When I was a kid, wildly inhabiting the alien worlds I made of the beaches in New Zealand, I had hair down to my shoulders and people often mistook me for a girl, or, better still, a tomboy. I must have spent as much time climbing trees as I did drawing and sewing.

My father, who I always called Dave even though he really was my father, was a homophobic, macho womanizer. Oblivious to all that, when I was about 7, I had an epiphany and marched out to tell him. There he was, leaning on the fence with a beer in his hand, talking to our neighbor who probably also had a beer in his hand. I proudly announced, “Dave, you know when a girl does boy things and they call her a tomboy? Well, I like doing girl things, so I’m a tomgirl.” I skipped away feeling rather clever, but I will never forget the look of horror, disgust and crushed manhood on their faces.

By adolescence, it was clear I had to stop the cascade of masculine traits that were pummeling, protruding from, and poisoning my body. The worst was the facial hair, which was like having an armpit on my face. It felt like a steel brush and bled every time I shaved, even with an electric shaver. Almost as bad was the hair on my arms and legs, and the small amount of hair on my chest — a stain that only I knew was there. I shaved it all off and kept that up for a while. No one but me knew that under my clothes I felt less masculine, yet not quite like a woman, which was about right. But it dawned on me that if I kept shaving, it was only going to grow thicker if I ever had to let it grow back one day. The horror of turning into Burt Reynolds made me want to dismember myself.

I bought a Ladyshave that plucked the hair out. I used it on my arms, legs and chest, and it was a disaster. I could see it wasn’t working — ripping out the roots made bleeding holes and red bumps — but I kept going and did the lot. It didn’t heal well. I looked horrendous. I finally had to accept that this Cro-Magnon pelt was going to be there no matter what I tried. It’s like being stuck in a clown suit, every single day.

This was the ’80s in England, where you could get a “sex change,” as it was known then, for free, courtesy of the National Health Service. Although even at that time I knew I didn’t want to become a woman — that I wasn’t a woman or a man — I had to do something to stop the macho mask that grew on my face every day, and the drives that made me feel too male for my own body. When I was in my teens, I went to a sex change clinic to see if they could give me medication that would reduce my testosterone and make me a “neuter,” as I called it then, since the word nonbinary did not yet exist in that context.

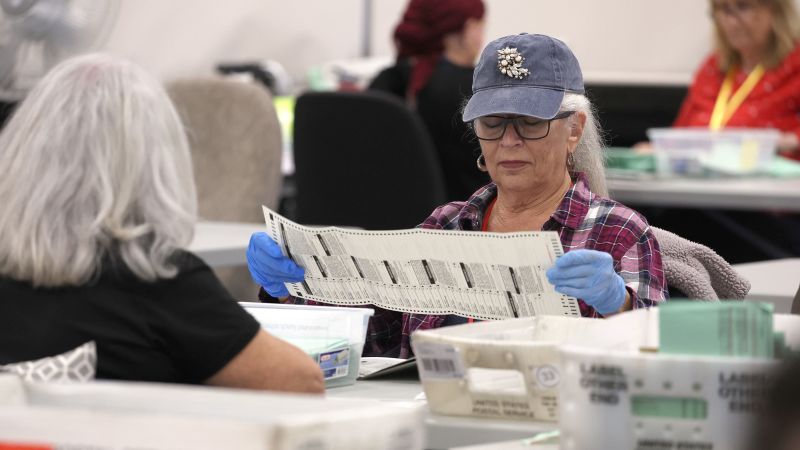

Courtesy of Adam Jesse Burns

I believed if I could just tame the relentless masculinity that pushed through every attempt I made to be neither male nor female, this would allow me to embark on a way of living that I could live with. The waiting room was like some kind of secret underground for initiates only — people in varying stages of transition, on whatever journeys they were on to become themselves outside as well as in. These were my people and it thrilled me to be with them, even though no one paid any attention to me.

The doctor turned me down. He said I didn’t show evidence of having wanted to be a woman as a child, and I was too young to make changes to my body that could have long-term repercussions. I think at that time, or in that particular practice, a person could only transition from one end of the gender binary to the other — man to woman or woman to man — as there wasn’t a procedure or protocol for making “a neither.” I didn’t qualify as a hermaphrodite either, although I envied them immensely for having a physical trait that would force people to accept that they were both male and female.

I begged the doctor — literally begged him — for something to tame the testosterone. I didn’t understand then that this wasn’t entirely the problem. It was my identity that was unmoored — my gender not my sexuality, but back then the two were conflated.

Unfortunately, “no” was the answer from the sex change clinic. It felt like, “You don’t fit, not even here. Go home and watch the game, like a man.”

I started wearing makeup, in secret at first on visits to London, then all the time once I lived there. I wore full makeup — foundation, powder, blusher, lipstick, eyeshadow, eyeliner. I painted my nails, had thick, black, curly hair down to my waist, and dressed like a gothic dandy. I was finally androgynous, or as close to it as I could get.

My father saw me as a freak of nature and kept his distance, so much the better for me. My mother was initially concerned, out of a generational protectiveness that softened to complete support as she understood what was really going on. I’ve moved around a lot, and with each move friends fell away as new ones came along, in company with the person I presented to the world.

Things were good for a while, but over time, navigating life, I let the “winner” of my genders be the one that everyone else could see. I don’t know how it happened, I just let life dilute me. I understood my male side — it just wasn’t my only side. But it became my outside, once again.

I discovered that I didn’t need to be afraid of my masculinity, that it could help me and protect me. As a teenager, I was the victim of a lot of violence because of the way I looked, and I learned to take care of myself. Later on, I lived on Greyhound buses for a year writing my first novel, sleeping in the stations, which were all downtown. I met a lot of runaways, sex workers, addicts and ex-cons — some good people. But it was a dangerous adventure that I couldn’t have pulled off without fully inhabiting my 6-foot male body and giving off a serious “don’t fuck with me” vibe. And yet my female side was — and remains — like an invisible force moving within me, that I can call on at any time.

Courtesy of Adam Jesse Burns

Nevertheless, a quiet evolution was happening. What began as a superficial burying of the feminine became an internalizing of the whole situation. Initially an unhealthy reaction, it became a strength that gave more back than I could ever have imagined. When you chip away everything except what you can’t afford to lose, you find out what you really need and who you really are. The essential me is androgynous on the inside, and whatever happens on the outside, the me without gender will never go away. It would have been impossible to stop that state from expressing itself, and so here I am after many years, returning to how I used to look back in London. The difference now, though, is that this is an expression of indifference to gender expectation, not a reaction to it.

I’m happily married to someone who fully understands me. Romy’s always thought I look good in “guyliner,” and she gets me just the way I am. Sexuality doesn’t have anything to do with my gender journey — I’m comfortably heterosexual. Romy is my lover and the love of my life, and she makes it all worth it. We share makeup, and only have a problem when we’re down to one eyeliner pencil. Life can be rocky, but it can also be Rocky Horror.

With her support, about 10 years ago, I finally did something about the chest wig that appeared on my face every day ― I had laser hair removal. It was excruciatingly painful and took a couple of sessions a week over several weeks but was worth every “Aaaargh!” No more shaving. No more Homer Simpson five o’clock shadow. Ever again.

We now live in times where the term “nonbinary” is becoming more and more understood and even accepted. I was nonbinary in the ’80s before there was a word for me. Now people use pronouns like “they” and “Mx,” which is wonderful. I’ve never felt a pull toward the term “they.” At least when applied to me, “they” feels like duobinary, when I’m nonbinary.

In an ideal world, my choice would be “it.” I don’t see “it” as derogatory, I see it as precise and singular, a recognition of individuality. I’ve used “it” with characters in my new novel and it works very well. But to be brutally honest, I don’t care what people call me. I’ve been called just about everything and it’s never hurt as much as being asked to be somebody else.

At this liminal point in our evolution, I want people to be comfortable with me as I am, not hopping from foot to foot trying to be careful around me. “It” is too much of a leap for most people. I’m concerned they think I’m joking, because no one wants to be called an “it,” right? The last thing I want is anyone thinking “Are you taking the piss?” So until the day comes where I can be accepted as “it,” I will continue to use “he” in most situations. It’s just the squeaky horn that goes with the clown shoes.

Courtesy of Adam Jesse Burns

I’m comfortable with both sides of myself, in this mix that is me. Both are present, equal, balanced. Sometimes I feel both male and female, or more one than the other, but the knowing that courses through my very existence is that this mix that is me adds up to neither. I’ve learned there are comforts in the little things that would mean nothing to anyone else, like using my full name. This gives me male and female first names, and every time I see it, I see that double shadow self that is me.

As a nonbinary person, I observe the world from a nonbinary perspective. I’m a fierce feminist and never miss a chance to ridicule a misogynist or toxic masculinity. I see unbridled (or at least unexamined) testosterone as a disease symptomatic in the destruction of our planet — and the people and the animals on it. I believe all civilization on Earth is in peril because we’re not able to look beyond our collective binary mind and see that our strength is in what we can share, not in what we can compare.

I’m realizing how long I’ve been focused on existence, unaware that all along I was learning how to be — by compromising, crashing myself, failing. I wrote in one of my books “Choices are the difference between existence and being,” and it’s true. It’s taken a journey to both ends of the spectrum to find a balance that connects my inner reality with the world I confront every day. “Become who you are,” like Nietzsche said.

So here’s a simple message, learned from a complicated life. If you feel you need to become something only you can see, do it. Do it now. Crash and burn a few times and keep on getting up, until you don’t even have to think about it any more, and you have an identity that is yours, whatever flavor of the rainbow that turns out to be. Don’t let society and family pull you in directions that are not your own. They will come around, or they won’t. But if you bend to their identities, you may never have one of your own. If your outside matches your inside, the world you meet each day must meet you on your terms not theirs, and it will be you they will meet. The real you.

Raised on both sides of the world, in England and New Zealand, Adam Jesse Burns lived in London, Barcelona, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, before calling New York City home. He lived on Greyhound buses for a year writing his first novel, “In Like Flynn,” and his second, “The House Made of Wheels,” which explores identity beyond gender. His new novel, “The Last Underground,” is a provocative dystopian sci-fi work about our urgent need to evolve beyond who we think we are. His artwork has been shown at galleries and clubs in London and Santa Fe. He works as a designer in New York City. He has a B.A. in literature, art & film, cum laude, from CUNY, is vegan, and is nonbinary (he/it). Visit his website, adamjesseburns.xyz, for more info.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.