Editor’s Note: Sign up for Unlocking the World, CNN Travel’s weekly newsletter. Get the latest news in aviation, food and drink, where to stay and other travel developments.

CNN

—

It’s the body of water that instils fear and inspires sailors in equal measure. Six hundred miles of open sea, and some of the roughest conditions on the planet – with an equally inhospitable land of snow and ice awaiting you at the end of it.

“The most dreaded bit of ocean on the globe – and rightly so,” Alfred Lansing wrote of explorer Ernest Shackleton’s 1916 voyage across it in a small lifeboat. It is, of course, the Drake Passage, connecting the southern tip of the South American continent with the northernmost point of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Once the preserve of explorers and sea dogs, the Drake is today a daunting challenge for an ever-increasing number of travelers to Antarctica – and not just because it takes up to 48 hours to cross it. For many, being able to boast of surviving the “Drake shake” is part of the attraction of going to the “white continent.”

But what causes those “shakes,” which can see waves topping nearly 50 feet battering the ships? And how do sailors navigate the planet’s wildest waters?

For oceanographers, it turns out, the Drake is a fascinating place because of what’s going on under the surface of those thrashing waters. And for ship captains, it’s a challenge that needs to be approached with a healthy dose of fear.

At around 600 miles wide and up to 6,000 meters (nearly four miles) deep, the Drake is objectively a vast body of water. To us, that is. To the planet as a whole, less so.

The Antarctic Peninsula, where tourists visit, isn’t even Antarctica proper. It’s a thinning peninsula, rotating northwards from the vast continent of Antarctica, and reaching towards the southern tip of South America – the two pointing towards each other, a bit like a tectonic version of Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” in the Sistine Chapel.

That creates a pinch point effect, with the water being squeezed between the two land masses – the ocean is surging through the gap between the continents.

“It’s the only place in the world where those winds can push all around the globe without hitting land – and land tends to dampen storms,” says oceanographer Alexander Brearley, head of open oceans at the British Antarctic Survey.

Winds tend to blow west to east, he says – and the latitudes of 40 to 60 are notorious for strong winds. Hence their nicknames of the “roaring forties,” “furious fifties” and “screaming sixties” (Antarctica officially starts at 60 degrees).

But winds are slowed by landmass – which is why Atlantic storms tend to smash into Ireland and the UK (as they did, causing havoc, with Storm Isha in January buffeting planes to entirely different countries) and then weaken as they continue east to the European continent.

With no land to slow them down at the Drake’s latitude anywhere on the planet, winds can hurtle around the globe, gathering pace – and smashing into ships.

“In the middle of the Drake Passage the winds may have blown over thousands of kilometers to where you are,” says Brearley. “Kinetic energy is converted from wind into waves, and builds up storm waves.” Those can reach up to 15 meters, or 49 feet, he says. Although before you get too alarmed, know that the mean wave height on the Drake is rather less – four to five meters, or 13-16 feet. That’s still double what you’ll find in the Atlantic, by way of comparison.

And it’s not just the winds making the waters rough – the Drake is basically one big surge of water.

“The Southern Ocean is very stormy in general [but] in the Drake you’re really squeezing [the water] between the Antarctic and the southern hemisphere,” he adds. “That intensifies the storms as they come through.” He calls it a “funneling effect.”

Then there’s the speed at which the water is thrashing through. The Drake is part of the most voluminous ocean current in the world, with up to 5,300 million cubic feet flowing per second. Squeezed into the narrow passage, the current increases, traveling west to east. Brearley says that at surface level, that current is less perceptible – just a couple of knots – so you won’t really sense it onboard. “But it does mean you’ll travel a bit more slowly,” he says.

For oceanographers, he says, the Drake is “a fascinating place.”

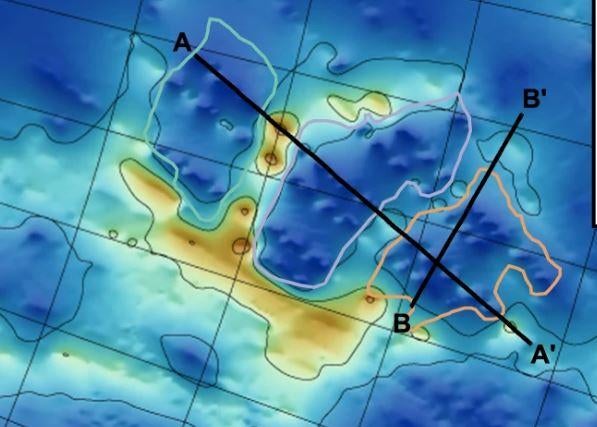

It’s home to what he calls “underwater mountains” below the surface – and the enormous current squeezing through the (relatively) narrow passage causes waves to break against them underwater. These “internal waves,” as he calls them, create vortices which bring colder water from the depths of the ocean higher up – important for the planet’s climate.

“It’s not just turbulent at the surface, though obviously that’s what you feel the most – but it’s actually turbulent all the way through the water column,” says Brearley, who regularly crosses the Drake on a research ship. Does he get scared? “I don’t think I’ve ever been really fearful, but it can be very unpleasant in terms of how rough it is,” he says candidly.

One other key thing that makes the Drake so scary: our fear of the Drake itself.

Brearley points out that until the Panama Canal opened in 1914, ships going from Europe to the west coast of the Americas had to dip round Cape Horn – the southern tip of South America – and then trundle up the Pacific coast.

“Let’s say you were shipping goods from western Europe to California. You either had to offload them in New York and do the journey across the US, or you had to go all the way around,” he says. It wasn’t just large cargo ships, either; passenger ships made the same route.

There’s even a monument at the tip of Cape Horn, in memorial of the more than 10,000 sailors who are believed to have died traveling through.

“The routes between the south of South Africa and Australia, or Australia or New Zealand to Antarctica, don’t really lie on any major shipping routes,” says Brearley. “The reason it’s been so feared over the centuries is because the Drake is where ships really have to go. Other parts [of the Southern Ocean] can be avoided.”

Navigating the Drake is an extremely complex task that demands humility and a side of fear, says Captain Stanislas Devorsine, one of three captains of Le Commandant Charcot, a polar vessel of adventure cruise company Ponant.

“You have to have a healthy fear,” he says of the Drake. “It’s something that keeps you focused, alert, sensitive to the ship and the weather. You need to be aware that it can be dangerous – that it’s never routine.”

Devorsine made his Drake debut as a captain over 20 years ago, sailing an icebreaker full of scientists over to Antarctica for a research stint.

“We had very, very rough seas – more than 20 meter [66 feet] swells,” he says. “It was very windy, very rough.” Not that Ponant’s clients face anything like that. Devorsine is quick to point out that the comfort levels for a research ship – and the conditions it will sail in – are very different from those for a cruise.

“We are extremely cautious – the ocean is stronger than us,” he says. “We’re not able to go in terrible weather. We go in rough seas but always with a big safety margin. We’re not gambling.”

Even with that extra safety margin, though, he admits that crossing the Drake can be a hairy experience. “It can be very rough and very dangerous, so we take special care,” he says.

“We have to choose the best time to cross the Drake. We have to adapt our course – sometimes we don’t head in our final direction, we alter the course to have a better angle with the waves. We might slow down to leave a low pressure path ahead, or speed up to pass one before it arrives.”

The ‘Drake shake’ and broken plates

Of course, every time you get on a ship – whether it’s a simple ferry ride or a fancy cruise – the crew will already have meticulously planned the journey, checking everything from the weather to the tides and currents. But planning for a crossing of the Drake is on a whole new level.

Weather forecasting has improved in the two decades since Devorsine’s first ride, he says – and these days crew start planning the voyage while passengers are making their way to South America from all over the globe.

Sometimes they leave late; sometimes they head back early, to beat bad weather. Devorsine – who makes the return journey about six to eight times per year – estimates that the unusually calm “Drake lake” effect happens once in every 10 crossings, with particularly rough conditions (that “Drake shake”) once or twice in every 10 journeys.

Of course, he knows what’s in store long before the passengers reach the ship.

“We look ahead to have the best option to cross. Normally I look at the weather 10 days or a week before, just to have an idea of what it could be,” he says.

“Then I check the forecast once per day, then two or three days before departure I start looking at it twice per day. If it’s going to be a challenging passage you look every six hours. If you have to adjust your departure time, then you look at it very closely to be very accurate.”

His safety margin means that he’s calculating a route that will get you across not just alive, but also as comfortably as possible. Hearing an anecdote about broken crockery and furniture on another operator, he sighs, “That’s a bit too far for me.”

“Before you have any issue with a storm, you have to keep a comfortable ship,” he says. The safety margin is to be sure that the guests will enjoy being in Antarctica, and that we won’t turn around because we have a problem… like injured people.”

In extreme conditions, he orders extra weather advice from Ponant HQ, but if you’re imagining the staff on the bridge desperately radioing for advice as waves batter the ship, think again.

“It would never happen to be in the middle of the Drake with bad conditions, needing assistance from headquarters because it would mean we didn’t have any safety margin before departure. When we cross and it’s going to be challenging, we have a big safety margin and the ship is not at all in danger.”

They are in contact with headquarters with high level satellite antennae throughout the crossing, with both satellite and radio backup if needed – Devorsine says he can’t imagine ever losing contact, whatever the weather.

Devorsine, who now spends 90% of his time sailing in polar waters, feels at home on the Drake. “When I was a little child, I read books about the maritime adventures of sailors and polar heroes,” he says. “I was attracted by tough things – I like challenges. This is why I followed the path to be able to sail in these areas.”

His first experience of the area was doing a “race around the world” in a sailboat as a youngster, heading south from his native France and rounding Cape Horn.

“It was my dream because it’s difficult, dangerous and challenging,” he says.

He’s not the only one. Some guests are drawn to Antarctica trips because of the tough journey. “I guess [they] are attracted by these areas [of the Southern Ocean] because it’s wild, it can be rough, and it’s a unique experience to go there,” he says.

Not everone’s a thrill-seeker though. As managing director of Mundy Adventures, an adventure travel agency, Edwina Lonsdale is dealing with a clientele already used to discomfort – yet she says crossing the Drake is a “conversation topic” during booking.

“it’s something we would raise to make sure people are completely aware of what they’re buying,” she says. “[Going to Antarctica] is a huge investment – you need to talk through every aspect and make sure nothing’s an absolute no.”

Lonsdale advises that passengers nervous of feeling sick should choose their ship carefully. In the past, vessels heading to Antarctica tended to be uncomfortable metal boxes built to take a heavy beating. But in recent years, companies have introduced more technically advanced vessels: like Le Commandant Charcot, which was the world’s first passenger vessel with a Polar Class 2 hull – meaning it can go deeper and further into the ice in polar regions – when it debuted in 2021.

Two of Aurora Expeditions’ ships, the Greg Mortimer and Sylvia Earle, use a patented inverted bow, designed to slide gently through the waves, reducing impact and vibration and improving stability, rather than “punching” through the water as a regular bow shape does, which makes the bow rock up and down.

Lonsdale says that the fancier the vessel and the offerings onboard, the more distractions you’ll have if bad weather hits. Newer boats often have more spacious rooms and bigger windows so that you can watch the horizon, which helps to lessen seasickness. If the budget allows, she says, book a suite – you won’t just get more space, you’ll (likely) have floor-to-ceiling windows, too.

But a word of advice – she recommends a careful selection not just of the right operator for you, but of the ship itself.

“Just because a company has a fleet with a very modern ship doesn’t mean the whole fleet will be like that,” she says.

So you’ve conquered your fears, booked your ticket and you’re about to set sail. Bad news: the captain is predicting the Drake shake. What to do?

Hopefully you’ve come prepared. Most ships have ginger candies on offer during bad weather, but bring your own, as well as any anti-seasickness medication you want to take. Some passengers swear by acupressure “seeds”: tiny spikes, attached to your ears with a sticking plaster, designed to stimulate acupuncture points. Some ships offer acupuncture onboard; alternatively you can get it done beforehand, since the seeds last for some time.

Devorsine’s top tips are to keep your eyes on the horizon, hold onto the handrail when walking around, be careful around doors, and “don’t jump out of bed.”

Jamie Lafferty, a photographer who leads excursions on Antarctic cruises, says that of his 30-odd crossings, “I’ve had one where it felt like I was going to fall out of bed and that was the second time, way back in 2010 when there was a lot more guesswork involved. Crossing the Drake Passage is much, much more benign than it used to be thanks to the accuracy of modern forecasting models and stabilizers on more modern cruise ships. This doesn’t mean it’ll be smooth, but it’s vastly less chaotic and unpredictable than it used to be.”

His top tip? “Take seasickness medication before heading out into open sea – once you start spewing, tablets aren’t going to be any use.”

Warren Cairns, senior researcher at the Institute of Polar Sciences of the National Research Council of Italy, has a bit of extra help.

“The only thing that works for me is going to the ship’s medic for a scopolamine patch,” he says. “It’s so rough, normal seasickness pills are just to get me to the infirmary.” Although he has it worse than the average tourist – on trips to Antarctica, their research ships have to pause for house to take samples. “The waves come from all sorts of directions as the thrusters keep it in place,” he says. “When you’re underway it’s a much more regular motion.”

Lonsdale says it’s important not to fight it if you feel ill: “Just go to bed.” But equally, she says, don’t expect it: “It may be calm. You may not feel ill.”

People suffer differently from seasickness she says. “The Pacific has very long, slow swells, Channel crossings [between the UK and France] have quite a bouncy experience. Lots of people say crossing the Drake in very rough weather is uneven enough to not make them ill at all.” On that plate-smashing crossing, for example, this reporter – who was watching 40-foot waves from the observation deck – never got sick.

Remember that however it feels, you’re safe. “There’s an extraordinary level of safety in the build of those ships doing this,” says Lonsdale. Add in the safety margins that the likes of Devorsine build in, and you’re in uncomfortable, but not dangerous, territory.

And if all else fails, remember why you’re there.

“The motivation and excitement to discover those latitudes is very important to fight the seasickness,” says Devorsine. Lonsdale agrees.

“If you were going to the moon, you’d expect the journey to be uncomfortable but it’d be worth it,” she says. “You just have to think, ‘This is what I need to get from one world to another.’”