[ad_1]

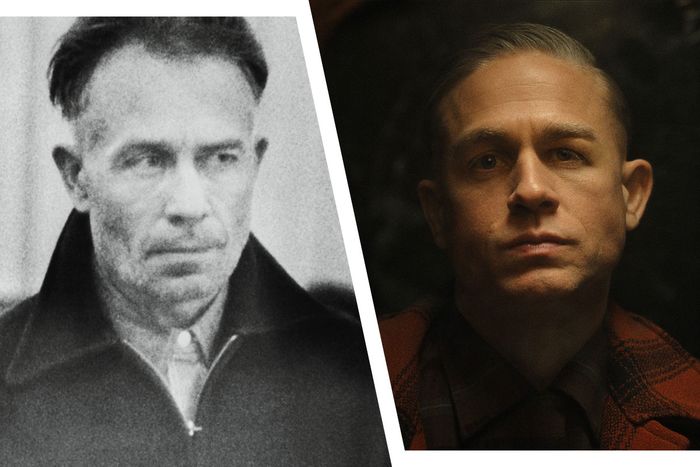

The third installment of Monster justifies its various imaginings through constant reminders that Ed’s (Charlie Hunnam) grip on reality that is tenuous at best.

Photo: Netflix

Ryan Murphy “based on a true story” adaptations are known for having a flexible relationship with the truth. That willingness to play fast and loose with history gained new momentumb in the Monster series, the first two seasons of which made questionable diversions from the life of Jeffrey Dahmer and the saga of the Menendez brothers. But in an interesting twist, the new third installment, The Ed Gein Story, embeds the idea of differing versions of the truth into the season’s narrative. After all, Ed Gein inspired legendary fictional villains like Norman Bates (Psycho), Leatherface (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre), and Buffalo Bill (The Silence of the Lambs), so not only does Monster offer deeply fictionalized versions of Gein’s crimes, it moves its adaptive tendrils outward to explore how his monstrous actions rippled through pop culture.

That approach opens up all sorts of new avenues to diverge from the historical record. Murphy’s Monster co-creator Ian Brennan, who writes all eight episodes, clearly savors taking kernels of truth and turning them into batches of popcorn this season. In doing so, he insulates himself against charges of gross extrapolation through constant reminders that Ed’s grip on reality is tenuous at best. Think something didn’t happen quite that way? Well, maybe Ed thinks it did. (Although this doesn’t explain some of what this season does to the production of Psycho.) There are details in all eight episodes that are based on verifiable facts, but anything unverifiable, anything that might have happened, even in Ed’s mind, is fair game for Monster, too. Get the shovels, we’re digging for the truth buried within Monster’s grisly fantasia of the Ed Gein story.

Heavy spoilers follow.

The “Butcher of Plainfield” became one of history’s most notable murderers not because he killed at least two women but because of what he did with their bodies, and others he dug up at the local cemetery. The list of items that authorities found when his house was raided in 1957 is pure nightmare fuel, including a wastebasket made of human skin, bowls made from skulls, a belt made of nipples, a lampshade created from a human face, and nine vulvas in a shoebox. Most of these body parts were obtained from the cemetery, but also from two women Gein killed: Mary Hogan and Bernice Worden. They found Mary’s face, which Ed had been using as a mask, and Bernice’s entire head. Gruesome, to be sure, and Monster incorporates all of those gnarly details and more.

Monster is pretty consistent with the details of the atrocities Gein confessed to, including hanging Bernice’s body up in a shed, shooting Mary Hogan, and grave-robbing from the cemetery. However, he was only suspected of other crimes that the show presents as fact, including the disappearance of a young woman named Evelyn Hartley; a pair of missing hunters named Victor Travis and Raymond Burgess that Monster presents as victims of a chainsaw murder that would inspire Leatherface; and even the death of Ed’s brother Henry, which the authorities ruled as a product of asphyxiation despite finding bruising on his head that the show portrays as Ed’s first assault.

And what about all that nasty mother stuff? According to a 1957 psychological report printed in The Ed Gein File: A Psycho’s Confession and Case Documents, “After the death of his mother … his emotional needs influenced him to attempt the re-creation of his mother by using the parts of bodies from other graves.” So that part aligns pretty closely with Monster’s depiction of Ed’s motivations, although it should be noted that experts on the case are unsure about the extent of Gein’s necrophilia, with Gein claiming that he didn’t have sex with the bodies he exhumed because of the smell. So that truly upsetting scene in episode five is supposition, depending on if you believe a man who did what Gein did had boundaries.

Monster arguably saves its most unconfirmable flights of fancy for Adeline Watkins, the alleged on-and-off girlfriend of Ed Gein for over 20 years. Maybe. Probably not. The truth is that almost nothing is known about Watkins other than she knew Gein and once said in an interview that they had briefly dated at different times in her life. But she later recanted those claims, saying that her original quotes were blown out of proportion and that she’d never been inside Gein’s house, they only went to the movies a few times.

The Monster version of Adeline Watkins is not that at all, portrayed more as a Lady Macbeth urging on Ed’s monstrous ways. The fifth episode is particularly remarkable, implying that Adeline not only attacked someone in New York after a meeting with the infamous crime scene photographer Weegee (played by Elliott Gould) but that her mother (Robin Weigert) told her that she threw herself down the stairs multiple times to kill Adeline in utero. Could that have happened? Theoretically, and that’s all Monster needs to run with something.

The idea that Watkins was an enabler of Gein’s murders and subsequent desecrations could be read merely as a part of the show’s aggressive and admitted mingling of fiction and reality. After all, Watkins also plays a Marion Crane figure in the show, introduced with Ed peeping on her a la Norman Bates, and later envisioned being brutally murdered in a shower while audiences watch a version of Psycho that never existed. In the end, she serves multiple functions on the show as an object of obsession, a partner in crime, a sociopath herself, and a necrophiliac’s girlfriend. That the real Adeline was likely none of those things is fitting for a show about how truth becomes legend, and vice versa.

Photo: Netflix

We don’t see much of Ed’s mother Augusta in Monster, and what we do see and hear is often filtered through Gein’s visions and hallucinations. Like a lot of people in this case, not much is known about Augusta Gein other than she married George and had two sons, Ed and Henry. She was reportedly very religious, which is captured on the show in her railings against loose women and the immorality of the world around her. George died in 1940 and Henry in 1944, leaving Ed alone with Augusta, which is when his mental decline began to accelerate.

Again, Monster blends truth and fiction from the very beginning. Believe it or not, the detail about Ed and Augusta seeing a man abusing a dog seems to be true, at least according to Gein’s account, although she didn’t drop dead on the scene as the show depicts. What Brennan does capture through Augusta is Ed’s obsession with her, reflecting what expert Harold Schechter wrote in his 1989 book Deviant about how she was “his only friend and one true love,” and that after she died, “He was absolutely alone in the world.”

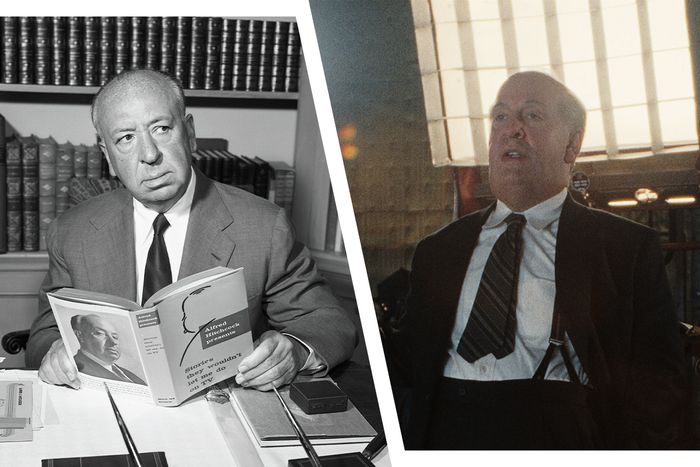

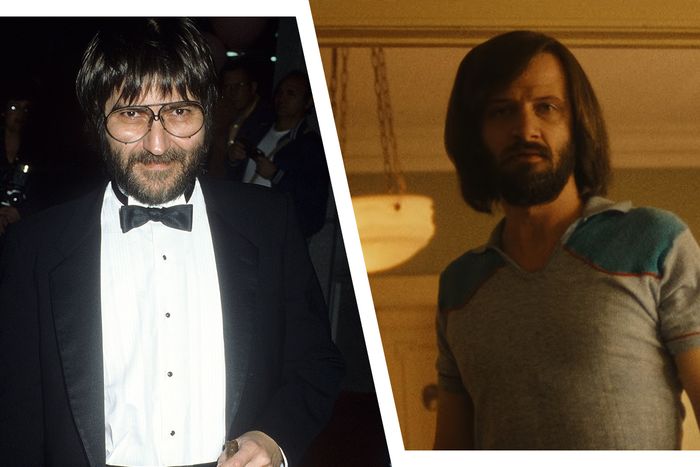

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Paul W. Bailey/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images, Netflix

In one of several sections of the show that seeks to capture the influence of Ed Gein on pop culture, Brennan imagines the Master of Suspense’s obsession with the moral boundaries crossed by the man who would inspire Norman Bates. Of course, Psycho was based on a novel of the same name by Robert Bloch, which was loosely inspired by Gein. A review of the book caught the attention of Peggy Robertson, Hitch’s assistant, and the filmmaker forwent his director’s fee and lowered the budget to get it approved by Paramount distributors. Much has been written about the production of Psycho, including how it radically deviates from the book — Marion is barely a character in the source and Bates doesn’t look like Anthony Perkins — but Hitchcock being as obsessed by Gein’s horrific tendencies as he is in Monster is a new idea, one largely imagined.

The show’s bending of reality fully breaks in episode two as we see Hitch watching a tumultuous screening of Psycho, complete with vomiting and fainting audience members, and even get a re-creation of the shower scene with Hunnam’s Ed and Son’s Adeline in the Norman and Marion roles. Anyone who’s seen the actual movie knows the nudity and graphic violence of the Monster version doesn’t match up with the source; it’s just one more example of how all the material here about the production of Psycho is exaggerated for effect.

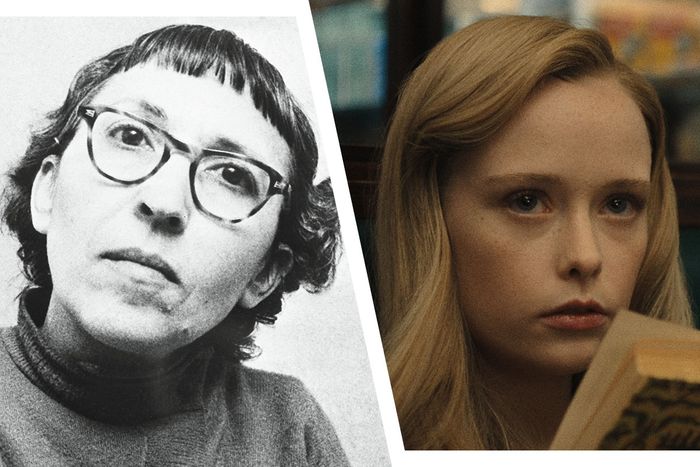

Photo: Vulture; Photos: Pierre Vauthey/Sygma via Getty Images, Netflix

In a show full of oversized versions of real-life people, Alma Reville is surprisingly subtle, but also remarkably underdeveloped, especially given the talent of the actress cast to play her. The real Reville married Alfred Hitchcock in 1926 and they remained partners until his death in 1980. Her work with Hitch is well-documented, including collaborating on some of his best scripts, but Monster really just uses her as a judgmental sounding board for Alfred, there to shake her head after Psycho typecasts him into a new genre called “sex horror.” She’s just there to look concerned at Alfred and say things like “You have other stories to tell.”

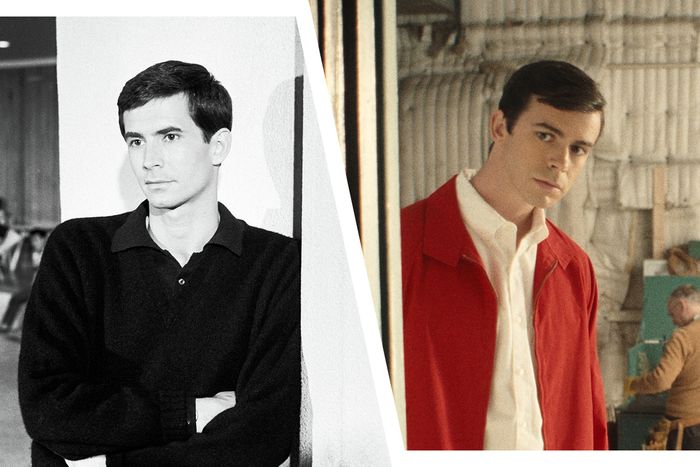

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Reporters Associes/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images, Netflix

Hitchcock’s Psycho star doesn’t get much to do in Monster, either, although the way the show connects him to Gein is significantly more insulting to the actor’s legacy than what it does with Alfred and Alma: A show about a cross-dressing psychopath introduces the actor who would play Norman Bates cross-dressing with his boyfriend. Ugh. In a later scene, Bates gets a blowjob from a boyfriend while watching himself on the big screen in Psycho. There isn’t really enough to hold onto here in terms of fiction vs. reality because Monster is only interested in the fact that Perkins felt he had to remain closeted to keep his fame, and that tenuous connection to Gein’s behavior behind closed doors isn’t just shallow, it’s pretty gross.

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images, Netflix

The fourth episode of Monster suggests that a young Tobe Hooper heard about Ed Gein from his father at the dinner table, incorporating that into his vision of the 1974 horror masterpiece The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. It also imagines an adult Hooper sparking to the idea at a Montgomery Ward department store when he sees a chainsaw and fantasizes about using it to carve through a holiday shopping line. He then incorporates the body suit stories about Gein into his vision of Leatherface on the set of TCM.

There’s a tiny bit of truth hiding in Monster’s imaginings about Hooper. Yes, the filmmaker said that elements of Gein’s crimes inspired elements of TCM, but it’s a film about a lot more than the Plainfield Ghoul, including the proliferation of misinformation and the Vietnam War, which the episode nods to as well. Hooper wanted to tell a true story that wasn’t really true, sort of like what Monster does.

Photo: Netflix

A 58-year-old Plainfield hardware store owner, Bernice Worden disappeared in November 1957. Her son, Deputy Sheriff Frank Worden, led the investigation after finding blood stains on the floor, discovering that Gein had been seen in the store the night before she disappeared. This led to the investigation of Gein’s farm that unearthed his atrocities, including Worden’s body being decapitated, flayed, and hung in his shed. Both Mary Hogan and Bernice Worden were roughly similar in age, appearance, and background Augusta Gein, which is likely why Ed killed them.

Monster devotes a scene to an imaginary encounter with Ilse Koch that inspires Ed to kill Mary (played by Rondi Reed), but the show really goes nuts with its version of Bernice, going so far as to imagine a torrid sex scene between the two in which Ed wears women’s clothing before the two fornicate. Monster uses this encounter to thematically tie Ed’s murder of Bernice to his own confused sexuality and mommy issues, but underlines the unreality of the situation via the green blood that seeps from Bernice’s head after he shoots her in the hardware store.

Photo: Netflix

In October 1953, 14-year-old Evelyn Hartley went missing in La Crosse County, Wisconsin, after she had been hired to babysit the 20-month-old daughter of a man named Viggo Rasmussen, and was never seen again. A local man claimed to have seen two men in a vehicle that night not far from the Rasmussen house, and there were strange details about the house, including every room being locked and a window missing a screen with a stepladder leading to it, but Evelyn’s body was never found. When he was arrested, Gein was asked about the case because he lived not far from the house, but no trace of her was found in the Gein residence, and, well, he wasn’t exactly big on hiding body parts, which was likely one of the reasons that the authorities cleared Gein of any involvement with this one (as well as the disappearance of 8-year-old Georgia Weckler, also insinuated on the show).

In the third episode, Monster posits that Ed tried to get a babysitter job to prove he could be a father with Adeline, and that said job was “stolen” by Evelyn Hartley. So what does Ed do? He stalks and kidnaps her, trying her up in his basement and yelling at her about how he was somehow going to pay for a wedding with a “babysittin’ job.” Then he introduces her to “mother” before bashing her in the head with a hammer. In a series with a lot of torturously gross scenes, it’s one of the grossest.

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images, Netflix

A German war criminal who was married to the commandant of Buchenwald during World War II, Ilse Koch is deserving of a Monster season of her own. In the show, Ed is inspired by a comic book about Koch titled The Bitch of Buchenwald, given to him by Adeline, suggesting that her sadistic treatment of Jews during the Holocaust led to Gein’s house of horrors in Wisconsin. Most of the show’s version of Koch comes from witness testimony during her 1947 US military commission court trial at Dachau, where she was accused of many of the atrocities seen on the show. That includes turning skin into lampshades, something that two inmates alleged to have seen happen but was never proven; when Buchenwald was raided, items made from human skin were found, but the direct connection to Koch could never be established.

Monster’s visions of Ilse Koch are freed from the historical record because they’re merely what Ed sees in his head after reading the comic book. Whether or not The Bitch of Buchenwald did what is reenacted on the show isn’t relevant, because her activities are placed in the context of a comic book that exaggerates history to make a point — just like Monster does. That is until the seventh episode, in which Ed contacts an imprisoned Ilse over ham radio just before she kills herself. Koch did indeed die by suicide in prison, but did she really speak to Gein beforehand? Of course not, but the walls of reality have crumbled so completely by this point in Monster that we’re in and out of Ed’s hallucinating mind. Maybe we were all along.

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images, Netflix

As an institutionalized Ed starts to examine what’s behind his cross-dressing ways in the seventh episode, he comes across a recording of “I Enjoy Being a Girl” by Christine Jorgensen, dancing and singing along in his bra and panties. One of the first people widely known to have had a sex reassignment surgery, Christine Jorgensen became a celebrity on the New York scene in the early 1950s. In 1957, she saw Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Flower Drum Song, becoming enchanted by the track that captivates Ed and making it her own.

In the “Ham Radio” hallucination episode of Monster, Gein “calls” Jorgensen to ask her about why he feels disconnected from his “trouser snake.” As he tells his imaginary Christine about his mother abusing him after catching him masturbating, we hear her voice coming from the mouth of his therapist, the person he’s really speaking with, and flash to the iconic scene in The Silence of the Lambs when Buffalo Bill wears his woman suit, drawing a line between Ed’s proclivities and that masterful film. But imaginary though she may be, Christine gives Ed a much-needed reality check when she makes it clear that his attempt to use her experience to explain his immoral behavior won’t fly. “I don’t think you and I are alike at all,” she says. “The transexual is rarely the perpetrator of violence, Mr. Gein. We are far more likely to be the victims of violence.”

Photo: Netflix

In the truly bonkers finale of Monster: The Ed Gein Story, Netflix gets as close to a third season of Mindhunter as there will likely ever be. Happy Anderson, who played serial killer Jerry Brudos on that acclaimed show, returns as the Shoe Fetish Slayer Jerry Brudos, talking to characters clearly meant to be Holden Ford and Bill Tench, though they’re named John Douglas and Robert Ressler, about how he was inspired by Gein. They then go back to their basement office and talk about the case with a woman modeled after Wendy Carr.

After that WTF opening, the finale works hard to push the idea that Gein influenced numerous other serial killers. Anderson’s Brudos says, “I chopped my share of bodies once I heard about the fella in Wisconsin that did it.” The infamous Richard Speck (Tobias Jelinek) talks about his titties and sends a letter to his beloved Ed, which Gein then uses, Hannibal Lecter-style, to lead the authorities to catch Ted Bundy. And then, in one of the most OMG things that’s ever appeared on Netflix, a near-death Gein has a vision of serial killers thanking him for how he inspired them, including Brudos, Speck, Charlie Manson, Ed Kemper, and more. After a bizarre goodbye with Adeline that feels half-imaginary itself, he goes back to the hall of monsters in his mind and ascends the Psycho staircase to his waiting mother as Yes’s “Owner of a Lonely Heart” plays on the soundtrack. And thus Monster goes out having fully intertwined reality, fiction, and legacy into one nutty vision that it is almost impossible to believe exists.

[ad_2]

Brian Tallerico

Source link