[ad_1]

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

Political partisans are always dreaming of final victories. Each election raises the hope of realignment—a convergence of issues and demographics and personalities that will deliver a lock on power to one side or the other. In my lifetime, at least five “permanent” majorities have come and gone. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s landslide triumph over Barry Goldwater in 1964 seemed to ratify the postwar liberal consensus and doom the Republican Party to irrelevance—until, four years later, Richard Nixon’s narrow win augured an “emerging Republican majority” (the title of a book by his adviser Kevin Phillips) based in the white, suburban Sun Belt. In 1976, Jimmy Carter heralded a winning interracial politics called “the Carter coalition,” which proved even shorter-lived than his presidency. With Ronald Reagan, the conservative ascendancy really did seem perpetual. After the Republican victory in the 2002 midterm elections, George W. Bush’s operative Karl Rove floated the idea of a majority lasting a generation or two.

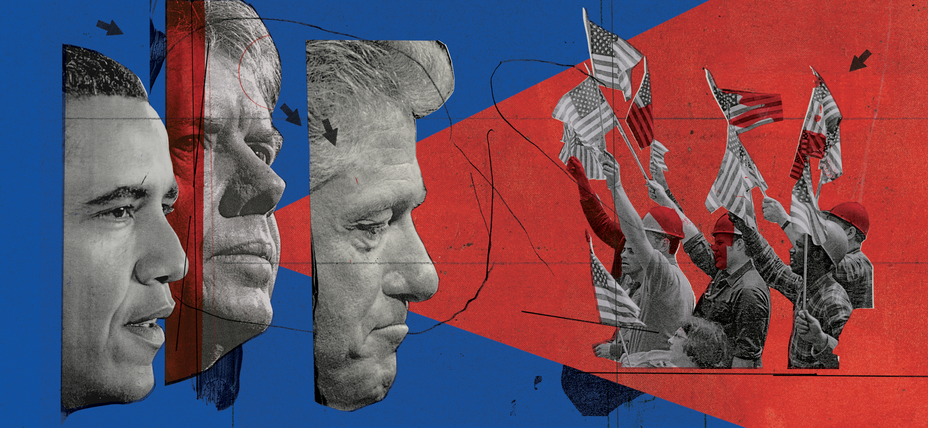

But around the same time, the writers John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira published The Emerging Democratic Majority, which predicted a decades-long advantage for the party of educated professionals, single women, younger voters, and the coming minority majority. The embodiment of their thesis soon appeared in Barack Obama—only to be followed by Donald Trump and the revenge of the white working class, a large plurality that has refused to fade away.

Recent American history has been hard on would-be realigners. The two parties are playing one of the longest deuce games since the founding. Even with the structural distortion of the Senate and the Electoral College favoring Republicans, the American people remain closely divided. The Democratic presidential candidate has won seven of the last eight popular votes, while the national vote for the House of Representatives keeps swinging back and forth between the parties. Stymied by a sense of stalemate, both now indulge in a form of magical thinking.

Neither side believes in the legitimacy of the other; each assumes that the voters agree and will soon sweep it into power. So the result of every election comes as a shock to the loser, who settles on explanations that have nothing to do with the popular will: foreign interference, fraudulent ballots, viral disinformation, a widespread conspiracy to cheat. The Republican Party tries to hold on to power by antidemocratic means: the Electoral College, the filibuster, grotesquely gerrymandered legislatures, even violence. The Democratic Party pursues a majority by demography, targeting an array of identity groups and assuming that their positions on issues will be predictably monolithic. The latter is a mistake; the former is a threat to democracy. Both are ways to escape the long, hard grind of organized persuasion that is politics.

Two other jarring features define our age of deadlock. One is a radical shift in the two parties’ center of gravity. The signature of elections today is the class divide called education polarization: In 2020, Joe Biden won by claiming a majority of college-educated white voters, the backbone of the old Republican Party. Trump, with a lock on the white working class, lost despite making gains among nonwhite, non-college-educated voters, yesterday’s most reliable Democrats. Meanwhile, on the political stage, cultural and social issues have eclipsed economic issues—even as every facet of American life, whether income or mortality rates, grows less equal and more divided by class.

These two trends are obviously related, and they have a history. From the late 1970s until very recently, the brains and dollars behind both parties supported versions of neoliberal economics: one hard-edged and friendly to old-line corporate interests such as the oil industry, the other gentler and oriented toward the financial and technology sectors. This consensus left the battleground open to cultural warfare. The educated professionals who dominate the country’s progressive party have long cared less about unions, wages, and monopoly power than about race, gender, and the environment. In the summer of 2020, millions of young people did not come out of isolation to protest the plight of meatpackers laboring in COVID-ridden processing plants. They were outraged by a police killing, and they called for a “racial reckoning”—a revolution in consciousness that ended up having little effect on the lives of the poor and oppressed.

For their part, Republicans have spoken the traditionalist language of the working class ever since Nixon’s “silent majority”; Trump dropped the mantra of low taxes and deregulation that used to excite the party when it was more upscale, and directed his message to a base that votes on issues such as crime, immigration, and what it means to be an American. More recently, Republican candidates have turned to anti-“woke” rhetoric. In losing its voice as the champion of workers, the Democratic Party lost many of the workers themselves, and during the past half century, the two parties have nearly switched electorates.

This remapping helps explain the outpouring of new books that pay political attention to those overlooked Americans of all races who lack a college degree, many employed in jobs that pay by the hour—factory workers, home health aides, delivery drivers, preschool teachers, hairdressers, restaurant servers, farm laborers, cashiers. During the pandemic, they were called “essential workers.” Now they’ve been discovered to hold the key to power, giving rise to yet another round of partisan dreaming of realignment, this time hinging on the working class. But these Americans won’t benefit from their new status as essential voters until the parties spend less effort coming up with what they think the working class wants to hear, and more effort actually delivering what it wants and needs.

The economic decline and political migration of the American working class receive the most compelling treatment in Ours Was the Shining Future: The Story of the American Dream, by the New York Times writer David Leonhardt. He describes the rise and fall, from the New Deal to the present, of what he calls “democratic capitalism”—not a neutral phrase, but a positive term for a mixed economy that benefits the many, not just the few. By now, the story of growing inequality and declining mobility is familiar from the work of Thomas Piketty, Gary Gerstle, Raj Chetty, and other scholars. Leonhardt has a gift for synthesizing complex trends and data in straightforward language and persuasive arguments whose rationality doesn’t fully mute an undertone of indignation. He appreciates the power of stories and weaves obscure but telling events and people into his larger narrative: a 1934 strike in the Minneapolis coal yards that showed the political potential of worker solidarity; the mid-century businessman Paul Hoffman, who argued to members of his own class that they would benefit from a prosperous working class; the pioneering computer programmer and Navy officer Grace Hopper, who saw the economic benefits of military spending on technological research.

An economy that gives most people the chance for a decent life doesn’t arise by accident or through impersonal forces. It has to be created, and Leonhardt identifies three agents: political action, such as union organizing, that gives power to the have-nots; a civic ethos that restrains the greed of the haves; and public spending on people, infrastructure, and ideas—“a form of short-term sacrifice, an optimistic bet on what the future can bring.”

All three—power, culture, and investment—combined in the postwar decades to transform the American working class into the largest and richest middle class in history. Black Americans, even while enduring official discrimination and racist violence, closed the gap in pay and life expectancy with white Americans—progress, Leonhardt writes, that “reflected class-based changes more than explicitly race-based changes.” In other words, the right of workers to form unions, an increased and expanded federal minimum wage, and a steeply progressive tax code that funded good schools all reduced racial inequality by reducing economic inequality. But after the 1960s, the economy’s growth slowed, and the balance of power among the classes grew lopsided. American life became stratified. Wealth flowed upward to the few, unions withered, and public goods such as schools starved. In their rush to cash in, elites knocked over taboos that had once restrained the worst extremes of greed. Metropoles prospered and industrial regions decayed. Despite the end of Jim Crow and the growth of a Black professional class, the gap between Black and white Americans began to widen again as the country’s top 10 percent pulled away from the rest.

This economic analysis comes with a political argument that will not be welcomed by many progressives. Leonhardt places blame for the decline of the American dream where it belongs: on free-market intellectuals, right-wing politicians, corporate money. But he also points to the shortsighted complacency of union leaders, and, even more, the changing values and interests of well-educated, comfortable Democrats. Beginning in the early ’70s, they dropped concern about bread-and-butter issues for more compelling causes: the environment, peace, consumer protection, abortion, identity-group rights. The labor movement lost interest in social justice, and progressive politicians lost interest in the working class. Neither George Meany nor George McGovern sang from the New Deal songbook. After the ’60s, “the country no longer had a mass movement centered on lifting most Americans’ living standards.”

Why did the white working class abandon the party that had been its champion? “In the standard progressive telling,” Leonhardt writes, “the explanation for this political shift is race.” Race had a lot to do with it, and Leonhardt affirms that Democrats’ embrace of the Black freedom movement in the ’60s, followed by white backlash (exploited by Republicans with their “southern strategy”) and persistent racism, is a major cause. But the progressive telling falls short on three counts. It’s morally self-flattering and self-exonerating; it’s politically self-defeating (accusing voters of racism, even if deserved, is not the way to convince them of anything); and it fails to explain too many recent political trends. For example, nearly all-white West Virginia remained mostly Democratic decades after the passage of the Civil Rights Act and only turned indelibly red in 2000. According to one estimate, almost a quarter of the working-class white voters who gave Trump the presidency in 2016 had voted for a Black president only a few years earlier. The stark polarization of the current college-educated and non-college-educated white electorate shows the key role of class. And what are we to make of an openly bigoted president running for a second term and increasing his share of the Black and Latino vote?

Leonhardt’s subtler account is rooted in the working class’s growing cultural and economic alienation from a Democratic Party ever more dominated by elites and activists, and out of touch on the issues that hurt less affluent Americans most, especially crime, trade, and immigration. The financial crisis of 2008 was a pivotal event, leaving large numbers of Americans with the sense that the country’s upper classes were playing a dirty game at the expense of the rest.

That fall, I reported on the presidential campaign in a dying coal town in Appalachian Ohio. To my surprise, its white residents were giving Obama a close hearing, and he ended up doing better in the region than John Kerry had. But at a local party gathering, an older white man told me that neither party had done anything to reverse the decline of his town, and that he would no longer vote Democratic, for one reason: illegal immigration. I listened politely and discounted his grievance—I didn’t see any undocumented immigrants in Glouster, Ohio. Why did he care so much?

Leonhardt provides an answer. In a comprehensive analysis, he shows that the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which liberal politicians sold as nondiscriminatory but still restrictive, opened the gates to mass immigration. The result put downward pressure on wages at the lower end of the economy. Again, racial resentment partly explains hostility to large-scale immigration, but Leonhardt shows that rapid demographic change can erode the social bonds that make collective efforts for greater equality possible: “Low immigration numbers in the mid-1900s improved the lives of recent immigrants by fostering a stronger safety net for everybody.” As Democrats were reminded in 2022’s midterms, immigration is less popular among working-class Americans of all races than among college graduates. The mayor of my very progressive city, a son of the Black working class, recently sounded like that working-class white ex-Democrat in Ohio when he warned that the arrival of more than 100,000 migrants “will destroy New York.”

These positions reflect class differences in approaches to morality. Drawing on social-science research, Leonhardt distinguishes between “universal” values such as fairness and compassion, which matter more among educated professionals, and “communal” values such as order, tradition, and loyalty, which count more lower down the class ladder. It shouldn’t be surprising that working-class Americans of color sympathize with migrants but don’t necessarily want an open border, that they fear crime at least as much as police misconduct. But their views confound progressives, who see these issues through the almost metaphysical lens of group identity—the belief that we think inside lines of race, gender, and sexuality, that these accidental and immutable traits dictate our politics.

This worldview provided a sense of meaning to a generation that came of age after 2008, amid upheaval and disillusionment. Because the new progressivism flourished among younger, educated Americans who lived online, its cultural reach was disproportionate, making rapid inroads in universities, schools, media, the arts, philanthropy. But its believers badly overplayed their hand, giving Republicans easy wins and driving away ordinary Democrats. Americans remain a wildly diverse, individualistic, aspirational people, with rising rates of mixed marriage, residential integration, and immigration from all over the world. Any rigid politics of identity—whether the left’s obsession with “marginalized communities,” or its sinister opposite in the reactionary paranoia of “white replacement theory”—is bound to shatter against the realities of American life.

Identity politics has been a feverish interlude following the demise of the neoliberal consensus that prevailed from Reagan to Obama. What will take its place? Leonhardt hopes for a Democratic Party that learns how not to alienate the nearly two-thirds of Americans without a college degree. He believes that education can be a force for upward mobility, but that the current version of meritocracy—built-in advantage at the top, underfunding below—has created a highly educated aristocracy. He advises a renewed emphasis on economic populism, a hard line on equal rights for all but reasonable compromise on other controversial social issues, and a general attitude of respect. His hero is the martyred Robert F. Kennedy, whose 1968 presidential campaign was the last to unite working-class Americans of all colors.

A version of the same argument, with less historical depth and feeling but more charts and polemics, can be found in John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira’s Where Have All the Democrats Gone? The Soul of the Party in the Age of Extremes. Judis and Teixeira have been explaining their earlier book’s thesis for two decades even as the majority of its title kept failing to emerge. Now they diagnose their error: “What began happening in the last decade is a defection, pure and simple, of working-class voters. That’s something that we really didn’t anticipate.” Like Leonhardt, they call on Democrats to embrace New Deal–style “economic liberalism” (but not Green New Deal–style socialism) and to reject “today’s post-sixties version of social liberalism, which is tantamount to cultural radicalism.” In a series of scathing chapters, Judis and Teixeira show how far left the Democrats’ “shadow party” of activists, donors, and journalists has moved in the past 20 years on immigration, race, gender, and climate.

The authors want a return to the party’s cultural centrism of the ’90s. Instead of decriminalizing the border, which most 2020 Democratic presidential candidates advocated, they call for tighter border security, enforcement of laws that prohibit hiring undocumented immigrants, and a way for those already here to become citizens. They show that middle-ground policies like these and others—the pursuit of racial equality that focuses on expanding opportunity for individuals, not equity of group outcomes; support for equal rights for trans Americans without insisting on a gender ideology that denies biological sex—remain majority views, including among nonwhite Americans. Judis and Teixeira are less persuasive on climate change: Although their gradualism might be politically helpful to Democrats, the country and the planet will be at the mercy of extreme weather that’s indifferent to such messaging.

Joshua Green’s fast-paced, sober, yet hopeful The Rebels: Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and the Struggle for a New American Politics argues that a Democratic renewal is already under way. Like Leonhardt, Judis, and Teixeira, Green traces the Democrats’ estrangement from working Americans back to the ’70s; he begins his story with a moment in 1978, when Jimmy Carter abandoned unions for Wall Street. The narrative reaches a climax in 2008, when the financial crisis destroyed home values and retirement savings while taxpayer dollars rescued the banks that had triggered it, convincing large numbers of Americans that the system was rigged by financiers and politicians. Because of policy choices by the Obama administration—Democrats’ last spasm of neoliberalism—much of the blame fell on the former party of the common people.

Yet out of the wreckage rose a new group of Democratic stars who sounded like their New Deal predecessors, many of whom were every bit as radical. Taking aim at corporate elites, Green’s protagonists want to increase economic equality through worker power and state intervention. Though Sanders and Warren failed as presidential candidates, Green argues that their populism transformed the party, including the formerly moderate Joe Biden, who has pushed a remarkably ambitious legislative agenda with working-class interests at its center.

Green is a first-rate journalist, but his book suffers from a blind spot: It ignores the role of culture in the party’s struggles with the working class. His analysis omits half the story until the 2016 election, when, he acknowledges, Trump “reshuffled Democratic priorities. As he moved cultural issues to the center of national political conflict, race, gender, and immigration eclipsed populist economics as the focus of the liberal insurgency.” In the face of Trump’s bigotry, Democrats felt compelled to adopt the “maximalist” positions of activists, assuming that these would align the party with “the groups on the receiving end of Trump’s ugliest barbs,” such as Latino immigrants. Instead, the party’s working-class losses began to extend beyond white voters. Green’s answer is to double down on economic populism: “Rather than fear the Republicans’ culture wars—or respond to them by racializing policies that benefit everyone—Democrats should take the opportunity to reestablish the party as serving the interests of working people of every race and ethnicity.”

None of these books offers a shortcut to a new Democratic majority. The erosion of working-class support is too old and too severe to be easily reversed. In fact, it’s the Republican pollster Patrick Ruffini, in Party of the People: Inside the Multiracial Populist Coalition Remaking the GOP, who imagines a coming realignment—for Republicans. Ruffini can’t resist making the case that, in addition to transforming the party, this coalition could become the next permanent majority. To do so, he breezes through some of the same history, and reaches a similar conclusion: Democrats have fallen into a “cosmopolitan trap,” losing their hold on a key constituency in the process.

Ruffini’s most original contribution is to apply close statistical analysis to the past few election cycles as he builds his case for a Republican multiracial coalition. He supplies strong evidence of the moderate social views of most Black, Latino, and Asian American voters. On that basis, Ruffini doesn’t think Democrats can win back their lost supporters just by changing the subject to class. “Democrats may calculate that, simply by focusing on economic issues, they can keep cultural issues from eating into their base,” but they’re wrong, he writes. “When voters’ economic views and social views are in conflict, one’s social stances more often drive voting behavior … Cultural divides are what voters vote on even if politicians don’t talk about them.” Ruffini offers no data to support this conclusion, but it underpins his counsel for a politician like Biden. Never mind his legislative accomplishments that benefit the working class; what he really needs, Ruffini advises in political-operative mode, is a “hard pivot against the cultural left”—he seems to have in mind a Sister Souljah moment—to neutralize Republican attacks.

Though Ruffini doesn’t spend much time on economic policy, it’s worth noting that a few high-profile Republicans have recently discovered that monopolistic corporations can be oppressors, that capitalism tears communities apart. Senators Josh Hawley of Missouri and Marco Rubio of Florida, as well as other politicians, limit this insight to their partisan enemies in Silicon Valley, but a few conservative writers, such as Sohrab Ahmari, the author of Tyranny, Inc.: How Private Power Crushed American Liberty—And What to Do About It, are open to ideas of social democracy. This internal party battle between the old libertarians and the new egalitarians doesn’t seem to interest Ruffini; oddly, given his populist ambitions, he remains unmoved by the anti-corporate critique. Nor does he have much to say about the Republican Party’s descent with Trump into authoritarian nihilism.

Ruffini’s formative years as a professional Republican came during the George W. Bush presidency, and his thinking hasn’t kept up with the America of fentanyl and Matt Gaetz. The populist future of Ruffini’s desires is a wholesome mixture of culturally conservative, “pro-capitalist” families and low taxes. His “commonsense majority” would combine white people who didn’t graduate from college and nonwhite people of all classes, because “the education divide makes a much bigger difference in the attitudes of whites than it does among nonwhites.” It sounds like a twist on the Judis-Teixeira emerging majority of two decades ago. Demography as destiny seduces realigners on both sides.

Ruffini recognizes that Republicans are a long way from attracting enough nonwhite voters to achieve his majority. But, he argues, if the party battles job discrimination based on a college degree, makes voting Republican socially acceptable among Black Americans, and apologizes for the southern strategy, his goal could be realized by 2036. By then, the Democratic Party would presumably be a pious rump of overeducated white people demanding open borders and anti-racist math.

These writers are all trying to solve a puzzle: One party supports unions, the child tax credit, and some form of universal health care, while the other party does everything in its power to defeat them. One president passed major legislation to renew manufacturing and rebuild infrastructure, while his predecessor cut taxes on the rich and corporations. Yet polls since 2016 have shown Republicans closing the gap with Democrats on which party is perceived to care more about poor Americans, middle-class Americans, and “people like me.” During these years, the energy on the left has been fueled by an identity politics that resisted Trump and became the orthodoxy of educated progressives, with its own daunting lexicon. Many Democrats fell silent, out of fear or shame or confusion.

Now, encouraged perhaps by the excesses and failures of a professional-class social-justice movement, and by the relative success of Biden’s pro-worker agenda, they seem to be finding their voice. Judis and Teixeira cite polling data from Wisconsin and Massachusetts as evidence that Americans are less divided on cultural issues than activists on both sides, who benefit by stoking division, would like: “If you look at the country’s voters, and put aside the culture wars, what you find are genuine differences between the parties’ voters over economic issues.” The real disagreements have to do with taxation, regulation, health care, and the larger problem of inequality. Democrats’ way forward seems obvious: emphasize differences on economics by turning left; mute differences on culture by tacking to the middle. If the party can free itself from the moneyed interests of Wall Street and Silicon Valley, and the cultural radicalism of campus and social media, it might start to win in red states.

I want Leonhardt, Judis, Teixeira, and Green to be right. Having long held the same views, I’m an ideal audience for these books and other new ones making related arguments, such as Yascha Mounk’s The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time, Susan Neiman’s Left Is Not Woke, and Fredrik deBoer’s How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement. Yet the solutions that some of them propose for the Democrats’ working-class problem leave me with a worrying skepticism. In an age of shredded social bonds and deep distrust of institutions, especially the federal government, we can’t go back to New Deal economics. If Ruffini is right, the culture wars aren’t easily put aside. “Guns and religion,” in Obama’s unfortunate phrase, are genuinely held values, not just proxies for economic grievance; conservative politicians manipulate them, but they aren’t inauthentic. Race and gender are more important categories than class for millions of Americans, especially younger ones. Illegal immigration legitimately vexes citizens living precarious lives. Social issues aren’t manufactured by power-hungry politicians to divide the masses. They matter—that’s why they’re so polarizing.

The working class is immense, varied, and not all that amenable to being led. It’s more atomized, more independent-minded, more conspiracy-minded and cynical than it was a couple of generations ago. Although unions are gaining popularity and energy, only a tenth of workers belong to one. Abandoned to an unfair economy while the rich freely break the rules, bombarded with images of fame and wealth, awash in drugs, working-class Americans are less likely to identify with underdogs like Rocky and Norma Rae or the defeated heroes of Springsteen songs than to admire celebrities who pursue power for its own sake—none more so than Trump.

The argument over which matters more, economics or culture, may obsess the political class, but Americans living paycheck to paycheck, ill-served by decades of financial neglect and polarizing culture wars, can’t easily separate the two. All of it—wages, migrants, police, guns, classrooms, trade, the price of gas, the meaning of the flag—can be a source of chaos or of dignity. The real question is this: Can our politics, in its current state, deliver hard-pressed Americans greater stability and independence, or will it only inflict more disruption and pain? The working class isn’t a puzzle whose solution comes with a prize—it isn’t a means to the end of realignment and long-term power. It is a constituency comprising half the country, whose thriving is necessary for the good of the whole.

This article appears in the January/February 2024 print edition with the headline “What Does the Working Class Really Want?”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

[ad_2]

George Packer

Source link