Kimberly Miller has worked with people on Denver’s streets for years, so she was ready for a somber evening when she arrived at the City and County Building Sunday night. It was the winter solstice — the longest night of the year — when the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless (CCH) held its 36th-annual vigil for people who died this year without stable housing.

She did not expect that it would feel so personal. Before the program began, she spied the name of someone she knew written on one of the 276 luminaries glowing on the stone steps. It was a woman she’d once helped, then lost touch with. She was crushed to find out like this that the woman had died.

“Oh my God. Trena. Trena’s gone,” she remembered thinking. “These are our people. These are our neighbors. And it makes my heart so heavy.”

Each solstice, service providers read the names of people who died in homelessness over the last year.

The Coalition’s list for 2025’s remembrance was shorter than the last, marking a second decline since the nonprofit recorded a record 311 deaths in 2023. It’s a positive sign for a city that has struggled to address visible poverty for decades. Still, many are worried that momentum might run out next year.

The trend was a silver lining around a somber event.

As each name was read Sunday night, the crowd responded together: “We will remember.”

Cathy Alderman, spokesperson and policy lead for CCH, said the event has always been about providing last rites to people who didn’t get them.

“Many of these people won’t otherwise have a ceremony in their honor, and so we do it together as a community,” she said.

Data Source: Colorado Coalition for the Homeless

Alderman said CCH generates its numbers each year with help from Denver’s Office of the Medical Examiner, which cross references names with a database of services for homelessness. Then, CCH canvasses other service providers to find cases that didn’t make the medical examiner’s list. CCH’s numbers are always higher than the city’s official count.

Though this second drop in recorded deaths was good news, numbers are still well above pre-COVID levels.

But Alderman said Mayor Mike Johnston’s work to address visible poverty, namely opening hotels as shelters, likely played into the reversal.

“The non-congregate shelter sites have brought more people inside, and that is a good thing. And I do think that that has contributed to fewer deaths outside,” she said. “But what I think that also screams to us is that we can’t now stop providing those spaces, or roll back the ability to provide those spaces, by not providing the funding and the support to the providers.”

The city has been touting successes this year, but many are uneasy about the future.

Early this year, Mayor Johnston took credit for numbers that claimed an unprecedented drop in unsheltered homelessness, even though housing insecurity grew overall. His administration celebrated the completion of new affordable apartments. They said nobody died “as a result of cold weather exposure” last winter, which spokesperson Jon Ewing said was the first time that’s been recorded in Denver.

Then again, Alderman said on Sunday: “Look at all the names here.”

Cold weather was likely a contributing factor to the deaths remembered here, she said, even if it wasn’t listed as the official cause. And though the city has made strides in a positive direction, economic pressures are sure to complicate things next year.

She worries proposed Medicaid cuts could force more people into homelessness. Federal threats to slash spending on “housing-first” services means cities could have fewer resources to work with. Denver has already begun to rely more heavily on short-term, locally-funded housing vouchers instead of permanent funding provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Denver’s own budget crisis has eroded programs meant to keep people housed.

“We’re also very concerned about the state budget, because there are going to be significant gaps,” Alderman added.

Jessica Ehinger, CEO of the Colorado Village Collaborative, whose tiny home villages inspired Johnston’s plans, said her organization is preparing for less capacity next year. One of her villages will close next spring because of cuts in Denver’s budget. Her concerns about the future have tempered her perspective on any positive progress.

“It is absolutely very frustrating. I think that’s the message that we’ve really been trying to relay to the city, to funders, that I don’t think we’re at a point to make a victory lap,” she said before the vigil began on Sunday. “I would love to imagine that we’re going to put ourselves out of business the next few years, but again, with everything that’s happening, especially at a federal level, it’s really hard to imagine that happening.”

Meanwhile, Johnston’s critics are growing louder.

Kimberly Miller met Trena, the woman whose name was read into the dusk on Sunday, two years ago in a blizzard. Trena and her partner, Ray, were struggling to find somewhere warm to sleep when Miller and other volunteers arrived with a van.

Miller said police showed up next and arrested Ray.

“They have him in the cop car, and he’s her caregiver. She’s in a wheelchair. Meanwhile it’s a snowstorm and I have her in my car,” she remembered. “What am I going to do?”

Police intervention has long been a controversial part of Denver’s response to homelessness, and Mayor Johnston has signaled he will lean more on law enforcement in the future.

Miller is a volunteer with Mutual Aid Monday, which feeds people outside of city hall each week. As the city works to prevent tent encampments from appearing, she said advocates like her have seen people scatter instead to darker corners of the city. People are hiding, she said, and she worries that will cause more outdoor deaths.

“They’re dispersed and driven more into the margins and the shadows. And then with that comes a full on hardcore enforcement of the camping ban, so that people can not even be on the sidewalk with a blanket or a tarp, let alone a tent,” she said. “I feel like it’s almost back to square one, where we were with Mayor Hancock in some ways.”

So there was some irony when Colorado Coalition for the Homeless CEO Britta Fisher invited anyone who needed warmth to grab a free blanket on Sunday night. CCH partnered with the Homeless Remembrance Blanket Project this year, who laid out over 600 hand-made quilts on Bannock Street as a symbol of the country’s ongoing housing crisis.

“They’re just going to get taken away,” someone in the crowd said.

When Fisher thanked the city for its partnership in helping to address homelessness, there were audible groans and boos from the crowd.

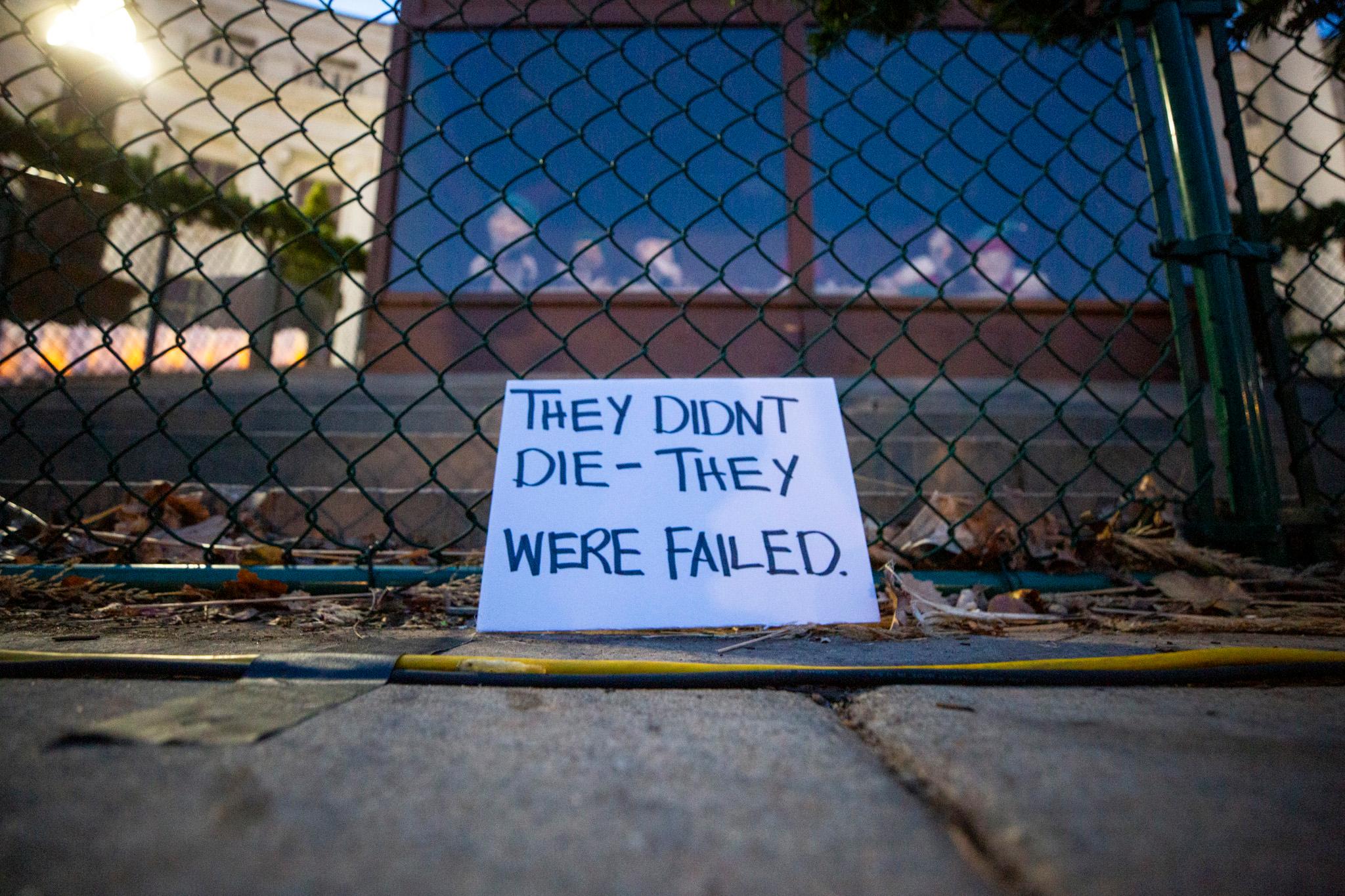

Someone dropped protest signs in front of the luminaries. One read, “They didn’t die — they were failed.”

Still, when it came time to read the names, everyone in the crowd joined in to repeat “we will remember” together. As the city reckons with existential pressures and internal division, Miller said it’s as important as ever to center the humanity embedded in these debates.

“Behind every name is a life and a story,” she said. “It makes me more determined than ever to fight for justice for people that are forced to be on the streets.”