Those on a healthy plant-based diet who have elevated homocysteine levels despite taking sufficient vitamin B12 may want to consider taking a gram a day of contaminant-free creatine.

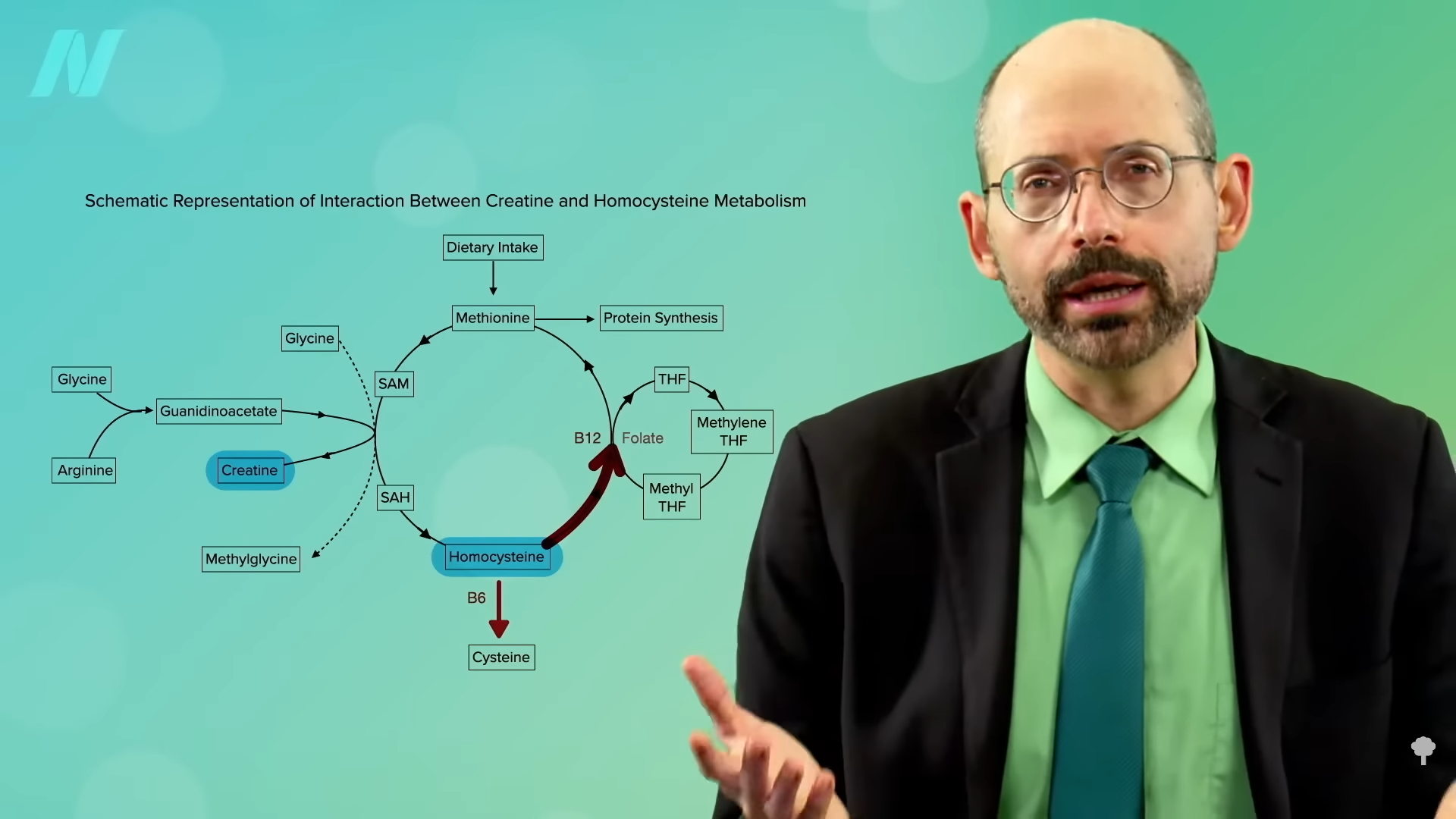

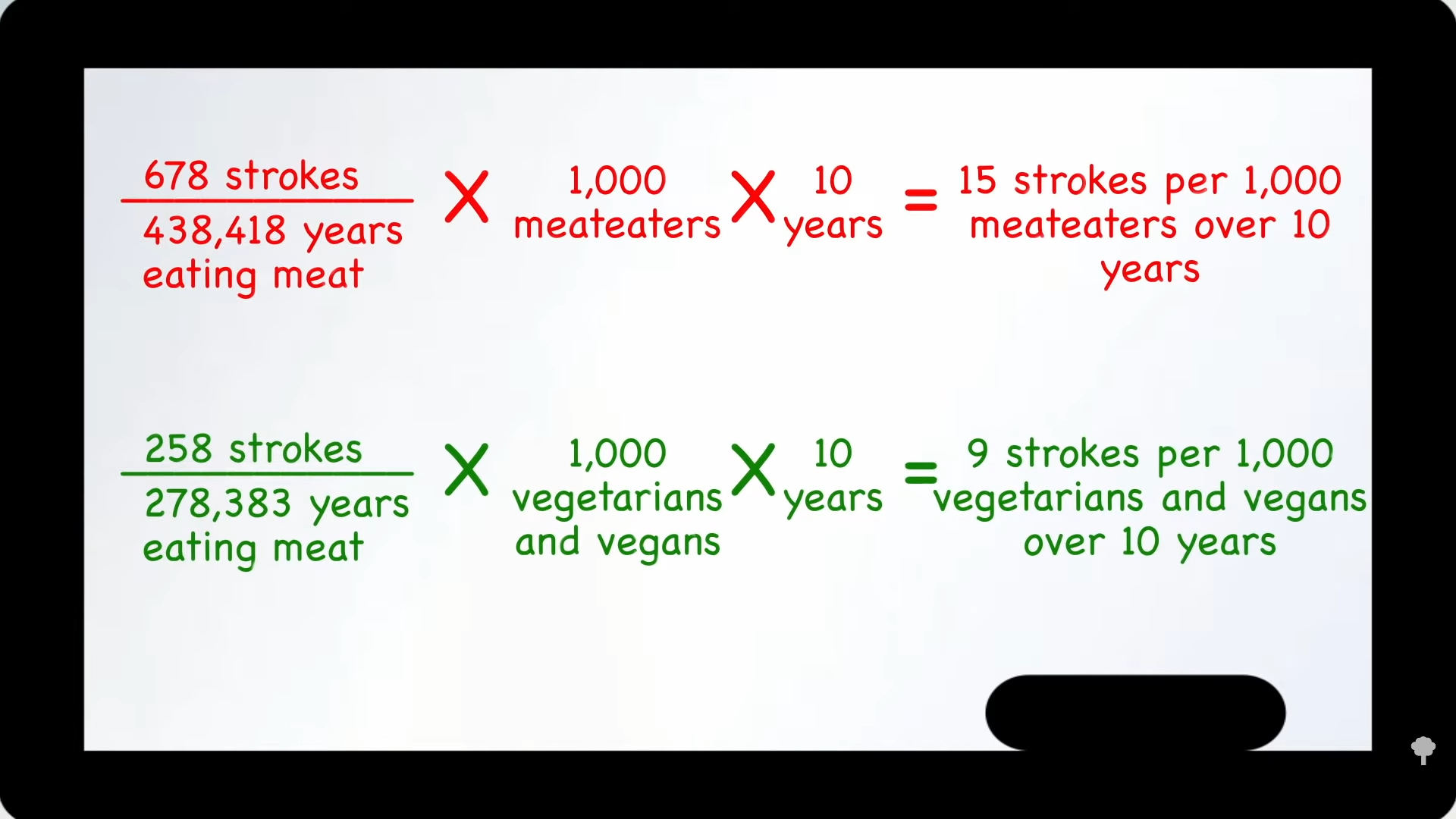

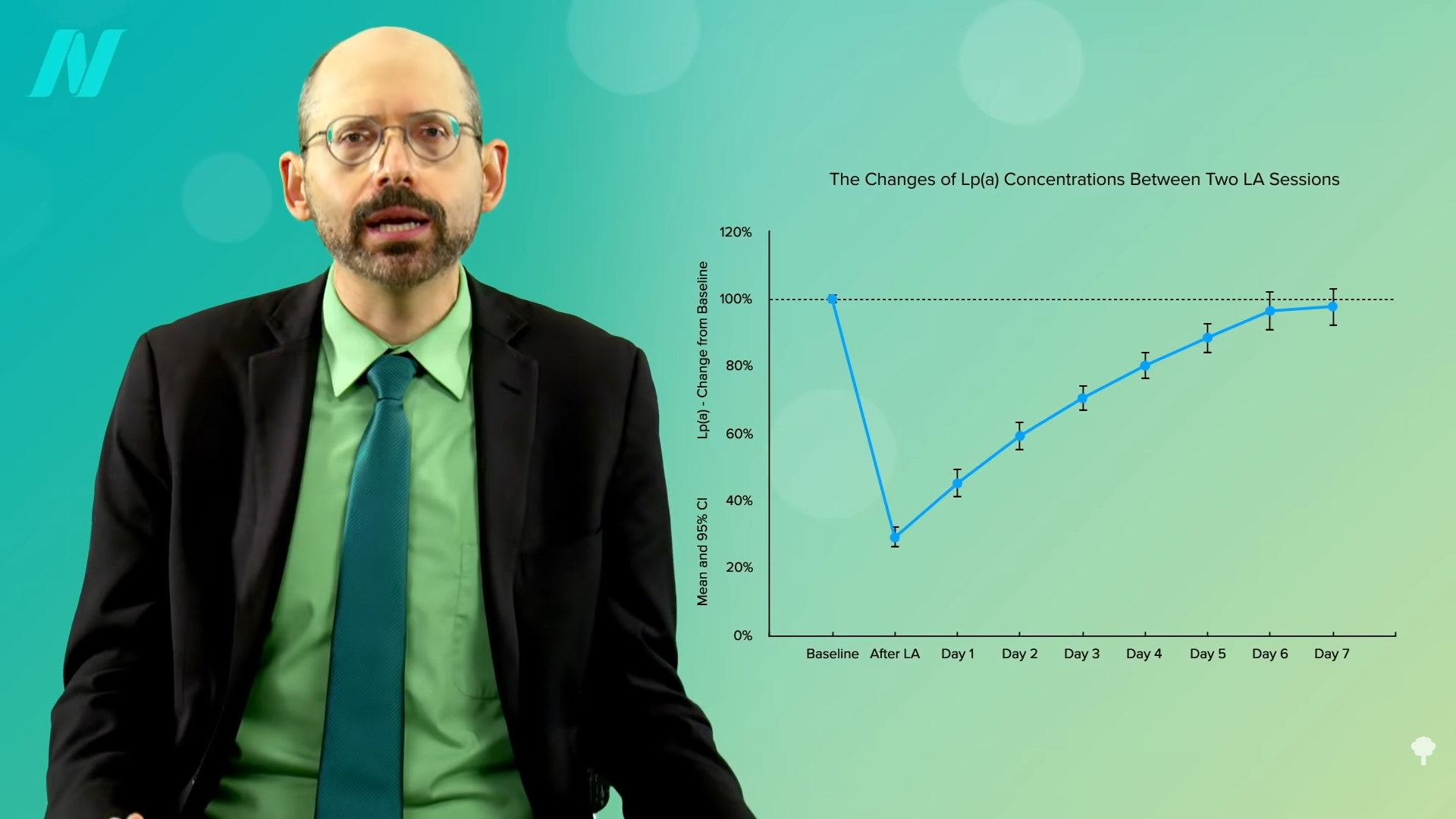

The average blood levels of homocysteine in men are about 1.5 points higher than in women, which may be one of the reasons men tend to be at higher risk for cardiovascular disease. Women don’t need to make as much creatine as men since they tend to have less muscle mass. That may help explain “the ‘gender gap’ in homocysteine levels.” If you remember from my previous video and as seen below and at 0:36 in The Efficacy and Safety of Creatine for High Homocysteine, in the process of making creatine, our body produces homocysteine as a by-product. So, for people with stubbornly high homocysteine levels that don’t respond sufficiently to B vitamins, “creatine supplementation may represent a practical strategy for decreasing plasma homocysteine levels”—that is, lowering the level of homocysteine into the normal range.

It seemed to work in rats. What about humans? Well, it worked in one study, but it didn’t seem to work in another. It didn’t work in yet another either. And, in another study, homocysteine levels were even driven up. So, this suggestion that taking creatine supplements would lower homocysteine was called into question.

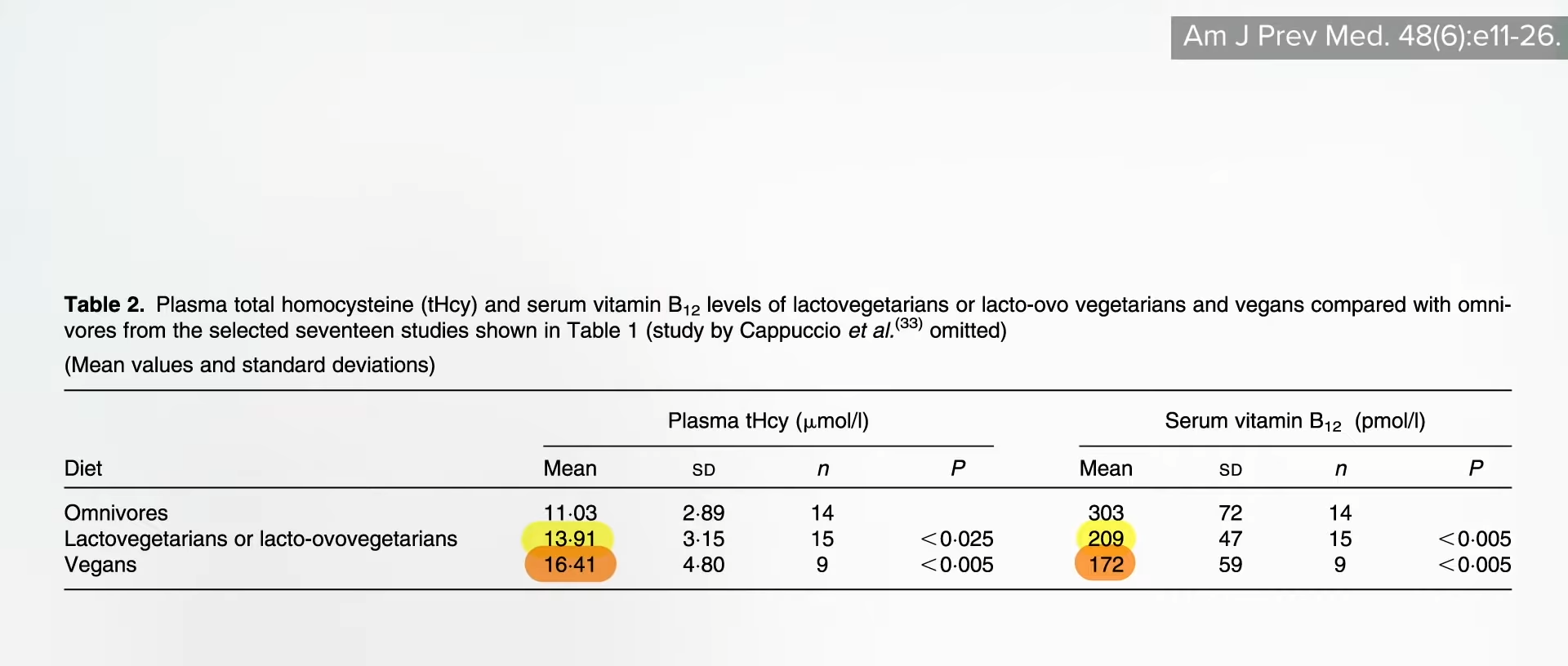

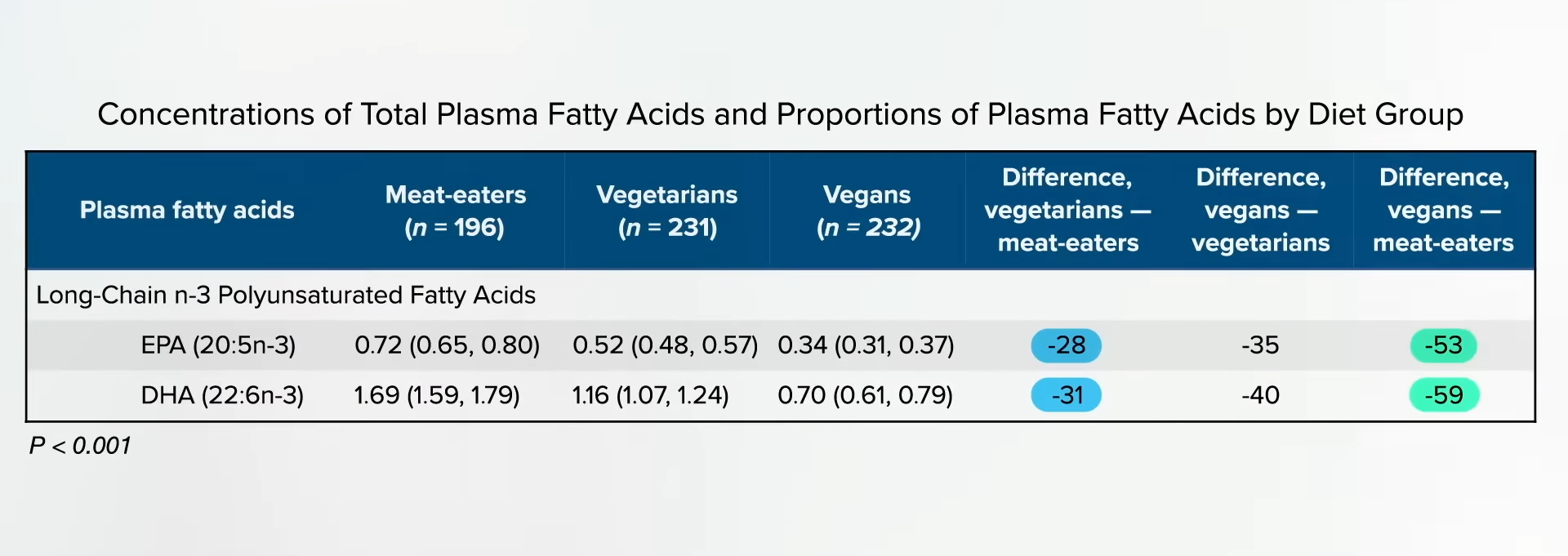

However, all those studies were done with non-vegetarians, so they were already effectively supplementing with creatine every day in the form of muscle meat. In that way, researchers were testing higher versus lower supplementation. Those eating strictly plant-based make all their creatine from scratch, so they may be more sensitive to an added creatine source. There weren’t any studies on creatine supplementation in vegans to lower homocysteine until now.

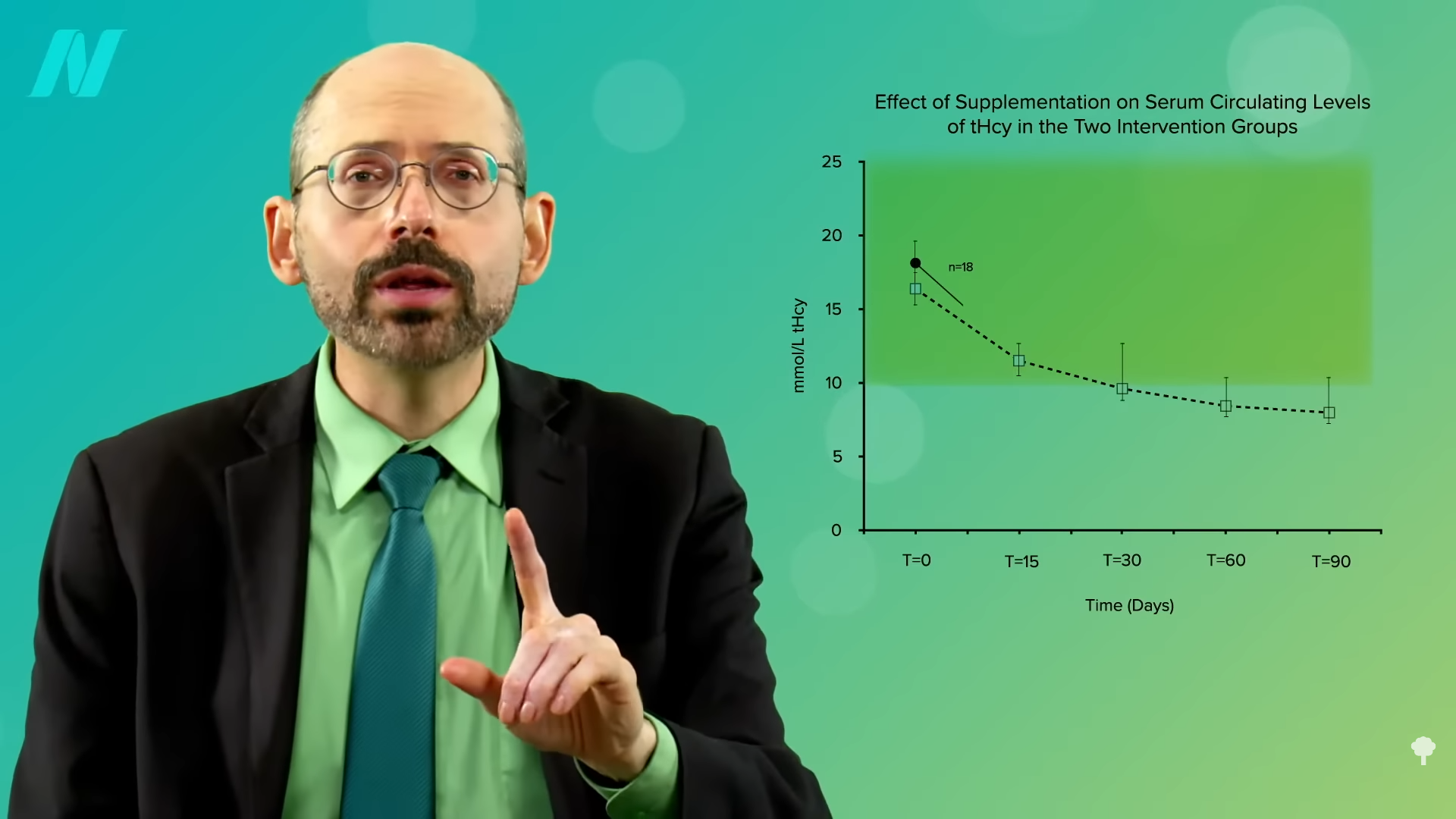

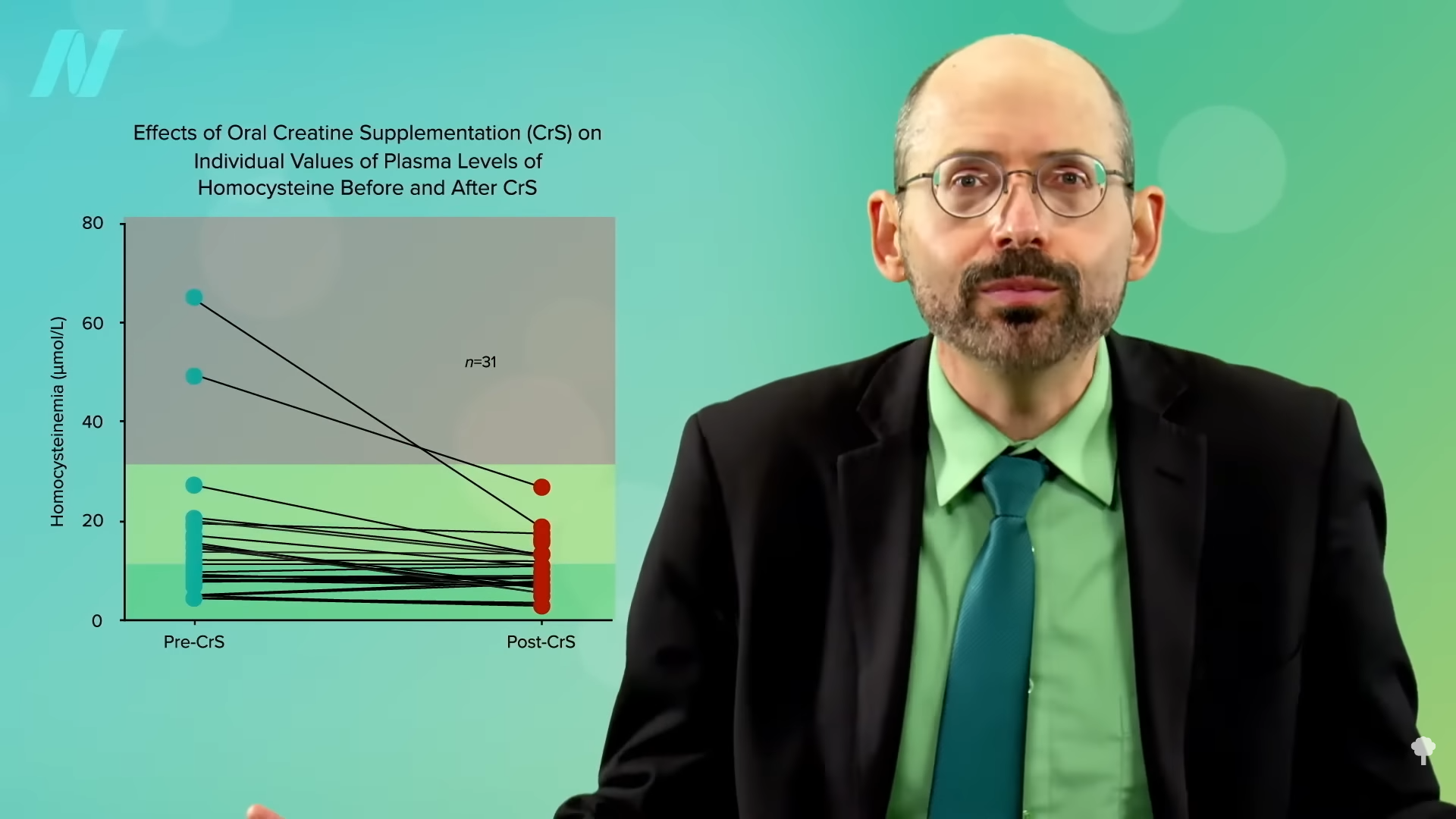

Researchers took vegans who were not supplementing their diets with vitamin B12, so some of their homocysteine levels were through the roof. A few were as high as 50 when the ideal is more like under 10, for example. After taking some creatine for a few weeks, all of their homocysteine levels normalized. You can see the before and after in the graph below and at 2:04 in my video.

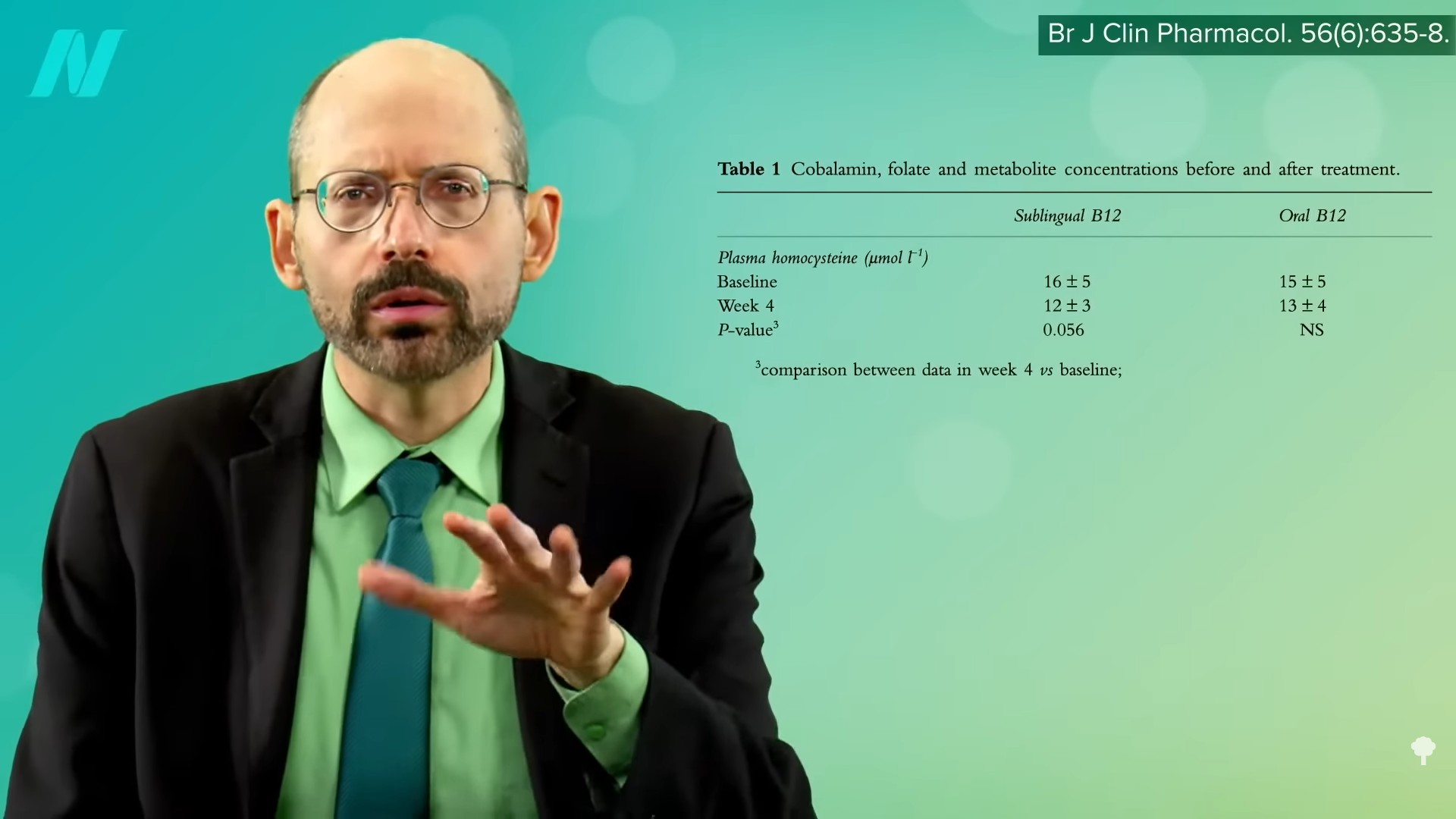

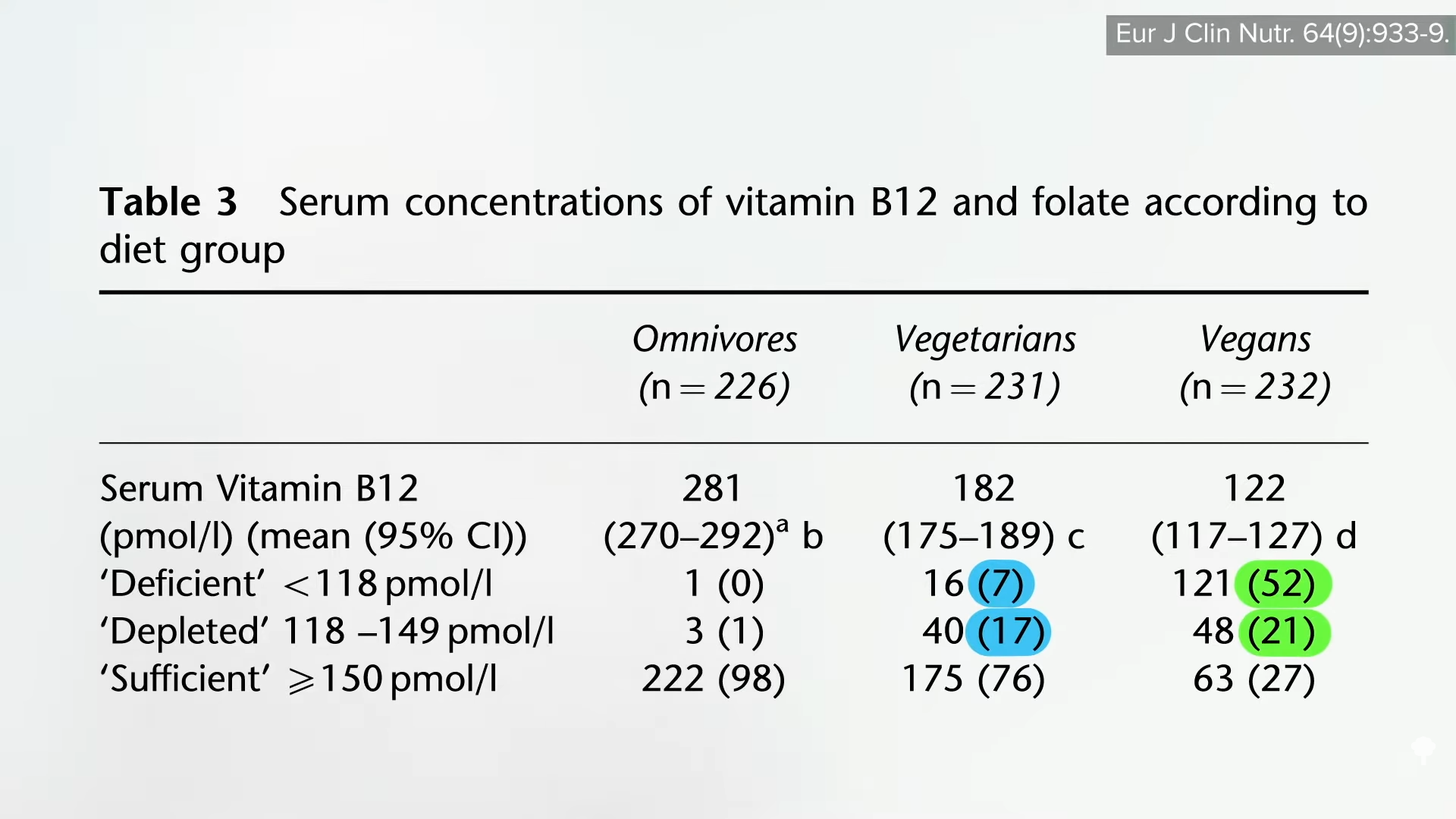

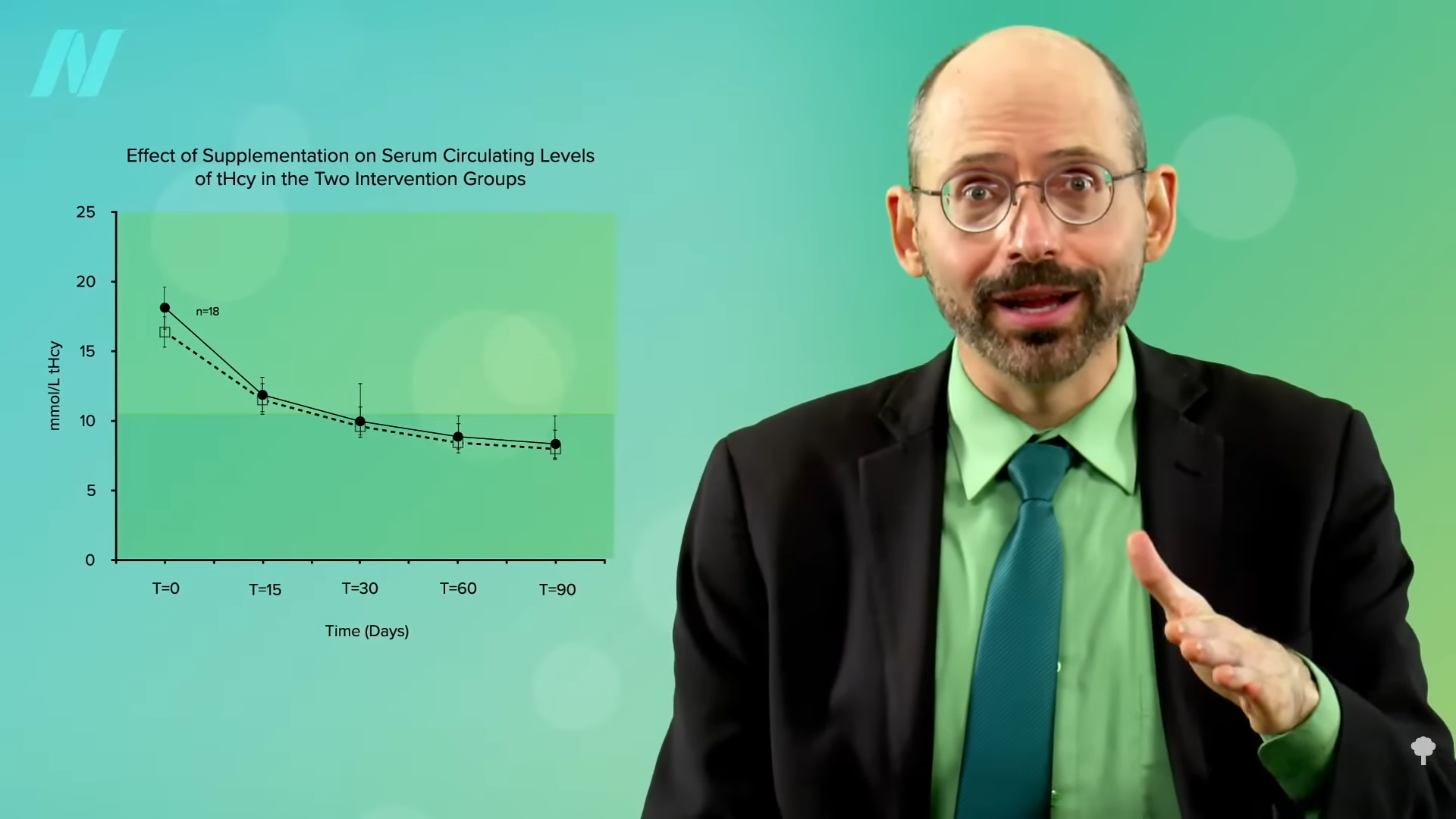

Now, they didn’t normalize, as that would have been a level under 10, but that’s presumably because they weren’t taking any B12. Give vegetarians and vegans vitamin B12 supplements, either dosing daily or once a week, and their levels normalize in a matter of months, as you can see below and at 2:20 in my video. However, the fact that you could bring down homocysteine levels with creatine alone, even without any B12, suggests—to me at least—that if your homocysteine is elevated (above 10) on a plant-based diet despite taking B12 supplements and eating greens and beans to get enough folate, it might be worth experimenting with supplementing with a gram of creatine a day for a few weeks to see if your homocysteine comes down.

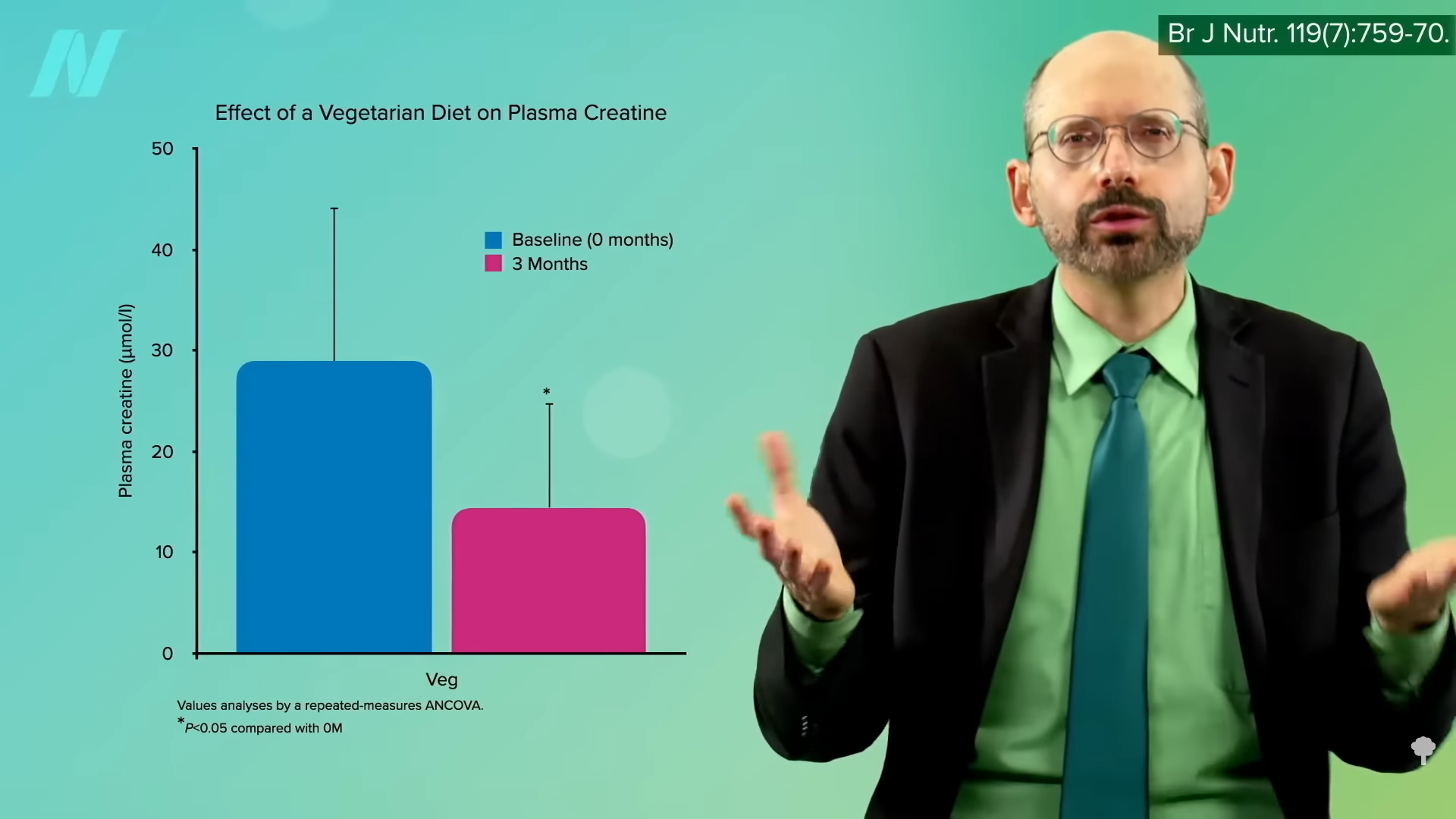

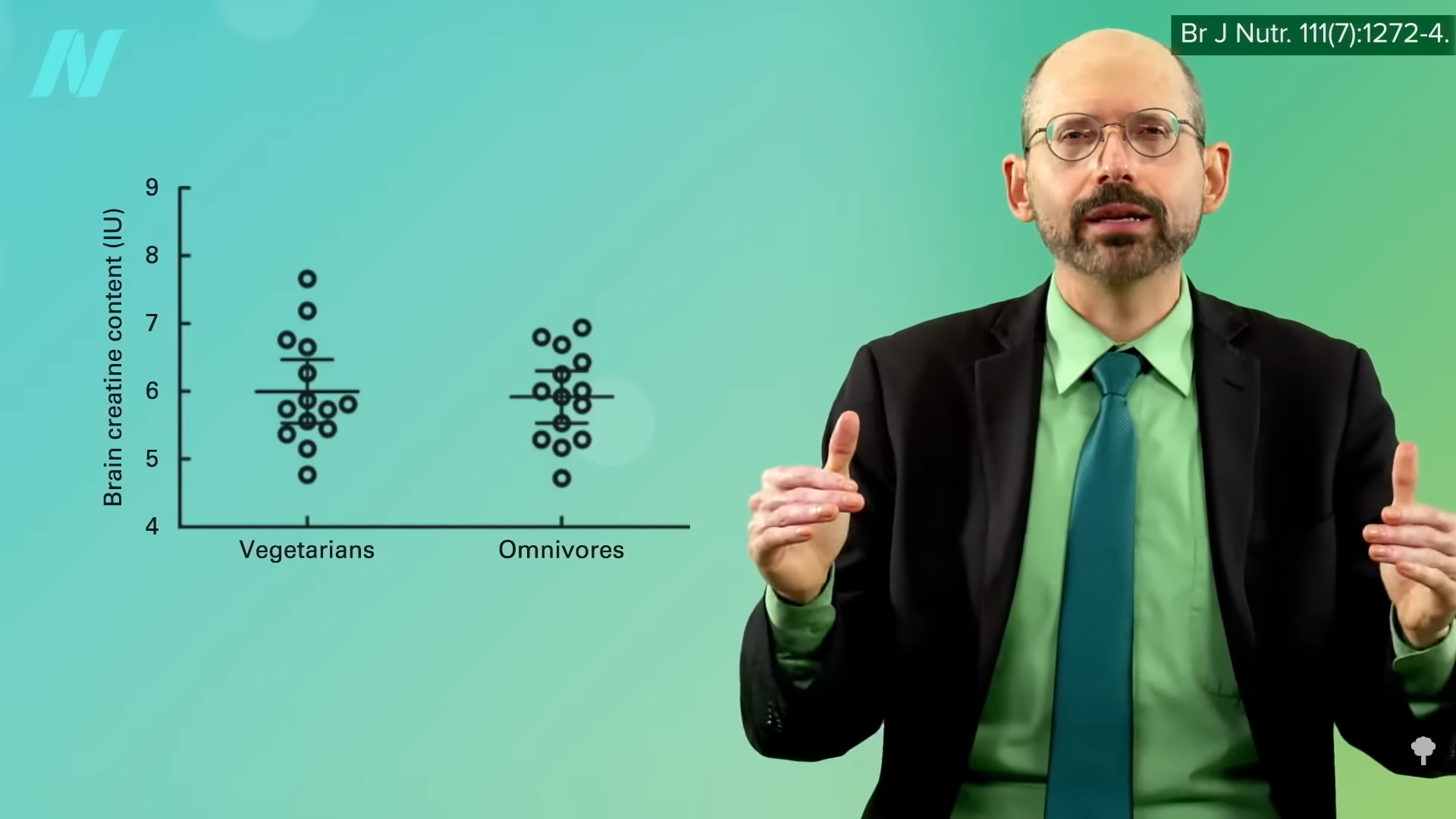

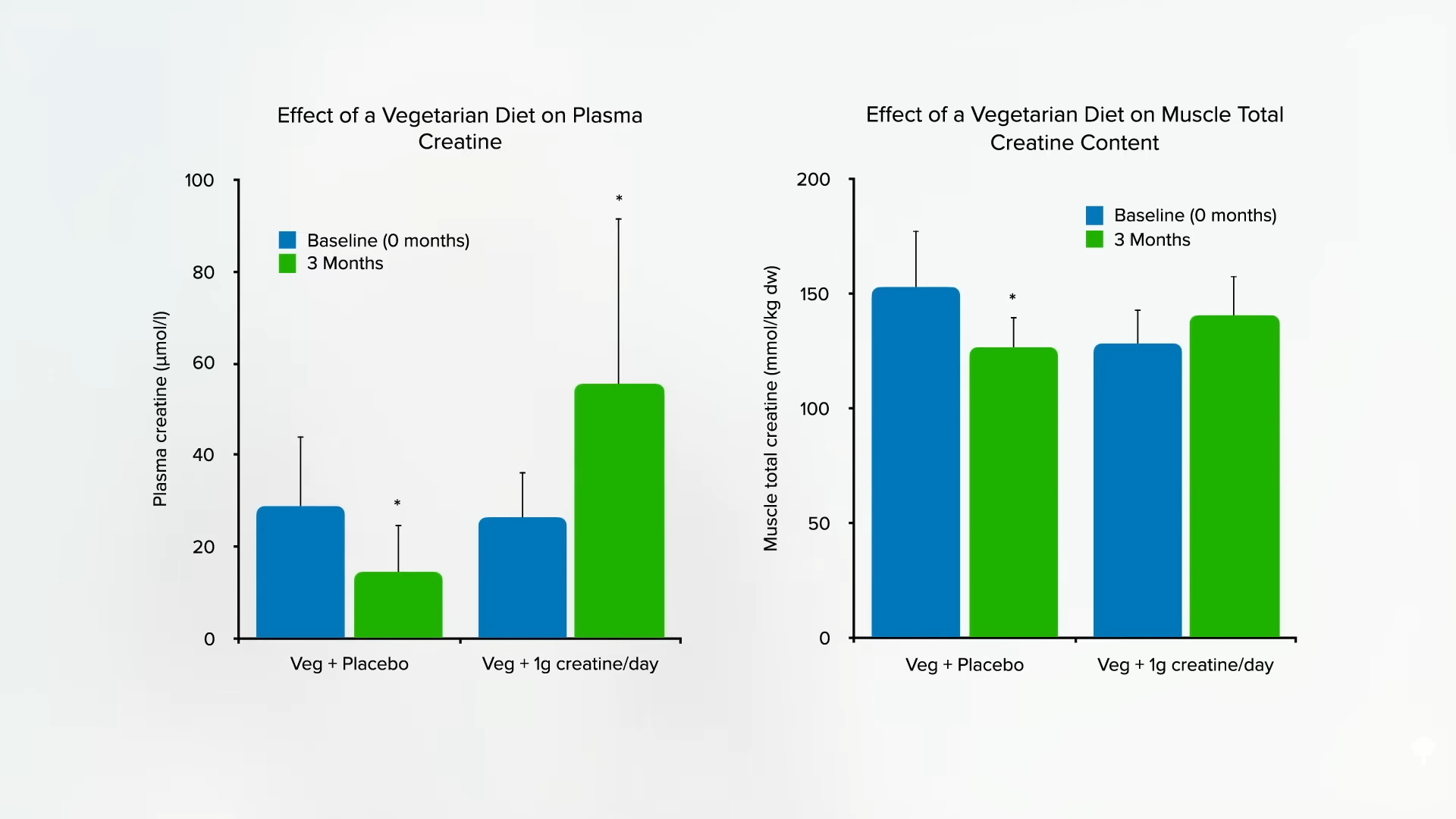

Why just a single gram? That’s approximately how much non-vegetarians do not have to make themselves; it’s the amount that erased vegetarian discrepancies in blood and muscle, as you can see in the graph below and at 3:01 in my video, and how much has been shown to be safe in the longer term.

How safe is it? We can take a bit of comfort in the fact that it’s “one of the world’s best-selling dietary supplements,” with literally billions of servings taken, and the only consistently reported side effect has been weight gain, presumed to be from water retention. The only serious side effects appear to be among those with pre-existing kidney diseases taking whopping doses closer to 20 grams a day. A concern was raised that creatine could potentially form a carcinogen known as N-nitrososarcosine when it hit the acid bath of the stomach, but, when it actually put to the test, researchers found this does not appear to be a problem.

Bottom line: Doses of supplemental creatine up to 3 grams a day are “unlikely to pose any risk,” provided “high purity creatine” is used. However, as we all know, dietary supplements in the United States “are not regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration and may contain contaminants or variable quantities of the desired supplement” and may not even contain what’s on the label. We’re talking about “contaminants…that may be generated during the industrial production.” When researchers looked at 33 samples of creatine supplements made in the United States and Europe, they found that they all actually contained creatine, which is nice, but about half exceeded the maximum level recommended by food safety authorities for at least one contaminant. The researchers recommend that “consumers give their preference to products obtained by producers that ensure the highest quality control and certify the maximum amount of contaminants present in their products.” Easier said than done.

Because of the potential risks, I don’t think people should take creatine supplements willy-nilly, but the potential benefits may exceed the potential risks if, again, you’re on a healthy plant-based diet and taking B12, and your homocysteine levels are still not under 10. In that case, I would suggest giving a gram a day of creatine a trying to see if it brings it down.

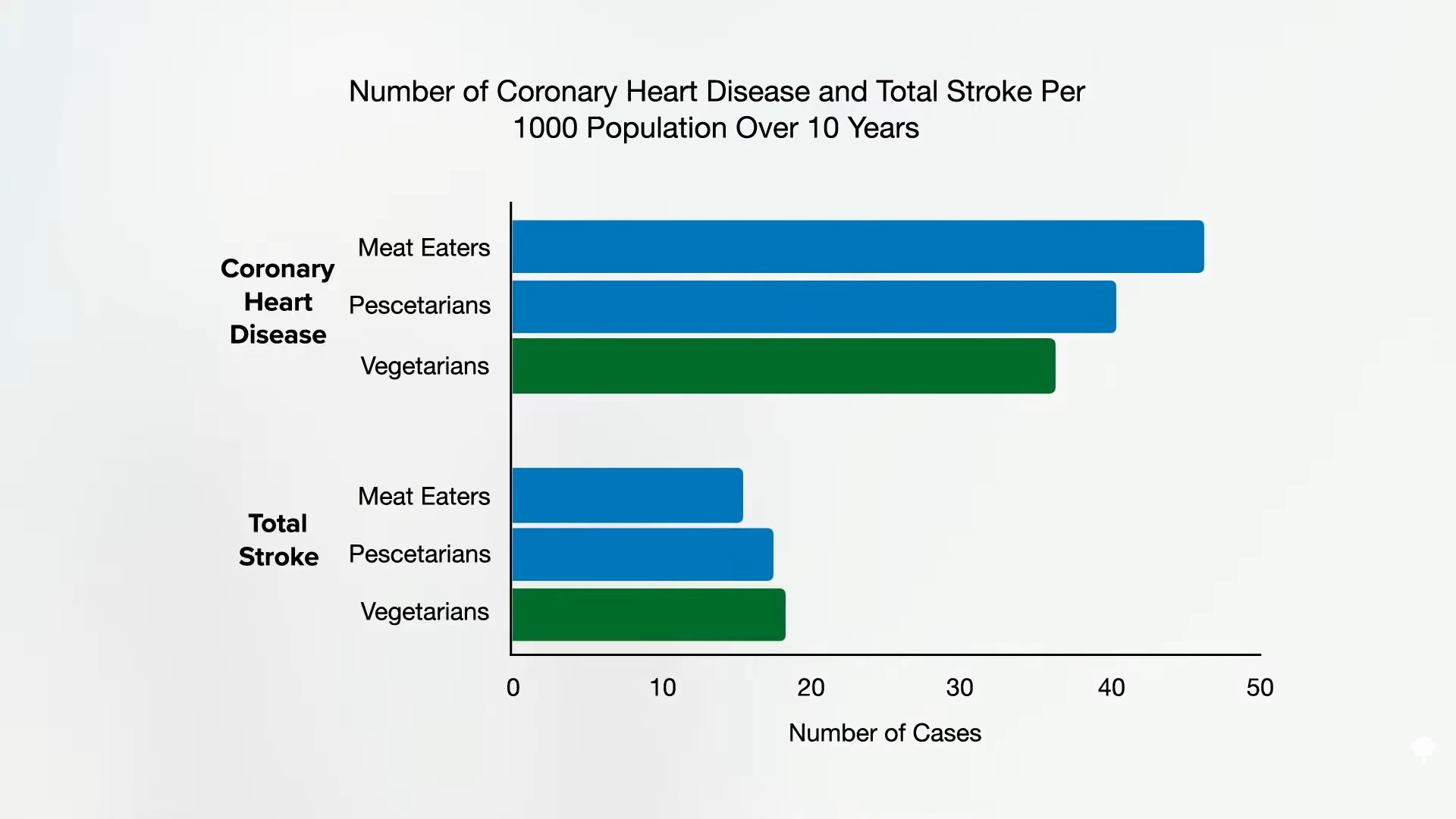

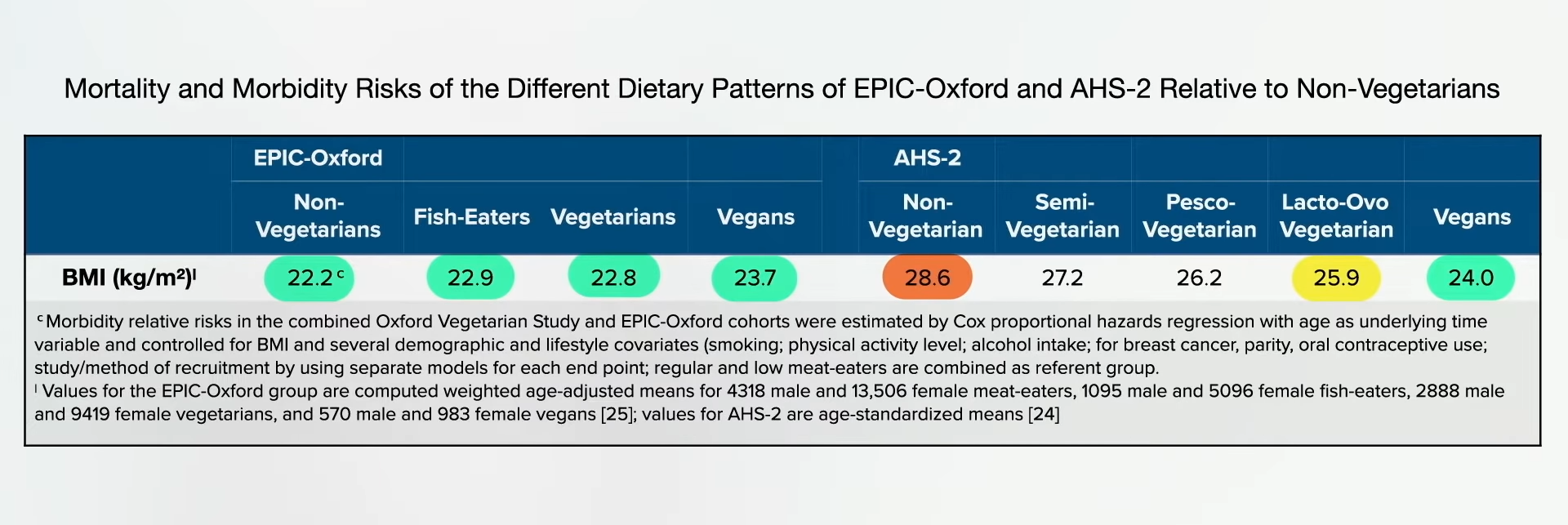

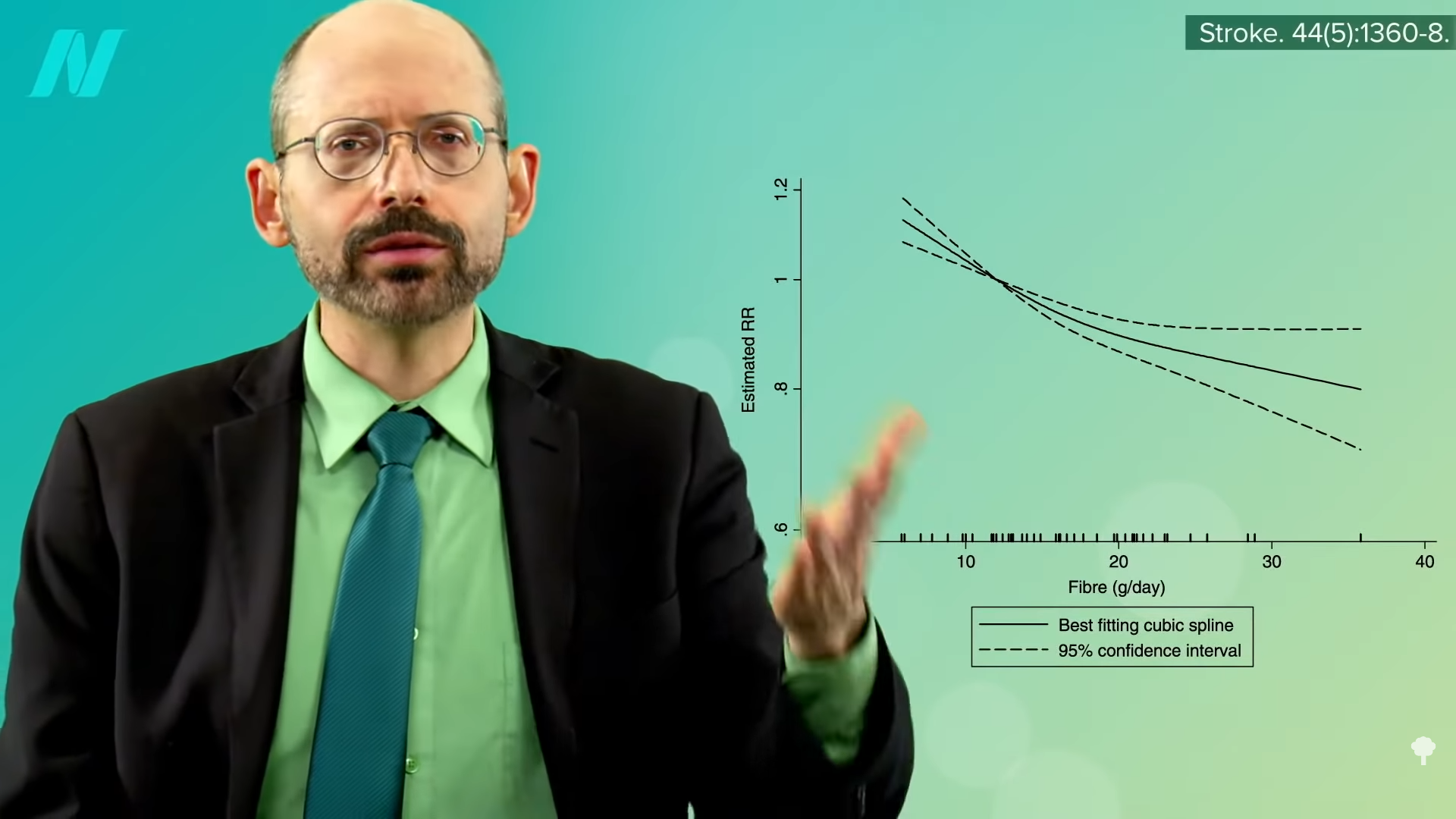

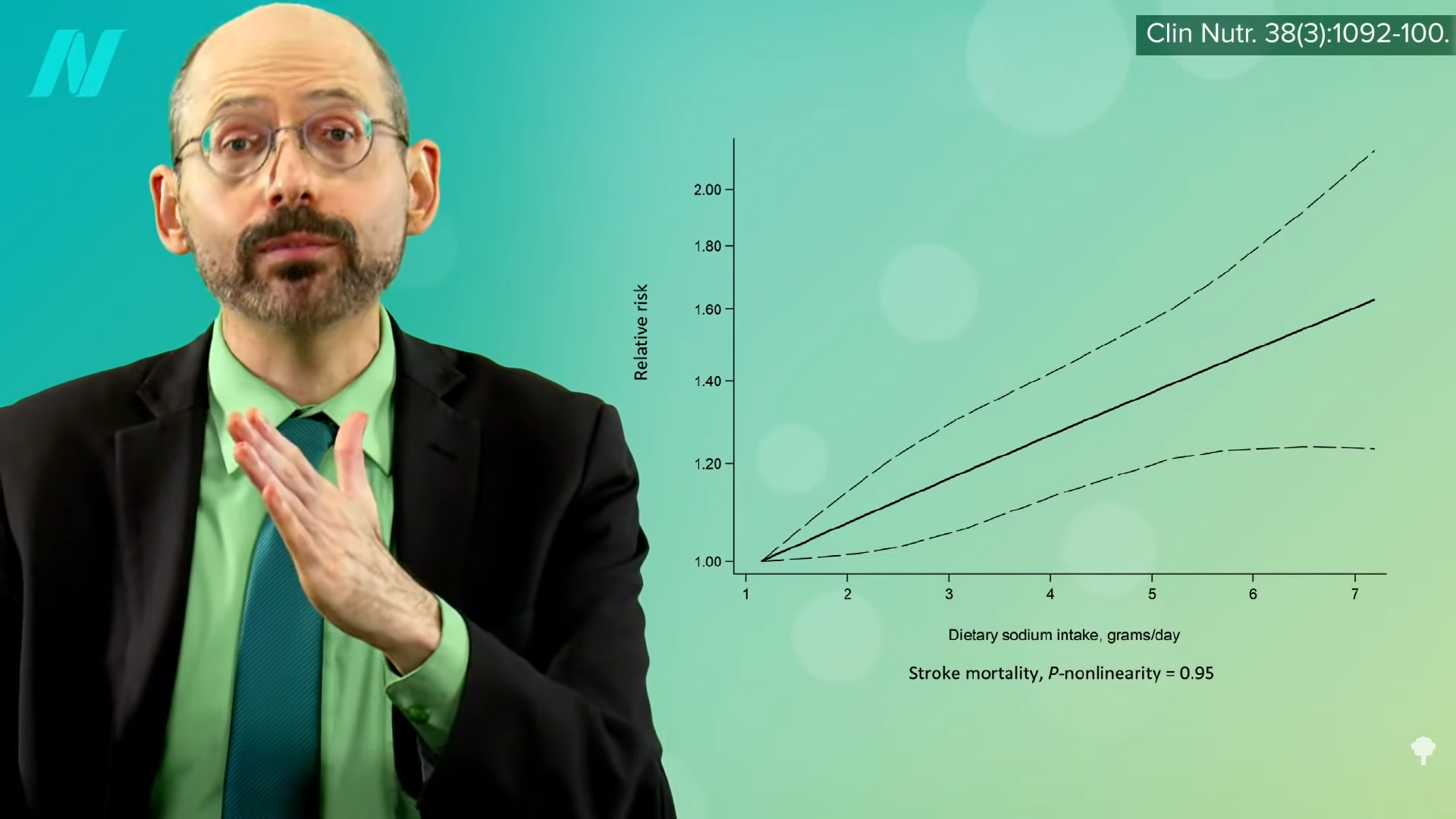

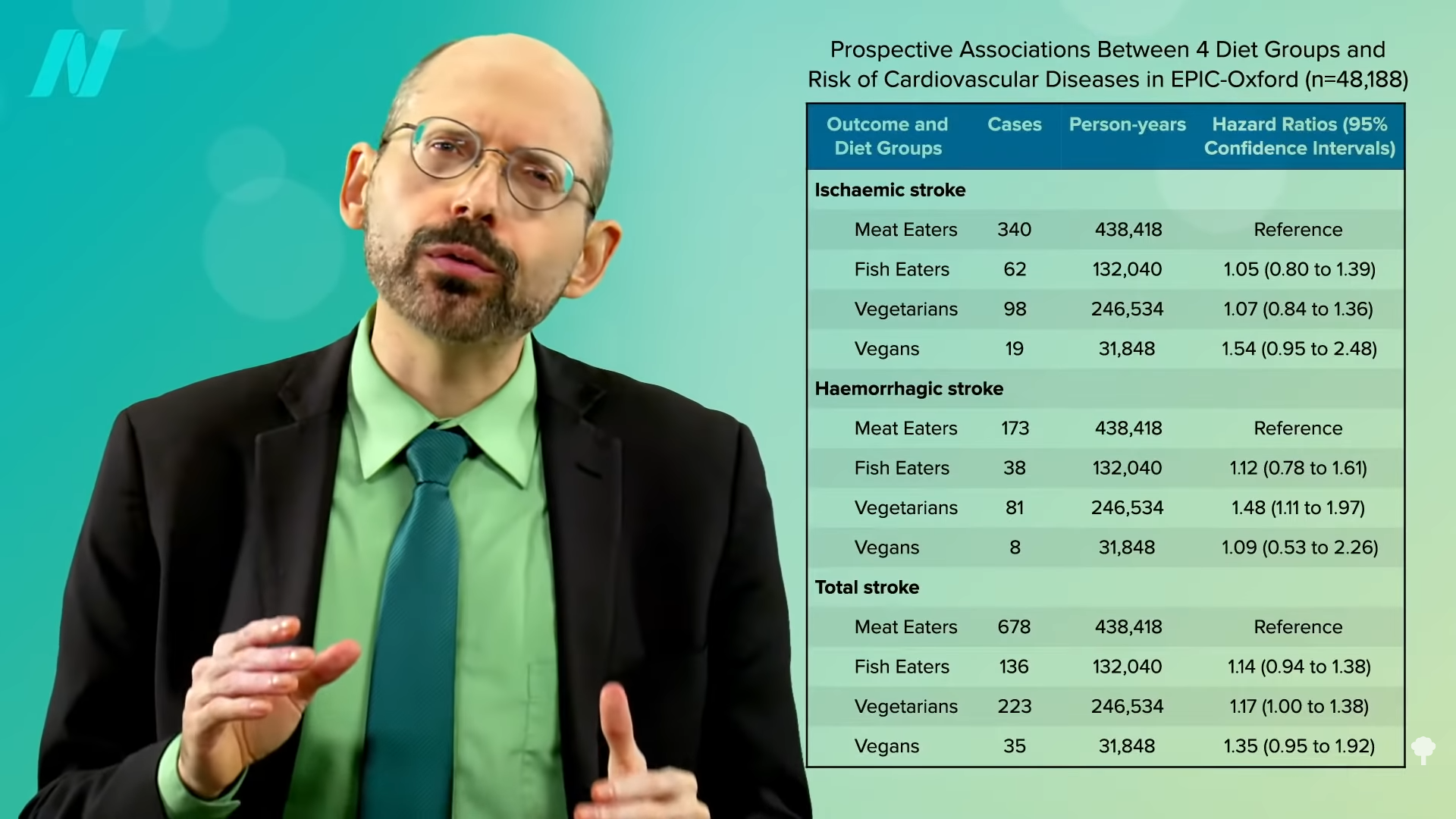

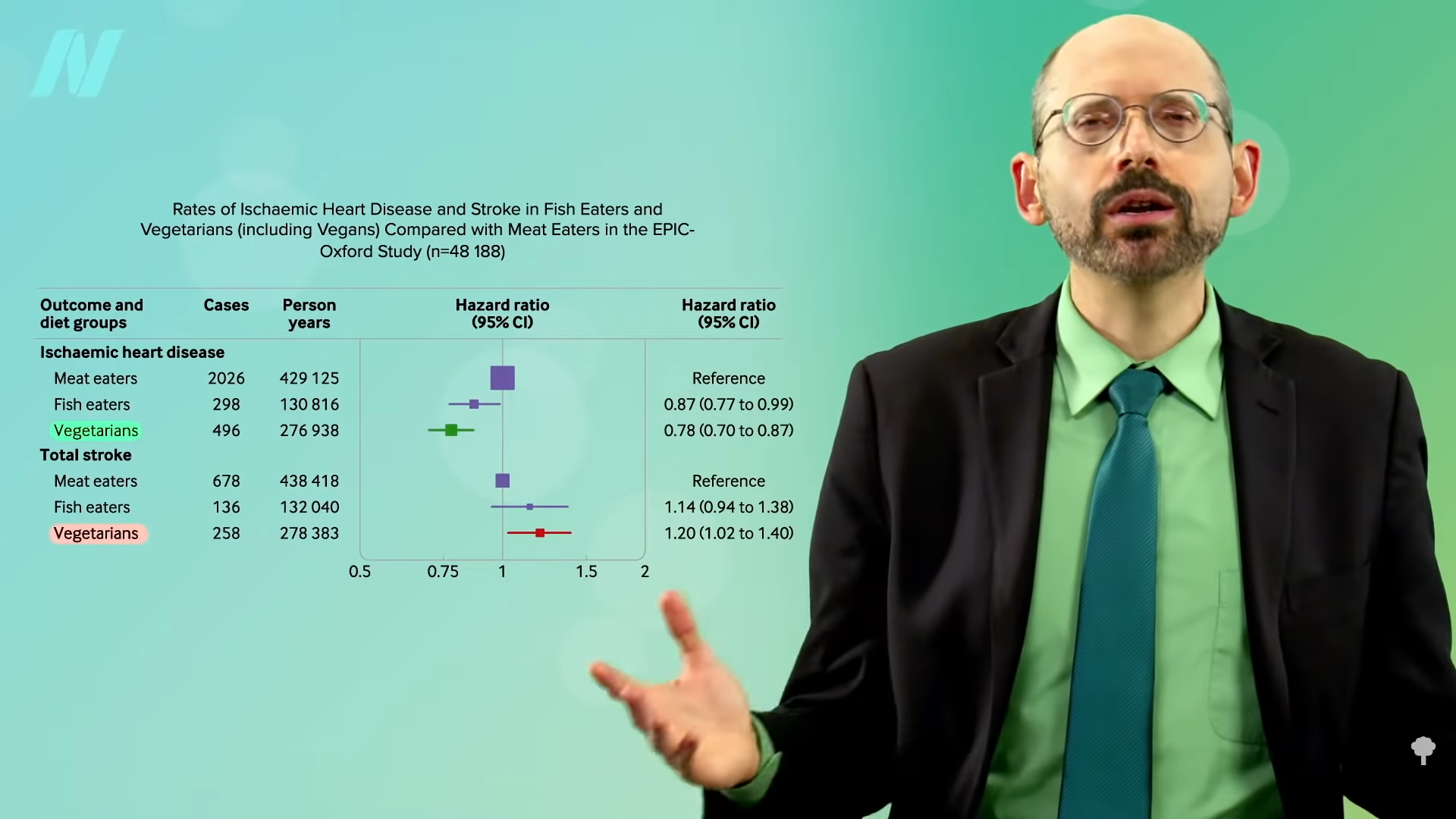

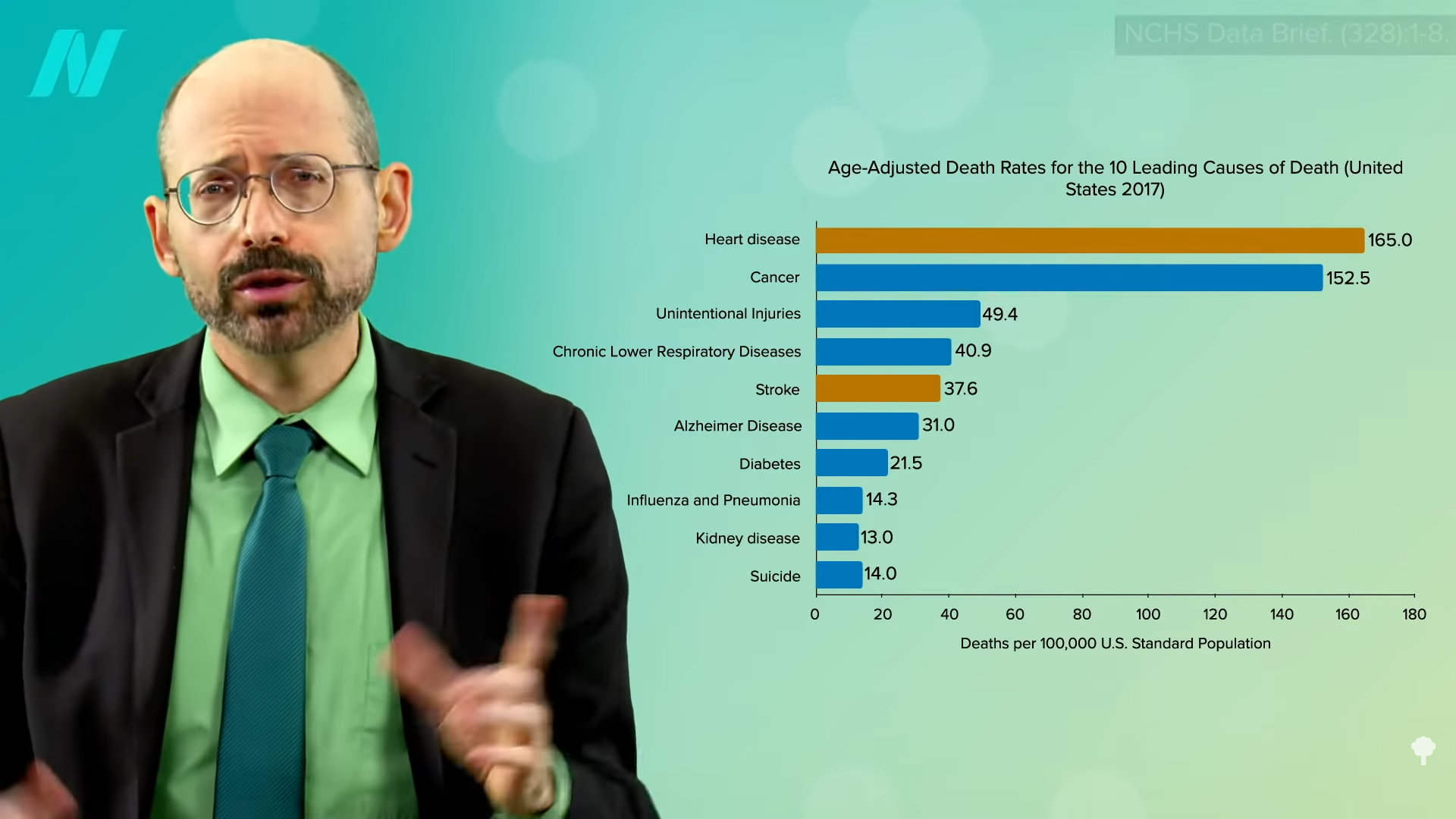

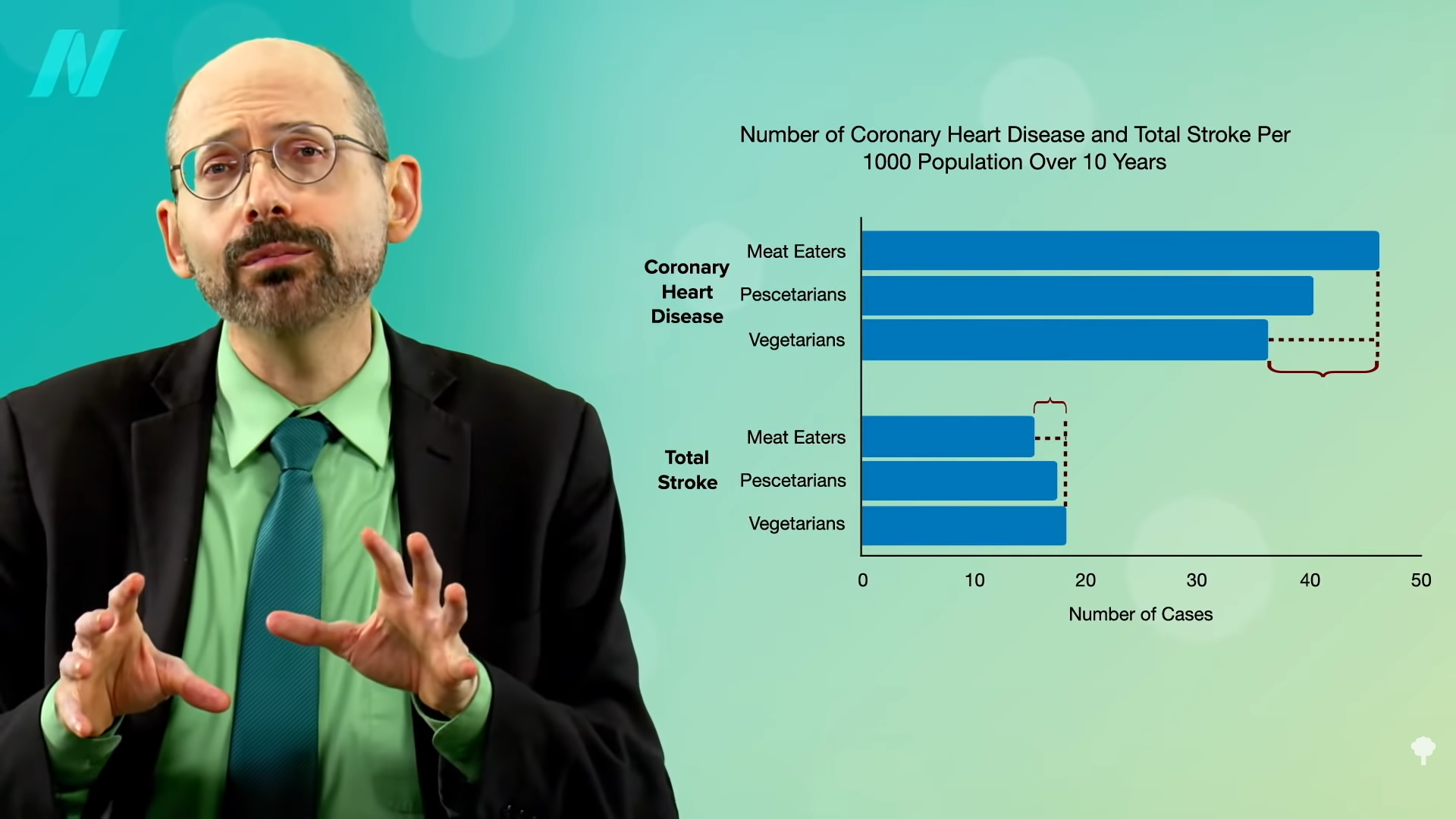

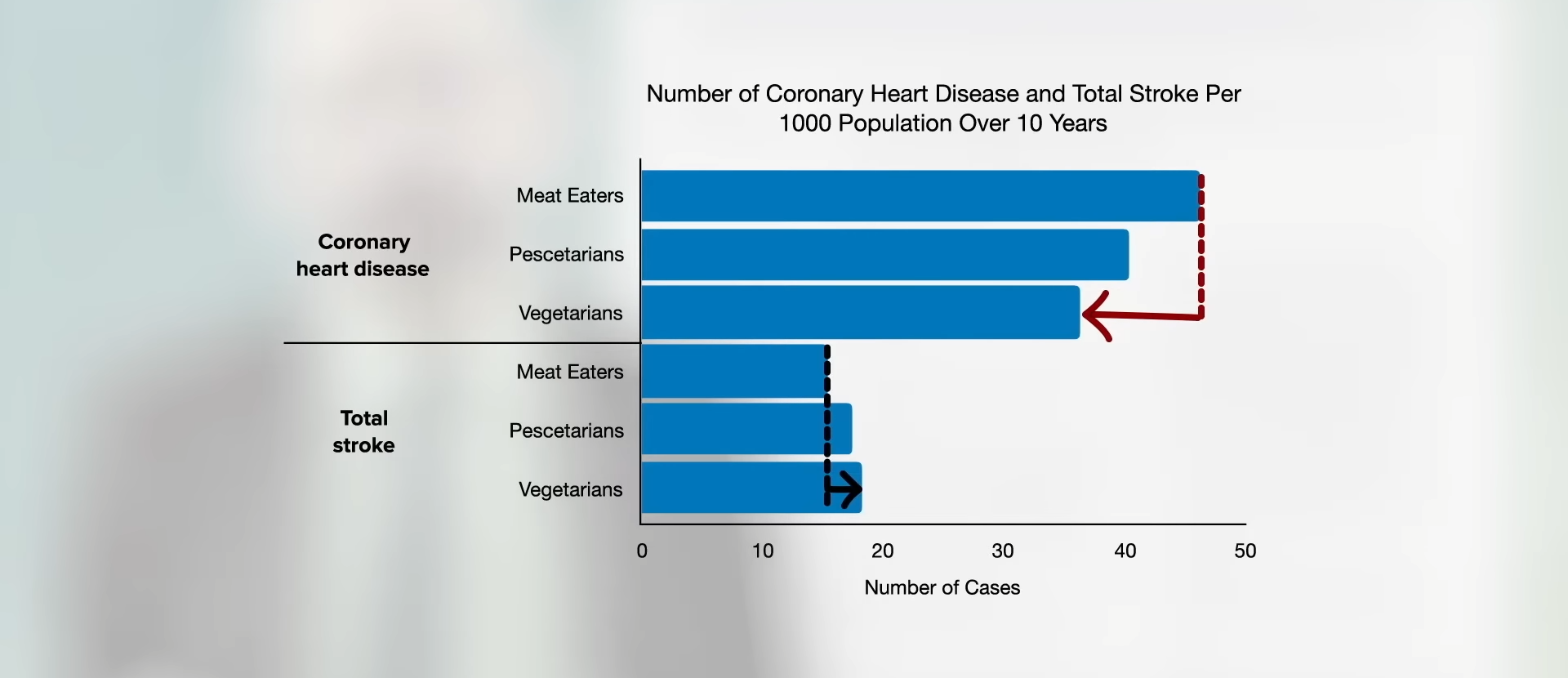

The reason I did this whole video series goes back to “Risks of Ischaemic Heart Disease and Stroke in Meat Eaters, Fish Eaters, and Vegetarians Over 18 Years of Follow-Up: Results from the Prospective EPIC-Oxford Study,” which found that, although the overall cardiovascular risk is lower in vegetarians and vegans combined, they appeared to be at slightly higher stroke risk, as you can see in the graph below and at 5:06 in my video.

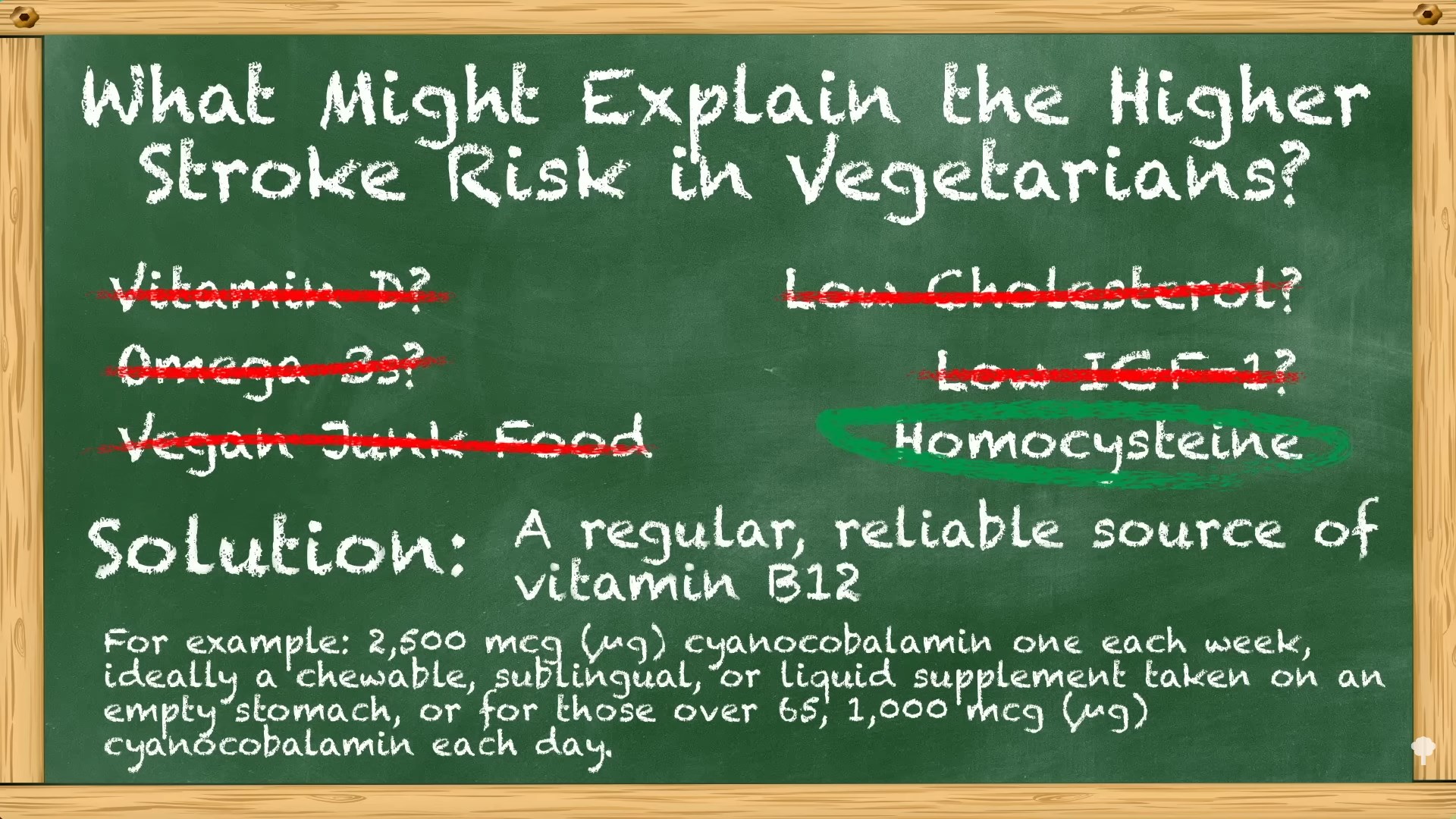

I went through a list of potential causes, as you can see at 5:11 and below, and arrived at elevated homocysteine. What’s the solution? A regular, reliable source of vitamin B12. The cheapest, easiest method that I personally use is one 2,500 mcg chewable tablet of cyanocobalamin, the most stable source of B12, once a week. (In fact, you can just use 2,000 mcg once a week.) And, again, a backup plan for those doing that but still having elevated homocysteine is an empirical trial of a single gram a day of creatine supplementation, which was shown to improve at least capillary blood flow in those who started out with high homocysteine levels.

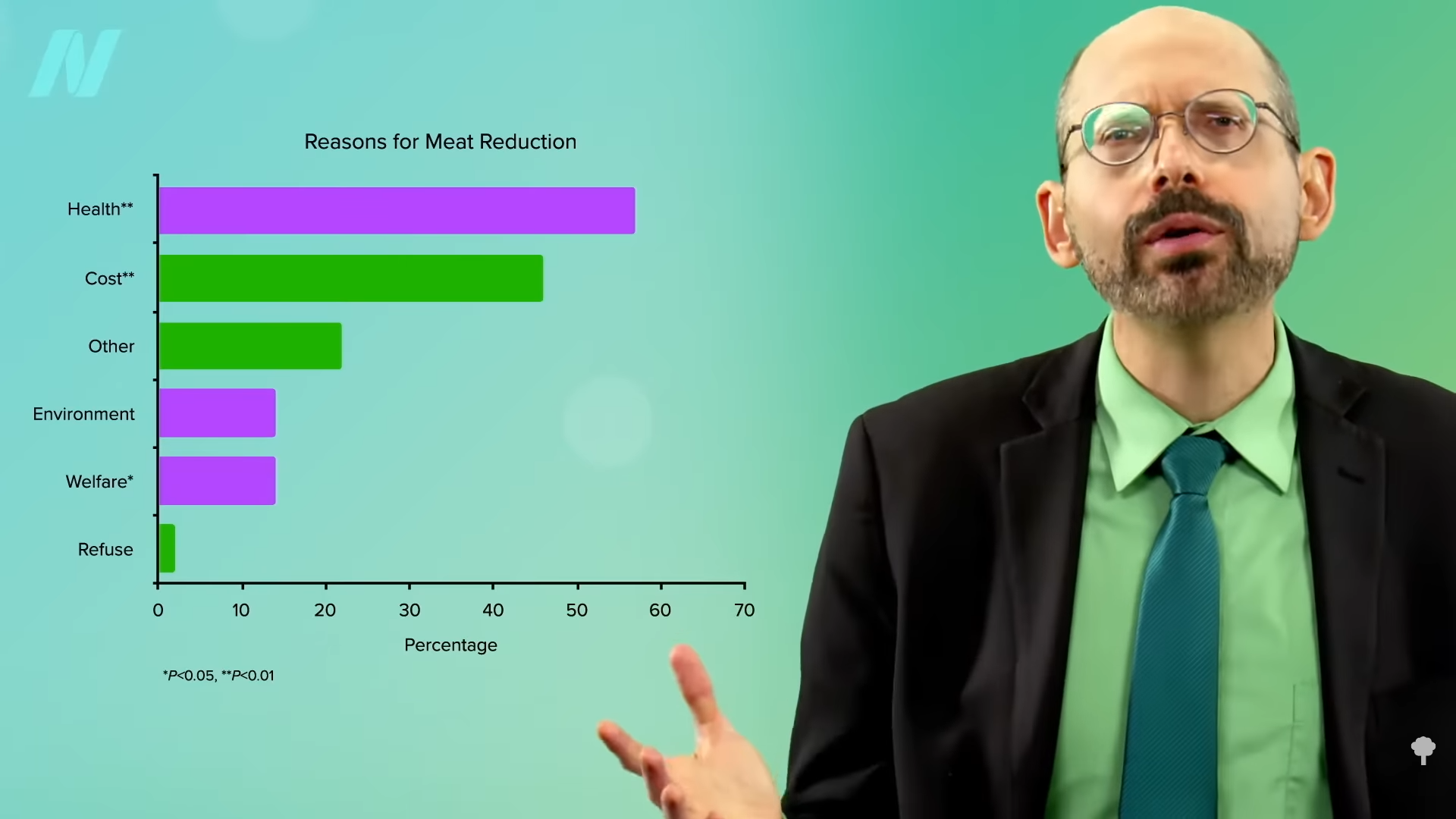

In sum, plant-based diets appear to “markedly reduce risk” for multiple leading killer diseases—heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and many common types of cancer—but “an increased risk for stroke may represent an ‘Achilles heel.’ Nonetheless, vegans have the potential to achieve a truly exceptional ‘healthspan’ if they face this problem forthrightly by restricting salt intake and taking other practical measures that promote cerebrovascular [brain artery] health…Nonetheless, these considerations do not justify nutritional nihilism. On balance, low-fat vegan diets offer such versatile protection for long-term health that they remain highly recommendable. Most likely, the optimal strategy is to adopt such a [plant-based] diet, along with additional measures—appropriate food choices, exercising training, judicious supplementation [of vitamin B12]—that will mitigate the associated stroke risk.” And try not to huff whipped cream charging canister gas. Leave the “whippets” alone.

This concludes my series on stroke risk. If you missed any of the other videos, see the related posts below.

I’m assuming that nearly everyone taking their B12 will have normal homocysteine levels, so these last two videos are just for the rare person who doesn’t. However, those on a healthy plant-based diet with elevated homocysteine levels despite taking sufficient vitamin B12 should consider taking a gram a day of contaminant-free creatine, which should be about a quarter teaspoon.

Where do you get contaminant-free creatine? Since regulations are so lax, you can’t rely on supplement manufacturers no matter what they say, so I would recommend going directly to the chemical suppliers that sell it to laboratories and guarantee a certain purity. Here are some examples (in alphabetical order) of some of the largest companies where you can get unadulterated creatine: Alfa Aesar, Fisher Scientific, Sigma-Aldrich, and TCI America.

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

Source link