About two years ago, one of my psychiatry patients was giving me particular trouble. He had depression, and despite his usual chattiness, I just couldn’t find a way to engage him on our Zoom calls. He seemed to be avoiding eye contact and stayed quiet, giving only short answers to my questions. I worried he would drop out of treatment, so I suggested that we do something I rarely do with patients: go for a walk.

We met at a park on a brisk fall day and sat on a bench when we were done. Among the few people nearby was a group of workers, who were cleaning the grounds, chatting loudly, and obviously having fun. As I tried to ask my patient about his studies, he kept breaking eye contact with me to look at the workers. Just as we were finishing, he became tearful and said that he felt very lonely. It was the most he’d opened up to me in many months, and I was relieved. Perhaps the sight of these convivial young men was a reminder of his painful isolation that he simply couldn’t ignore. Or perhaps the act of walking together had finally made him comfortable enough to open up. Either way, it never would have happened on Zoom or in my office.

My experience with my patient runs contrary to the American fixation on attention. At work, we are lauded for displaying unbroken focus on the task at hand, while some companies punish employees for taking too many breaks away from their computer. With friends, we are expected to be active and engaged listeners, something that demands nearly constant awareness. Being hyper-focused on what people are saying and trying hard not to break your attention might seem like a way to fast-forward a friendship and make meaningful connections. But in fact, that level of intensity can make you feel less connected to other people. If you really want to nurture a relationship, shared distraction might be more powerful.

If you’ve ever defused an awkward social situation with unrelated small talk or an icebreaker game, you’re already familiar with the social benefits of distraction. Indeed, a handful of studies, while not investigating distraction per se, have suggested that engaging in a shared distracting activity, such as physical exercise, can enhance feelings of social connectedness and pleasure. This is in stark contrast to the alienating, alone-together experience of people who each engage in their own distracting activity, such as staring at their smartphone.

Although the mechanism by which distraction might increase a feeling of social connectedness is unclear, there are some plausible explanations. Engaging in physical activity, even one as gentle as walking, has been associated with a substantial increase in creative, divergent, and associative thinking—perhaps because moving takes our focus away from ourselves. Creative thinking, in turn, has the potential to move the conversation along in unpredictable ways, perhaps activating the neural reward pathways that rejoice in novelty and thereby making us delight more in one another’s presence. And moving isn’t strictly necessary for the creative benefits of distraction to occur: A 2022 study published in Nature found that just taking note of one’s environment can enhance creative thinking.

That study also found that pairs working together virtually were less likely to notice their surroundings; instead, they spent more time looking directly at each other’s images. This is decidedly not good for conversation. Staring at a social partner’s face is cognitively and emotionally exhausting, and can be a sign of a domineering nature. Just as you’ve probably experienced the social benefits of distraction, you’ve also probably noticed the social drawbacks of too much intensity. Years ago, hundreds of thousands of people, myself included, went to the Museum of Modern Art to see the Serbian conceptual artist Marina Abramović’s classic performance piece, in which she sat at a small wooden table, staring silently and impassively for several minutes at the face of any visitor who sat across from her. The encounters were uncomfortable at best, and grueling at worst. By removing nearly all ambient stimulation and props, Abramović had underscored their crucial importance.

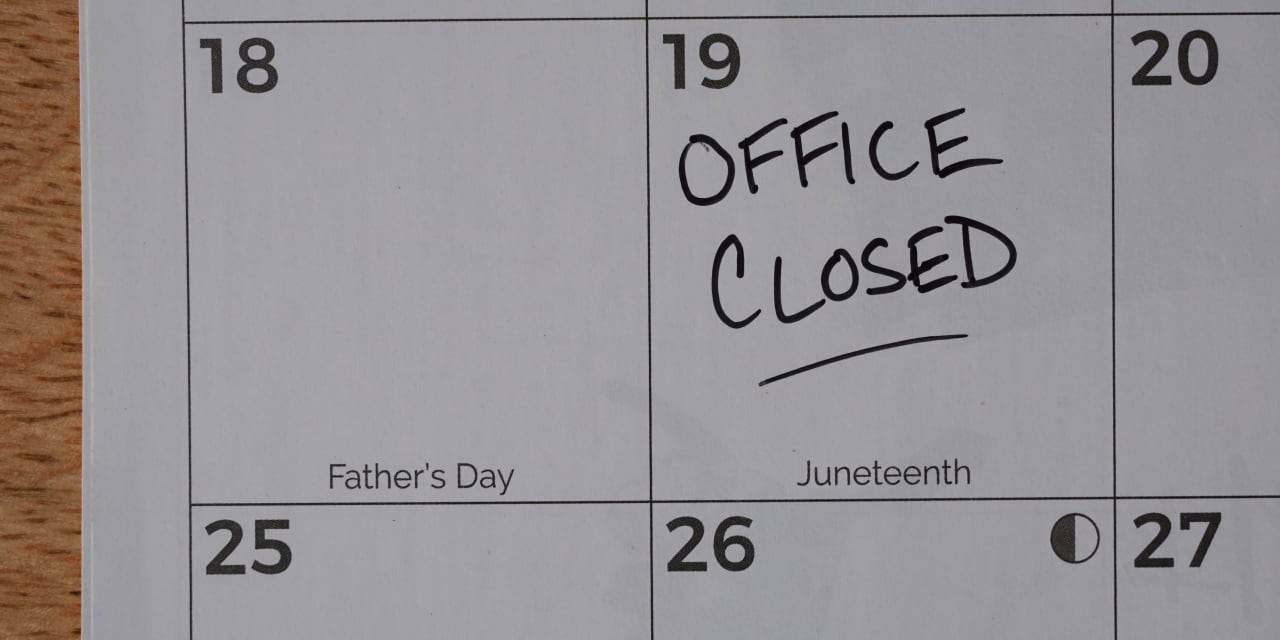

The discomfort of extended eye contact helps explain why having natural-seeming, friendship-enforcing interactions over platforms like Zoom and FaceTime can be so difficult: They largely remove the rich world of distractions and force us to stare at the face of our social partner. But for most of us, some degree of virtual connection is unavoidable. For example, a recent Pew Research Center survey estimated that more than 30 percent of employed American adults continue to work largely by Zoom, and even more on a hybrid schedule. But we can still leverage the social advantages of distraction even when we can’t physically be with friends and loved ones.

One idea is simply to turn off your camera, and thereby remove the option of staring intently into each other’s pixelated eyes. During the height of the pandemic, I taught my residents by Zoom and became very frustrated when they switched off their video. I thought they were zoning out, but perhaps they were stretching or pacing about their apartment, getting a small dose of distraction and making their Zoom experience richer. The reason it felt annoying to me was because it was one-sided; maybe we would have had a better, more creative dialogue if we had all gone off camera together. At the other extreme, try leaving your video on and picking a conversation-starting background, or taking your conversation partner on a virtual tour of your surroundings, or playing a game together. If your friend spaces out, don’t take offense as I did. Ask them what they just saw or imagined and let the conversation flow.

When you have the luxury of face-to-face contact, skip the staring contest and get out in the world together. You’ll be surprised at the places that can nurture conversation: a lively bar, a challenging fitness class, the sidelines of a riotous parade. Shouting over the noise can be a bonding experience. But be sure you don’t pick something that’s too distracting—otherwise you’ll each be in your own bubble of experience. That happened to me a few years ago, zip-lining with my husband in the Catskill Mountains. It was fun, but ultimately an exercise of being alone together. We debriefed later.

There’s a time and place for intense, focused conversation, if not intense, focused eye contact. If your friend comes to you in a crisis, or your partner is in the middle of confessing their love, they probably won’t appreciate you pointing out the guy with his pet scarlet macaw passing by (yes, I’ve had the pleasure of seeing this a few times in New York City). But mostly, we stand to benefit when we allow a little bit of the world to intrude.

Richard A. Friedman

Source link