If you were to name one of the more influential anime films to come out in the past few years, chances are Michael Sinterniklaas is responsible for its English dub.

Involved in the dubbing industry for decades, he has provided voice work for film and television series in addition to being at the helm of several prominent dubs as a casting and dialogue director. His most notable works in anime range from crafting the English dub for the Oscar-nominated Mirai to voicing in the dub for the global smash hit Your Name.

Past these feats, his company NYAV Post has handled the English dubs for a variety for projects for more than 20 years, ensuring they allow viewers to take in a given work with an interpretation that’s as close to the original creator’s intent as possible.

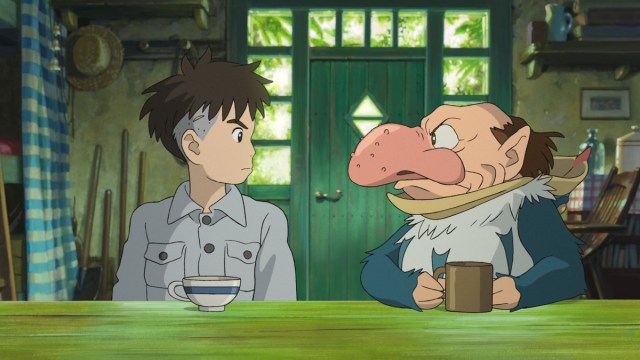

His latest directorial project, Studio Ghibli‘s The Boy and the Heron, has been of particular note. Not only is it stacked with a star-studded cast, but it is also made by the great Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli; and, rather sadly, it might be the acclaimed director’s final film.

We got the chance to sit down and speak with Sinterniklaas via Zoom about what it was like to direct The Boy and the Heron’s English dub, how he approaches dubbing, and the pressures that come with crafting the English dub for a film made by one of the world’s foremost animators and directors.

Keenan McCall: So obviously the Boy and the Heron has been very well received both critically and by fans, and even commercially. How does it feel to see the film performing this way, and especially because of the dub as most people are pointing out it’s one of the higher quality Ghibli dubs?

Michael Sinterniklaas: It’s actually extraordinary. When you do the work, you’re mostly in a black box, a padded room — literally — and it’s not like doing theater where you get to see an immediate response. So it’s lovely to see that people are taking notice of the work and I’m glad it’s being appreciated.

There’s a lot of consideration about not just dubbing — I’ve had my company NYAV Post now for, oh my god over 20 years — and we’ve always really focused on authenticity and grounding the dubs. Generally speaking, dubs are considered a second tier thing. I don’t disagree entirely, I think a lot of dubs are handled as second tier. It’s a deliverable spec and it’s a secondary language market and it’s got to be done, but not always artfully.

On (The Boy and the Heron), I thought it needed to serve very, very, very authentically Hayao Miyazaki’s original intention. And that I think is being recognized — that we didn’t put our scent on it, you know what I mean?

Keenan McCall: So a really big part of the hype around the movie and why there is particular interest around The Boy and the Hero is the fact that it could be Hayao Miyazaki’s final film. Did you feel that pressure when you were trying to craft the dub and direct the actors to put their all into their performances?

Michael Sinterniklaas: Absolutely. It’s tricky, it’s like going to the Olympics. You get nervous, but you’ve still got to do your best and you can’t let the nerves get in the way. If anything, that helped me dig in deeper and harder, work more weekends and late nights. I’m inclined to do that anyway with no semblance of work life balance, but in this case it was a whole other calling.

I think the last time I felt this way was when I’d worked on Ernest and Celestine. I recorded Lauren Bacall’s last ever performance, and at some point during the edit we were supposed to get her back in for another session and she just wasn’t really able to. When that happened, I remember thinking ‘this could be THE Lauren Bacall’s last ever performance. I need to make sure that every T is crossed and I is dotted and we can present it to (people) in the best way.”

It was like that, except for the entire movie. When I first saw (The Boy and the Heron), I remember halfway through, or a little bit later when you meet the Tower Master, going ‘Oh. I think this is his mic drop moment and he’s saying goodbye.’ And I remember getting really upset, and it meant even more to me.

But really, it manifested more as inspiration. Instead of just straight nerves and ‘Oh no, what do we do?’, it was like ‘No, we MUST do our best.’ You could probably make a whole other behind the scenes anime or Shonen Jump anime about doing your best, to do the best dub. We all felt like it was really important.

And then, at some point (during the dubbing process), he announced ‘Hey, I’m not done. I’m still going to do stuff’, and we were like ‘Oh. Wait, what? That’s great! I would rather you live forever and just keep releasing work.’ But then we were like ‘Maybe he just means shorts for the museum.’

But then, during production, Mark Chang — he’s my production manager in our New York Office — he said ‘Wait: When (the Tower Master) presents the blocks to Mahito, there are thirteen, and this is his twelfth movie.’ It’s crazy. On the one hand, this could be the last, so you care and you dig in. But then it’s better if it’s not, because I want more.

Keenan McCall: You’ve directed English Dubs for quite a few prominent anime directors and animators in the industry; namely, Makoto Shinkai and Mamoru Hosoda. Would you say there was any sort of different feel or different tones that affected how you crafted the dub for The Boy and the Heron vs. when you were crafting the dubs for Mirai and Your Name?

Michael Sinterniklaas: Absolutely. My background’s in classical theater, so I approach everything with a classical standard. There are a lot of fundamentals that I think are easy to overlook when you’re dubbing because it’s such a technical task. To really ground every moment and really understand where (the characters) are coming from, why are they saying this, all those things are fundamentals.

But going back to classical fundamentals, there’s a voice to Ibson, Bennett, Shakespeare, whatever. And in the case of Makoto Shinkai, he has a different flavor. All of his films leading up to Kimi no Na wa, Your Name, I think they had a melancholy, something slightly more dour. And then in the case of Your Name, he found this hope that married with it and had this really unique vibe all its own.

I really find myself needing to be moved by the original creator’s intent, but also need to find a way to ground every specific moment; but always in service of the spine of the intention of the creator.

In the case of Hayao Miyazaki, he’s revered as the greatest ever, so the tricky thing is he’s able to flow so freely from his unconscious mind that picking up what he’s laying down is so interpretive. So the challenge on this one was to let that inform what I’m doing without imprinting my own interpretation of it. To try and really telegraph what he’s really getting at. But we’ll never know definitively. There’s not going to be a DVD commentary where he’s telling you what everything means.

And that can be really tricky. When I did Mirai — the dub of which got Oscar nominated — I got to speak with Hosoda-san afterward. We had lunch, and I got to ask him some specifics. And he appreciated what I’d noticed about his movie, and in his case I’d found some moments in the animation that I served more completely in the vocal performances. He said he couldn’t get his actors to do certain things that we were able to do with ours.

My cue was seeing his intention in the picture, and these are all visual storytellers. My secret wish is that potentially we’re able to serve their truest intent, even on some moments they couldn’t do on their own. But in the case of Ghibli movies, Hayao Miyazaki’s potentially last film, it’s all about reading between the lines over and over and over again, and living with it and stewing in it and trying to convey all that.

Keenan McCall: What was your proudest moment during the dubbing process?

Michael Sinterniklaas: This kind of goes back to what I was just saying about serving the true intent, and not just what you see and hear. I think dubs can too often be a paint by numbers kind of task, and that’s never been my approach. I really think you need to take the story as a whole and justify the moments to serve that story again. Not just ‘they sound angry, they sound happy’. If you just hear the emotion and try to copy the emotion, that is literally the antithesis of the work. That’s being result-oriented and all the things that are like verboten in the world of acting and directing.

When we had Karen Fukuhara, who I think gives the sweetest performance in anything I think I’ve ever heard, she plays an important role. Because she’s fluent in Japanese, she heard what the original seiyuu was doing and then would give it back to us just like the original. And I remember thinking there’s a little bit more here. Not just to copy the sound, which she was doing impeccably, but to get at the underlying meaning of it. And so we had a sidebar halfway through, and she was able to make it a little bit more her own.

Also, the original seiyuu is I think a singer, so I was like ‘Well, since Karen has musical abilities but is primarily an actor, I don’t want to miss out on what she can bring to this character.’ And once we did that, something opened up. Because she plays a maternal figure, it really locked in. Even now when I watch it, she’s got a few lines in there that choke me up, and it’s like ‘I made these with her. Why do they still affect me like that?’.

I’m really proud of how she anchored that thing. And if I could talk to Hayao Miyazaki about anything, I’d like to ask him if we served his idea of this mother hero properly. Because I think she is both a hero and a mother in every sense of the word. In terms of her strength and her sacrifice and her love. The way she loves Mahito. To me it feels so appropriately Ghibli.

(Her dub) could have gone a very serviceable, perfect way, but I think it really leaps off the screen as its own thing, so I’m really proud of what Karen was able to bring to that.

Keenan McCall: A lot of people tend to say you almost need to watch both a Ghibli film in both the subbed version and the dubbed version whenever possible. Would you say that’s still the case with The Boy and the Heron? And what would you say are the pros of the sub and the pros of the dub?

Michael Sinterniklaas: I think it’s important, and I think it’s great, to watch it both ways. I think it’s important to see it in its original format of course. This is Hayao Miyazaki, he is Hayao Miyazaki. His name is literally an example of ‘It’s a Shakespeare, it’s a Mozart, it’s a Hayao Miyazaki.’ So see everything that he intended in his way.

I do think, however, that if you don’t speak Japanese, it’s a waste to have to read the bottom of the screen when there’s all this impossibly gorgeous museum-grade art flying by your face every second, every 24th of a second. I think you’re missing a lot of the film if you don’t do that.

The other thing, and this is really important I think when we talk about the value of dubs, is that a subtitle is also an interpretation of a translation. There’s translating (the original Japanese), and then you have to decide ‘does this word mean more this or more that? Well, I think it means more this.’ So you’re already going through one person’s filter, whoever the subtitler is. And then, they have to truncate the line so that it’s short enough that you can read it and then they can move on to the next card.

So I think that subtitles can often leave out a lot of key information. Sure, you get to hear the (original) performance, but if you don’t understand the nuance of the language, you’re missing so much information, even if you can hear the emotion of the performance. In that regard, I think dubs can more fully service a film than subtitles can if they’re done properly.

In our case, I think there are some incredible performances from incredible actors. I think we serve it better as a dub than not speaking Japanese and having to look at the bottom of the screen.

I think they both really have value, and people that I talk to have been running back to the theater to see it both ways and having different experiences. I do think it’s relevant that if you don’t speak that language, you need to hear it in a way that will connect with you emotionally. And I think that can do more depending on your relationship to the Japanese language.

But in this case, I would advise everyone to definitely see (The Boy and the Heron) both ways. I think the dub serves it very well. More than most of the other dubs in the pantheon of Ghibli dubs, it doesn’t deviate to entertain. It really holds true to the original intent, and that was our goal the entire way through. And hopefully, that’s what we pulled off.

Keenan McCall: Is there anything you’d like to add, or anything you’d like to pass along to anyone on the fence about seeing The Boy and the Heron in the dubbed version?

Michael Sinterniklaas: If they’re on the fence about seeing the dub, I would say… If you see it once, you understand that you probably need to see it again anyway. Seeing it in as many different ways as you can helps you receive this film which is an important film. It’s potentially his last film — which I pray that it’s not, because I selfishly want more — but it’s also his most personal, directly personal, film.

So if you care about the studio, if you care about Hayao Miyazaki, then you owe it to yourself to see (The Boy and the Heron) more than once and to see it every possible way you can; in different formats, different languages. I am in France, and I went to see the French dub of it so I could experience it yet again in another way. And I got something else out of it. It’s such a rich film that you’re not going to get it if you see it once. No one gets it seeing it once.

I talked to some of the top film critics in the industry, who I met at a press screening because while I was working on it, I needed to see it again, I needed to see it with other souls around me, I needed to see it big. So even though I’d already seen it a thousand times, I needed to see it in a different way. And I got something out of it. But all these critics were like ‘Yeah, I really understand this creator and this studio, but I don’t understand this movie yet. I need to see it again.’ So I encourage everyone to go on this journey.

The Boy and The Heron is currently screening in theaters worldwide.

Keenan McCall

Source link