When you think of suffering, you might think of war, genocide, or famine. Suffering that is forced upon someone, with no escape, no control over the situation, is absolutely deplorable, absolutely incomprehensible, and also absolutely not the focus of this article.

The suffering I’m concerned with is elective. The kind you sign up for. College admissions committees love this kind: “What obstacles have you overcome?” “What challenges have shaped you?” If you wrote about real agony, they would gasp and clutch their pearls. We must not overshare, lest the rawness make the reader uncomfortable. Save it for your therapist. But elective agony, they eat that shit up. Write about how an ACL tear in your varsity soccer game led you to an interest in sports medicine: instant Ivy League material. Write about how sexual assault led you to clinical depression: instant waitlist. We trot out our micro-traumas as evidence of character. Hardship, we are told, builds mental fortitude. It builds character and molds us into unstoppable forces. And, since there is so much merit in adversity, we often enter into it willingly.

Today, I am on day two of a six-day backpacking trip through the remote wilderness of the Rocky Mountains with my partner, writing this down on a scrap piece of paper with a pencil. Yesterday, we climbed two mountains (~5000 vertical feet), crossing over 19 miles of terrain, carrying our home (tent), kitchen (stove and pots), and all the necessities to survive on our own, packed away on our backs, raking in a combined ~50 pounds. Today, my right foot is swollen. My legs are throbbing. My back is bruised. My odor is offensive – bad enough to extinguish the Cuyahoga if it ever caught fire again. Yet, as I sit here, I feel joy. I’m sure part of that joy is the knowledge that this will end – a warm shower and a cold beer await me on Friday. But it feels like more than that.

There is a peculiar human drive not only to accomplish but to suffer. The Badwater Ultramarathon, for example, is 135 miles through Death Valley in July, where the air itself is hot enough to sauté you. If it were about mileage alone, runners could just loop around beautiful Lake Erie in November until their knees liquefied, then go grab a few rosemary bagels from Cleveland Bagel Company and a coconut water iced latte from Phoenix. But no; the point is the punishment. The point is to cook while climbing. 135 miles around Cleveland is too luxurious. You can’t achieve enlightenment with schmear on your face and the world’s best iced latte. With the Badwater Ultramarathon, suffering is not the obstacle. Suffering is the substance.

We see this across history. Mother Teresa and Saint Francis of Assisi denounced comfortable lives to embrace poverty as if it were haute couture. Buddhist monks fast and seclude themselves into enlightenment. Jean-Jacques Savin crossed the Atlantic stuffed inside a barrel, while Joey Chestnut punishes himself by stuffing barrels of meat into his body – 70 hot dogs in 10 minutes, a feat equal parts impressive and alarming. Even Forrest Gump, cinema’s great philosopher, ran across America “for no particular reason.” The reason, of course, is to suffer.

Which brings us to Cleveland.

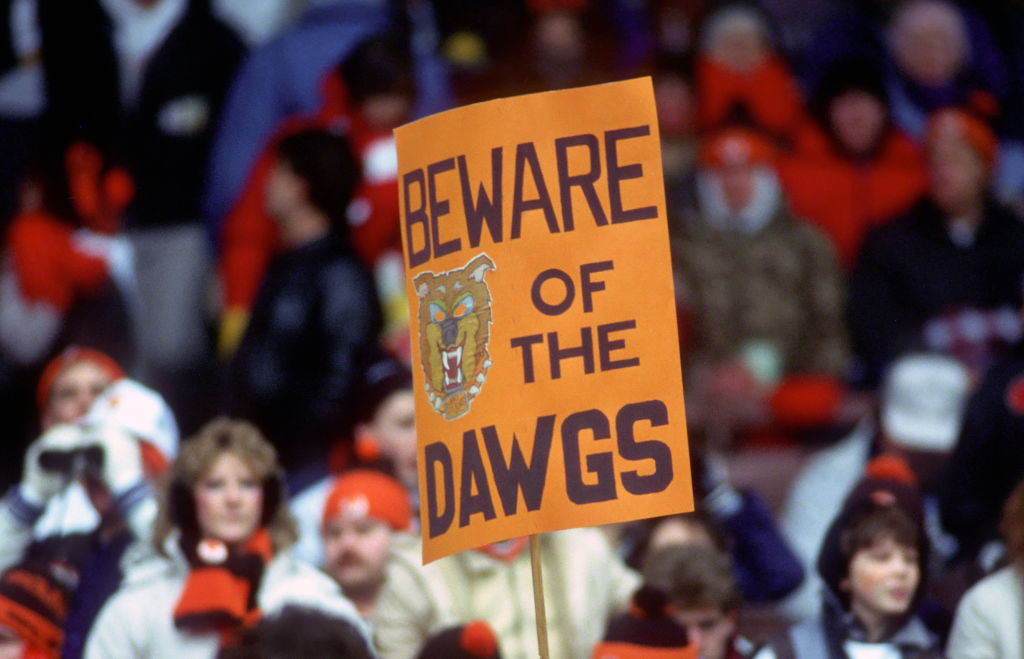

It turns out this drive to endure is not limited to wilderness of ultramarathons. In my own backyard, 17 times a year, I witness another kind of suffering. Being a Browns fan is its own Badwater: an intentional immersion in futility, an intellectual exercise in not giving up, a barrel meandering across the Atlantic, a communal fast where enlightenment is promised but only another off season rebuild is delivered. We elect it. We embrace it. We carry it on our backs.

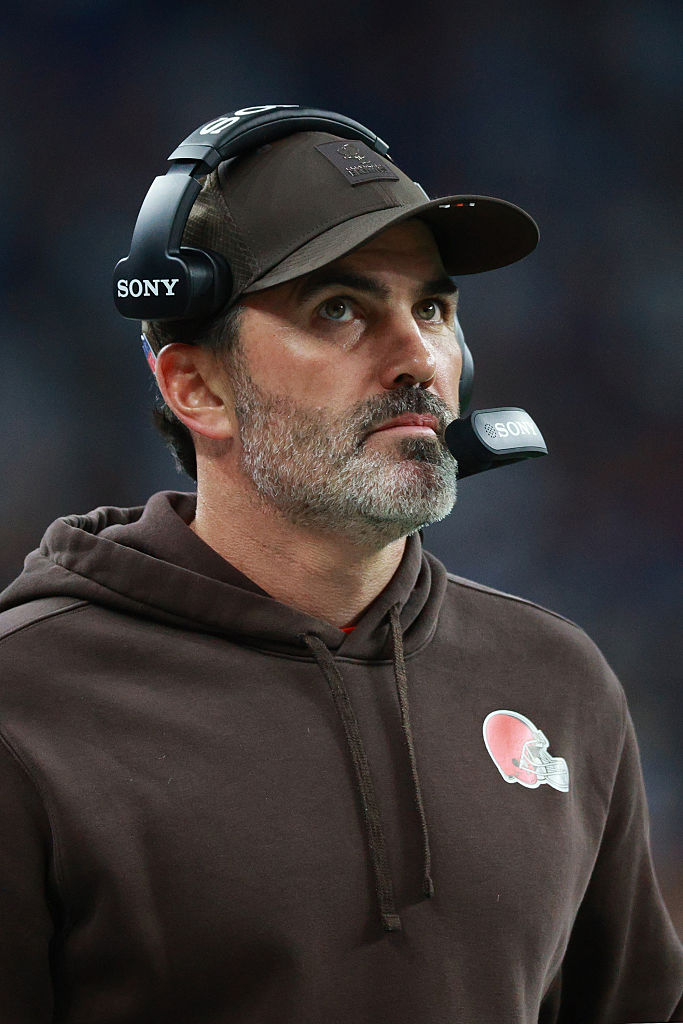

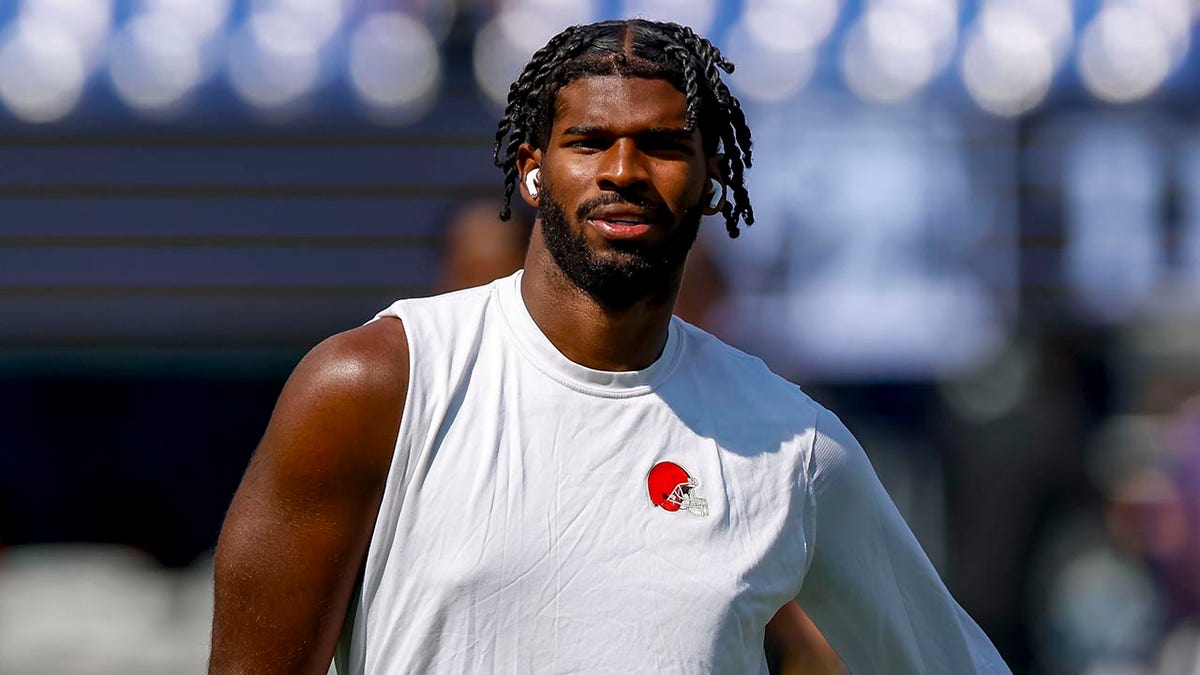

Consider the résumé: In the 1990s, the Browns were kidnapped to Baltimore, where they promptly won a Super Bowl while wearing someone else’s laundry. Since their return, Cleveland has managed only one playoff win. In the 2010s, we perfected a 1–31 stretch, capped by the platonic ideal of defeat: a 0–16 season. Just a few days ago, at our home opener, the Browns lost by one point to the Bengals. Since 2000, we’ve enjoyed just four winning seasons. The Colts, in their Peyton years, won relentlessly, but the stadium felt like a country club brunch; just last week they were voted the most pessimistic fans. The Rams won a Super Bowl in 2021, but half their stadium was visiting fans. Cleveland’s fans, by contrast, fill a losing stadium with the raw energy of a religious revival every single home game, in rain, snow, or sleet.

This is not “despite” our record. I am starting to believe that it is because of it. The resilience is the point.

A few hours have passed, and I am writing now sitting down in a patch of dirt by a creek, eating granola out of a bag. My legs ache, my back is striped with bruises, and an hour ago I sprinted in my underwear after a camping chair that the wind had blown downstream. I am suffering, but not unhappily. I feel fully at peace. I’ve gone through extreme lengths, and I rest brimming with a feeling of ability; not to accomplish, but to endure. Pain is proof that I can carry more than I thought. Misery is evidence of capacity. My partner sits beside me, just as sore, just as odorous. There is companionship in this misery. There is a triumph in the resilience of suffering, together. There really is an art to that.

And that is Cleveland football. We climb the mountain season after season, battered and bruised, hauling futility on our backs. And though the summit reveals nothing more than another mountain, we keep going, together.

Our losing seasons are not a failure but a kind of fellowship. They are a ritual, a proving ground, a daily reminder that endurance itself is a victory. There really is an art to suffering. In Cleveland, we practice it together with devotion – shotgunning warm beers in the Muni Lot, cheering through the wind and snow, and finding joy where no one else would dare look.

Being a Browns fan is not about wins. It is about endurance. It is about carrying futility like a pack on your back and still walking forward, shoulder to shoulder with thousands who feel the same bruises, the same sting of disappointment. We do not suffer in silence. We revel in it, we ritualize it, we turn loss into communion. In Cleveland, misery is not defeat; it is proof. Proof that we can endure, that we can keep climbing, that we can find joy in the climb itself. And maybe, just maybe, that is the closest any of us will ever come to enlightenment.

Subscribe to Cleveland Scene newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed