by TeachThought Staff

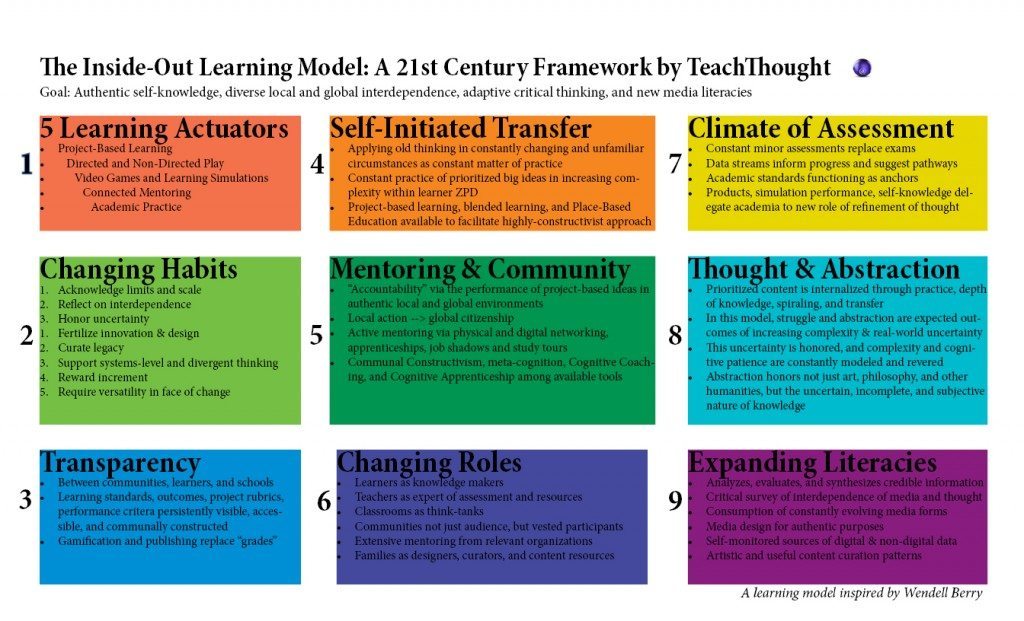

You want to teach with what’s been proven to work.

That makes sense. In the ‘data era’ of education that’s mean research-based instructional strategies to drive data-based teaching, and while there’s a lot to consider here we’d love to explore more deeply, for now we’re just going to take a look at the instructional strategies themselves.

See also Examples of Learning Technology

But upside to sharing this information as a post is that it can act a starting point to research the above, which is why we’ve tried to include links, related content, and suggested reading for many of the strategies, and are trying to add citations for all of them that reference the original study that demonstrated that strategy’s effectiveness. (This is an ongoing process.)

How should you use a list like this? In 6 Questions Hattie Didn’t Ask, Terry Heick wondered the same.

“In lieu of any problems, this much data has to be useful. Right? Maybe. But it might be that so much effort is required to localize and recalibrate it a specific context, that’s it’s just not–especially when it keeps schools and districts from becoming ‘researchers’ on their own terms, leaning instead on Hattie’s list. Imagine ‘PDs’ where this book has been tossed down in the middle of every table in the library and teachers are told to ‘come up with lessons’ that use those strategies that appear in the ‘top 10.’ Then, on walk-throughs for the next month, teachers are constantly asked about ‘reciprocal teaching’ (.74 ES after all). If you consider the analogy of a restaurant, Hattie’s book is like a big book of cooking practices that have been shown to be effective within certain contexts: Use of Microwave (.11 ES) Chefs Academic Training (.23 ES), Use of Fresh Ingredients (.98). The problem is, without the macro-picture of instructional design, they are simply contextual-less, singular items.”

In short, these instructional strategies have been demonstrated to, in at least one study, be ‘effective.’ As implied above, it’s not that simple–and it doesn’t mean it will work well in your next lesson. But as a place to begin taking a closer look at what seems to work–and more importantly how and why it works–feel free to begin your exploring with the list below.

These strategies are research-based and tuned for 8th-grade classrooms. Each card includes a short description, citations, and two “Try it” moves you can use tomorrow.

Planning & Clarity

Setting Goals & Success Criteria

Make learning goals visible and pair them with concrete success criteria students can self-check.

Evidence:

Locke & Latham (2002) ·

REL Midwest (ERIC open-access, 2018)

- Co-write 2–4 “I can…” criteria; reference them at launch, mid-lesson, and exit.

- Run a 1-minute “criteria check” where students highlight where their work meets/doesn’t.

Teacher Clarity

Organize explanations, examples, and lesson flow so students can follow and act on them.

Evidence:

Fendick (1990) ·

Titsworth et al. (ERIC, 2015)

- Open with a 30-second “map” (Goal → Steps → Proof of learning).

- Model one worked example + one non-example before guided practice.

Related: TeachThought: Assessment

Cues, Questions & Advance Organizers

Activate prior knowledge and preview the structure so new content has hooks.

Evidence:

Mayer (1979) ·

ERIC (1979)

- Start with a 90-second concept map (big nodes only) before instruction.

- Pose 2 essential questions; revisit mid-lesson and at exit.

Scaffolding Instruction

Provide temporary supports (prompts, hints, partial solutions) and fade them as competence grows.

Evidence:

Wood, Bruner & Ross (1976) ·

ERIC (2002 overview)

- Give a 4-step checklist; remove one step each subsequent attempt.

- Sentence starters for draft 1 only; original phrasing required on draft 2.

High Expectations (Warm Demanding)

Communicate belief in every student’s ability and provide credible pathways to meet the bar.

Evidence:

Rosenthal & Jacobson (1968) ·

ERIC (1968)

- Set a visible quality bar (exemplar + single rubric row) and require one revision for all.

- Use growth-focused feedback scripts (“Next step: add a counterexample in ¶2”).

Plan With the Nine Research-Based Categories

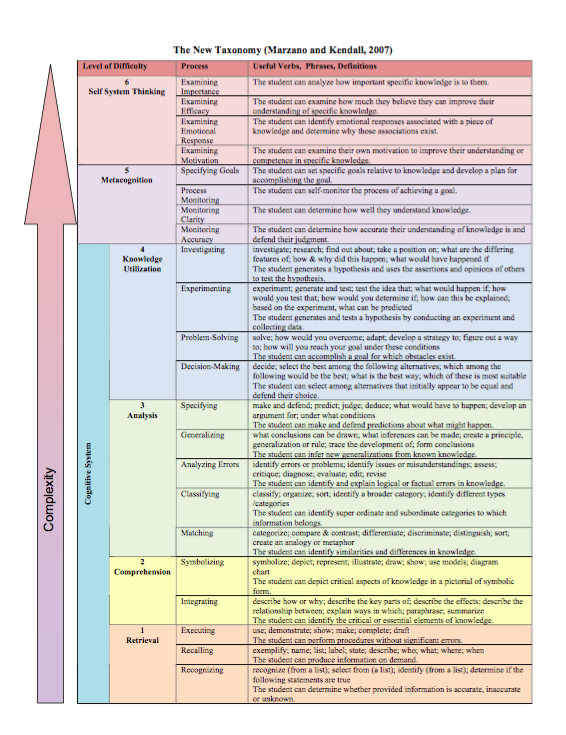

Use Marzano’s nine categories to balance clarity, processing, practice, feedback, and transfer across units.

Evidence:

Marzano et al. (2001) ·

McREL (ERIC-indexed report)

- Tag each lesson segment to a category; add one missing category this week.

- Use a PLC template with nine checkboxes during unit planning.

Instruction & Modeling

Direct / Explicit Instruction (Rosenshine)

Teach in small steps with clear models, guided practice, frequent CFUs, and cumulative review before independence.

Evidence:

Rosenshine (2012) ·

ERIC (2012)

- Chunk new material into 5-minute bursts with a quick CFU after each.

- “You do a little / I peek a lot”: circulate and prompt during guided practice.

Related: TeachThought: Project-Based Learning

Modeling with Worked Examples

Show complete exemplars (and non-examples), then fade to completion problems and full independence.

Evidence:

Sweller et al. (2006) ·

ERIC (2006)

- Model one full problem; then assign a completion problem with the last step blank.

- Show a non-example; ask students to spot and fix the error.

Guided Practice (Opportunities to Practice)

Provide structured practice with immediate feedback before asking for independent performance.

Evidence:

Rosenshine (2012) ·

ERIC (2012)

- Run “I do → We do → You do” across a single period; pause for quick corrections.

- Use mini-whiteboards for whole-class guided checks and fast feedback.

Deliberate Practice & Spacing

Short, frequent practice with feedback, distributed over time and interleaved with prior content.

Evidence:

Cepeda et al. (2008) ·

ERIC (2012 overview)

- Turn a 20-minute block into two 8-minute bursts with a 2-minute retrieval check.

- Open with 3 spaced “warm-backs” from last week before new content.

Nonlinguistic Representations (Dual Coding)

Pair words with visuals (diagrams, timelines, gestures) so verbal and image traces reinforce each other.

Evidence:

Clark & Paivio (1991) ·

ERIC (2019)

- Require a 30–60s sketch for each new concept.

- Introduce an icon/gesture for key terms and cue students to use them.

Processing & Meaning-Making

Cooperative Learning

Structured peer interaction with shared goals and individual accountability.

Evidence:

Johnson & Johnson (1989) ·

ERIC (1994)

- Assign roles (facilitator, checker, summarizer) + an individual exit slip.

- Give a 60-second “quiet think” before talk so every student brings an idea.

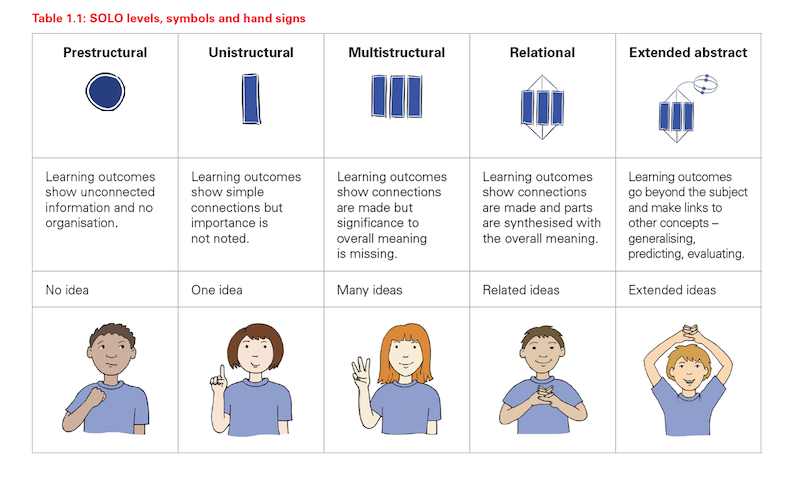

Concept Mapping

Externalize relationships between ideas via labeled connections and hierarchies.

Evidence:

Novak & Gowin (1984) ·

ERIC (2018)

- Give 10 terms + verb list (causes, leads to, contrasts with); require labeled arrows.

- Students write a 2-sentence “pathway” using three nodes.

Reciprocal Teaching

Rotate roles (clarify, question, predict, summarize) to build comprehension through coached dialogue.

Evidence:

Palincsar & Brown (1984) ·

ERIC (1992)

- Run a 10-minute rotation on a short text; swap roles mid-reading.

- Provide role cards; require a 3-sentence group summary at the end.

Related: TeachThought: Questioning & Inquiry

Identifying Similarities & Differences

Compare, classify, or analogize concepts to expose structure and distinctions.

Evidence:

Marzano et al. (2001) ·

ERIC (2010)

- Quick 2×2 matrix (feature A/B vs present/absent) to classify examples.

- One metaphor/analogy per pair capturing the key difference.

Summarizing & Note-Taking

Distill essential ideas concisely; generative processing supports retention and comprehension.

Evidence:

Hidi & Anderson (1986) ·

ERIC (1999)

- Impose a 12-word summary limit, then expand to 40 words with one quotation.

- Use Cornell notes: add one test question per section before leaving.

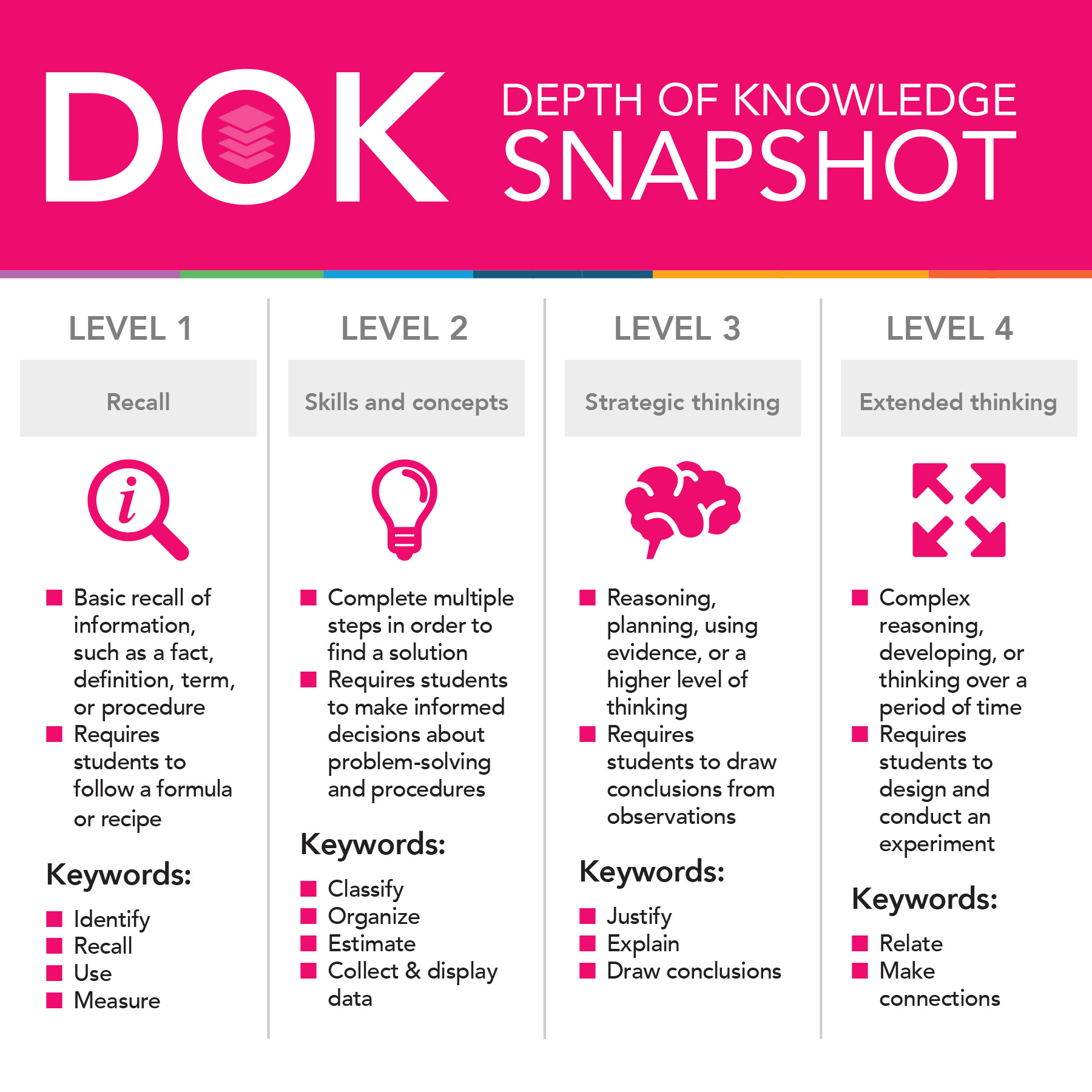

Generating & Testing Hypotheses

Make predictions, test them, and revise thinking based on evidence.

Evidence:

Marzano et al. (2001) ·

ERIC (2013)

- Students write a specific prediction and design a 3-step mini-test to check it.

- Require a “claim–evidence–revision” sentence after results.

Comparison Matrix (Protocol)

Use a criteria-by-item grid so students weigh alternatives and justify choices.

Evidence:

Marzano et al. (2001) ·

McREL (ERIC-indexed)

- Provide a 3×3 matrix with criteria in rows; students rate/justify each item.

- End with a forced choice: which is best for X and why (cite two criteria)?

Anticipation Guides

Use brief agree/disagree statements to surface preconceptions and set a purpose for reading.

Evidence:

Buehl (2001) ·

ERIC (2015)

- Create 4 statements tied to misconceptions; students justify pre/post.

- After reading, students flip one stance and cite a specific line or datum.

Feedback & Assessment

Low-Threat / Formative Assessment

Frequent checks for understanding, without grading pressure, surface misconceptions early.

Evidence:

Bangert-Drowns, Kulik & Kulik (1991) ·

ERIC (2019)

- Use 2–3 ungraded checks (thumb, mini-whiteboard, 1-question poll) per lesson.

- Exit ticket: “One thing I’m unsure about is…”—address at start of next class.

Detailed / Task-Specific Feedback

Tell students where they are relative to criteria and what to do next—not just a score.

Evidence:

Hattie & Timperley (2007) ·

ERIC (2007)

- Comment with one strength tied to criteria + one precise next step.

- Replace grades on first drafts with a 2-line “next move” note; revise in class.

Related: TeachThought: 13 Concrete Examples of Effective Learning Feedback

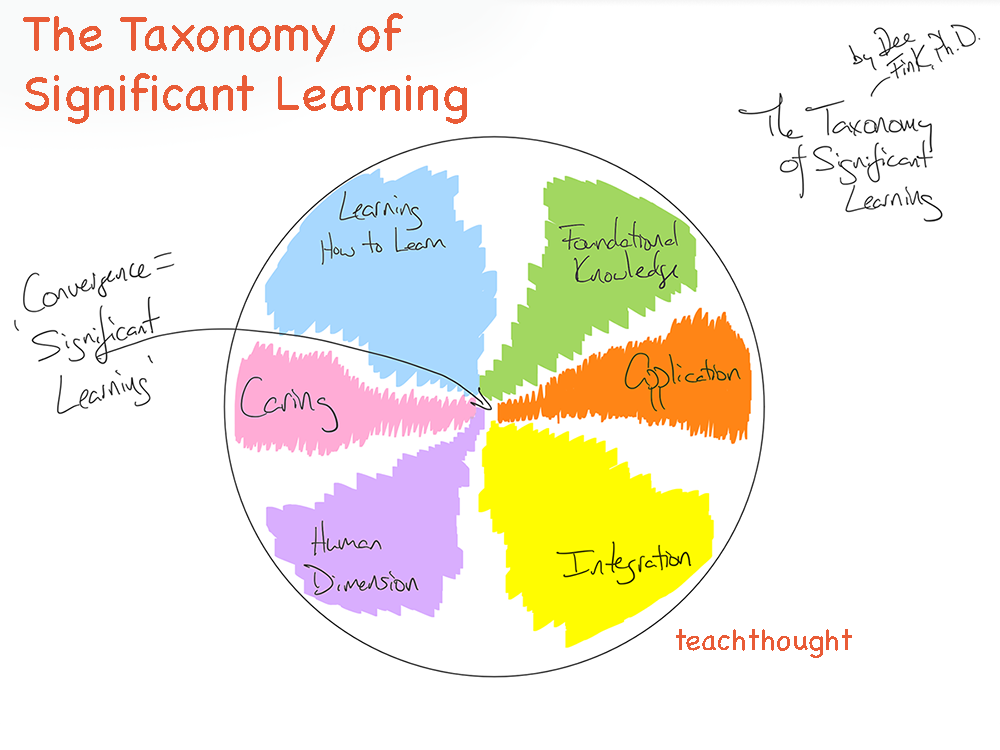

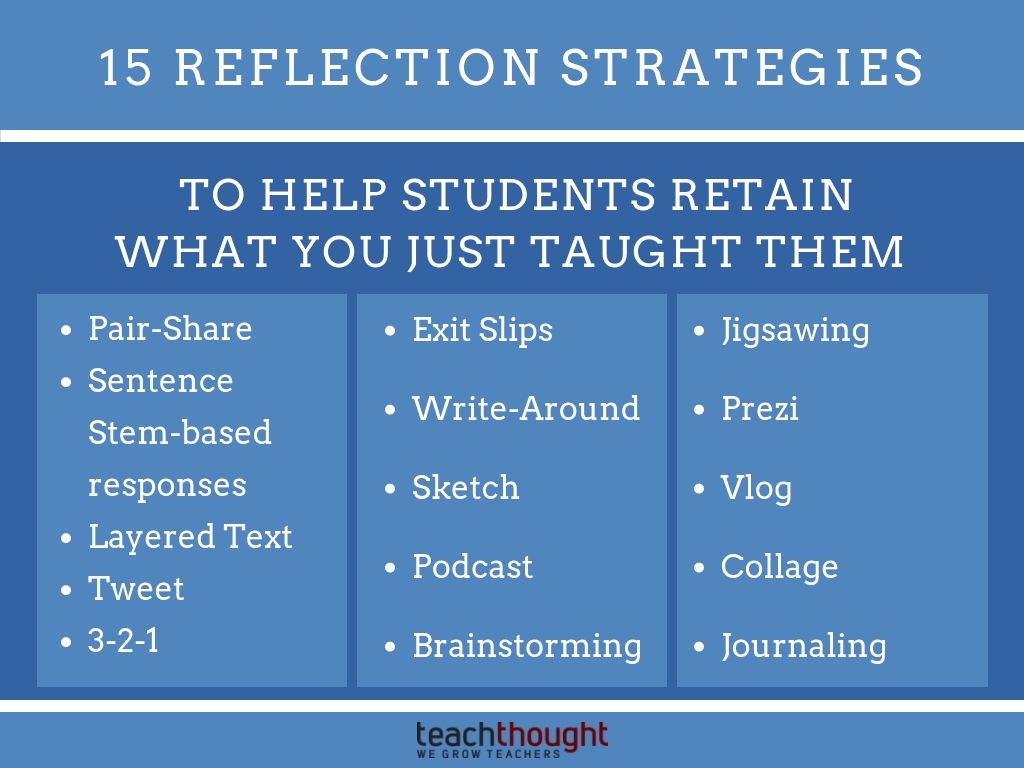

Metacognitive Reflection

Guide students to monitor progress, choose strategies intentionally, and revise based on evidence of learning.

Evidence:

Flavell (1979) ·

ERIC (2019)

- Students name the strategy they used and why in one sentence on the work.

- Three-item self-check: “What worked? What didn’t? What I’ll try next.”

Related: TeachThought: 50 Questions That Promote Metacognition

Higher-Level Questioning

Ask open, cognitively demanding prompts that require students to justify, connect, or transform ideas.

Evidence:

Redfield & Rousseau (1981) ·

ERIC (1989)

- Prep three prompts: explain, connect, transform (“How would this change if…?”).

- After an answer, require a follow-up “Because…” sentence or a classmate challenge.

Related: TeachThought: Question Stems for Higher-Level Discussion

Reinforcing Effort & Recognition

Acknowledge students for meeting explicit performance criteria and for effective strategies—not for generic “trying.”

Evidence:

Deci, Koestner & Ryan (1999) ·

ERIC (2000)

- Tie recognition to a posted criterion (e.g., “Meets: includes counterclaim with evidence”).

- Use intermittent shout-outs for effective strategies (“You compared sources before deciding”).

Homework With a Clear Purpose (Later Grades)

Homework is most effective when reinforcing taught material with a clear learning purpose and minimal parental involvement.

Evidence:

Cooper (1989) ·

ERIC (2012)

- Label homework with a purpose tag (“practicing X,” “preparing for Y”).

- Include a 60-second self-check key so students verify process, not just answers.

Transfer & Student Independence

Inquiry-Based Learning

Students investigate questions or problems through evidence gathering and reasoning.

Evidence:

Hmelo-Silver et al. (2007) ·

ERIC (2014)

- Start with a driving question and a short list of approved sources/tools.

- Checkpoint form: hypothesis → plan → evidence log → next questions.

Related: TeachThought: 20 Questions to Guide Inquiry-Based Learning

Independent Practice

Students apply newly learned skills without scaffolds to build fluency and generalization.

Evidence:

Rosenshine (2012) ·

ERIC (2012)

- Set a fluency goal (correct in a row / within time) and chart progress.

- 3 scaffolded problems → 3 independent problems → 1 reflection line.

Directed Reading–Thinking Activity (DR-TA)

Pause periodically to predict, read, check, and revise; strengthens inference and monitoring.

Evidence:

Stauffer (1969) ·

ERIC (1976)

- Pause every 2–3 paragraphs: predict → read → check → revise.

- Students annotate predictions with ✓ / ✗ and explain any change.

Question–Answer Relationship (QAR)

Teach question types (“Right There,” “Think & Search,” “Author & Me”) so students choose the correct strategy.

Evidence:

Raphael (1982) ·

ERIC (1987)

- Color-code questions: Right There (green), Think & Search (blue), Author & Me (yellow).

- Students must label the QAR type before answering.

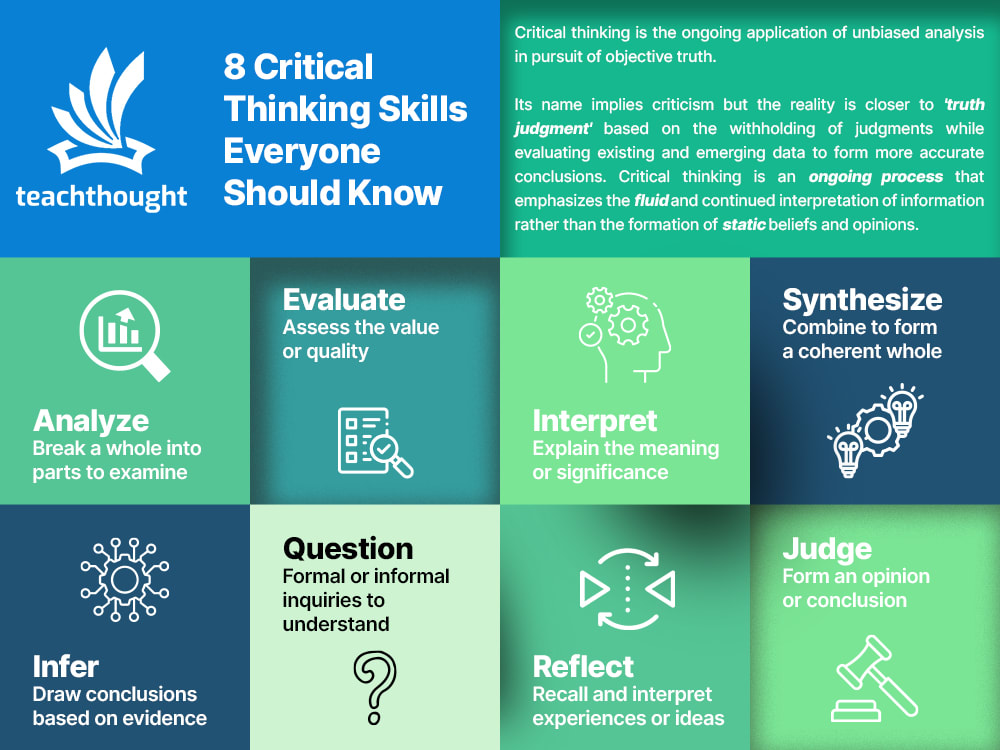

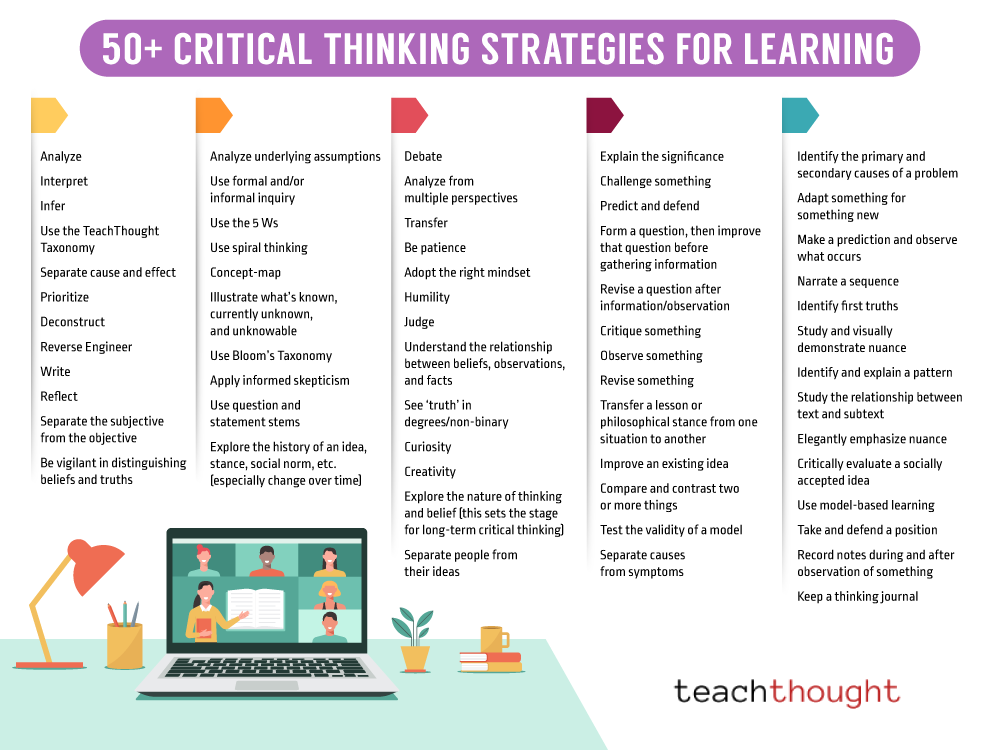

Related: TeachThought: Critical Thinking

KWL & Previewing Structures

Activate background knowledge, articulate curiosity, and set a self-guided purpose before reading.

Evidence:

Ogle (1986) ·

ERIC (1992)

- Spend 2 minutes on K/W; revisit L at exit with an evidence-based sentence.

- Build a class “W wall” and assign each student one W to answer by Friday.

Response Notebooks / Journals

Routinely reflect, question, and reorganize ideas in writing to build transfer via self-explanation.

Evidence:

Readence, Moore & Rickelman (2002) ·

ERIC (2003)

- Standing 3-line prompt: “Today I realized… / I’m stuck on… / Next I will…”

- Require one quote or figure referenced in each entry (with page/line).

Individualized Instruction

Differentiate paths, pacing, or supports so students work at the edge of their competence toward common goals.

Evidence:

Bloom (1984) ·

ERIC (1986)

- Offer 2-path choices: Practice A (more modeling) vs Practice B (extension/transfer).

- Create 3 “just-in-time” mini-lessons students can opt into after a self-check.

Related: TeachThought: Teaching & Pedagogy

32 Research-Based Instructional Strategies For Teachers

1. Setting Objectives

2. Reinforcing Effort/Providing Recognition

3. Cooperative Learning

4. Cues, Questions & Advance Organizers

5. Nonlinguistic Representations (see Teaching With Analogies)

6. Summarizing & Note Taking

7. Identifying Similarities and Differences

8. Generating & Testing Hypotheses

See also Hattie’s Index Of Effect Sizes

9. Instructional Planning Using the Nine Categories of Strategies

10. Rewards based on a specific performance standard (Wiersma 1992)

11. Homework for later grades (Ross 1998) with minimal parental involvement (Balli 1998) with a clear purpose (Foyle 1985)

12. Direct Instruction

13. Scaffolding Instruction

14. Provide opportunities for student practice

15. Individualized Instruction

16. Inquiry-Based Teaching (see 20 Questions To Guide Inquiry-Based Learning)

See also The 40 Best Classroom Management Apps & Tools

17. Concept Mapping

18. Reciprocal Teaching

19. Promoting student metacognition (see 5o Questions That Promote Metacognition In Students)

20. Developing high expectations for each student

21. Providing clear and effective learning feedback (see 13 Concrete Examples Of Effective Learning Feedback)

22. Teacher clarity (learning goals, expectations, content delivery, assessment results, etc.)

23. Setting goals or objectives (Lipset & Wilson 1993)

24. Consistent, ‘low-threat’ assessment (Bangert-Drowns, Kulik, & Kulik 1991; Fuchs & Fuchs 1986)

25. Higher-level questioning (Redfield & Rousseau 1981) (see Questions Stems For Higher Level Discussion)

26. Learning feedback that is detailed and specific (Hattie & Temperly 2007)

27. The Directed Reading-Thinking Activity (Stauffer 1969)

28. Question-Answer Relationship (QAR) (Raphael 1982)

29. KWL Chart (Ogle 1986)

30. Comparison Matrix (Marzano 2001)

31. Anticipation Guides (Buehl 2001)

32. Response Notebooks (Readence, Moore, Rickelman, 2002)

Sources: Marzano Research; Visible Learning; http://www.sde.ct.gov/sde/lib/sde/pdf/curriculum/section7.pdf ; 32 Research-Based Instructional Strategies

TeachThought Staff

Source link