What can reishi mushrooms, shiitake mushroom extracts, and whole, powdered white mushrooms do for cancer patients?

“A regular intake of mushrooms can make us healthier, fitter, and happier, and help us live longer,” but what is the evidence for all that? “Mushrooms are widely cited for their medicinal qualities, yet very few human intervention studies have been done using contemporary guidelines.”

There is a compound called lentinan, extracted from shiitake mushrooms. To get about an ounce, you have to distill around 400 pounds of shiitakes, about 2,000 cups of mushrooms. Researchers injected the compound into cancer patients to see what happens. The pooled response from a dozen small clinical trials found that the objective response rate was significantly improved when lentinan was added to chemotherapy regimens for lung cancer. “Objective response rate” means, for example, tumor shrinkage, but what we really care about is survival and quality of life. Does it actually make cancer patients live any longer or any better? Well, those in the lentinan group suffered less chemo-related toxicity to their gut and bone marrow, so that alone might be reason enough to use it. But what about improving survival?

I was excited to see that lentinan may significantly improve survival rates for a type of leukemia. Indeed, researchers found that adding lentinan to the standards of care increased average survival, reduced cachexia (cancer-associated muscle wasting), and improved cage-side health. Wait, what? This was improved survival for brown Norwegian rats, so that the so-called clinical benefit only applies if you’re a rat or a veterinarian.

A compilation of 17 actual human clinical studies did find improvements in one-year survival in advanced cancer patients but no significant difference in the likelihood of living out to two years. Even the compilations of studies that purport that lentinan offers a significant advantage in terms of survival are just talking about statistical significance. As you can see below and at 2:15 in my video White Button Mushrooms for Prostate Cancer, it’s hard to even tell these survival curves apart.

Lentinan improved survival by an average of 25 days. Now, 25 days is 25 days, but we “should evaluate assertions made by companies about the miraculous properties of medicinal mushrooms very critically.”

Lentinan has to be injected intravenously. What about mushroom extract supplements you can just take yourself? Researchers have noted that shiitake mushroom extract is available online for the treatment of prostate cancer for approximately $300 a month, so it’s got to be good, right? Men who regularly eat mushrooms do seem to be at lower risk for getting prostate cancer—and apparently not just because they eat less meat or consume more fruits and vegetables in general. So, why not give a shiitake mushroom extract a try? Because it doesn’t work. On its own, it is “ineffective in the treatment of clinical prostate cancer.” Researchers wrote that “the results demonstrate that claims for CAM [complementary and alternative medicine], particularly for herbal and food supplement remedies, can be easily and quickly tested.” Put something to the test? What a concept! Maybe it should be required before individuals spend large amounts of money on unproven treatments, or, in this case, a disproven treatment.

What about God’s mushroom (also known as the mushroom of life) or reishi mushrooms? “Conclusions: No significant anticancer effects were observed”—not even a single partial response. Are we overthinking it? Plain white button mushroom extracts can kill off prostate cancer cells, at least in a petri dish, but so could the fancy God’s mushroom, but that didn’t end up working in people. You don’t know if plain white button mushrooms work on real people until you put them to the test.

What I like about this study is that the researchers didn’t use a proprietary extract. They just used regular whole mushrooms, dried and powdered, the equivalent of a half cup to a cup and a half of fresh white button mushrooms a day, in other words, a totally doable amount. The researchers gave them to men with “biochemically recurrent prostate cancer”—the men had already gotten a prostatectomy or radiation in an attempt to cut or burn out all the cancer, but it returned and started growing, as evidenced by a rise in PSA levels, an indicator of prostate cancer progression.

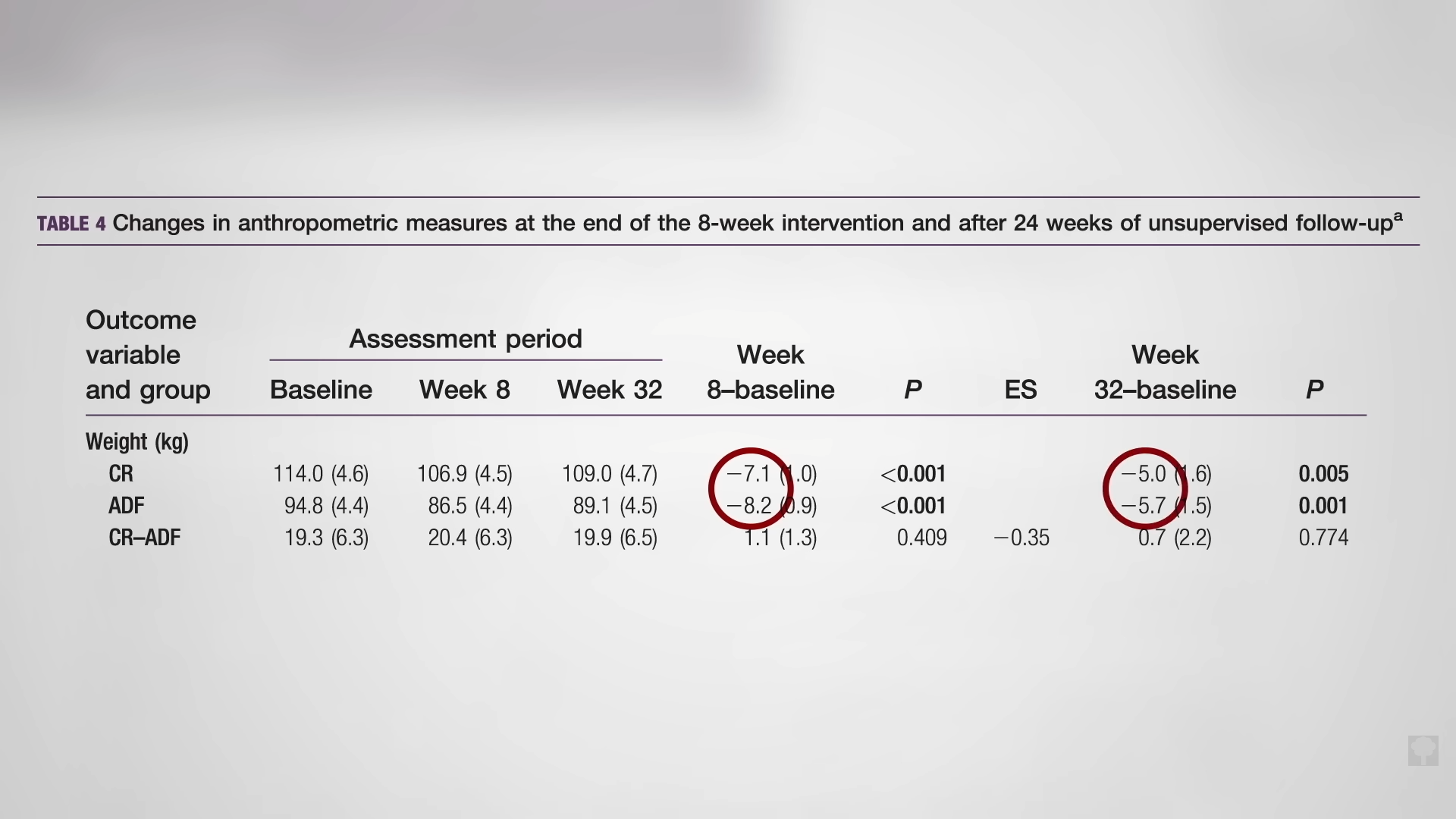

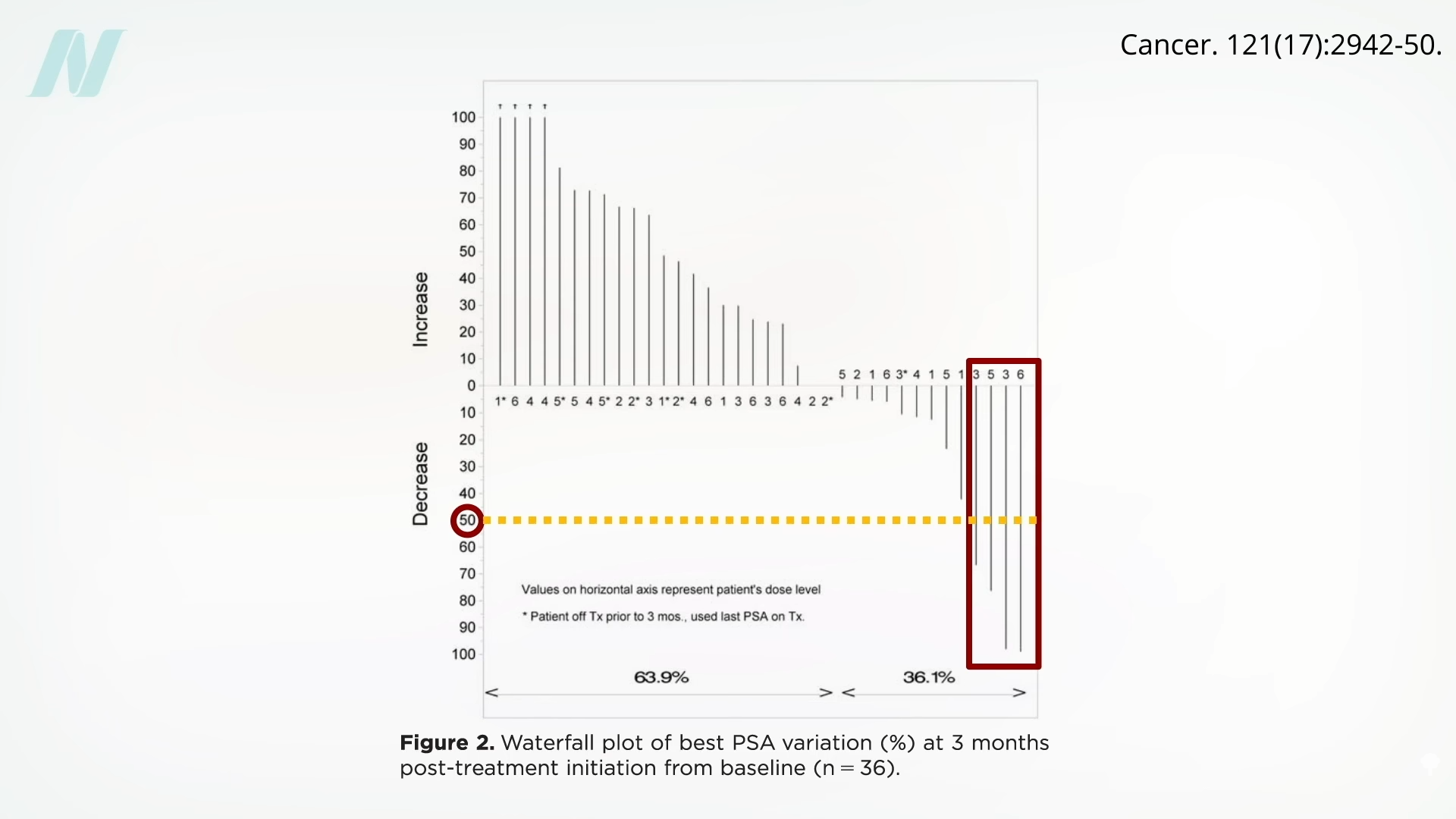

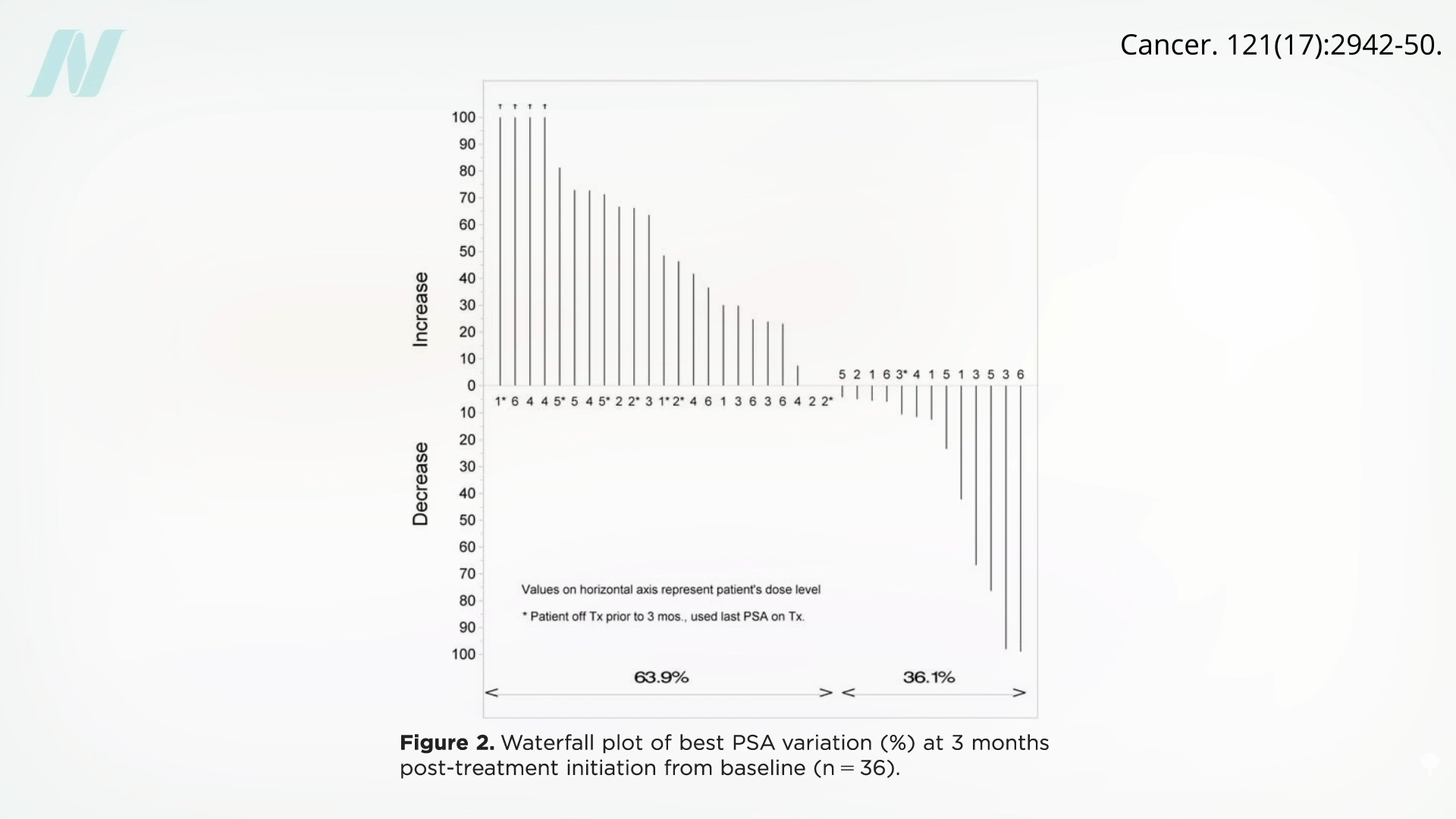

Of the 26 patients who had gotten the button mushroom powder, 4 appeared to respond, meaning they got a drop in PSA levels by more than 50% after starting the mushrooms, as you can see here and at 4:31 in my video.

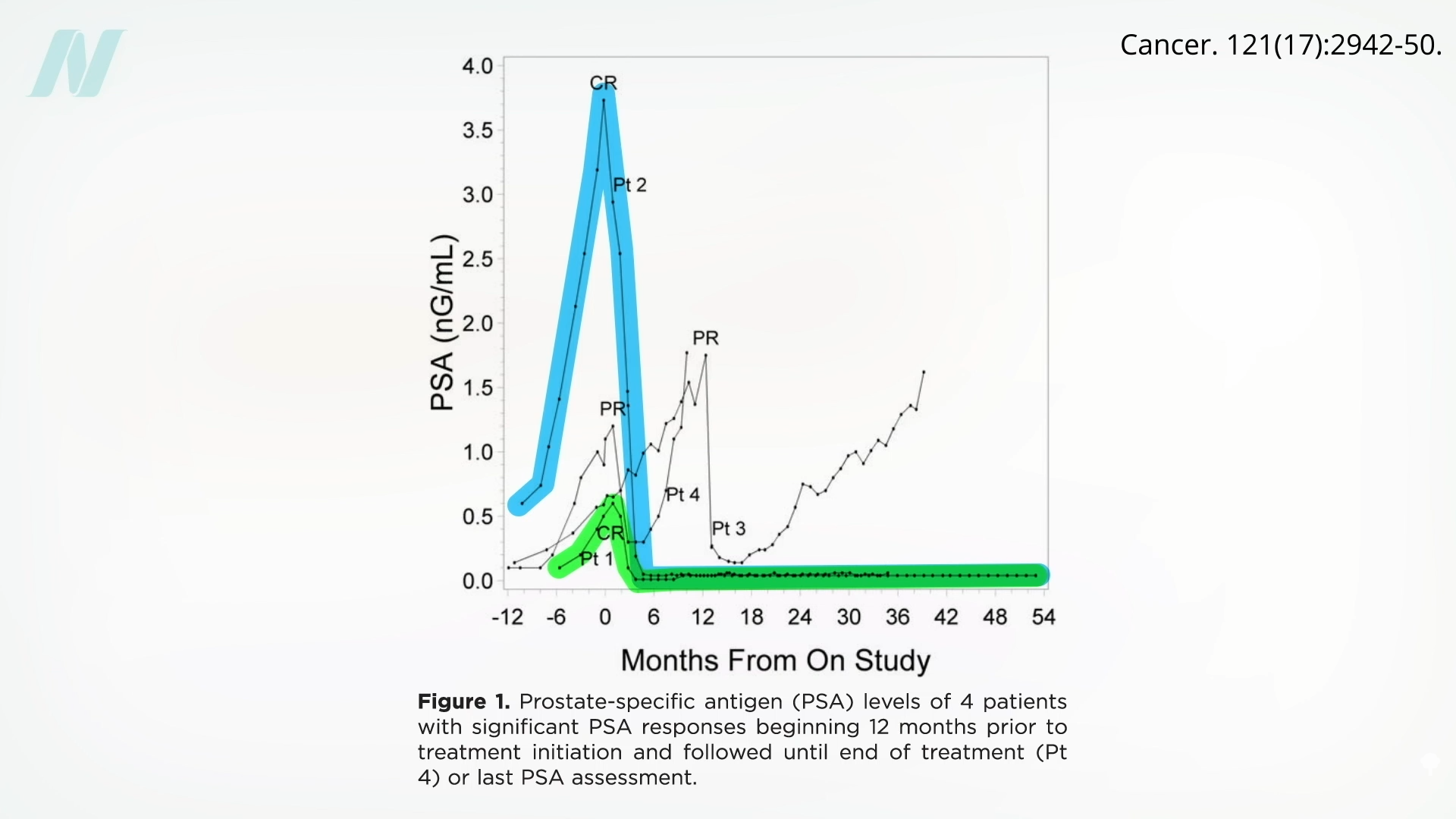

In the next graphic, below and at 4:22, you can see where the four men who responded started out in the months leading up to starting the mushrooms. Patient 2 (“Pt 2”) was my favorite. He had an exponential increase in PSA levels for a year, then he started some plain white mushrooms, and boom! His PSA level dropped to zero and stayed down. A similar response was seen with Patient 1. Patient 4 had a partial response, before his cancer took off again, and Patient 3 appeared to have a delayed partial response.

Now, in the majority of cases, PSA levels continued to rise, not dipping at all. But even if there is only a 1-in-18 chance you’ll be like Patients 1 and 2, seen below and at 5:12, you may get a prolonged, complete response that continues.

We aren’t talking about weighing the risks of some toxic chemotherapy for the small chance of benefit, but just eating some inexpensive, easy, tasty plain white mushrooms every day. Yes, the study didn’t have a control group, so it may have just been a coincidence, but rising PSAs in post-prostatectomy patients are almost always indicators of cancer progression. And, what’s the downside of adding white button mushrooms to your diet?

In these two patients, their PSA levels became undetectable, suggesting that the cancer disappeared altogether. They had already gone through surgery, had gotten their primary tumor removed, along with their entire prostate, and had already gone through radiation to try to clean up any cancer that remained, and yet the cancer appeared to be surging back—until, that is, they started a little plain mushroom powder.

Doctor’s Note

If you missed the previous blog, check out Medicinal Mushrooms for Cancer Survival.

Also check out Friday Favorites: Mushrooms for Prostate Cancer and Cancer Survival.

For more on mushrooms, see Breast Cancer vs. Mushrooms and Is It Safe to Eat Raw Mushrooms?.

For more videos on prostate cancer, check the related posts below.

Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

Source link

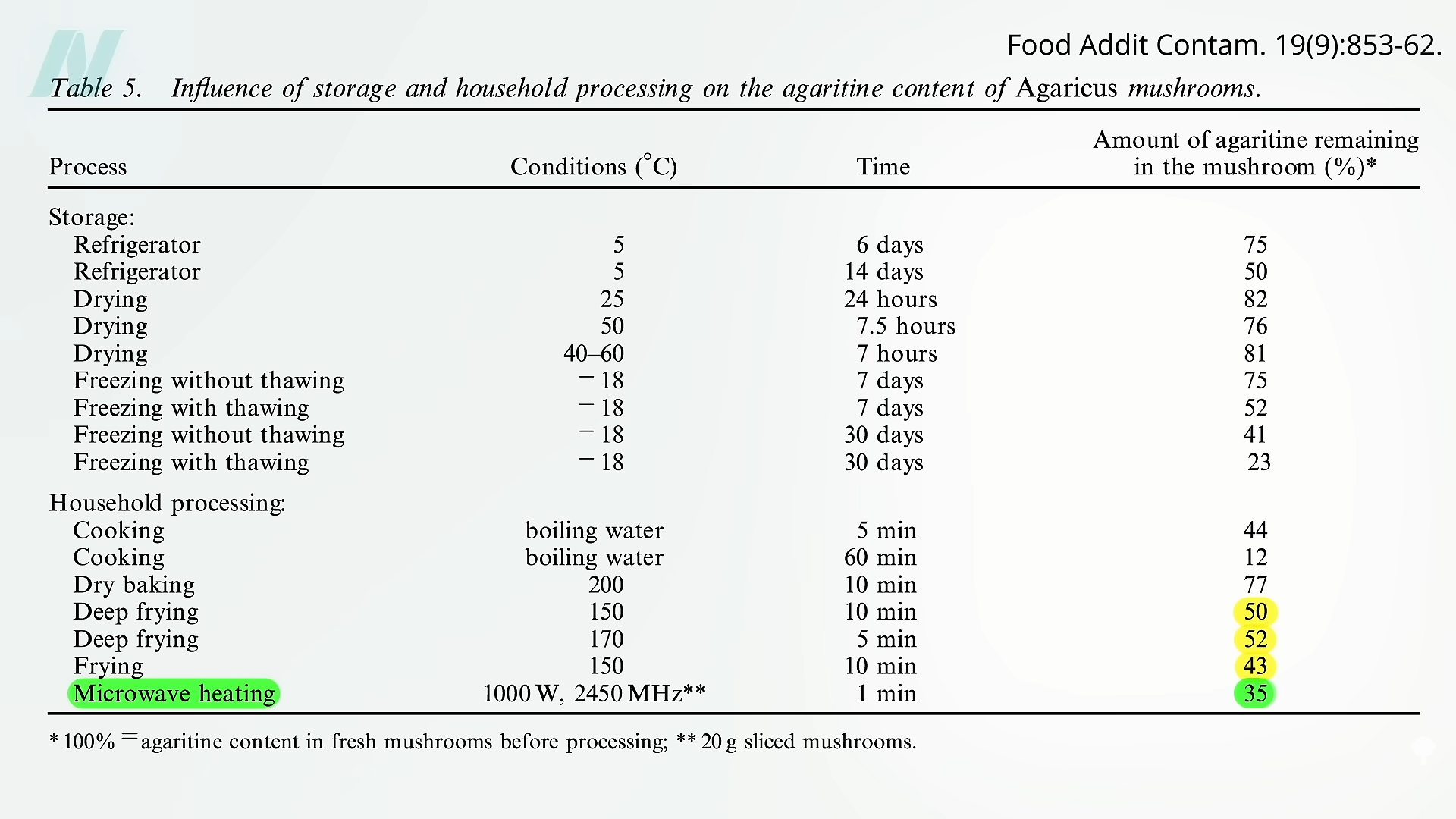

My technique is to add dried mushrooms into the pasta water when I’m making spaghetti. Between the reductions of 20 percent or so from the drying and 60 percent or so from boiling for ten minutes and straining, more than 90 percent of agaritine is eliminated.

My technique is to add dried mushrooms into the pasta water when I’m making spaghetti. Between the reductions of 20 percent or so from the drying and 60 percent or so from boiling for ten minutes and straining, more than 90 percent of agaritine is eliminated. But, again, this is all

But, again, this is all