Opening day, April 10, 1915, at Washington Park, on Third Avenue between 1st and 3rd Streets in Park Slope, Brooklyn. The Brooklyn Tip-Tops (seen in white uniforms) won but finished the season in seventh place out of eight teams.

Photo: Library of Congress, Bain Collection

It was always a city game, baseball.

For all the efforts to slap a pastoral gloss on the sport, for all the attempts to make it about little boys playing in a cow pasture, only someone unfamiliar with the isolation of American farm life could truly believe that baseball came of age in the country.

What we think of as baseball today is really an urban game. More precisely, it is “the New York game.” That’s what modern baseball was first called, and where it was first played. New York is where its rules were perfected, and where we first kept score. New York was where the curveball was devised, and the bunt, and the stolen base, and where the home run came into its own. New York was where admission was first charged to see a game, and where the very first all-star game was played, and the first “world championship.”

It was in New York, too, where the game’s color line was finally broken, and the reserve clause was made law, and where a players’ league was conceived, and died, and where the first, modern free agent was signed. It was here that the sport’s — or any sport’s — first true superstar emerged, and where the first true baseball stadiums were built. Where sportswriting came into its own, where the first great radio broadcasters plied their trade, and where the first game was televised. It was in New York that the only perfect game in World Series history was pitched, where an expansion team won a World Series for the first time, where 14 World Series were played exclusively within the city limits—and where the World Series was fixed by gamblers.

Baseball is a game that grew up inextricably linked to the pace, and the customs, and the demands of New York. It was shaped by the challenges and the possibilities the city had to offer, by its inventiveness and its ambitions, its grandiosity and its corruption. For the last two centuries, the game’s trajectory has followed the city’s many rises and declines, its booms and its busts, its follies and its tragedies.

It is not the intention here to enter into the eternal debate over exactly when and where the very first contest involving a bat and a ball took place. Claimants range from Prague to Pittsfield, and just about every burg in between. As David Block notes in Baseball Before We Knew It, ancient hieroglyphics depict Egyptians with bats playing at something called seker-hemat, around 2500 B.C. Berbers in the 1930s were observed playing ta kurt om el mahag, or “the ball of the pilgrim’s mother” — a game one historian theorized was brought to North Africa in the fifth century A.D. by the Vandals, who were credited in turn with inventing the ancient, Northern European game of “longball.” Medieval Normans played grande théque, while their French cousins played la balle empoisonée, the Germans had schlagball, and the Finns played pesapällo.

Countless other bat-and-ball games evolved under any number of different rules and different names in England. There was hand-in and hand-out, and wicket and cricket, and rounders. There was prisoner’s base, or just “base”; there was tip-cat and one-old-cat; there was feeder, and squares, and northern spell; there was stool-ball, and stobball or stow-ball, and trap ball, and tut-ball; and there was goal ball, barn ball, sting ball, soak ball, stick ball, and burn ball; and round-ball and town ball, and finally — baseball (or base-ball, or base ball).

The whole welter of English and continental games followed the colonists over to America. On Christmas Day, 1621, Governor William Bradford of Plymouth Colony was enraged to find some of his fellow Pilgrims, “frolicking in ye street, at play openly; some at pitching ye barr, some at stoole ball and shuch-like sport.” At Valley Forge, George Washington was recorded as having taken part in a game of “wicket,” while Lewis and Clark tried to teach a form of “base” to the Nez Perce, and small boys wrote later of watching a grown Abe Lincoln join in their games of town ball: “… how long were his strides, and how his coat-tails stuck out behind, and how we tried to hit him with the ball, as he ran the bases. He entered into the spirit of play as completely as any of us, and we invariably hailed his coming with delight.”

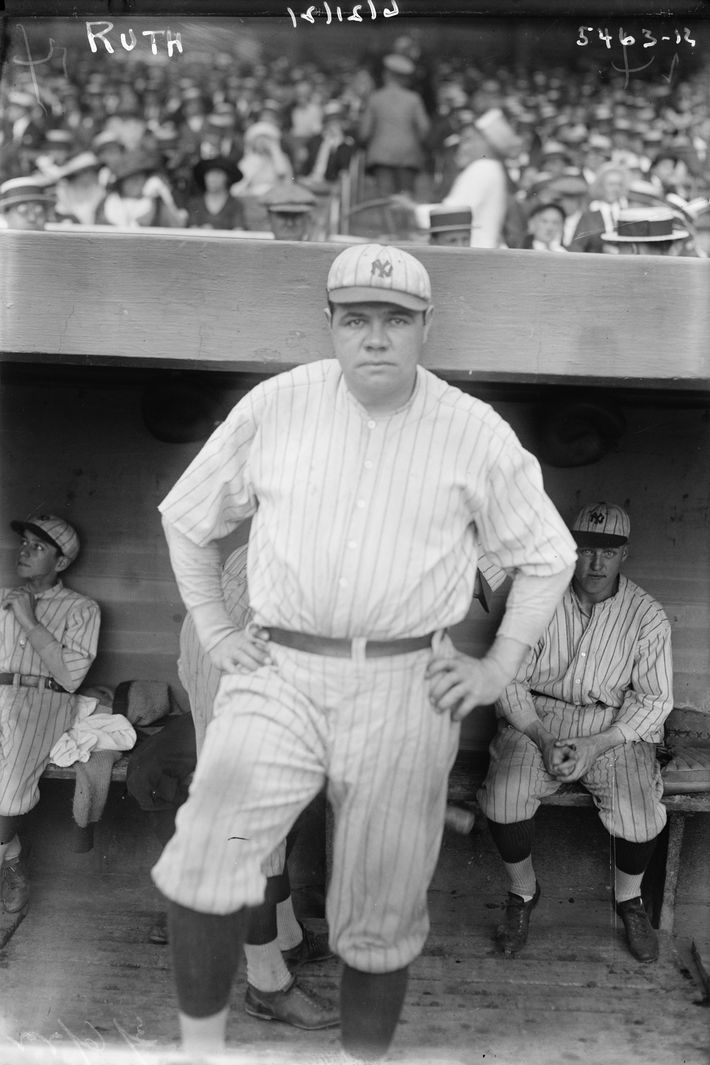

The first true superstar sports celebrity: Babe Ruth of the New York Yankees.

Photo: Library of Congress

The one thing that is clear is that Abner Doubleday had nothing to do with it. This was widely acknowledged even at the time the myth was first propagated, by a Special Base Ball Commission, handpicked by Albert Spalding in 1905. Spalding, one of the game’s earliest stars turned team-owner-and-sporting-goods-magnate, was eager to refute the thesis of his friend, Henry Cartwright, that baseball had evolved from the English girls’ game of rounders. Certain that such antecedents would not serve for the pastime of a young, proud nation just emerging on the world stage, Spalding’s commission seized instead upon the weakest reed imaginable. This was a letter sent by an aged Western crank named Abner Graves, who would murder his wife in a fit of senile paranoia a few years later. Graves swore that he had seen Doubleday lay out the whole game one afternoon in 1839 along the banks of the Glimmerglass, in Cooperstown, New York, and that was good enough for the chairman of Spalding’s commission, A.G. Mills.

Abner Doubleday was the Forrest Gump of the 19th century, a soldier, mystic, and bibliophile with an uncanny ability for being on hand when anything of interest was going on. The first shot of the Civil War, a Confederate cannon blast at Fort Sumter, “penetrated the masonry and burst very near my head,” he later recalled, and in turn he “aimed the first gun on our side in reply to the attack.” He would rise to the rank of major general, sustain two serious wounds, hold the Union line on the first day of Gettysburg, and take the train back to Pennsylvania with President Lincoln, when the president gave his Gettysburg Address. Doubleday read Sanskrit, corresponded with Ralph Waldo Emerson, commanded an all-Black regiment of troops, attended séances at the White House with Mary Todd Lincoln, obtained the first charter for San Francisco’s cable cars, and served as president of Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society … but he did not invent baseball.

Nobody really thought he did, even on Spalding’s commission. A.G. Mills had been friends with Doubleday for 20 years, including a period when Mills was president of the National League. A fellow Civil War officer, Mills had arranged Doubleday’s funeral and his burial at Arlington Cemetery. Yet for as long and as well as he knew him, Mills admitted, he never heard his friend so much as mention baseball. In a brief autobiographical sketch, Doubleday himself wrote that, “In my outdoor sports, I was addicted to” — drumroll, please — “topographical work …”

Just why anyone took Graves’s claim seriously in the first place is something of a mystery. One of the game’s greatest historians, John Thorn, speculates that this may have come about thanks to feuding factions of Theosophists, who for a time included Spalding. If true, it’s hilarious. Theosophy was an early mix of new age religion, occultism, and spiritualism. It’s as if a group of feuding Scientologists hatched a plot to have L. Ron Hubbard replace Dr. Naismith as the inventor of basketball.

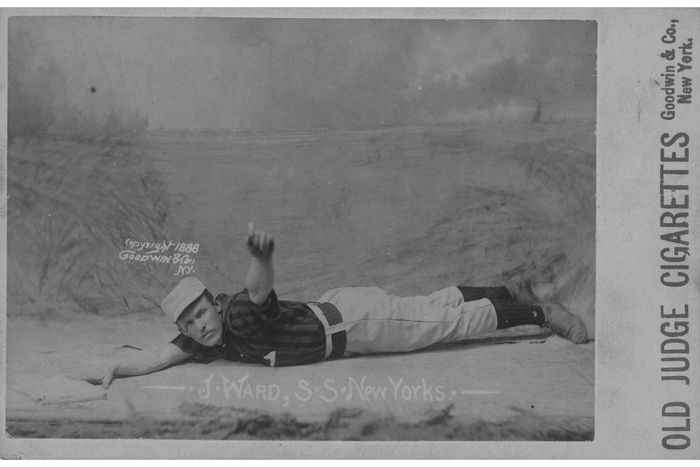

John Montgomery Ward, who started the Players’ League to compete with the National and American Leagues in 1890. It didn’t last.

Photo: Library of Congress

Confronted by reporters years later, Mills fumfahed that his commission had only concluded “that the first baseball diamond was laid out in Cooperstown.” This was also untrue, but Mills revealed another reason for his commission’s determined gullibility. That is, the need to move the national game out of the clutches of the dirty, immigrant city:

“I submit to you gentlemen, that if our search had been for a typical American village, a village that could best stand as a counterpart of all villages where baseball might have been originated and developed — Cooperstown would best fit the bill.”

And so it would. Though of all the great stars, and the makers of the game that the charming National Baseball Hall of Fame would admit, they would not include … Abner Doubleday.

By the 1950s, an alternative foundation myth had been set in place, one revolving around how, one fine day in 1846, the New York Knickerbockers Base Ball Club took the steam ferry over to the Elysian Fields, a pleasure park just across the Hudson from Manhattan in Hoboken, to play the mysterious “New York Base Ball Club” in the very first game of “real” baseball — and got plastered, 23-1. I never understood this one even when I first read about it as an 8-year-old boy. If the Knickerbockers invented the damned game, how did they manage to lose the first one so badly?

The truth, of course, is that they weren’t the first. The Knickerbockers were just one of at least six early baseball clubs that by 1846 had already existed for years in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Their chief contribution, as Thorn puts it, was as “consolidators rather than innovators,” combining and formalizing rules that others were already playing by. “The Knickerbocker Rules” became “the New York Game,” and by the Civil War it had pretty much wiped out every other form of bat-and-ball game in the country.

Photo: Penguin Random House

Baseball became “America’s game,” as Walt Whitman called it, with “the snap, go, fling of the American atmosphere …” For Mark Twain it was, “The very symbol, the outward and visible expression of the drive and push and rush and struggle of the raging tearing, booming 19th century.”

But more than America’s game, baseball was New York’s game. It held its own in a town where the other leading spectator sports were rat-baiting, bare-knuckle boxing, and firefighting (The city’s volunteer fire companies used to brawl with each other for the honor of putting out the town’s incessant conflagrations.). The sport came of age in a city that often seemed hell-bent on its own destruction. A city where not just firefighters fought with each other, but rival police departments did, too, and on the steps of City Hall. Where commuter steamboats raced and exploded in the Hudson, and teamsters whipped and cursed each other as they raced their wagons in the streets. A city prone to riot and mayhem at the drop of a rumor, an island ringed by tanneries, slaughterhouses, knacker’s yards and rendering plants, bucket shops and block-and-fall joints.

Baseball was played anywhere the space could be found, on empty lots and in the streets, on what had just yesterday had been garbage dumps, pig styes, mud flats, and even river bottoms. It was played not just by gentlemen in pleasure gardens, but by men of every background and description. By Black men and white, Hispanic and Irish — of all classes and professions. There were teams composed solely of shipbuilders, firefighters, actors, postal clerks, bank clerks, ferrymen, newspaper reporters and printers’ devils, government bureaucrats, and ministers. There were the Manhattans, a club made up of policemen; and the Phantoms, who were bartenders, and the Pocahontas Club, who were all milkmen. There were the Metropolitans, who were schoolteachers, and the Columbia club of Orange, New Jersey, who were hatters, and the Aesculapeans of Brooklyn, who consisted entirely of eye doctors.

Almost from the start, too, the game drew gamblers and touts, ward heelers and con artists, adoring groupies, and loutish “bugs” or “kranks,” as the fans were then known. It was a tough game played in a tough town, and right away, many New Yorkers, especially money men and fixers, politicos and promoters, saw the main chance in it just as they did in everything else. They, too, would contribute much to making the game what it became, the first major team sport in the world.

From The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City, by Kevin Baker. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Kevin Baker.

.jpg)

.jpg)