature more table seating, better legroom and more room for all your electronic devices.

Until then, there’s some good news. Amtrak doesn’t promote it very well, and most passengers don’t know about it, but Amtrak actually sells a USA rail pass. For just $499, you get to travel Amtrak for 30 days and up to 10 rides. It’s a great deal — and children under 12 ride for $250.

And with new high-speed routes launching in several European countries in the past few months — Spain, in particular, has new options for travelers as train operators compete and prices fall — train travel in Europe is an increasingly attractive option.

The Eurail Pass has never been a better deal. It now enables rail travel in 33 European countries, an expansion from the initial 13 countries, with prices starting at $218. One Eurail pass for $473 gives you two months of train travel.

One caveat: you must buy your Eurail pass in conjunction with your roundtrip airline ticket from the U.S. to Europe. You can’t purchase it once you get there. And you can even get a Eurail pass that’s valid for three months.

Press play to listen to this article

LIVERPOOL, England — On the long picket line outside the gates of Liverpool’s Peel Port, rain-soaked dock workers warm themselves with cups of tea as they listen to 1980s pop.

Dozens of buses, cars and trucks honk in solidarity as they pass.

Dockers’ strikes are not new to Liverpool, nor is depravation. But this latest walk-out at Britain’s fourth-largest port is part of something much bigger, a great wave of public and private sector strikes taking place across the U.K. Railways, postal services, law courts and garbage collections are among the many public services grinding to a halt.

The immediate cause of the discontent, as elsewhere, is the rising cost of living. Inflation in the United Kingdom breached the 10 percent mark this year, with wages failing to keep pace.

But the U.K.’s economic woes long predate the current crisis. For more than a decade, Britain has been beset by weak economic growth, anaemic productivity, and stagnant private and public sector investment. Since 2016, its political leadership has been in a state of Brexit-induced flux.

Half a century after U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger looked at the U.K.’s 1970s economic malaise and declared that “Britain is a tragedy,” the United Kingdom is heading to be the sick man of Europe once again.

Here in Liverpool, the “scars run very deep,” said Paul Turking, a dock worker in his late 30s. British voters, he added, have “been misled” by politicians’ promises to “level up” the country by investing heavily in regional economies. Conservatives “will promise you the world and then pull the carpet out from under your feet,” he complained.

“There’s no middle class no more,” said John Delij, a Peel Port veteran of 15 years. He sees the cost-of-living crisis and economic stagnation whittling away the middle rung of the economic ladder.

“How many billionaires do we have?” Delij asked, wondering how Britain could be the sixth-largest economy in the world with a record number of billionaires when food bank use is 35 percent above its pre-pandemic level. “The workers put money back into the economy,” he said.

What would they do if they were in charge? “Invest in affordable housing,” said Turking. “Housing and jobs.”

The British economy has been struck by particular turbulence over recent weeks. The cost of government borrowing soared in the wake of former PM Liz Truss’ disastrous mini-budget on September 23, with the U.K.’s central bank forced to step in and steady the bond markets.

But while the swift installation of Rishi Sunak, the former chancellor, as prime minister seems to have restored a modicum of calm, the economic backdrop remains bleak. Spending and welfare cuts are coming. Taxes are certain to rise. And the underlying problems cut deep.

U.K. productivity growth since the financial crisis has trailed that of comparator nations such as the U.S., France and Germany. As such, people’s median incomes also lag behind neighboring countries over the same period. Only Russia is forecast to have worse economic growth among the G20 nations in 2023.

In 1976, the U.K. — facing stagflation, a global energy crisis, a current account deficit and labor unrest — had to be bailed out by the International Monetary Fund. It feels far-fetched, but today some are warning it could happen again.

The U.K. is spluttering its way through an illness brought about in part through a series of self-inflicted wounds that have undermined the basic pillars of any economy: confidence and stability.

The political and economic malaise is such that it has prompted unwanted comparisons with countries whose misfortunes Britain once watched amusedly from afar.

“The existential risk to the U.K. … is not that we’re suddenly going to go off an economic cliff, or that the country’s going to descend into civil war or whatever,” said Jonathan Portes, professor of economics at King’s College London. “It’s that we will become like Italy.”

Portes, of course, does not mean a country blessed with good weather and fine food — but an economy hobbled by persistently low growth, caught in a dysfunctional political loop that lurches between “corrupt and incompetent right-wing populists” and “well-intentioned technocrats who can’t actually seem to turn the ship around.”

“That’s not the future that we want in the U.K,” he said.

Reviving the U.K.’s flatlining economy will not happen overnight. As Italy’s experience demonstrates, it’s one thing to diagnose an illness — another to cure it.

Experts speak of an unbalanced model heavily reliant upon Britain’s services sector and beset with low productivity, a result of years of underinvestment and a flexible labor market which delivers low unemployment but often insecure and low-paid work.

“We’re not investing in skills; businesses aren’t investing,” said Xiaowei Xu, senior research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies. “It’s not that surprising that we’re not getting productivity growth.”

But any attempt to address the country’s ailments will require its economic stewards to understand their underlying causes — and those stretch back at least to the first truly global crisis of the 21st century.

The 2008 financial crisis hammered economies around the world, and the U.K. was no exception. Its economy shrunk by more than 6 percent between the first quarter of 2008 and the second quarter of 2009. Five years passed before it returned to its pre-recession size.

For Britain, the crisis in fact began in September 2007, a year before the collapse of Lehman Brothers, when wobbles in the U.S. subprime mortgage market sparked a run on the British bank Northern Rock.

The U.K. discovered it was particularly vulnerable to such a shock. Over the second half of the 20th century, its manufacturing base had largely eroded as its services sector expanded, with financial and professional services and real estate among the key drivers. As the Bank of England put it: “The interconnectedness of global finance meant that the U.K. financial system had become dangerously exposed to the fall-out from the U.S. sub-prime mortgage market.”

The crisis was a “big shock to the U.K.’s broad economic model,” said John Springford, from the Centre for European Reform. Productivity took an immediate hit as exports of financial services plunged. It never fully recovered.

“Productivity before the crash was basically, ‘Can we create lots and lots of debt and generate lots and lots of income on the back of this? Can we invent collateralized debt obligations and trade them in vast volumes?’” said James Meadway, director of the Progressive Economy Forum and a former adviser to Labour’s left-wing former shadow chancellor, John McDonnell.

A post-crash clampdown on City practises had an obvious impact.

“This is a major part of the British economy, so if it’s suddenly not performing the way it used to — for good reasons — things overall are going to look a bit shaky,” Meadway added.

The shock did not contain itself to the economy. In a pattern that would be repeated, and accentuated, in the coming years, it sent shuddering waves through the country’s political system, too.

The 2010 election was fought on how to best repair Britain’s broken economy. In 2009, the U.K. had the second-highest budget deficit in the G7, trailing only the U.S., according to the U.K. government’s own fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

The Conservative manifesto declared “our economy is overwhelmed by debt,” and promised to close the U.K.’s mounting budget deficit in five years with sharp public sector cuts. The incumbent Labour government responded by pledging to halve the deficit by 2014 with “deeper and tougher” cuts in public spending than the significant reductions overseen by former Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s.

The election returned a hung parliament, with the Conservatives entering into a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. The age of austerity was ushered in.

Defenders of then-Chancellor George Osborne’s austerity program insist it saved Britain from the sort of market-led calamity witnessed this fall, and put the U.K. economy in a condition to weather subsequent global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the fallout from the war in Ukraine.

“That hard work made policies like furlough and the energy price cap possible,” said Rupert Harrison, one of Osborne’s closest Treasury advisers.

Pointing to the brutal market response to Truss’ freewheeling economic plans, Harrison praised the “wisdom” of the coalition in prioritizing tackling the U.K.’s debt-GDP ratio. “You never know when you will be vulnerable to a loss of credibility,” he noted.

But Osborne’s detractors argue austerity — which saw deep cuts to community services such as libraries and adult social care; courts and prisons services; road maintenance; the police and so much more — also stripped away much of the U.K.’s social fabric, causing lasting and profound economic damage. A recent study claimed austerity was responsible for hundreds of thousands of excess deaths.

Under Osborne’s plan, three-quarters of the fiscal consolidation was to be delivered by spending cuts. With the exception of the National Health Service, schools and aid spending, all government budgets were slashed; public sector pay was frozen; taxes (mainly VAT) rose.

But while the government came close to delivering its fiscal tightening target for 2014-15, “the persistent underperformance of productivity and real GDP over that period meant the deficit remained higher than initially expected,” the OBR said. By his own measure, Osborne had failed, and was forced to push back his deficit-elimination target further. Austerity would have to continue into the second half of the 2010s.

Many economists contend that the fiscal belt-tightening sucked demand out of the economy and worsened Britain’s productivity crisis by stifling investment. “That certainly did hit U.K. growth and did some permanent damage,” said King’s College London’s Portes.

“If that investment isn’t there, other people start to find it less attractive to open businesses,” former Labour aide Meadway added. “If your railways aren’t actually very good … it does add up to a problem for businesses.”

A 2015 study found U.K. productivity, as measured by GDP per hour worked, was now lower than in the rest of the G7 by a whopping 18 percentage points.

“Frankly, nobody knows the whole answer,” Osborne said of Britain’s productivity conundrum in May 2015. “But what I do know is that I’d much rather have the productivity challenge than the challenge of mass unemployment.”

Rising employment was indeed a signature achievement of the coalition years. Unemployment dropped below 6 percent across the U.K. by the end of the parliament in 2015, with just Germany and Austria achieving a lower rate of joblessness among the then-28 EU states. Real-term wages, however, took nearly a decade to recover to pre-crisis levels.

Economists like Meadway contend that the rise in employment came with a price, courtesy of Britain’s famously flexible labor market. He points to a Sports Direct warehouse in the East Midlands, where a 2015 Guardian investigation revealed the predominantly immigrant workforce was paid illegally low wages, while the working conditions were such that the facility was nicknamed “the gulag.”

The warehouse, it emerged, was built on a former coal mine, and for Meadway the symbolism neatly charts the U.K.’s move away from traditional heavy industry toward more precarious service sector employment. “It’s not a secure job anymore,” he said. “Once you have a very flexible labor market, the pressure on employers to pay more and the capacity for workers to bargain for more is very much reduced.”

Throughout the period, the Bank of England — the U.K.’s central bank — kept interest rates low and pursued a policy of quantitative easing. “That tends to distort what happens in the economy,” argued Meadway. QE, he said, is a “good [way of] getting money into the hands of people who already have quite a lot” and “doesn’t do much for people who depend on wage income.”

Meanwhile — whether necessary or not — the U.K.’s austerity policies undoubtedly worsened a decades-long trend of underinvestment in skills and research and development (Britain lags only Italy in the G7 on R&D spending). At British schools, there was a 9 percent real terms fall in per-pupil spending between 2009 and 2019, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies’ Xu. “As countries get richer, usually you start spending more on education,” Xu noted.

Two senior ministers in the coalition government — David Gauke, who served in the Treasury throughout Osborne’s tenure, and ex-Lib Dem Business Secretary Vince Cable — have both accepted that the government might have focused more on higher taxation and less on cuts to public spending. But both also insisted the U.K had ultimately been correct to prioritize putting its public finances on a sounder footing.

It was February 2018 before Britain finally achieved Osborne’s goal of eliminating the deficit on its day-to-day budget.

Austerity was coming to an end, at last. But Osborne had already left the Treasury, 18 months earlier — swept away along with Cameron in the wake of a seismic national uprising.

***

David Cameron had won the 2015 election outright, despite — or perhaps because of — the stringent spending cuts his coalition government had overseen, more of which had been pledged in his 2015 manifesto. Also promised, of course, was a public vote on Britain’s EU membership.

The reasons for the leave vote that followed were many and complex — but few doubt that years of underinvestment in poorer parts of the U.K. were among them.

Regardless, the 2016 EU referendum triggered a period of political acrimony and turbulence not seen in Westminster for generations. With no pre-agreed model of what Brexit should actually entail, the U.K.’s future relationship with the EU became the subject of heated and protracted debate. After years of wrangling, Britain finally left the bloc at the end of January 2020, severing ties in a more profound way than many had envisaged.

While the twin crises of COVID and Ukraine have muddled the picture, most economists agree Brexit has already had a significant impact on the U.K. economy. The size of Britain’s trade flows relative to GDP has fallen further than other G7 countries, business investment growth trails the likes of Japan, South Korea and Italy, and the OBR has stuck by its March 2020 prediction that Brexit would reduce productivity and U.K. GDP by 4 percent.

Perhaps more significantly, Brexit has ushered in a period of political instability. As prime ministers come and go (the U.K. is now on its fifth since 2016), economic programs get neglected, or overturned. Overseas investors look on with trepidation.

“The evidence that the referendum outcome, and the kind of uncertainty and change in policy that it created, have led to low investment and low growth in the U.K. is fairly compelling,” said professor Stephen Millard, deputy director at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

Beyond the instability, the broader impact of the vote to leave remains contentious.

Portes argued — as many Remain supporters also do — that much harm was done by the decision to leave the EU’s single market. “It’s the facts, not the uncertainty that in my view is responsible for most of the damage,” he said.

Brexit supporters dismiss such claims.

“It’s difficult statistically to find much significant effect of Brexit on anything,” said professor Patrick Minford, founder member of Economists for Brexit. “There’s so much else going on, so much volatility.”

Minford, an economist favored by ex-PM Truss, acknowledged that “Brexit is disruptive in the short run, so it’s perfectly possible that you would get some short-run disruption.” But he added: “It was a long-term policy decision.”

Plenty of economists can rattle off possible solutions, although actually delivering them has thus far evaded Britain’s political class. “It’s increasing investment, having more of a focus on the long-term, it’s having economic strategies that you set out and actually commit to over time,” says the IFS’ Xu. “As far as possible, it’s creating more certainty over economic policy.”

But in seeking to bring stability after the brief but chaotic Truss era, new U.K. Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has signaled a fresh period of austerity is on the way to plug the latest hole in the nation’s finances. Leveling Up Secretary Michael Gove told Times Radio that while, ideally, you wouldn’t want to reduce long-term capital investments, he was sure some spending on big projects “will be cut.”

This could be bad news for many of the U.K.’s long-awaited infrastructure schemes such as the HS2 high-speed rail line, which has been in the works for almost 15 years and already faces a familiar mix of local resistance, vested interests, and a sclerotic planning system.

“We have a real problem in the sense that the only way to really durably raise productivity growth for this country is for investments to pick up,” said Springford, from the Centre for European Reform. “And the headwinds to that are quite significant.”

For dock workers at Liverpool’s Peel Port, the prospect of a fresh round of austerity amid a cost-of-living crisis is too much to bear. “Workers all over this country need to stand up for themselves and join a union,” insisted Delij.

For him, it’s all about priorities — and the arguments still echo back to the great crash of 15 years ago. “They bailed the bankers out in 2007,” he said, “and can’t bail hungry people out now.”

Sebastian Whale and Graham Lanktree

Source link