[ad_1]

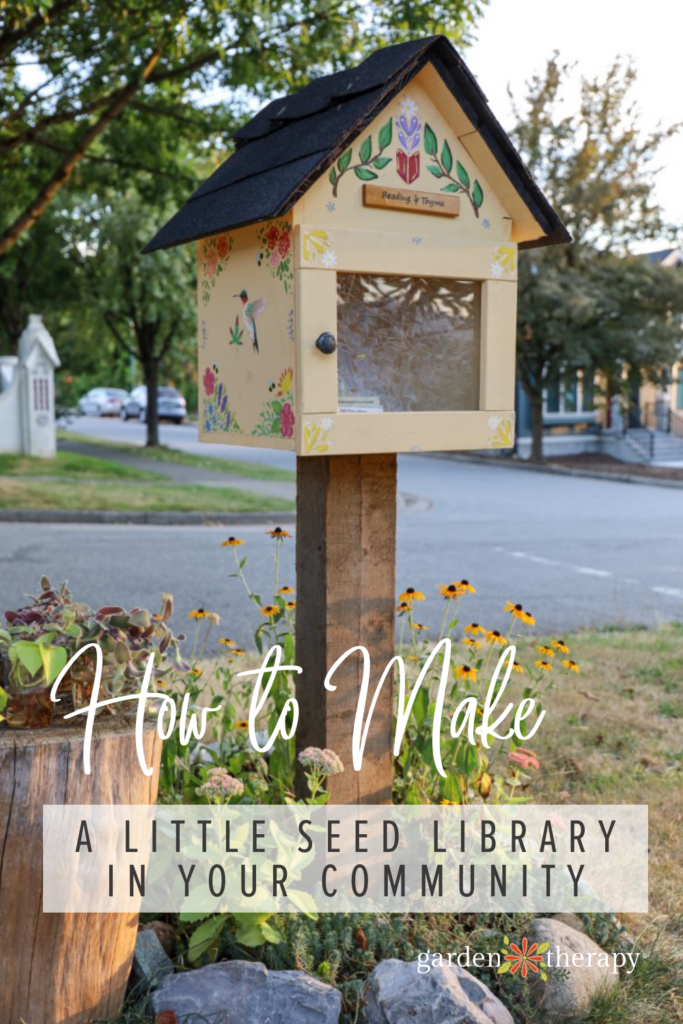

The love of gardening begins with a seed. Through a seed library, you can encourage others in your neighbourhood to find this love and spread some seedling joy. Rising in popularity, seed libraries have become community hubs to share seeds and extras supplies so everyone can have blooming, thriving gardens. Here’s how to find one in your neighbourhood or start one of your very own!

I’m obsessed with my neighbourhood. It’s been the perfect place to raise my kiddo, between his after-school centre to the lake down the road for daily walks. I know my neighbours well, making wreaths with them during the holidays and talking plants in the summer.

The reason it’s so great is the sense of community here. No one hesitates to buy from the local kid’s lemonade stand or lend out a garden tool if someone needs to borrow it. While I love the community gardens, bulletins, and parks, one of the things I adore the most are seed libraries. They are the combination of two of my favourite things…community and the garden!

Seed libraries are one of the many projects in my upcoming book, The Regenerative Garden. Inside the book, I include many sustainable practices and concepts to employ in the garden as well as over 80 projects and designs to help you implement the ideas.

I dedicated a whole chapter to building community, including seed libraries! Be sure to check it out to see many, many more interesting projects to implement in your garden.

This post will cover…

What is a Seed Library?

Much like Little Free Libraries, seed libraries are tiny places throughout the community where people can find free items. Inside, local members of the community share seeds either purchased in excess or gathered from seeds in their own garden. You can also find easily accessible seedlings, plants, cuttings, and seed-starting supplies all for free.

Seed libraries have a host of benefits. They’re an opportunity to share skills and knowledge with neighbours, bring greater food security, and provide environmental benefits.

I love seeing seeds that come from someone’s own garden best, as you know they come from a plant that has already grown in your microclimate. It’s a sure sign of success for your own garden!

A local seed library can also share heirloom seeds that may be difficult to come by otherwise. These are such special seeds, and sharing them with the community is a treat.

In my neighbourhood, the Zucchini Racer committee donates zucchini seeds to all the community libraries so that community members can grow their own racer for the Fall Fair. It’s something Kiddo and I love to partake in together.

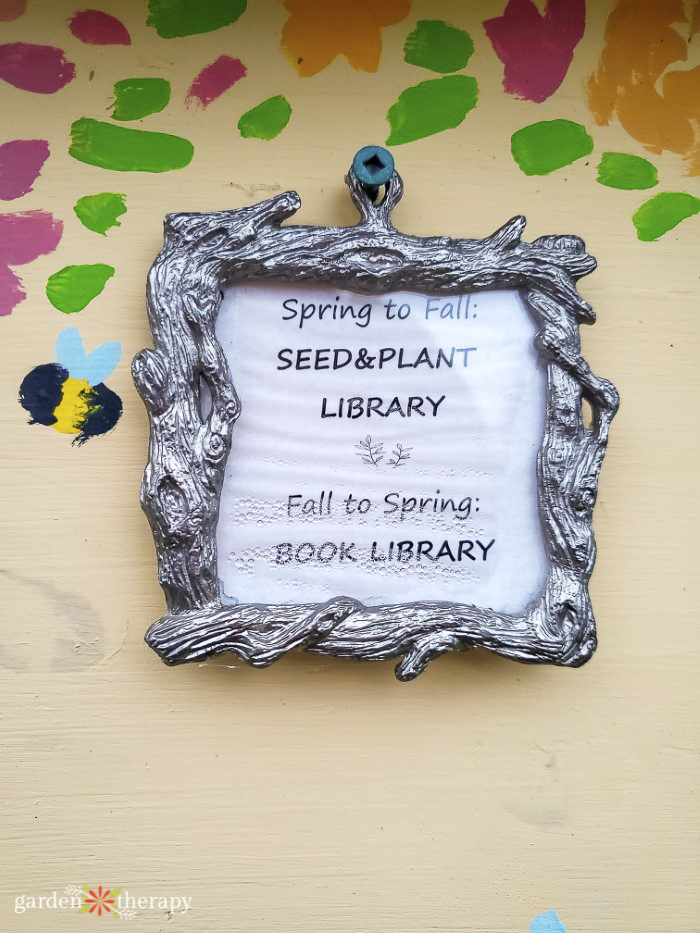

In some areas, the seed library switches to a little free book library in winter that focuses on gardening and nature. This makes them a useful pitstop and gardening hub year-round.

How to Find a Seed Library Near Me

The boxes are not large and you can find them in the most surprising of places. Most are run by a member of the community in front of their front yard. Others can be found inside community gardens, by community centres, or churches.

A great place to start is actually by searching for a Little Free Library. These tend to be easier to find and are even listed on Google Maps sometimes. Some have accompanying seed libraries or may have seeds and other free items in addition to books.

Some libraries even have seed lending programs. A local horticultural group or Facebook group may also be a good resource when seeking out a seed library near you.

Your best bet? Take a walk through the neighbourhood. Once you are looking for something, you begin to see it everywhere! And if you can’t find one, maybe it’s time to start one yourself.

How to Make Your Own Seed Library

Besides making the actual seed library, there are a few main components you may not have considered, including managing the space and getting community members to engage.

Build

I have seen seed libraries made of all kinds of materials. They can look similar to a Little Free Library, where they become an art project in itself, or can be as simple as a plastic container on a post. Most are made from recycled or found materials like cabinets or old public newspaper boxes.

Since the structure will be outside, you need to make sure it stays nice and dry inside and can withstand the elements. A weatherproof, sloped roof will ensure that water runs off rather than in. Outdoor paint protects the walls as well. You also want to make sure the door to where the seeds are kept is able to shut securely.

Make sure the library is in an easily accessible public space. You should also check with local bylaws that you’re allowed to build such a structure.

Then, list the location online so that people can search for and find it.

Stock

Once the structure is ready, it’s time to fill it full of seeds. When first starting, you can reach out to local seed companies for stock that they will need to redistribute to the community before it expires.

Besides seeds, include information on how to plant seeds, tend plants, and save seeds. Stock the shelves with empty seed or coin envelopes and pens. Seed envelopes can also be used to divide seed packages into smaller portions, so everyone takes only what they need.

Manage

A person or a group needs to manage the seed library. Checking on it frequently ensures that there is no weather damage to the structure, the seeds haven’t expired, and whether there needs to be a call out for more materials.

For the most part, these things tend to run fine all on their own from the community members. People are happy to donate their extra seeds and supplies so that fellow gardeners can enjoy what they no longer need.

Encouraging the community to keep the seeds flowing by giving and receiving will refresh the supply enough to circulate plenty of seeds. For all donated seeds, make sure to have a sign encouraging the rules for labelling and providing growing info.

Educate

Seed libraries are great places for beginner gardeners to start exploring their green thumb. Make sure there are also educational resources in the seed library to encourage successful seed starting.

It’s also a good idea to manage expectations for the seed library. Germination rates will not be as good as they would be if the seed packages had been recently collected and stored in a cool, dry location.

The seed-sharing library will not be an ideal climate for long-term storage; many seeds will come from seed companies that are donating old stock, and community members may donate seeds past their prime.

Frequently Asked Questions About Making a Seed Library

Seed libraries help to foster community relationships and encourage the love of gardening. They also exist to share heirloom seeds that work well in certain microclimates and protect food security for many people by growing their own food.

Having one in the community is a great place to connect beginner gardeners with experienced gardeners and to get the conversation around gardening going.

There are many rules and laws guarding the exchange of seeds. Seed libraries enter into a bit of a legal grey area. Most commercial seeds are patented hybridized or GMO seeds. Under the law, farmers cannot save and replant seeds and must buy ones every year.

However, with seed libraries, seeds are not being sold; instead, they are given free to help foster community and the love of gardening. While not completely exempt from seed laws, seed libraries embrace a giving spirit and are usually not a problem in most states and provinces. Be sure to check local bylaws for rules regarding structures such as farm stands.

With all this in mind, I know you’ll create an amazing seed-sharing library for your community to enjoy. If you do set one up, drop it in the comments down below. Someone from your town or city may very well see it!

More Community Building Projects

A city girl who learned to garden and it changed everything. Author, artist, Master Gardener. Better living through plants.

[ad_2]

Stephanie Rose

Source link