[ad_1]

Maddy Montiel and Brad Butterfield marveled at the community they found this semester at Cal Poly Humboldt.

Montiel, an environmental science major, and Butterfield, a journalism major, had lived in their vehicles for several years, the only way, they said, that they could afford to attend college. They usually found parking in campus lots or on nearby streets.

But the pair and about 15 others like them — students living in sedans, aging campers, a converted bus, who could afford a $315 annual parking permit but not rent — found one another on campus parking lot G11. They started parking together in a row of spaces and named their community “the line.” They shared resources: propane tanks to heat their living quarters, ovens to cook meals. They helped one another seal leaky roofs and formed an official campus club aiming to secure a mailing address.

They felt safe.

Students Brad Butterfield and Maddie Montiel embrace next to a pair of parking tickets she received from Cal Poly Humboldt police.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

“None of us have ever had something like that before,” said Montiel, 27. “People who live like this don’t really congregate, and try to stay out of view.”

Then the notices arrived late last month. The university was going to enforce a campus policy, written into parking regulations, that prohibits overnight camping. Remove vehicles by noon on Nov. 12, or they could be towed and students could face disciplinary action, the letter said.

Montiel and Butterfield moved their vehicles to another campus parking lot, hoping the university would back down if they became less visible. They found two spots under redwood trees at the edge of campus. Others from G11 scattered, driven back into hiding.

On the morning of Nov. 13, several students who stayed at G11 and other campus lots awoke to discover parking violations on their windshields, a $53 fine for living overnight in their vehicles, $40 for those whose vehicles were too large for one spot.

The actions by Humboldt — defended by university officials as necessary for health and safety — provide an up-close look at how low-income California State University students determined to earn a college degree struggle to meet their basic needs amid the state’s student affordable housing crisis.

Cal Poly Humbolt student Caleb Chen eats noodles in his van in campus parking lot G11.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

“We’re putting everything we have into our education in order to be here,” Montiel said. “For them to just keep putting all of this added pressure onto us just seems really unnecessarily cruel.”

The campus-wide email landed at the end of October: The university would soon prohibit students from sleeping in cars.

“Overnight camping in University parking lots creates unsanitary and unsafe conditions for both those encamped and for our campus community at large,” the email said. “The University Police Department and other campus offices have taken calls from concerned members of the campus community expressing fear and frustration about the situation.”

Days later, three administrators visited students parked in G11 to share details about the enforcement, said Butterfield, 26.

“This is a direct response to the public health and safety concerns that have stemmed from overnight activity in University parking lots,” said a letter given to students. The university would provide temporary emergency housing to students through the end of the semester, which ends in December, or would help students identify campsites or other locations where they could park off campus.

Tom Jackson, Cal Poly Humboldt’s president, declined an interview request through spokesperson Aileen Yoo, who said university staff is also available to help students find longer-term housing solutions.

“These aren’t evictions. The University is enforcing a long-standing parking policy,” Yoo said in an email.

Two people walk through the lobby of a building at Cal Poly Humboldt.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

In response, faculty in the sociology department wrote a letter to university officials, condemning them for upholding a policy that “criminalizes” the students. The message to the campus community “framed our houseless students as a group of people who are feared, clearly intimidating them to get them off campus,” the letter said.

“There are ways that we can address this in a way that best serves our students and community,” said Tony Silvaggio, chair of the sociology department and vice president of the Humboldt chapter of the California Faculty Assn. “And it’s not just kicking them off campus to live on the streets somewhere else.”

The University Senate, a campus governing body, passed a resolution urging the university to suspend its enforcement of the parking policy until the end of the academic year, include students in decision-making and explore “safe parking” options on campus.

The students of G11 started an online petition, pushing back against the characterization that they are unsanitary or create danger. The students said they went out of their way to pick up trash and to maintain a clean environment.

The campus-wide email was “an attempt to shame, humiliate, and isolate the houseless community on campus,” the petition said. “We are living in our vehicles and are legally homeless because, quite simply, we cannot afford rent.”

After the uproar, the university sent a second campus-wide email that said, “The challenges of affordable housing can be particularly acute for students, and the University is invested in supporting them.” But the university did not reverse its decision.

Butterfield and Montiel raced to persuade officials to reconsider, meeting with administrators, including campus police and the dean of students.

They tried to schedule a meeting with Mark Johnson, the university’s chief of staff, and Cris Koczera, director of risk management and safety services. But an email from a campus ombudsman told the students the administrators would not meet with them. The university’s decision and the options it presented were clear, the email said, and “no constructive discussion is to be had.”

For Montiel, Humboldt was a world away from San Bernardino, her hometown. She first visited the university in high school, tagging along on a road trip with a friend.

Students Brad Butterfield and Maddy Montiel, along with their dog Ollie, prepare for class after taking a shower on the campus of Cal Poly Humboldt.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Montiel was struck by the abundance of the nearby forest, the beauty of the redwoods that towered over campus. Years later, she learned the college had an environmental science program that offered experiences that aligned with her goals of working in ecological restoration.

“I fell in love with the place and always saw it as a dream — but never attainable because it was so far, and it’d be too expensive,” she said.

She attended Riverside City College for five years, enrolling in classes full time as she juggled multiple jobs. After she earned multiple associate degrees, she told herself, “I’m just going to go for it and figure out living up in Humboldt.”

She is making it work by living in a 1995 Chevy Coachman, purchased with a loan that costs her $600 a month. She has also taken out $25,000 in student loans for tuition and fees and works as a studio tech in the campus metalsmithing studio to pay for other living expenses.

In fall 2022, Montiel purchased a campus parking permit that allows students to park on campus during the academic year and eventually settled into the G11 lot.

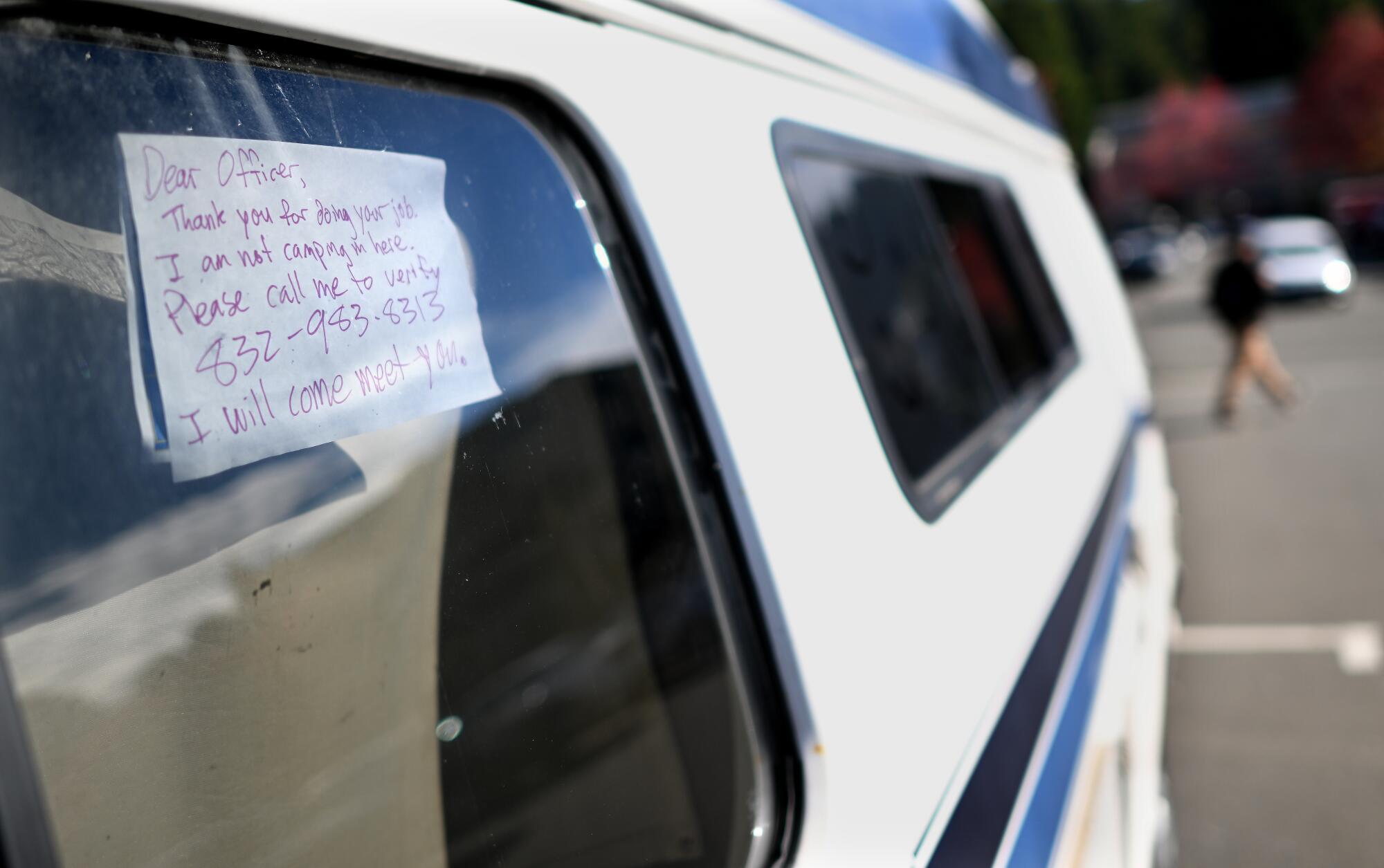

A student’s note on the window of his van tells police he is not camping at Cal Poly Humboldt. The university recently told students they could not sleep in their cars overnight.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

In her aging Coachman, she studies on a tray table and practices yoga on a narrow strip of walkway. She cooks meals on a small propane stove inside. Her bed is lofted over the driver and passenger seats. Every other week, she visits a dump station to empty waste and fill her water tanks.

Over time, more students began to park in G11, a lot situated among dorms and a short walk from a campus market. The location was convenient for shuttling back and forth between classes or to access the campus gym for showers. This semester, the 15 to 20 students found comfort in their community. They celebrated the start of the year with a beach bonfire and eventually formed the Alternative Living Club.

Student Caleb Chen searches for water late at night with a gallon container on the campus of Cal Poly Humboldt.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

The club began as a way for unhoused students to receive mail, as they needed an address for scholarship and job applications. Montiel, the club’s president, envisioned more. The club could offer a support system for unhoused students, an avenue to propose ideas about how the university could better help them. They talked about pooling funds for a storage facility, formalizing a safe parking program.

Montiel said many cash-strapped students have approached club members and said they are leaning toward moving into vehicles “because it’s their last and only option” to stay in college.

But now Montiel wonders if the club and the growing visibility of homelessness on campus led to the university’s decision to displace them.

“We’re kind of more seen,” she said. “We weren’t just scattered and hidden.”

Carrie White, another student who took up residence in the parking lot, transferred to Humboldt after graduating from community college in Utah. As she calculated her living expenses, the 27-year-old biology major realized she could not afford rent while attending school.

“I can’t afford to pay $1,500, $900 a month and work and then do a STEM degree,” said White, who is from England. “I can’t afford it.”

Student Brad Butterfield prepares to move his camper off the Cal Poly Humboldt campus.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

So she purchased an old school bus and gradually converted it to her home. At Humboldt, she works up to 20 hours a week, balancing a research assistant job with an internship in 3D facial reconstruction and a fellowship where she volunteers in the community.

As a person who is autistic, White said, she relies on routine and is sensitive to noise and light. Living in her bus, she has some control over her environment.

“I’ve tried to do those things with my budget and with my situation, and then this has happened,” she said. “There’s a lack of thought and consideration.”

This isn’t the first time in recent years that Cal Poly Humboldt has generated anger over its response to student housing shortages.

Last academic year — in anticipation of a large enrollment jump after becoming a polytechnic campus — the university announced it would prioritize limited on-campus housing for first-year students. Many continuing students would have to search for housing in off-campus rentals or at a limited number of motels leased by the university.

Around the same time, officials also weighed a proposal to house students on a floating barge, an idea that attracted national media attention and was mocked in a brief segment by Stephen Colbert. The barge plan has not materialized, and enrollment remained flat this academic year.

Brad Butterfield stores his belongings with his dog Ollie after taking a shower on the campus of Cal Poly Humboldt.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

But the university’s approach to dealing with housing shortages points to a larger issue in the California State University — the nation’s largest four-year public higher education system, with nearly 460,000 students.

“One in 10 Cal State students experience homelessness,” according to research published in 2016. Another report, published by the Cal State system last year, found nearly 33,000 students lack housing assistance they need.

At Cal Poly Humboldt, 2,069 beds were available on campus in 2022, the report said. The campus enrolled nearly 6,000 students.

Humboldt also faces challenges unique to its location as the northernmost Cal State campus. Arcata, a city of about 19,000 people where Cal Poly Humboldt is located, is in the midst of its own housing crisis. Earlier this month, the City Council declared a shelter crisis.

The declaration enabled the city to draw on funding to continue operating a safe parking program, which is operated by Arcata House Partnership, an organization that provides support for unhoused people. The program provides a space for residents who live in their cars to safely park and services including charging stations, bathrooms and meals, as they work to find stable housing.

But the program is full, and up to 20 people at a time are on the waitlist, said Darlene Spoor, executive director of Arcata House Partnership. She said she would be “willing to have a conversation with people from the university about whether we could open a safe parking program for students.”

Students Derek Beatty, left, and Caleb Chen hang out late at night in parking lot G11 at Cal Poly Humboldt.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, Spoor said, more people have moved to Humboldt and purchased homes at high prices, pricing some longtime residents out of homebuying and driving up rental costs.

Plans are underway to ease the strain on students. By fall 2025, Cal Poly Humboldt plans to build more on-campus dorms and apartments, increasing the number of available beds by 1,250.

But on-campus options still remain out of reach for some students. A dorm room shared by three people and a required basic meal plan, for example, is expected to cost at least $10,900 per student next academic year. Room and board in a double costs about $13,000; a plan for a single dorm room runs more than $14,500 for the nine-month academic year.

Neither of those options would have worked for Steven Childs. The 47-year-old wildlife major said he would not have attended Humboldt if he could not live out of his cargo van.

He was scrolling YouTube one day when he came across a video that showed Humboldt students living in their cars. He thought to himself, “Oh, man, I think that’s my option. That’s the only way that seems reasonable.”

Childs, who lives in the San Gabriel Valley when school is not in session, gave up work as a private investigator to attend Humboldt. His wife’s salary now supports them both.

“I’m pushing 50, and I don’t want to be saddled with college debt through retirement,” he said. “I could sacrifice and live out of a vehicle.”

Butterfield, the journalism major, could not find housing that worked within his budget range of $650 to $900 a month, plus security deposit and other fees.

He decided to pay for his education with savings from service-industry and other jobs, and does not want student loans.

Brad Butterfield and Maddy Montiel study in a camper parked on the Cal Poly Humboldt campus.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

He lives in an 1976 GMC Sportscoach that cost $9,500. He spends at least $200 a month on expenses for the RV, including insurance and propane.

“I had a couple hundred dollars left in my bank account to come up here and try to live off of,” he said.

On the night of Nov. 13 — hours after receiving citations for overnight camping — about 10 G11 students gathered inside a small university building. They worried they could face disciplinary action or lose their vehicles. Five unpaid tickets could get them towed.

One student said he had struggled to fall asleep the night before, worried that parking enforcement would ticket him. Another student wondered aloud about what they would do next semester. They brainstormed ways to draw more attention to their fight.

They talked about occupying a building. They discussed how they would appeal the parking violations, and weighed potential legal action. Two students said they planned to sleep overnight in a campus study room so footage from security cameras could prove they did not sleep in their vehicles.

In the end, they agreed to stay in touch over a group chat to prepare for the upcoming weeklong fall break.

Student Brad Butterfield outside his camper at the Cal Poly Humboldt campus.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Montiel and Butterfield had decided to move their vehicles again, this time off campus, to a city street next to a university parking lot. They have to move the vehicles by 7 a.m, when the city begins enforcing metered parking restrictions.

“Love you guys,” Montiel told the group before everyone went their separate ways.

[ad_2]

Debbie Truong

Source link