Tag: Artemis Program

-

Hydrogen leaks delay Artemis II moon mission until March

[ad_2]

Source link -

Artemis II moon rocket fueling test scrubbed due to hydrogen leaks

After working around a hydrogen leak, NASA pressed ahead with a “wet dress” rehearsal countdown of its Artemis II moon rocket Monday, loading the huge rocket with more than 750,000 gallons of liquid oxygen and hydrogen fuel, only to be derailed by additional leakage early Tuesday.

Already running several hours behind schedule, the countdown resumed at the T-minus 10-minute mark around 12:09 a.m. EST Tuesday, ticking down toward a simulated engine start.

But four-and-a-half minutes later, the countdown stopped again due to a “liquid hydrogen leak at the interface of the tail service mast umbilical, which had experienced high concentrations of liquid hydrogen earlier in the countdown,” NASA said on social media.

The Space Launch System rocket’s mobile launch platform is equipped with two tail service masts, large side-by-side structures at the base of rocket that house propellant lines leading to pull-away umbilical assemblies on a side of the booster’s engine compartment.

“The launch control team is working to ensure the SLS rocket is in a safe configuration and (to) begin draining its tanks,” NASA said.

Whether mission managers will be able to clear the rocket for launch as early as Sunday to propel four astronauts on a flight to the moon will depend on the results of a detailed overnight review and post-test analysis. But NASA only has three days — Feb. 8, 10 and 11 — to get the mission off this month or the flight will slip to March.

Hydrogen leaks have proven extremely difficult to repair at the launch pad, and a Super Bowl Sunday launch appears unlikely unless managers conclude the leak is manageable as is. But no final decisions on a path forward are expected until engineers have a chance to review the data. A news briefing is expected at 1 p.m. Tuesday.

The practice countdown began Saturday evening — two days late because of frigid weather along Florida’s Space Coast and, after a meeting Monday morning to assess the weather and the team’s readiness to proceed, Launch Director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson cleared engineers to begin the remotely-controlled fueling operation.

The test got underway about 45 minutes later than planned but initially appeared to be proceeding smoothly as supercold liquid oxygen and hydrogen fuel were pumped into the Space Launch System rocket’s first stage tanks. Shortly after, hydrogen began flowing into the rocket’s upper stage as planned.

But after the first stage hydrogen tank was about 55 percent full, a leak was detected at an umbilical plate where a fuel line from the launch pad is connected to the base of the SLS rocket’s first stage. After a brief pause, engineers resumed fuel flow but again cut it off with the tank about 77 percent full.

After more discussion, they decided to press ahead on the assumption the leak would decrease once the tank was full and in a replenishment mode when flow rates were reduced. And that turned out to be the case.

“NASA teams have completed filling the core stage of the SLS rocket with liquid hydrogen,” NASA said in a brief web update at 4:45 p.m. “Engineers continue to watch the leak at the interface of the tail service mast umbilical, but the liquid hydrogen concentration in the umbilical remains within acceptable limits.”

The countdown was timed for a simulated launch at 9 p.m. EST, but the test ran longer than originally planned. As of 9:55 p.m., the countdown was in an extended hold at the T-minus 10-minute mark. The count finally resumed just after midnight, only to be stopped a final time at T-minus five minutes and 15 seconds.

NASA

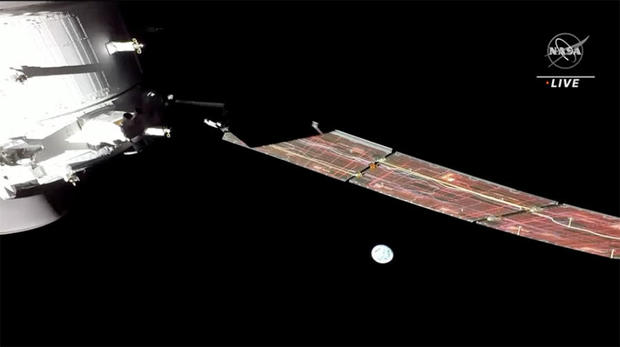

The SLS is the rocket NASA plans to use to send Artemis astronauts to the moon aboard Orion crew capsules. It is the most powerful operational launcher in the world, a towering 332-foot-tall rocket powered by two strap-on solid fuel boosters and four main engines burning liquid oxygen and hydrogen fuel that generate 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff.

Artemis II commander Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch and Jeremy Hansen are hoping to launch atop the SLS rocket as early as Sunday night for a nine-day two-hour flight around the moon and back. They planned to fly to Florida Tuesday to begin final preparations, but that will depend on the results of the countdown review.

The SLS rocket’s first and so far only mission came in 2022, when it was launched on an unpiloted test flight. In the campaign leading up to launch, engineers ran into a variety of problems ranging from fuel leaks to unexpected propellant flow behavior in the launch pad’s plumbing. Launch was delayed for months while engineers worked to resolve the problems.

For the rocket’s second launch, multiple upgrades and improvements were implemented and Blackwell-Thompson said she was optimistic the fueling test would go well.

“Why do we think that we’ll be successful? It’s the lessons that we learned,” she said last week.

“Artemis I was the test flight, and we learned a lot during that campaign, getting to launch,” she said. “And the things that we learned relative to how to go load this vehicle, how to load LOX (liquid oxygen), how to load hydrogen, have all been rolled in to the way in which we intend to load the Artemis II vehicle.”

Most of the fixes and upgrades appeared to work as planned. But leakage at the tail service mast umbilical, a problem during the first Artemis flight in 2022, cropped up again the second time around.

-

Returning to the moon: An overview of the Artemis Program and Artemis II

THE CHARGES THAT SHE’S NOW FACING THIS MORNING. WESH TWO NEWS STARTS NOW WITH BREAKING NEWS. THAT BREAKING NEWS JUST INTO WESH TWO NEWS AND OUR NEWSROOM. NASA IS CONFIRMING THE EARLIEST POSSIBLE LAUNCH OF THE ARTEMIS TWO MISSION IS NOW BEING PUSHED TO SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 8TH. IF THAT DATE RINGS A BELL, IT’S BECAUSE IT’S SUPER BOWL SUNDAY. THE AGENCY DIDN’T START THE ROCKET’S WET DRESS REHEARSAL LAST NIGHT. THAT’S DUE TO COLD WEATHER CONDITIONS, SO IT WILL NOW ATTEMPT THE REHEARSAL ON MONDAY, AND THEN THE LAUNCH DATE AND TIME WILL BE FINALIZED. ONCE TEAMS HAVE REVIEWED THE RESULTS OF THE WET DRESS REHEARSAL. AND WE’RE ALSO STAYING ON TOP OF

Returning to the moon: An overview of the Artemis Program and Artemis II

Updated: 10:38 AM EST Jan 30, 2026

Latest updates on Artemis IIJan. 30: ‘Wet dress rehearsal’ delayed due to weatherJan. 28: Cold weather puts wet dress rehearsal in questionJan. 17: NASA rolls out Artemis II at Kennedy Space CenterArtemis II is preparing for launch from the Kennedy Space Center, where the rocket will carry the Orion spacecraft for a second time, this time with a crew on its journey to the moon.The first launch window opens from Feb. 6-11. If it does not launch in February, there will be another window open in March, and again in April if necessary.>> WESH 2 will stream the launch live in this article The mission aims to test the spacecraft’s systems with astronauts aboard before future lunar landings. The 10-day flight aims to help confirm systems and hardware NASA needs for early human lunar exploration missions.According to NASA, four astronauts will venture around the moon on Artemis II, paving the way for a return to the Moon and eventually Mars.The hope is to establish a long-term presence for future exploration and science through the Artemis Program. The science conducted in space is expected to drive progress in medicine and technology on Earth. As the mission prepares for launch, the crawler transporter moved the Artemis II rocker from the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center on Jan. 17, bringing it to launch pad 39-B. “It’s been since 1972 that human beings have gone anywhere in the vicinity of the moon,” said Dr. Don Platt from Florida Tech. A crew of four astronauts will be aboard NASA’s Space Launch System.Commander: Reid WisemanPilot: Victor GloverMission Specialist: Christina KochMission Specialist: Jeremy Hansen The four astronauts will launch aboard NASA’s Space Launch System rocket and travel inside the Orion spacecraft to fly around the moon. In space, they will test critical systems needed for future moon landings. Artemis Program overviewArtemis is NASA’s long-term Moon exploration campaign.The program’s main goals include returning humans to the moon, building a sustained lunar presence, maturing technology and operations needed for human missions to Mars, and doing this all with international and commercial partners.The missions are each designated to different milestones, strategies and individual goals.Artemis IThis mission is complete.It was an uncrewed integrated flight test of the Space Launch System, which is a heavy-lift rocket that launches crews and large cargo toward the moon, and Orion, which is a crew spacecraft that carries astronauts to lunar orbit and returns them to Earth.SLS and Orion went around the moon and came back to Earth.The purpose of this mission was to validate deep-space performance and reentry before flying with a crew.>> Relive the launch of Artemis I here. Aretmis IIThis mission is planned.Artemis II will be the first crewed mission to the moon.The purpose of the crewed flight is to prove life support, operations and high-speed returns with astronauts. Artemis IIIThis mission is planned.Artemis III will be the first crewed lunar landing of the program, targeting the lunar South Pole region.The 10-day mission will include field geology, sample collection/return and deployed experiments.Four astronauts will launch in Oroin, two will land on the moon for surface work, and then they will return to Orion for the journey back to Earth. Artemis IV and beyondThe future missions will aim to expand on capabilities toward sustained operations on the moon, such as more surface time, more cargo and infrastructure delivery, increased use of Gateway as a staging node, and progression toward an “Artemis Base Camp” style sustainable presence. Why the lunar South Pole?It has scientifically valuable terrain and ancient geology.It contains regions with water ice and other volatiles in permanently shadowed areas, which is key for science and potential resources.Its challenging conditions will help prove the systems needed for Mars-class missions. More information Best Central Florida locations to view the launchIn Volusia CountySouth side of New Smyrna Beach (Canaveral National Seashore)Bethune Beach, 6656 S. Atlantic Ave.Apollo Beach at New Smyrna BeachIn Brevard County (the Space Coast)Jetty Park Beach and Pier, 400 Jetty Park Road, Port Canaveral. (There’s a charge to park.) Space View Park, 8 Broad St., TitusvilleAlan Shepard Park, 299 E. Cocoa Beach Causeway, Cocoa BeachCocoa Beach Pier, 401 Meade Ave. (Parking fee varies.)Lori Wilson Park, 1400 N. Atlantic Ave., Cocoa BeachIn Vero BeachAlma Lee Loy Bridge in Vero BeachMerrill Barber Bridge in Vero Beach

Latest updates on Artemis II

Jan. 30: ‘Wet dress rehearsal’ delayed due to weather

Jan. 28: Cold weather puts wet dress rehearsal in question

Jan. 17: NASA rolls out Artemis II at Kennedy Space Center

Artemis II is preparing for launch from the Kennedy Space Center, where the rocket will carry the Orion spacecraft for a second time, this time with a crew on its journey to the moon.

The first launch window opens from Feb. 6-11. If it does not launch in February, there will be another window open in March, and again in April if necessary.

>> WESH 2 will stream the launch live in this article

The mission aims to test the spacecraft’s systems with astronauts aboard before future lunar landings. The 10-day flight aims to help confirm systems and hardware NASA needs for early human lunar exploration missions.

According to NASA, four astronauts will venture around the moon on Artemis II, paving the way for a return to the Moon and eventually Mars.

The hope is to establish a long-term presence for future exploration and science through the Artemis Program. The science conducted in space is expected to drive progress in medicine and technology on Earth.

As the mission prepares for launch, the crawler transporter moved the Artemis II rocker from the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center on Jan. 17, bringing it to launch pad 39-B.

“It’s been since 1972 that human beings have gone anywhere in the vicinity of the moon,” said Dr. Don Platt from Florida Tech.

A crew of four astronauts will be aboard NASA’s Space Launch System.

- Commander: Reid Wiseman

- Pilot: Victor Glover

- Mission Specialist: Christina Koch

- Mission Specialist: Jeremy Hansen

The four astronauts will launch aboard NASA’s Space Launch System rocket and travel inside the Orion spacecraft to fly around the moon. In space, they will test critical systems needed for future moon landings.

Artemis Program overview

Artemis is NASA’s long-term Moon exploration campaign.

The program’s main goals include returning humans to the moon, building a sustained lunar presence, maturing technology and operations needed for human missions to Mars, and doing this all with international and commercial partners.

The missions are each designated to different milestones, strategies and individual goals.

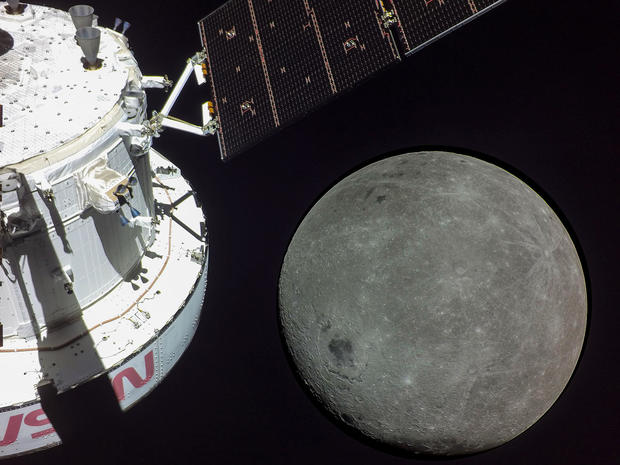

Artemis I

- This mission is complete.

- It was an uncrewed integrated flight test of the Space Launch System, which is a heavy-lift rocket that launches crews and large cargo toward the moon, and Orion, which is a crew spacecraft that carries astronauts to lunar orbit and returns them to Earth.

- SLS and Orion went around the moon and came back to Earth.

- The purpose of this mission was to validate deep-space performance and reentry before flying with a crew.

>> Relive the launch of Artemis I here.

Aretmis II

- This mission is planned.

- Artemis II will be the first crewed mission to the moon.

- The purpose of the crewed flight is to prove life support, operations and high-speed returns with astronauts.

Artemis III

- Artemis III will be the first crewed lunar landing of the program, targeting the lunar South Pole region.

- The 10-day mission will include field geology, sample collection/return and deployed experiments.

- Four astronauts will launch in Oroin, two will land on the moon for surface work, and then they will return to Orion for the journey back to Earth.

Artemis IV and beyond

- The future missions will aim to expand on capabilities toward sustained operations on the moon, such as more surface time, more cargo and infrastructure delivery, increased use of Gateway as a staging node, and progression toward an “Artemis Base Camp” style sustainable presence.

Why the lunar South Pole?

- It has scientifically valuable terrain and ancient geology.

- It contains regions with water ice and other volatiles in permanently shadowed areas, which is key for science and potential resources.

- Its challenging conditions will help prove the systems needed for Mars-class missions.

More information

Best Central Florida locations to view the launch

In Volusia County

- South side of New Smyrna Beach (Canaveral National Seashore)

- Bethune Beach, 6656 S. Atlantic Ave.

- Apollo Beach at New Smyrna Beach

In Brevard County (the Space Coast)

- Jetty Park Beach and Pier, 400 Jetty Park Road, Port Canaveral. (There’s a charge to park.)

- Space View Park, 8 Broad St., Titusville

- Alan Shepard Park, 299 E. Cocoa Beach Causeway, Cocoa Beach

- Cocoa Beach Pier, 401 Meade Ave. (Parking fee varies.)

- Lori Wilson Park, 1400 N. Atlantic Ave., Cocoa Beach

In Vero Beach

- Alma Lee Loy Bridge in Vero Beach

- Merrill Barber Bridge in Vero Beach

-

NASA hauls Artemis II moon rocket to launch pad for February flight

After months of meticulous preparation, NASA’s 32-story-tall Space Launch System rocket, the most powerful operational booster in the world, was hauled to its seaside launch pad Saturday in Florida, setting the stage for a long-awaited flight next month to send four astronauts on a trip around the moon.

The 5.7-million-pound rocket, carried by an upgraded Apollo-era crawler-transporter tipping the scales at some six million pounds, began the trip to pad 39B just after 7 a.m. local time, creeping out of NASA‘s cavernous Vehicle Assembly Building at a top speed of just under 1 mile per hour.

William Harwood/CBS News

Hundreds of space center workers, family members and guests gathered near the VAB and along the crawlerway to take in the sight, posing for selfies and enjoying a chilly Saturday morning as the towering moon rocket slowly rolled past.

New NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman and the Artemis II astronauts — Cmdr. Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch and Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen — were also on hand to witness the milestone.

“Wow. LETS GO!!!” Wiseman posted on the social media platform X with a photo of the SLS rocket moving out of the VAB. In another post, he called the SLS and its Orion crew capsule “engineering art.”

Generating some 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff, the SLS is the most powerful rocket ever operated by NASA, including the agency’s legendary Saturn 5 moon rocket. It has a little more than half the thrust of SpaceX’s Super Heavy-Starship rocket, but after a successful unpiloted test flight in 2022 — Artemis I — NASA deemed it safe enough to put astronauts aboard.

The SpaceX rocket is still in the test phase, and it’s not known when it might make its first flight with people on board.

NASA

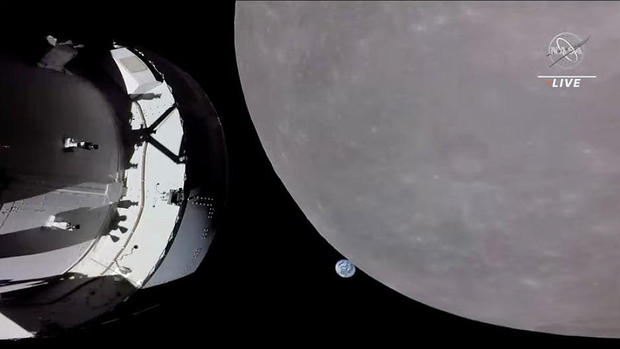

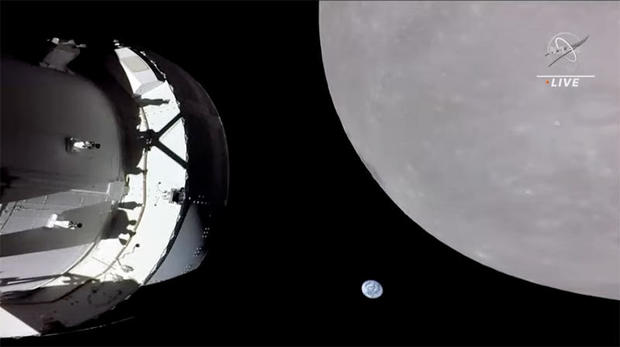

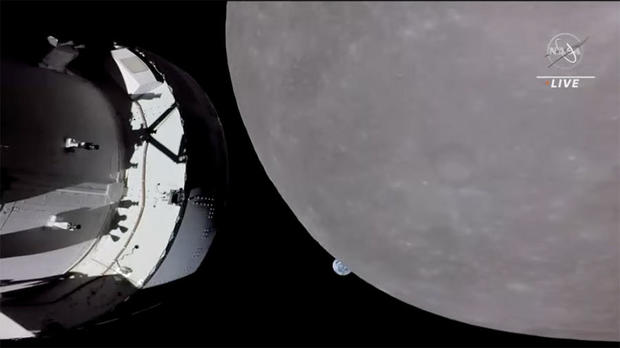

The Artemis II crew plans to blast off in early February to test drive their Orion crew capsule in Earth orbit before heading into deep space on a flight around the moon that will carry them farther from Earth than any astronauts have ever ventured. In the process, they will get a chance to observe the far side of the moon in some detail.

“I think one of the most magical things for me in this experience is when I looked out a few mornings ago, there was a beautiful crescent (moon) in the morning sunrise, and I truly just see the far side,” Wiseman told reporters during the SLS rollout. “It was a waning crescent here, so it’s a waxing gibbous on the far side.”

He added: “And you just think about all the landmarks we’ve been studying on that far side, and how amazing that will look, and seeing Earth rise, those sorts of things, just flipping the moon over and seeing it from the other perspective is what I think when I look out (at the moon) right now.”

The trip to launch pad 39B took about eight hours, kicking off a busy few weeks of tightly scripted tests and checkouts before a critical fueling test around Feb. 2 when nearly 800,000 gallons of super cold liquid hydrogen and oxygen will be pumped aboard for a “wet” dress rehearsal countdown.

“One of the first things that happens after we get to the pad, we get connected … all the validations, getting tied back to the firing room, getting ready to power up the individual elements,” said launch director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson. “We will get into our crew module work (and) we’re going to power everything up.”

Blackwell-Thompson added: “We have incrementally tested all of this offline or in the integrated environment of the VAB and now it’s just getting out to the pad and testing those pad interfaces. … Wet dress is the big test at the pad. That’s the one to keep an eye on, I guess, that’s the driver to launch.”

CBS News

The maiden flight of the SLS rocket in 2022 was delayed multiple times by propellant loading problems and persistent hydrogen leaks. For the rocket’s second flight, NASA and its contractor team have implemented multiple upgrades and procedural changes to minimize or eliminate any such problems the second time around.

“Artemis I was a test flight, and we learned a lot during that campaign getting to launch,” said Blackwell-Thompson. “And the things that we learned relative to how to go load this vehicle, how to load (liquid oxygen), how to load hydrogen, have all been rolled into the way in which we intend to load the Artemis II vehicle.”

Because of the relative positions of the Earth and moon, along with the trajectory NASA plans to use for Artemis II, the agency only has five launch opportunities in February: Feb. 6, 7, 8, 10 and 11. Because rollout came a few days later than planned, pushing the fueling test into early February, it would appear only the final three opportunities are still available.

But a leak-free fueling test, in the absence of any other major issues, will clear the way for a launch attempt on one or two of those days. If not, the next set of launch windows opens in March.

A wild card in the mission planning is the launch of a fresh crew to the International Space Station to replace four crew members who returned to Earth ahead of schedule Thursday because of a medical issue affecting one of the astronauts. That launch originally was scheduled for Feb. 15, but NASA managers are looking into moving it up by several days to minimize the gap between crews.

NASA flight controllers want to avoid flying two piloted spacecraft at the same time. If the space station crew replacement flight stays on track, or if problems are found during the SLS fueling test, agency managers might be forced to delay the Artemis II launch to the next set of opportunities in March.

But Isaacman is keeping NASA’s options open.

“We have, I think, zero intention of communicating an actual launch date until we get through wet dress,” he said. “But look, that’s our first window, and if everything is tracking accordingly, I know the teams are prepared, I know this crew is prepared. We’ll take it.”

-

NASA juggling piloted moon mission and space station crew replacement flight

With a space station medical evacuation safely completed, NASA is focused on two challenging missions proceeding in parallel: launching four astronauts on a flight around the moon, at the same time as the agency is planning to send four replacement astronauts to the International Space Station.

Engineers plan to haul the Artemis 2 moon rocket to launch pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center on Saturday for tests leading to launch early next month on a historic piloted flight around the moon.

NASA/Keegan Barber

At the same time, NASA is gearing up to launch four Crew 12 astronauts to the space station, possibly while the Artemis 2 moon mission is underway, to replace four Crew 11 crew members who cut their mission short and returned to Earth ahead of schedule Thursday because of a medical issue.

The Artemis 2 mission and Crew 12’s planned space station flight present a unique challenge for NASA. The agency has not managed two piloted spacecraft at the same time since a pair of two-man Gemini capsules tested rendezvous procedures in low-Earth orbit in 1965. The agency has never flown a deep space mission amid another launch to Earth orbit.

“This is exactly what we should be doing at NASA,” Jared Isaacman, NASA’s new administrator, said Thursday. “We have the means as an agency … to be able to bring our astronauts home at any time … while making preparations to pull forward our next mission, like Crew 12, while also progressing on our Artemis 2 campaign.”

He described the moon mission as “probably one of the most important human spaceflight missions in the last half century.”

The world’s most powerful rocket booster

NASA’s towering 322-foot-tall Space Launch System rocket, the most powerful operational booster in the world, will be hauled out of the cavernous Vehicle Assembly Building early Saturday atop an upgraded Apollo-era crawler transporter. Including at least one stop along the way, the 4-mile move to the pad is expected to take eight to 10 hours.

“It takes us a little while to get out of the building,” said Launch Director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson. “But about an hour after we get that first motion, you’ll begin to see that beautiful vehicle cross over the threshold of the VAB and come outside for the world to have a look.”

Once at the pad, engineers will carry out a variety of tests and work to ready the rocket and its Orion crew capsule for blastoff early next month on the Artemis 2 moon mission.

“It really doesn’t get much better than this,” John Honeycutt, chairman of the Artemis 2 Mission Management Team, told reporters Friday. “We’re making history.”

Commander Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch and Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen planned to be on hand for the rollout. If all goes well, the crew will test the Orion capsule in Earth orbit before heading into deep space, flying farther from home than any other humans as they loop around the far side of the moon.

Artemis 2 mission plan

The Artemis 2 mission follows a similar flight in 2022 that sent an unpiloted Orion capsule around the moon to pave the way for next month’s flight. The Artemis 2 mission, in turn, will set the stage for Artemis 3, a long-awaited and oft-delayed mission to land astronauts near the moon’s south pole. The current target date for Artemis 3 is 2028.

Despite Saturday’s planned rollout, the Artemis 2 launch date is still uncertain.

It will depend in large part on the results of a fueling test around the first of the month when engineers plan to load the booster’s 21-story-tall first stage with 733,000 gallons of super-cold liquid hydrogen and oxygen along with a full load of propellants for the booster’s 45-foot-tall second stage, the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, or ICPS.

NASA/Frank Michaux

During tests of the SLS rocket used for the Artemis 1 mission in 2022, multiple fueling tests had to be carried out before engineers finally resolved a series of propellant leaks. The SLS rolling out on Saturday features multiple upgrades and improvements to minimize or eliminate any such leakage.

If the upcoming fueling test goes well, Wiseman and his crewmates could be cleared to blast off a few days before Feb. 11, the end of next month’s launch period. If any major problems are found during the propellant loading exercise, Artemis 2 likely will slip to early March when the next set of launch windows becomes available.

Next space station crew

Amid the work to ready the Artemis 2 rocket for launch, NASA managers are also working to move up the launch of the Crew 12 space station crew. Commander Jessica Meir, Jack Hathaway, European Space Agency Sophie Adenot and cosmonaut Andrey Fedyaev are officially scheduled for launch on Feb. 15.

The crew they are replacing, Crew 11 commander Zena Cardman, Mike Fincke, Japanese astronaut Kimiya Yui and cosmonaut Oleg Platonov, originally expected to return to Earth around Feb. 20 after helping familiarize their replacements with the intricacies of space station operation.

NASA/Bill Ingalls

But Crew 11 was ordered to cut their mission short after one of the crew members developed a medical issue of some sort. They returned to Earth Thursday, leaving just three people aboard the space station: cosmonaut Sergey Kud-Sverchkov, Sergey Mikaev and NASA astronaut Chris Williams. They were launched to the outpost in November aboard a Russian Soyuz spacecraft.

NASA and SpaceX are working to move up the Crew 12 launch date to minimize the gap between the two NASA missions. Depending on where it ends up, NASA could be orchestrating a launch to the International Space Station while the Artemis 2 crew is flying around the moon.

“I don’t see any reason why we wouldn’t continue along those parallel paths,” Isaacman said. “And if it comes down to a point in time where we have to de-conflict between two human spaceflight missions, that is a very good problem to have at NASA.”

Jeff Radigan, lead flight director for Artemis 2, agreed it made sense to continue preparing for both missions.

“I know the agency is preparing to launch Crew 12,” he told reporters. “There are a lot of preparations going on, but there absolutely are constraints.”

“It’s not prudent for us to put both of those up at the same time, but we also have to ensure that both of them are ready to go. We may run into an issue, and the last thing we want to do is make a decision too early and then lose an opportunity. That would not be responsible of us.

“So, we need to keep pressing with both missions, we need to ensure that we’re doing that at the right speed, and we’re looking at the right technical constraints. As we get closer, either the decision will come about because the hardware’s talking to us and we have an issue that we have to go deal with, or we have to pick one.”

But, he added, “that doesn’t mean we should stop preparing for either mission right now, but we need to do that at the right pace.”

-

Astronauts complete practice countdown for upcoming trip around the moon

Four astronauts in training to fly around the moon early next year strapped into their Orion spacecraft this weekend for a dress rehearsal countdown in a major milestone toward launch.

Based on repeated stops and starts seen on NASA’s countdown clock, the complex test originally planned for late November, ran into problems at various points on Saturday. NASA provided no details, but Artemis 2 commander Reid Wiseman said that overall, the test went well.

NASA

“Extremely successful day in our spacecraft #Integrity,” Wiseman said in a post on X. “Did everything go perfectly? Absolutely not. But this vehicle and our team showed us they’re up to the challenge. Launch is getting very close.”

Launch is tentatively targeted for early February, but the schedule is extremely tight and the flight may slip to early March. No decisions are expected until after the first of next year.

In any case, Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch and Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen, wearing bright orange pressure suits, strapped into their Orion capsule using the same procedures they’ll follow on launch day.

Such “countdown demonstration tests” have traditionally taken place shortly before launch with the rocket and crew ship already on the launch pad. But for Saturday’s test, the astronauts boarded their spacecraft atop NASA’s huge Space Launch System (SLS) rocket inside the cavernous Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center.

NASA

Over the course of the exercise, the astronauts and the launch control team worked through the same countdown procedures they will follow on launch day, ending less than a minute before the clocks would normally hit zero.

Five launch opportunities are available in February when the moon and Earth are in the proper relative positions. The first such opportunity comes on Feb. 6. To make that date, the SLS rocket and Orion would have to be rolled from the assembly building to pad 39B in mid January, setting the stage for a critical fueling test that must go well before NASA can proceed to launch.

Given the amount of work remaining to complete preparations, sources say NASA may opt to delay the flight to early March.

Whenever it takes off, the flight plan calls for the Orion and its crew to spend 25 hours in an elliptical orbit around Earth to test spacecraft life support, propulsion and navigation systems.

The crew plans to fly in close proximity to the SLS rocket’s upper stage to test the Orion’s maneuvering systems and rendezvous procedures that will be needed for eventual moon landing missions.

An uncrewed Orion carried out a similar loop around the moon during the Artemis 1 mission in November 2022. But the Lockheed Martin-built spacecraft was not equipped with a full life support system and it did not carry out thruster firings like those needed for a rendezvous.

Once the testing is complete, the Artemis 2 Orion will leave Earth orbit on a “free return” trajectory that will carry the crew around the moon and back to a Pacific Ocean splashdown. The ship will not go into orbit around the moon.

But Artemis 2 will still be the first piloted trip back to the moon since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972, carrying Wiseman and his crewmates farther from Earth than any other humans have ever traveled.

NASA

The flight will set the stage for Artemis 3, carrying yet-to-be-named astronauts to the surface of the moon near the lunar south pole, NASA hopes, in 2028.

The Artemis 3 flight originally was planned for 2024, a target set during the first Trump administration. But the mission has been repeatedly delayed by processing problems, slowdowns during the COVID pandemic, Super Heavy-Starship testing and work to develop the lunar lander, known by NASA as the Human Landing System, or HLS.

The current 2028 target was set in the past few weeks when it became apparent the space agency would not be ready in time for the most recent previous target of 2027.

China also plans to land its own “taikonauts” on the moon by 2030, creating a new space race of sorts, one that NASA vows to win.

-

NASA introduces 10 new astronaut candidates

NASA on Monday introduced 10 new astronauts, four men and six women selected from more than 8,000 applicants, to begin training for future flights to the International Space Station, the moon and, eventually, Mars.

“One of these 10 could actually be one of the first Americans to put their boots on the Mars surface, which is very, very cool,” Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy, and NASA’s acting administrator, said in welcoming remarks.

“No pressure, NASA, we have some work to do,” he said.

Josh Valcarcel – NASA – JSC

Meet the astronauts

This is NASA’s first astronaut class with more women than men. It includes six pilots with experience in high-performance aircraft, a biomedical engineer, an anesthesiologist, a geologist and a former SpaceX launch director.

Among the new astronaut candidates is 35-year-old Anna Menon, a mother of two who flew to orbit in 2024 aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon as a private astronaut on a commercial, non-NASA flight.

“I am so thrilled to be back here with the NASA family,” Menon said. “As more and more people venture into space … we have this awesome opportunity to learn a tremendous amount to help support those astronauts … and help keep them healthy and safe. So it’s an exciting time to be here.”

Menon worked for NASA for seven years as a biomedical researcher and flight controller before joining SpaceX in 2018. She served as a senior engineer and was later selected as the onboard medical officer during the commercial Polaris Dawn mission, chartered by billionaire Jared Isaacman.

Josh Valcarcel – NASA – JSC

She married her husband Anil in 2016 while both were working for NASA. A former Air Force flight surgeon, Anil Menon joined SpaceX as its first medical officer in 2018. He joined NASA’s astronaut corps in 2021 and is now assigned to a long-duration space station crew scheduled for launch aboard a Russian Soyuz next summer.

Anna and Anil Menon are among several couples who served in the astronaut corps at the same time. But only one couple ever flew in orbit together — shuttle astronauts Mark Lee and Jan Davis in 1992.

The other members of the 2025 astronaut class are:

- Army Chief Warrant Officer 3 Ben Bailey, 38, a graduate of the Naval Test Pilot School with more than 2,000 hours flying more than 30 different aircraft, including recent work with UH-60 Black Hawk and CH-47F Chinook helicopters.

- Lauren Edgar, 40, who holds a Ph.D. in geology from the Caltech, with experience supporting NASA’s Mars exploration rovers and, more recently, serving as a deputy principal investigator with NASA’s Artemis 3 moon landing mission.

- Air Force Maj. Adam Fuhrmann, 35, an Air Force Test Pilot School graduate with more than 2,100 hours flying F-16 and F-35 jets. He holds a master’s degree in flight test engineering.

- Air Force Maj. Cameron Jones, 35, another graduate of Air Force Test Pilot School as well as the Air Force Weapons School with more than 1,600 hours flying high performance aircraft, spending most of his time flying the F-22 Raptor.

- Yuri Kubo, 40, a former SpaceX launch director with a master’s in electrical and computer engineering who also competed in ultimate frisbee contests.

- Rebecca Lawler, 38, a former Navy P-3 Orion pilot and experimental test pilot with more than 2,800 hours of flight time, including stints flying a NOAA hurricane hunter aircraft. She was a Naval Academy graduate and was a test pilot for United Airlines at the time of her selection.

- Imelda Muller, 34, a former undersea medical officer for the Navy with a medical degree from the University of Vermont College of Medicine; she was completing her residency in anesthesia at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore at the time of her astronaut selection.

- Navy Lt. Cmdr. Erin Overcash, 34, a Naval Test Pilot School graduate and an experienced F/A-18 and F/A-18F Super Hornet pilot with 249 aircraft carrier landings. She also trained with the USA Rugby Women’s National Team.

- Katherine Spies, 43, a former Marine Corps AH-1 attack helicopter pilot and a graduate of the Naval Test Pilot School with more than 2,000 hours flying time. She was director of flight test engineering for Gulfstream Aerospace Corp. at the time of her astronaut selection.

The new astronaut candidates will spend two years training at the Johnson Space Center and around the world with partner space agencies before becoming eligible for flight assignments.

NASA

Astronauts join space race in uncertain times

The new astronauts are joining NASA‘s ranks at a time of great uncertainty given the Trump administration’s budget cuts, plans to retire the ISS at the end of the decade and challenges faced by the agency’s Artemis moon program.

Under the Trump administration’s planned budget cuts, future NASA crew rotation flights have been extended from six months to eight, reducing the total number of flights through the end of the program. In addition, crew sizes are expected to be reduced.

It’s not clear how many of the new astronauts might be able to fly to the ISS before it’s retired or how many might eventually walk on the moon. Whether NASA can get there before the Chinese, who are targeting the end of the decade for their own moon landing mission, is also uncertain.

SpaceX/NASA

But Duffy assured the new astronaut candidates that NASA will, in fact, beat China back to the moon.

“Some are challenging our leadership in space, say, like the Chinese,” he said. “And I’ll just tell you this: I’ll be damned if the Chinese beat NASA or beat America back to the moon. We are going to win … the second space race back to the moon, with all of you participating in that great effort.”

As for flights to Mars, which the Trump administration supports, flights are not yet on the drawing board and most experts say no such NASA mission is likely to launch within the next decade and probably longer.

-

SpaceX scrubs Super Heavy-Starship’s 10th test flight again due to weather

SpaceX for a second day scrubbed the test launch of its huge Super Heavy-Starship rocket, this time due to weather conditions.

It was expected to be the program’s 10th test flight on Monday, a milestone mission to put corrective upgrades through their paces after three catastrophic failures earlier this year.

A successful flight would help restore confidence in the gargantuan rocket amid growing concern a moon lander variant being built for NASA may not be perfected in time for a planned 2027 landing and possibly not before the Chinese mount their own piloted moon mission at the end of the decade.

But in the near term, SpaceX’s goal was to get the Super Heavy-Starship flying again after multiple back-to-back failures.

A launch attempt Sunday was called off because of trouble with a ground system at the company’s Starbase flight test and manufacturing facility on the Texas Gulf Coast. But that problem was quickly corrected and blastoff was reset for 7:30 p.m. ET Monday.

The goals of the flight were to test the Super Heavy first stage under a variety of stressful flight conditions, deliberately shutting engines down during descent to splashdown in the Gulf to make sure it can handle real failures during an actual mission.

RONALDO SCHEMIDT/AFP via Getty Images

Given the nature of the tests, SpaceX ruled out a dramatic return to the launch pad for a mid-air capture by giant mechanical arms on the support gantry.

As for the Starship, the flight plan called for sending the upper stage halfway around the world on a sub-orbital trajectory to a controlled re-entry and splashdown in the Indian Ocean.

Along the way, a variety of tests were planned, including the deployment of eight Starlink simulator satellites and an in-space restart of a methane-fueled Raptor engine. Modified heat shield tiles were in place and a few were even removed to determine the effects of extreme re-entry temperatures on the rocket’s structure.

Multiple upgrades also were in place to minimize the chances of propellant leaks, fires and engine shutdowns like those that led to the loss of the last three Starships launched, none of which was able to complete its mission.

RONALDO SCHEMIDT/AFP via Getty Images

While a successful test flight this time around might ease concerns about the viability of the Super Heavy-Starship for future moon missions, it’s unlikely to eliminate them.

The moon lander variant will use most of its propellant just to reach low-Earth orbit. For a flight to the moon, SpaceX will have to launch 10 to 20 Super Heavy-Starship tanker flights in rapid succession to top off the lander’s tanks. A single failure would almost certainly require a mission restart.

And even if SpaceX’s achieves the required launch cadence, no one has ever attempted cryogenic propellant transfers on that scale in orbit.

And there is no flight-proven technology to minimize, if not eliminate, the otherwise unavoidable loss of propellants as the super-cold liquids naturally warm in space, boiling off and turning into gas that must be vented overboard.

Most observers believe SpaceX will eventually overcome the hurdles ahead. The question is, can the vehicle be perfected in time for a 2027 moon landing?

Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy, NASA’s acting administrator, is optimistic SpaceX will be ready to fly.

“If you look at the company as a whole and past performance, they often times are behind, and then all of a sudden, they make these massive leaps forward,” he said in an interview with CBS News. “I would be hard pressed to say they’re not going to meet the goals and the timelines.”

“Their leadership has said we feel very confident that we are going to be ready for the mission,” he said. “And so I’ll take them at their word.”

CBS News interviewed multiple current and former NASA and contractor managers and engineers in recent weeks who unanimously agreed a landing in 2027 could not be safely carried out with the current architecture.

And not one of them said they believed NASA could get there before the Chinese without a drastic change of course.

“I think the folks you’ve talked to are accurate. We are not going to go ahead and get a crewed Starship to the moon by 2030, under any circumstances,” said a senior engineer who worked on the Artemis program.

“That doesn’t mean they’ll never get there. That doesn’t mean the architecture couldn’t work. But it’s just too big of a technical leap to accomplish in the short time that we’ve got.”

But as Duffy pointed out, SpaceX has chalked up a remarkable record with its partially reusable Falcon family of rockets, launching them at an unmatched pace that allows the company to rapidly implement and test upgrades and fixes.

As of Friday, SpaceX had launched 518 Falcon 9s and 11 triple-core Falcon Heavy rockets with just two in-flight failures. The company has successfully recovered first-stage boosters 490 times.

Given its record, many fans give SpaceX the benefit of the doubt when it comes to the Super Heavy-Starship. But the giant rocket dwarfs the Falcon 9, and the requirements for a successful moon landing are well beyond those faced in a typical satellite launcher.

“My concerns have to do with how complicated the mission architecture is, how many flights there are to send a single lander to the moon,” said Douglas Cooke, a retired 38-year NASA veteran who now does consulting work for Boeing and other aerospace concerns.

“Getting into the high numbers,” he added, “reduces the probability of success.”

SpaceX did not respond to a request for comment.

-

SpaceX launches private-sector lunar lander on trail-blazing flight to the moon

Lighting up the deep overnight sky, a Falcon 9 rocket thundered away from Florida early Thursday, boosting a commercially built robotic lander on a flight to the moon. If successful, it will become the first American spacecraft to reach the lunar surface in more than 50 years.

It was SpaceX’s second flight in less than eight hours, following launch of six U.S. Space Force missile detection and tracking satellites earlier in the day, and the third launch to orbit worldwide counting a Russian space station cargo ship that took off from Kazakhstan.

SpaceX

Launch of another Falcon 9 carrying a batch of 22 Starlinks, this one at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, was called off without explanation.

But the Florida moonshot brought a busy day in space to a spectacular conclusion with a picture-perfect liftoff at 1:05 a.m. EST Thursday, five weeks after another commercial lander built by Pittsburg-based Astrobotic suffered a mission-ending malfunction.

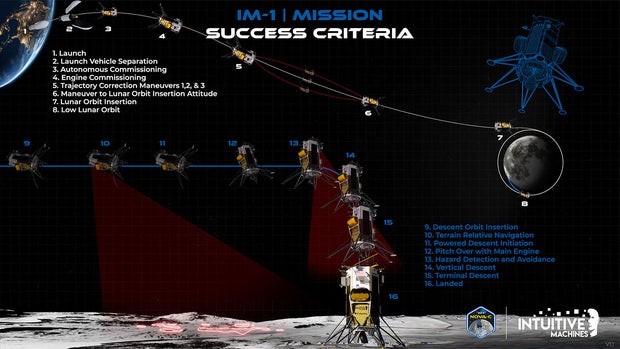

Thursday’s launching went off without a hitch, and Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus lander was released to fly on its own 48 minutes after liftoff. If all goes well, the spacecraft will brake into orbit around the moon and descend to the surface next Thursday, touching down about 186 miles from the moon’s south pole.

Partially funded by NASA, the flight is a trail blazer of sorts for the agency’s Artemis program, which plans to send astronauts to the moon’s south polar region in the next few years. NASA instruments aboard Odysseus will study the lunar environment and test needed technologies for downstream missions.

To reach its landing site, Odysseus will rely on a high-power 3D-printed main engine burning liquid oxygen and methane propellants, a first for a deep space mission. Problems loading the lander with properly chilled methane forced SpaceX to order a 24-hour launch delay, but there were no known issues Thursday.

Odysseus carries six NASA instruments and another six commercial payloads, including sculptures, proof-of-concept cloud storage technology, insulation blankets provided by Columbia Sportswear and a student-built camera package that will drop to the surface ahead of the lander to photograph its final descent.

Among the NASA experiments is an instrument to study the charged particle environment at the moon’s surface, another that will test navigation technologies and downward-facing stereo cameras designed to photograph how the lander’s engine exhaust disrupts the soil at the landing site.

Intuitive Machines

Also on board: an innovative sensor that will use radio waves to accurately determine how much cryogenic propellant is left in a tank in the weightless environment of space, technology expected to prove useful for future moon missions and other deep space voyages.

Odysseus and its experiments are expected to operate for about a week on the moon’s surface before the sun sets at the landing site, cutting off solar power. The spacecraft is not designed to survive the extreme low temperatures of the two-week lunar night.

Only the United States, Russia, China, India and Japan have successfully put landers on the surface of the moon, and Japan’s membership in that exclusive club comes with an asterisk: its “SLIM” lander tipped over on touchdown Jan. 19 and failed to achieve all of the mission’s objectives.

Three privately funded moon landers were launched between 2019 and this past January, one from an Israeli non-profit, one from a Japanese company and Astrobotic’s ill-fated Peregrine. All three failed.

Peregrine and Odysseus were both funded in part by NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, or CLPS (pronounced CLIPS), designed to encourage private industry to develop transportation capabilities that NASA can then use to transport payloads to the moon.

The agency’s goal is to help kickstart development of new technologies and to collect data that will be needed by Artemis astronauts planning to land near the moon’s south pole later this decade.

The agency spent about $108 million for its part in the Peregrine mission and another $129 million for the Odysseus instruments and transportation to the moon.

Intuitive Machines

“These aren’t NASA missions, they’re commercial missions,” said Susan Lederer, CLPS project scientist at the Johnson Space Center. “These commercial companies will be bringing our instruments along for the ride, enabling our investigations by providing power, data and (communications) to us.

“With the commercial industry comes a competitive environment, which means that our investment up front ultimately gets far more for far less. So instead of one mission in a decade, it allows for more like 10 commercial missions to the moon in a decade.”

The Intuitive Machines launch capped a busy day for SpaceX.

At 5:30 p.m., a Falcon 9 rocket blasted off from pad 40 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station carrying four Space Development Agency missile tracking satellites and two hypersonic threat detection satellites for the Missile Defense Agency.

William Harwood/CBS News

The two MDA satellites are designed to continuously track ultra-high-speed missiles or other threats, handing off to other satellites or ground systems for targeting. They will work in the same orbit as the SDA tracking satellites to help planners assess how threats can be managed at multiple levels.

The four SDA tracking satellites were the final members of a 27-satellite constellation fielded by the SDA in “tranche 0” of its “proliferated warfighter space architecture.” Additional satellites will be launched in the next few years to populate additional tranches, or constellations of increasingly capable spacecraft.

The $4.5 billion U.S. Space Force program aims to deploy hundreds of small laser-linked tracking and data relay satellites distributed in multiple constellations and orbital planes to provide global coverage that is less vulnerable to attack.

With the Space Force flight safely on its way, SpaceX engineers on the West Coast attempted to launch 22 Starlink internet satellites from Vandenberg Space Force Base northwest of Los Angeles. But SpaceX called off that flight at the end of its launch window.

On the other side of the planet at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, Russian engineers launched the Progress MS-26/67P cargo ship at 10:25 p.m. EST, kicking off a two-day flight to the International Space Station.

The Progress is loaded with 5,500 pounds of cargo, including 3,258 pounds of dry goos, 1,279 pounds of space station propellant and 926 pounds of water. Docking at the station’s Zvezda module is expected at 1:26 a.m. EST Saturday.

-

Japanese flight controllers re-establish contact with tipped-over SLIM moon lander

Japanese flight controllers re-established contact with the robotic SLIM lunar lander Saturday, eight days after the spacecraft tipped over and lost power as it was touching down on Jan. 19, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency announced Sunday.

An engine malfunction moments before landing caused the Smart Landing for Investigating (the) Moon, or SLIM, spacecraft to drift to one side during its final descent instead of dropping straight down to the surface.

That lateral velocity apparently caused the probe to tilt over as it touched down, leaving its solar cells, attached to the top of the lander, facing away from the sun. Without solar power, the spacecraft was forced to rely on the dwindling power in its on-board battery.

JAXA

After downloading a few photographs and collecting as much engineering data as possible, commands were sent to shut the spacecraft down while it still had a small reserve of battery power.

At the time, officials said they were hopeful contact could be restored when the angle between the sun and SLIM’s solar cells changed as the moon swept through its orbit.

In the meantime, NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter photographed the SLIM landing site last week from an altitude of 50 miles, showing the spacecraft as a tiny speck of reflected light on the moon’s cratered surface:

No details were immediately available Sunday, but the team said in a post on X that it “succeeded in establishing communication with SLIM last night and have resumed operations! We immediately started scientific observations with MBC (multi-band camera), and have successfully obtained first light.”

The target was a nearby rock formation nicknamed “toy poodle.”

It was not immediately known if enough power was available to recharge SLIM’s battery, how long engineers expected the spacecraft to operate with the available power or whether it might be shut down again to await additional power generation.

Despite its problems, SLIM successfully landed on the moon, making Japan the fifth nation to pull off a lunar landing after the United States, the former Soviet Union, China and India

Three commercially developed robotic landers launched over the last few years from Japan, Israel and the United States all suffered malfunctions that prevented intact landings.

A fourth commercial lander, built by Houston-based Intuitive Machines, is scheduled for launch next month.

-

New Vulcan rocket blasts off on maiden flight carrying privately built robotic moon lander

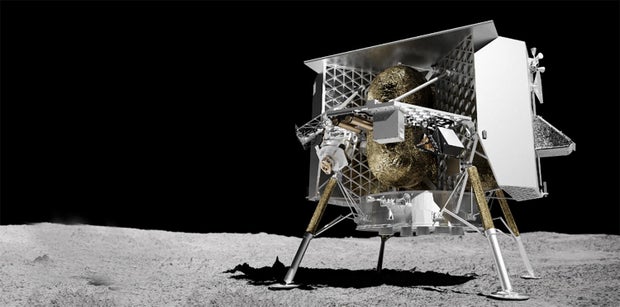

For the first time in more than 50 years, a commercially built American lander was fired off to the moon early Monday, a small robotic probe called Peregrine that’s packed with 20 experiments and international payloads, including five NASA science instruments and a sensor valued at $108 million.

Other payloads include university experiments, a collection of Mexican and U.S. micro rovers, artwork, compact time capsules, a bitcoin and even a small collection of human “cremains” provided by two companies that offer memorial flights to space.

While the Peregrine lander, built by Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic, was the mission’s showcase payload, its ride to space was equally important, if not moreso: the long-awaited maiden flight of United Launch Alliance’s new Vulcan rocket, a heavy-lift booster that’s replacing the company’s workhorse Atlas and Delta family of launchers.

William Harwood/CBS News

After a surprisingly problem-free countdown, the Vulcan’s two methane-burning BE-4 engines and twin solid-propellant strap-on boosters thundered to life at 2:18 a.m. EST, lighting up the deep overnight sky with a brilliant burst of fire and billowing clouds of exhaust.

The 198-foot-tall, 1.5-million-pound rocket majestically climbed skyward from launch complex 41 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station atop two million pounds of thrust, quickly arcing away to the east over the Atlantic Ocean in a sky-lighting spectacle visible across central Florida

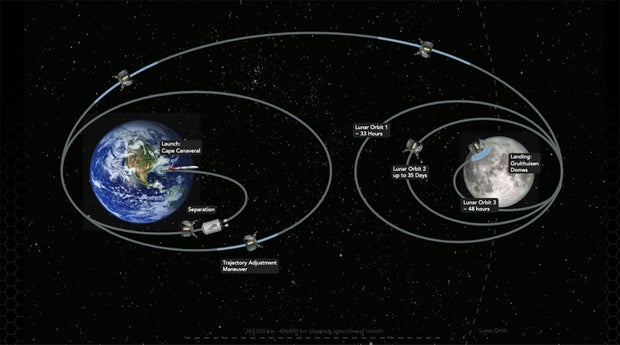

The flight plan called for the Peregrine lander to be released into a highly elliptical Earth orbit. The spacecraft is expected to spend about 18 days in that orbit before firing its thrusters to head for the moon.

After loitering in a low-altitude circular orbit while waiting for sunrise at the landing site, the spacecraft will begin its descent on Feb. 23, targing touchdown near an enigmatic volcanic feature known as the Gruithuisen Domes.

“It’s hard to put into words how excited Astrobotic is for making this first mission back to the surface of the Moon since Apollo,” said CEO John Thornton. “This is a moment 16 years in the making. We’ve had to overcome a lot along the way, a lot of doubt.

“When we started in Pittsburgh, the idea of building a space company, much less one to go to the moon, was completely foreign and alien, and folks literally laughed at the concept. But 16 years later … here we are on the launch pad.”

Along with adding a powerful new rocket to the U.S. inventory, the launch was the first in a series of private-sector moon missions funded under a NASA program intended to spur development of commercial lunar transportation and surface delivery services.

NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program or CLPS, “will usher in not only great new science for NASA in the United States, but the first test of this new model where it’s not NASA’s mission, NASA is being carried to the surface of the moon as part of a commercial mission with a commercial launch vehicle,” said Joel Kearns, a senior CLPS manager.

As for the Vulcan, Mark Peller, ULA’s vice president of Vulcan development, said “it’s the future of our company.”

Astrobotic

“The system that we’ve developed is really positioning us for a very bright, prosperous future for many, many years to come,” he said. “It has proven to already be an extremely competitive product in the marketplace, having an order book of over 70 missions before first flight.”

Replacing the company’s expensive Delta 4 and workhorse Atlas 5 rocket, which uses Russian RD-180 Russian engines, the Vulcan relies on two BE-4 first stage engines built by Blue Origin, the space company owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

At liftoff, the twin BE-4s generate 1.1 million pounds of thrust. Two Northrop Grumman strap-on solid-propellant boosters, or SRBs, generate another 919,200 pounds of push, providing a total thrust of just over 2 million pounds. The Vulcan can be launched with up to six strap ons depending on mission requirements.

The new rocket also features a more powerful hydrogen-fueled Centaur upper stage with two Aerojet Rocketdyne RL10C engines capable of boosting heavy military payloads into so-called high-energy orbits that can’t be easily reached by rockets optimized for low-Earth orbit.

“No one in the world still designs a high-energy-optimized rocket,” ULA CEO Tory Bruno told a small group of reporters at the launch pad Saturday. “That market has been abandoned by the commercial providers because it’s less expensive (and) less risky to develop rockets designed for LEO (low-Earth orbit) operations.”

“Not only is it very, very capable, it’s also less expensive,” he added, saying a Vulcan costs about one third the price of a Delta 4 Heavy.

SpaceX now dominates the commercial launch marketplace, firing off a record 96 Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy flights last year, not counting two partially successful test flights of the company’s new Super Heavy-Starship. Sixty three of the Falcons launched in 2023 were used to put the company’s Starlink internet satellites into orbit.

Astrobotic

Peller said the Vulcan is an “extremely good value and is very competitive in the marketplace.”

“What’s unique about Vulcan, and what we originally set out to do, was to provide a rocket that had all the capabilities of Atlas and Delta in one single system,” he said. “And we achieved that in a vehicle that has performance that’s even greater than the three-body Delta 4 Heavy.

“What we’ve been able to achieve is a vehicle that goes all the way from medium to heavy lift in a single core configuration. Unlike Delta 4 (and) some of our competitors, where they have to use three-body configuration vehicles for heavy lift, Vulcan can do that all in a single core.”

As for SpaceX’s gargantuan Super Heavy-Starship, Bruno called it “an extreme example of a LEO-optimized rocket. So a veritable freight train to LEO. I mean, I’ll be straight with you guys, a Starship, when successfully fielded, will carry four times the mass that (Vulcan) can carry to LEO.”

But he said the fully reusable Starship uses all its fuel just to reach low-Earth orbit. “That’s why they talk about on-orbit refueling because it’s dry once it gets there,” he said, adding, “it’ll be an excellent platform for carrying Starlinks.”

Maiden flights typically feature small, relatively inconsequential payloads because of presumably higher risks. But Astrobotic opted to put Peregrine atop the first Vulcan because of ULA’s long history, its record of successful launches and because the Vulcan, other than the BE-4 engines, is essentially an upgraded version of the flight-proven Atlas 5.

“We chose United Launch Alliance as first flight of Vulcan because we believe so much in the company, and we’re very, very confident that this mission will be successful,” Thornton said. “And of course, that came with some relief on the price, and that makes this mission possible.”

Only the United States, Russia, China and India have successfully put landers on the surface of the moon. If successful, Peregrine will be the first U.S. lander to reach the moon’s surface since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972, the first privately developed American lander and only the third overall.

Two privately funded moon landers, one from Israel and the other from Japan, crashed during landing attempts in 2019 and 2023 respectively.

Peregrine is designed to serve as a lunar delivery vehicle, carrying payloads from governments, universities, nonprofits and even individuals to the surface of the moon. Astrobotic’s website says the cost to put a payload into orbit around the moon is $300,000 per kilogram (2.2 pounds). The price for a landing is $1.2 million per kilogram.

NASA put five sophisticated instruments on Peregrine Mission 1, along with a space navigation sensor. The agency’s total investment in the mission is $108 million.

Other payloads include five micro rovers provided by Mexico, an experimental Astrobotic navigation sensor, a Japanese time capsule with messages from more than 185,000 children, bitcoins, a small rover from Carnegie Mellon University, commemorative plaques and a DHL “Moonbox” containing a variety of mementos, including a tiny rock from Mount Everest.

Also on board: samples of cremated remains provided by Celestis and Elysium Space, companies that offer to send small amounts of ashes of loved ones into space as memorials.

The president of the Navajo Nation recently told NASA the presence of human remains of any sort aboard spacecraft landing on the moon amounts to desecration of a celestial body that is “revered by our people.” NASA officials said they were willing to discuss the concerns, but the Peregrine launch was expected to proceed as planned.

“I’ve been disappointed that this conversation came up so late in the game, I would have liked to have this conversation a long time ago,” Thornton said. “We announced the first payload manifest of this nature back in 2015, a second in 2020. We really are trying to do the right thing, and I hope we can find a good path forward with Navajo Nation.”

-

Artemis 2 astronauts on seeing their Orion moonship for the first time: “It’s getting very, very real”

NASA’s four Artemis 2 astronauts this week got their first look at the Orion capsule that will carry them around the moon next year. The astronauts said seeing the hardware firsthand — and meeting the men and women building the spacecraft — brought home the reality of their historic mission.

“It’s starting to feel very, very real,” Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen told reporters Tuesday, standing with his crewmates in front of the Orion capsule. “It’s not a dream. It’s a program. It’s real hardware.”

“Yesterday, we spent a lot of time meeting other teams on site, and (seeing) just how much work there is to do, and how hard they’re working…They’re grinding it out over the next year and a half or so to try and take us back to the moon for the first time in over 50 years,” Hansen added.

William Harwood/CBS News

Hansen, Artemis 2 commander Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover and Christina Koch were named to the crew in April, but their visit to the Kennedy Space Center Monday and Tuesday was their first chance to see their spacecraft.

“When we first stuck our heads in and you look around in there, you realize this can only be one thing, a spaceship,” Koch said. “Nothing else looks like that, and that’s exactly what it felt like. That’s what gave me shivers. We were playing ‘name that item.’ Honestly, we were looking around, we were trying to marry it up with everything we learned about in our technical classes.”

Said Wiseman: “We’re fired up. It’s a great day when you walk around the corner at the Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout facility and there’s your spacecraft that you’re going to ride in — ‘the ship,’ as they call it (here). And we got we got to look inside and hang out, and it was really quite fascinating.”

The current schedule shows Wiseman and company launching in November 2024. They will not orbit or land on the moon, but instead will put the Orion capsule through its paces during three orbits of Earth, including one with a high point of 38,000 miles, before heading out on a free-return trajectory around the moon and back to a Pacific Ocean splashdown.

William Harwood/CBS News

NASA is still officially targeting December 2025 for the first actual lunar landing, when an Orion capsule will carry four astronauts to the moon. Two of them will board a waiting SpaceX lander, a variant of the company’s Starship rocket, and descend to the surface. But it’s an open question whether the lander will be ready in time.

Jim Free, director of NASA’s exploration division, said the agency recently discussed the schedule with engineers at SpaceX’s “Starbase” flight test facility near Boca Chica, Texas, where the company is gearing up for a second test flight of the Super Heavy booster and Starship upper stage. The first test flight on April 20 ended in failure, reaching an altitude of just 24 miles after multiple premature engine shutdowns.

To get to the moon, the Starship lander will need to be robotically refueled in low-Earth orbit, requiring multiple Super Heavy-Starship “tanker” flights. Before NASA will know whether a 2025 astronaut landing is feasible, Free said SpaceX will need to launch enough successful flights to demonstrate reliability, carry out ship-to-ship refueling and then stage an unpiloted lunar landing.

“We were at Starbase a couple of weeks ago, and really spent some time going through their major milestones to the Artemis 3 mission, which includes a (propellant) transfer mission as well as the uncrewed demo,” he said. “We’ll look at that and update around that in the near future. But what we’re holding all the contractors to is that December of ’25 date.”

If the schedule slips out too far, “we may end up flying a different mission,” he added. That presumably could mean a lunar orbit mission for Artemis 3 instead of a moon landing if the Starship isn’t ready, or some other major problem crops up.

NASA

“We may end up flying a different mission if we have these big (delays), we’ve looked at can we can we do other missions if the possibility exists there,” Free said. “But right now, we’re still trying to look at their schedule.”

As for the Artemis 2 mission, Free said the Orion capsule, its European-built service module and the Space Launch System rocket are all on track for launch by the end of 2024. The pacing item, he said, is analysis of the heat shield that protected the Artemis 1 Orion during its high-speed return to Earth after an unpiloted maiden test flight last December.

The heat shield experienced uneven charring and erosion during its high-temperature re-entry, and while the Orion capsule was not damaged, engineers are carrying out tests to better understand why the heat shield did not behave as expected.

“I think it’s definitely the biggest open issue,” Free said. But, he added, “I think we’re on a path to that root cause with the final disposition in April.”

“Obviously, we’re going to make the right decision to keep them safe,” he said. “If that decision is we have to do something drastic, then we’ll do that. But right now, we’re on a path to get to the root cause, and then we’ll make the final determination from there. “

-

Maybe We Shouldn’t Go Back To The Moon After All

Humans are going back to the Moon! NASA’s Artemis program is going to send a bunch of astronauts to the Lunar surface in the coming years, initially for Moon business, but later to start work on the eventual journey to Mars. It’s exciting stuff, but as this art series shows, it can’t hurt to pack a few extra pieces of…

Luke Plunkett

Source link -

NASA announces crew for first trip back to the moon in over 50 years

NASA announces crew for first trip back to the moon in over 50 years – CBS News

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

-

Artemis moonship returns to Earth with picture-perfect Pacific Ocean splashdown

NASA’s Artemis 1 moonship returned to Earth Sunday, slamming into the upper atmosphere at more than 24,000 mph and enduring a 5,000-degree re-entry inferno before settling to a picture perfect splashdown in the Pacific Ocean to close out a 25-day 1.4-million-mile test flight to the moon and back.

Descending under three huge parachutes, the unpiloted 9-ton Orion capsule gently hit the water 200 miles west of Baja California at 12:40 p.m. EST, 20 minutes after encountering the first traces of the discernible atmosphere 76 miles up.

“I’m overwhelmed. This is an extraordinary day,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “It’s historic, because we are now going back into deep space with a new generation.”

Network TV Pool (above and below)

In an appropriate if unplanned coincidence, the splashdown came 50 years to the day after the final Apollo 17 moon landing in 1972 and just 10 hours after SpaceX launched a Japanese moon lander, the first sent up in a purely a commercial venture, from Cape Canaveral.

“From Tranquility Base to Taurus-Littrow to the tranquil waters of the Pacific, the latest chapter of NASA’s journey to the moon comes to a close. Orion, back on Earth,” said NASA commentator Rob Navias at the moment of Orion’s splashdown, referring to the Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites.

Nelson also reflected on Apollo, saying President John F. Kennedy “stunned everybody with the Apollo generation, and said that we were going to achieve what we thought was impossible.”

“It’s a new day,” Nelson said. “A new day has dawned. And the Artemis generation is taking us there.”

NASA

A joint Navy-NASA recovery team was standing by within sight of the Orion splashdown to inspect the scorched capsule and, after a final round of tests, tow it into the flooded well deck of the USS Portland, an amphibious dock ship.

After the sea water is pumped out, Orion will settle onto a protective cradle for the voyage back to Naval Base San Diego and, eventually, a trip home to the Kennedy Space Center.

Re-entry and splashdown were the final major objectives of the Artemis 1 test flight, giving engineers confidence the spacecraft’s 16.5-foot-wide Apollo-derived Avcoat heat shield and parachutes will work as designed when four astronauts return from the moon after the next Artemis flight in 2024.

Testing the heat shield was, in fact, the top priority of the Artemis 1 mission, “and it is our priority-one objective for a reason,” mission manager Mike Sarafin said Friday.

“There is no arc jet or aerothermal facility here on Earth capable of replicating hypersonic reentry with a heat shield of this size,” he said. “And it is a brand new heat shield design, and it is a safety-critical piece of equipment. It is designed to protect the spacecraft and (future astronauts) … so the heat shield needs to work.”

And it apparently did just that, with no obvious signs of any major damage. Likewise, all three main parachutes deployed normally as did airbags needed to stabilize the capsule in light ocean swells.

NASA

A successful test flight was “what we need in order to prove this vehicle so that we can fly with a crew,” said Deputy Administrator Bob Cabana, a former space shuttle commander. “And that’s the next step, and I can’t wait. … A few minor glitches along the way, but (overall) it performed flawlessly.”

Launched Nov. 16 on the maiden flight of NASA’s huge new Space Launch System rocket, the unpiloted Orion capsule was boosted out of Earth orbit and on to the moon for an exhaustive series of tests, putting its propulsion, navigation, power and computer systems through their paces in the deep space environment.

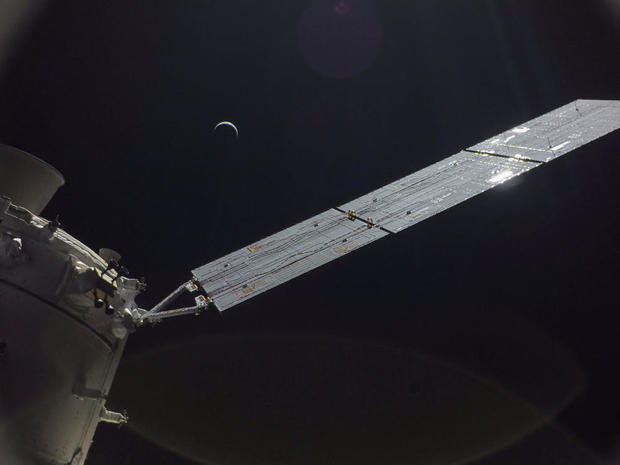

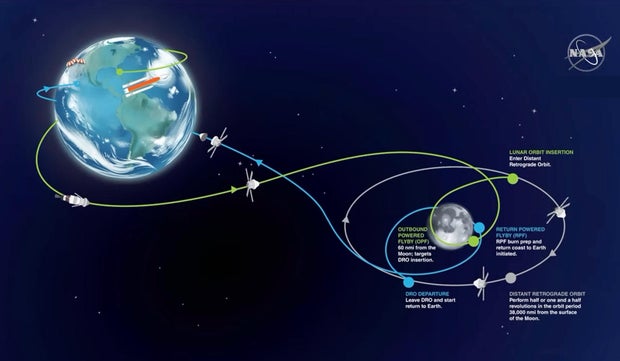

The Orion flew through half of a “distant retrograde orbit” around the moon that carried it farther from Earth — 268,563 miles — than any previous human-rated spacecraft. Two critical firings of its main engine set up a low-altitude lunar flyby last Monday that, in turn, put the craft on course for splashdown Sunday.

NASA originally planned to bring the ship down west of San Diego, but a predicted cold front bringing higher winds and rougher seas prompted mission managers to move the landing site south by about 350 miles, to a point just south of Guadalupe Island some 200 miles west of Baja California.

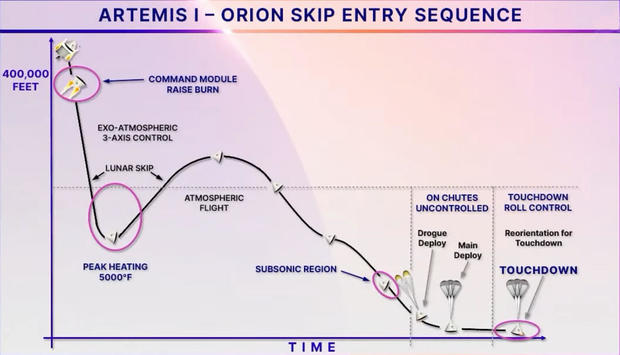

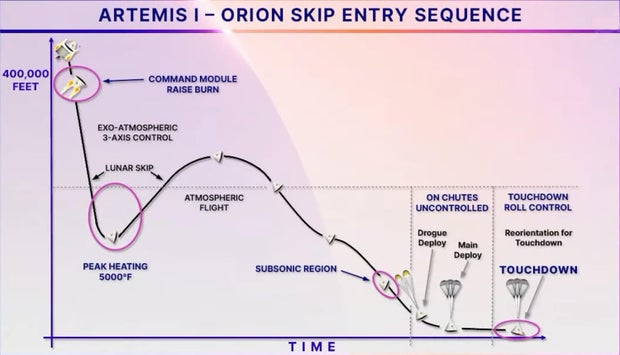

After a final trajectory correction maneuver early Sunday, the Orion spacecraft plunged back into the discernible atmosphere at an altitude of 400,000 feet at 12:20 p.m.

The re-entry profile was designed to ensure that Orion skipped once across the top of the atmosphere like a flat stone skipping across calm water before making its final descent. As expected, Orion plunged from 400,000 feet to an altitude of about 200,000 feet in just two minutes, then climbed back up to about 295,000 feet before resuming its computer-guided fall to Earth.

Within a minute and a half of entry, atmospheric friction began generating temperatures across the heat shield reaching nearly 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit — half the temperature of the sun’s visible surface — enveloping the spacecraft in an electrically charged plasma that blocked communications with flight controllers for about five minutes.

NASA

After another two-and-a-half minute communications blackout during its second drop into the lower atmosphere, the spacecraft continued decelerating as it closed in on the landing site, slowing to around 650 mph, roughly the speed of sound, about 15 minutes after the entry began.

Finally, at an altitude of about 22,000 feet and a velocity of just under 300 mph, small drogue parachutes deployed, pulling off a protective cover along with three pilot chutes. Finally, in a welcome sight to the nearby recovery crew, the capsule’s main parachutes unfurled at an altitude of about 5,000 feet, slowing Orion to a sedate 18 mph or so for splashdown.

Mission duration was 25 days 10 hours 52 minutes.

“It was an incredible mission. We accomplished all of our major mission objectives,” said Michelle Zahner, an Orion mission planning engineer. “The vehicle performed every bit as well as we hoped and even better in a lot of ways.

“This is the farthest any human-rated spacecraft has ever gone, and that required a lot of complex analysis and mission planning. To see it all come together and have such a successful test mission was amazing.”

While flight controllers ran into still-unexplained glitches with its power system, initial “funnies” with its star trackers and degraded performance from a phased array antenna, the Orion spacecraft and its European Space Agency-built service module worked well overall, achieving virtually all of their major objectives.

NASA (both)

If all goes well, NASA plans to follow the Artemis 1 mission by sending four astronauts around the moon in the program’s second flight — Artemis 2 — in 2024. The first moon-landing would follow in the 2025-26 timeframe when NASA says the first woman and the next man will set foot on the lunar surface near the south pole.

While the 2024 flight seems achievable based on the results of the Artemis 1 mission, the Artemis 3 moon landing faces a much more challenging schedule, requiring good performance during the Artemis 3 mission and successful development and testing of the lunar lander NASA is paying SpaceX $2.9 billion to develop.

The lander, a variant of the company’s Starship rocket, has not yet flown to space. But it will require multiple robotic refueling flights in low-Earth orbit before heading to the moon to await rendezvous by astronauts launched aboard an Orion capsule.

SpaceX and NASA have provided few details about the development of the Starship moon lander and it’s not yet known when it will be ready to safely carry astronauts to the moon.

-

Artemis 1 spacecraft heads for Sunday splashdown to wrap up historic mission

Closing out a 25-day voyage around the moon, NASA’s Artemis 1 spacecraft closed in on Earth Saturday, on track for a 25,000-mph re-entry Sunday that will subject the unpiloted capsule to a hellish 5,000-degree inferno before splashdown off Baja California.

In an unexpected but richly-symbolic coincidence, the end of the Artemis 1 mission, expected at 12:39 p.m., will come 50 years to the day after the final Apollo moon landing in 1972.

Testing the Orion capsule’s 16.5-foot-wide Apollo-derived Avcoat heat shield is the top priority of the Artemis 1 mission, “and it is our priority-one objective for a reason,” said mission manager Mike Sarafin.

“There is no arc jet or aerothermal facility here on Earth capable of replicating hypersonic reentry with a heat shield of this size,” he said. “And it is a brand new heat shield design, and it is a safety-critical piece of equipment. It is designed to protect the spacecraft and (future astronauts) … so the heat shield needs to work.”

NASA

Launched November 16 on the maiden flight of NASA’s huge new Space Launch System rocket, the unpiloted Orion capsule was propelled out of Earth orbit and on to the moon for an exhaustive series of tests, putting its propulsion, navigation, power and computer systems through their paces in the deep space environment.