When Vladimir Putin ordered his armies into Ukraine on February 24, 2022, it was not to preempt Kyiv’s then-distant prospects of NATO accession, nor, primarily, to take his place in history alongside Peter the Great.

It was to avoid the fate of Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko.

Both Putin and Lukashenko came to power after winning one more-or-less free-and-fair election, then both immediately set to work making sure that no one else could do the same. Despite Putin’s nuclear arsenal, his Siberian gas, his veto in the U.N. Security Council, his capacity to project air power as far afield as Syria, and his cult-figure status among fringe members of the international right and left alike, the methods that the Russian and Belarusian presidents-for-life rely on for maintaining power at home are nearly identical.

In August 2020, after 26 years of dictatorial rule, Belarusians finally turned against their corrupt, Soviet-nostalgic, aging autocrat. Putin, who was appointed acting president of the Russian Federation on New Year’s Eve, 1999, was desperate to prevent the Russian people from souring on their own autocrat in a similar way.

Sasha Mordovetz/GETTY IMAGES

Plummeting Popularity Brings Desperation for ‘Big Win’

In 2012, when Putin returned to the Kremlin’s top spot following a four-year stint as Prime Minister to placeholder commander-in-chief Dmitry Medvedev, the man in control of the world’s second-largest nuclear arsenal had a problem. Although he had claimed an official 64.35% of that year’s vote against a handpicked field of symbolic opposition candidates, most of his constituents were already preparing for life in a Russia without Putin.

In October of that year, seven months after Putin’s third election victory, the independent polling agency Levada Center began asking Russians if they would like to see their increasingly eternal head of state stay on as president past 2024, when his second pair of consecutive terms in office would come to an end.

Although his personal approval rating stood at 67%, only 34% of those surveyed hoped to see Putin ultimately serve a fifth term in the Kremlin. When the “2024” question was posed again in October 2013, the “yes” figure had slipped further, down to 33%.

Then Crimea changed everything.

In late February 2014, following the popular revolution which saw Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich flee Kyiv for refuge in Russia, Russian special forces soldiers dressed in uniforms devoid of insignia began showing up on the streets of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula. After a hastily organized referendum which was seen as free, fair, and legitimate by precisely zero OECD member states, a March 18 Kremlin signing ceremony triumphantly welcomed the “Crimean Republic” as an official member of the Russian Federation.

When Levada posed the “2024” question again that November, 58% of Russians suddenly said they wanted to see Putin remain in office past the end of his fourth overall term.

In the ensuing years, even as Western economic sanctions combined with a decrease in oil prices to cut the exchange value of the ruble in half, the percentage of Russians who said they wanted Putin to maintain power past 2024 continued to rise, topping out at 67% in August 2017.

However, after Putin’s fourth official election victory in 2018, the “Crimea Effect” began to fade. Although the Russian Federation changed its constitution in July 2020 to allow for its incumbent president to legally remain in office for two additional terms, by September 2021 only 47% of Russians said that they hoped to see Putin exercise that option when he came up for re-election again in 2024.

NEWSWEEK/MICHAEL WASIURA

With no clear protocol for succession in place, Putin needed a big win—something capable of shifting domestic Russian attitudes back in his favor. In that sense, and perhaps in only that sense, his failed attempt to conquer Ukraine has been a smashing success—with the Russian public. When the same independent pollster posed the “2024” question yet again in May 2022, three months into Putin’s three-day “special military operation,” it registered an all-time high of 72%.

Now, with winter in firm control of the Ukrainian countryside, the two sides find themselves locked in a World War I-style trench warfare battle in the Donbas, with fearsome daily artillery duels, enormous casualties, and gains measured in meters, not kilometers. But with spring only months away, a much-anticipated Ukrainian offensive, bolstered by a fresh supply of modern Western weaponry, could put Russia’s hold on Crimea in jeopardy.

That raises the question: can Putin’s presidency survive the loss of the peninsula that largely legitimized his past eight years in office?

The Dictator’s Dilemma

Vladimir Putin has the power to rig elections, to manipulate constitutions, to steal tens of billions of dollars, order tens of thousands of Russian soldiers to their deaths, to poison political opponents, and to accuse the wider Western world of “Satanism,” all while maintaining an approval rating that any legitimate democratic leader would envy—still 79% overall, according to Levada polling data released in December 2022.

The explanation for this seeming paradox is simple enough to decipher: Vladimir Putin, like Benito Mussolini, Nicolae Ceaușescu, Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi, and countless others before him, is not a democratic leader. Such figures appear invincible until suddenly they don’t, at which point they often die quickly and painfully.

“Putin is a good tactician, but he was never and is not a strategist,” Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Russia’s richest man until a 2003 public spat with Putin landed him in a prison colony, told Newsweek.

“Everything he does is a tactical maneuver to hang on to power,” Khodorkovsky explained. “The consequences of this for the country have been severe, and the consequences for Putin personally, in the event that he does not have time to die before everything he built crumbles, will also be severe.”

For more than 23 years, Putin has accomplished his chief aim—staying in power—by building a Potemkin façade of democratic normalcy. His numerical popularity is due less to any personal charms or statesmanlike competence than to a system of governance intent on ensuring that any figure capable of challenging the top boss’s authority never gets that opportunity.

Natalia Arno, who headed the International Republican Institute’s operations in Russia until 2012, when Federal Security Service (FSB) officers showed up at her door to warn her at gunpoint that she had 48 hours to leave the country, told Newsweek how the Russian presidential election machinery works.

“Political actors who support the president are permitted to put their name on the ballot and to nominally run against him,” Arno said, “but whenever a person arose who actually wanted to challenge the system, they always ran into bureaucratic barriers.”

“Maybe the Central Election Commission would find a problem with the signatures that the candidate collected in order to register,” she explained, “or maybe the candidate would be charged with a crime based on questionable evidence, but something would always happen—that’s managed democracy.”

MICHAEL WASIURA/NEWSWEEK

Inside a rigged system

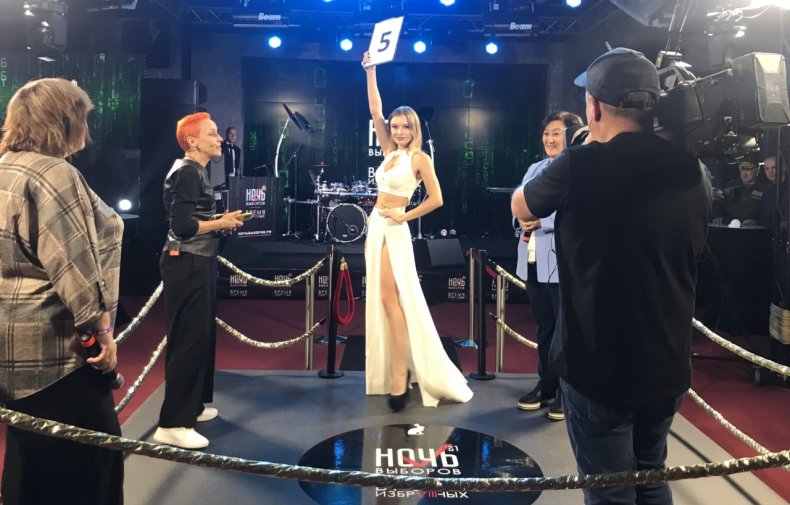

Managed democracy, which exists in Belarus as well as in Russia, is meant to provide all the trappings of political legitimacy—parties, candidates, debates, campaigns, made-for-TV electoral suspense—without actually putting the incumbent officeholder at risk of losing power.

Following that form, the runner-up in each of Putin’s four elections has been the candidate from the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, which draws its support largely from the same demographic group that backed the U.S. Tea Party movement of the early 2010s: older, small-town, archly conservative voters, nostalgic for the good old days of the Cold War.

A plethora of even less appealing options, from the fecklessly liberal Yabloko block to the neo-fascist Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, have also proven themselves unattractive and unelectable enough to secure their officially recognized place in the Russian political system. They are permitted to participate in elections so long as they do so ineffectively.

The reason why no Russian political figure has succeeded in rallying anything close to a majority of Russians behind an anti-Putin movement is because any Russian political figure capable of doing so has either been co-opted, imprisoned, driven into exile, or murdered.

Alexander Kazakov, an advisor to the officially registered political party “A Just Russia — Patriots—For Truth,” explained from the inside how the system works.

“Political power in Russia has always been in the hands of an unofficial decision-making center tasked with providing for stability, sustainability, and predictability,” Kazakov told Newsweek.

He pointed out that this has been the case in Russia since the reign of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century.

“Today it is the same—there is the Presidential Administration,” Kazakov said. “When a figure emerges who threatens the current political structure, the Presidential Administration simply does not permit that person to participate in the political process. That is how stability in the system is maintained.”

Konstantin Zavrazhin/GETTY IMAGES

In 2013, Russian anti-corruption blogger and political organizer Alexey Navalny was sentenced by a court in Kirov region to five years in prison for embezzlement in a case which the European Court for Human Rights (ECHR) later concluded had constituted “the singling out of dissidents in order to silence them by means of criminal proceedings.”

The guilty verdict provided the Central Election Commission with all the justification it needed for refusing to accept any of the threatening political figure’s petitions to officially register his candidacy in national elections. However, Navalny’s continuing anti-corruption exposés of key Kremlin figures, which garnered millions of YouTube views while bringing thousands of protesters out onto the streets of nearly 200 Russian towns and cities, continued to pose a problem—and a threat to Putin’s power.

“Navalny was able to identify corruption as the focal point of the failings of the system that Putin has put in place,” Vladimir Ashurkov, the Executive Director of Navanly’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, told Newsweek. “All layers of society—whether they’re liberals or conservatives or nationalists—are against corruption, and so Navalny’s focus on that issue allowed him to form a base of support not just in the big cities, but all across Russia.”

The Power of ‘Smart Voting’

In the early summer of 2020, when Russia changed its constitution in order to allow for Putin to remain in office until 2036, Navalny did not call for protests against the move. Instead, he focused on promoting a strategy of “smart voting” that aimed at uniting his supporters behind those official candidates who had the best chance of defeating Putin’s United Russia cronies in regional elections.

Navalny was poisoned that summer, on August 20, while on board a flight to Moscow. Subsequent independent journalistic investigations—which included one of the would-be assassins talking at length about the operation to kill Navalny— confirmed beyond any competent doubt that the FSB was responsible. Navalny survived the attack thanks to an emergency landing in Omsk, a city in Siberia, where doctors administered the nerve agent antidote atropine.

Not coincidentally, the poisoning of Navalny occurred only 11 days after a preview of Vladimir Putin’s worst nightmare appeared to be coming true. On August 9, in neighboring Belarus, where president-for-life Alexander Lukashenko had been playing the “managed democracy” game for nearly six years longer than Putin had, tens of thousands of peaceful protesters were suddenly out on the streets.

“At the start of 2020 in Belarus, everything seemed to be as stable and predictable as it always had been,” Valeriy Tsepkalo, the former Belarusian ambassador to the United States and the godfather of Minsk’s once-burgeoning tech sector, told Newsweek. “The approved opposition appeared to be under control, and the actual opposition appeared to be as isolated as ever. COVID even meant that it was not possible for politically active people to organize protests.”

However, a handful of potentially threatening opposition activists and establishment figures, including Tsepkalo himself, were already eyeing the August vote as a possibly opportune moment to finally bring political change to their little Russian satellite. One by one, they were harassed, arrested, or driven from the country.

“Lukashenko found pretexts for clearing the political field of legitimate opposition leaders, just like he always had,” Tespkalo explained. “But in 2020, Belarusian civil society was finally prepared to unite around a symbolic unity figure rather than to simply cast their ballot for the incumbent president.”

The unification of the opposition behind Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, the wife of one of the jailed activists, demonstrated that a critical mass of Belarusians had come to understand the reality of their “managed democratic” system. Throughout the campaign, Tikhanovskaya drew massive crowds all across the country, not because of her perceived capacity to govern, but because of her crystal-clear, two-plank political platform: freedom to all political prisoners (her husband included), and actual elections to be held within six months of her administration’s accession to power.

TUT.BY / AFP

On August 9, when the Belarusian Central Election Commission announced an official 80.1% victory for Lukashenko, the facade of political stability under a rigged system finally came crashing down. The country erupted in a weeks-long wave of peaceful protests, which were only suppressed when Putin declared that Russia was prepared to intervene on Lukashenko’s behalf. After enduring an estimated 30,000 arrests, countless beatings, and at least seven deaths, the protest movement ultimately dissipated.

Tsepkalo believes that the Kremlin got the message loud and clear.

“There was a high likelihood that the scenario of Belarus 2020 would have repeated itself in Russia in 2024, but with one major exception: Lukashenko had a figure like Putin to bail him out,” Tsepkalo said. “Putin, however, does not have a similar Putin capable of intervening to rescue his regime, and so in order to avoid such a scenario, he needed an external factor capable of providing him with continued domestic legitimacy.”

Tsepkalo draws a direct line between Minsk 2020 and Kyiv 2022.

“All of Putin’s utter nonsense about ‘denazification,’ ‘demilitarization,’ the cry that ‘Russians are being persecuted in Donetsk,'” he said, “was simply a pretext to get Putin a short, victorious war that would be capable of ushering him back to the kind of easy reelection that he accomplished in 2018 following the annexation of Crimea.”

Putin’s Path to War

Putin’s open preparations for a full-scale invasion of Ukraine did not begin in April 2005, when the second-term Russian president characterized the collapse of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.” They did not begin in April 2008, when NATO officially announced a Membership Action Plan for Ukraine. They did not begin in February 2019, when Ukraine enshrined the aim of NATO membership into its national constitution. They did not begin in August 2021, when the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan saw the Western-backed Kabul government fall to the Taliban in a matter of days.

Instead, after three decades of Russian bluster about NATO expansion, two decades of American foreign policy blunders throughout the Muslim world, and eight years of a Kremlin-controlled war in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region, Putin chose February 2021—five months after Lukashenko’s political near-death experience—as the moment to begin moving his tanks and troops west from Siberia.

The pre-positioning of military assets was not the only preparation for war that the Kremlin began making in the months following Lukashenko’s brush with democracy. A full year before “Z”-emblazoned tanks ultimately rolled across the border, Russia’s security services got to work dismantling what was left of the opposition at home.

MICHAEL WASIURA/NEWSWEEK

On January 23, 2021, following a months-long recuperation in Germany, Alexey Navalny boarded a Berlin-to-Moscow low-cost flight. As hundreds of his followers gathered to greet him at the Russian capital’s Vnukovo airport, his plane was diverted to Shermetyevo airport, where the threatening political figure was promptly arrested while attempting to clear passport control with his wife.

In June 2021, Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Fund was deemed to be an “extremist organization,” putting it on par with Al Qaeda in the eyes of Russian prosecutors. Russia’s once tolerated online investigative journalism sector was also targeted for destruction.

“We didn’t realize it at the time, but now it’s clear that the repression against independent journalists was connected with Putin’s desire to start his war in Ukraine,” Roman Dobrakhotov, founder of The Insider, told Newsweek. “He was clearing the field of all dissenting voices in order to remove any potential for internal opposition to his invasion.”

Putin’s ‘short, victorious war’

Now, as the one-year anniversary of Vladimir Putin’s “short, victorious war” approaches, popular disaffection inside Russia appears to be growing—not against the conflict itself, but against the ineffectiveness with which it is being waged.

When Russian media figures criticize their military’s performance, they are not doing so as part of a call to sue for peace, but as a public demand that the Kremlin leadership finally do whatever it takes to protect the Motherland from the imperialist schemings of what they refer to as the “United West.”

When arch-conservatives and ultranationalists like Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov or Wagner Mercenary Group head Yevgeniy Prigozhin confess that the campaign is not going to plan, their proposed solution is not for Russia to give up on its quest to conquer Kyiv, but for it to exercise even less humanitarian restraint than it already has when taking the fight directly to Ukrainian civilians. At the moment, there simply does not exist any viable anti-war movement anywhere near the relevant power centers in the Kremlin.

DIMITAR DILKOFF/AFP via GETTY IMAGES

A dark road ahead

Given the political landscape inside Russia, Putin’s immediate successor is unlikely to be any less hawkish on Ukraine. And even after a “Russia without Putin” eventually, and inevitably, appears on the world stage, the country will still inherit its “elected” tsar’s debts to humanity.

Alleged war crimes from Bucha to Mariupol have led to calls for a Nuremberg-style tribunal to try the Kremlin’s inner circle. Russia’s formerly respected military has been forced to turn to North Korea in order to shore up its stocks of artillery ammunition, and to Iran to supply the drones that it has used to attack Ukraine infrastructure. Meanwhile, domestic repression combined with military mobilization have sent tens of thousands of Russia’s most productive knowledge workers fleeing for refuge abroad.

While it remains to be seen whether or not Putin will physically survive long enough to witness his own political demise, his decades-long, full-scale assault on Russia’s political institutions has made one thing nearly certain: 2024 will not see peaceful crowds of pro-democracy Russians packing city streets from Pskov to Vladivostok the way pro-democracy Belarusians filled town squares from Grodno to Gomel in August of 2020.

In his all-out quest to avoid ever being overthrown in a democratic “color revolution,” Putin has all but assured that Russia’s immediate future will be anything but stable, sustainable, and predictable.

But that reality is unlikely to be widely apprehended inside Russia, where aspiring demagogues are already preparing to blame outside forces for whatever consequences Putin’s war of choice might yet have in store for the masses who have, at best, passively acquiesced to what Putin euphemistically termed a “special military operation.”

“Only if the Russian people see that we have failed in Ukraine will it become possible to open up a new political reality in which Putin no longer controls events,” Kazakov, the Russian insider, said.

“This is why Washington and London are so intent on using Ukrainian blood to defeat the Russian army,” he explained. “It is the only way they can achieve their ultimate goal of defeating Putin and, thereby, throwing Russia into chaos.”

Newsweek reached out to the Foreign Ministries of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine for comment.