When I had my first baby, it went well, all things considered. I was induced at noon, gave birth 15 hours later in the wee hours of the morning, and my beautiful little boy went right on my chest, snuggling in and latching. I remember him just gazing up at me endlessly, taking in my face. Eventually we were moved to a private room, and I went to a breastfeeding lesson just down the hall, before the grandparents arrived to meet him. Through all the commotion, my blissed-out baby boy slept soundly, swaddled in the bassinet beside me, just like I’d imagined he would.

That night, I sent my husband home, after watching him restlessly toss and turn on the recliner in our room. (He’s 6’4″.) “You go home, check on the house, get some rest, and come back in the morning,” I said. “I’ve got this!”

Cue the narrator: I did not, in fact, have this.

My baby, like many, “woke up” on night two—he was alert, hungry and very pissed off about not being in his warm, snug womb. He cried incessantly unless I stood up and swayed him, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth. (This “night two” phenomenon—when the baby becomes more alert, and the mom’s milk hasn’t come in yet—is so well known that it was actually written up in the booklet the hospital had given us after birth, but I had been too distracted to read it.)

After an hour or two of the swaying, I decided I needed a break and walked out to the nursing station to hand off the baby. To my surprise, the nurse I found didn’t take him—instead, she gave me a warm blanket to swaddle him in, patted me on the shoulder, and said, “you’re doing all the right things.”

So I returned to my room. It was now 30 hours and a labour away from the last time I’d really slept, I was bleeding profusely, and I was again swaying my little baby, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth. The shadow from the hall lights flickered on and off of his face, and he blinked up at me, silent, but very awake.

A thought hit me: Was this what motherhood was going to be? Me, doing whatever this baby needed, no matter the mental-health costs to me? (Spoiler alert: Yes—for the next little while at least.)

When I told my own mom about all this, she was shocked at how different my experience was from how she was treated when she’d given birth to me, in the 1980s. Back then, she’d stayed in the hospital for five days, and every night the nurses whisked me away to the nursery so she could rest, bringing me back to breastfeed twice. When they got home, my parents gave me a bottle of formula every night, just in case my mom wasn’t making enough breast milk.

This generational switch has happened in response to mounting evidence that supports what’s called “rooming in”—where mom and baby are kept in the same room—and promoting exclusive breastfeeding. That means more support and encouragement around breastfeeding, not having nurseries available to healthy infants, and a lot of grumpy babies on night two.

During COVID-19, it’s also gotten harder: most hospitals allow birthing people only one support person, and no visitors. That often means moms can’t have a doula, or your own mom, as well as a spouse. At times, COVID restrictions have also dictated that both mom and their partner are not allowed to even leave the hospital room—no going to grab food, no smoke breaks, no in and out privileges. The pandemic has also raised the bar for when a baby would be sent to the nursery or taken care of at a nurses’ station.

Postpartum people are also getting sent home from the hospital faster—the average stay has dropped by 30 per cent since the pandemic began.

The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, which was started by the World Health Organization in 1992, has also helped push these changes forward, well before the coronavirus hit. Twenty-nine hospitals across Canada are certified as “baby friendly,” meaning they follow the 10 rules set out by the WHO, including training staff to help mothers breastfeed, ensuring moms are told the benefits of breastfeeding, rooming in, not giving pacifiers, encouraging feeding on demand, and doing skin-to-skin after birth. And hospitals with this designation have to refuse money from formula companies, refrain from advertising formula, and cannot offer it unless it’s medically necessary.

This could be seen as shifting birth back to where it should be: not unnecessarily separating moms and babies, and supporting breastfeeding as the default way to feed a baby. Many moms love it, in fact. When I asked for thoughts on a few Facebook groups for parents, one mom replied, “You try and take my child out of my room after giving birth and I’ll wrestle you to the ground, grannie panties and all!”

Another said that after doing a lot of research while pregnant, she went to her doctor with a list of evidence-based requests, like doing skin-to-skin, and was reassured to hear that they were all standard at the hospital she was going to.

But others, like me, have a more mixed experience. Alli Glydon, a mom from Calgary, is one. When she gave birth, she had a scheduled C-section because her baby was breech. She ended up having a reaction to the spinal block they gave her, and was violently ill for eight hours afterwards.

Then, she had trouble breastfeeding, and the nurses encouraged her to wake up every couple of hours to hand-express a few drops of colostrum to give her baby. She would later find out that her baby had a tongue tie, small mouth and high palate, which was why nursing was so difficult. Additionally, Glydon had low supply and Reynaud’s syndrome, which can make nursing incredibly painful.

“My daughter was obviously hungry—she was rooting and wouldn’t latch at all—and I couldn’t hand express anything beyond one to two drops of colostrum. The nurses were taken aback when I asked for formula, and it took a long time to come—like more than 30 minutes,” she says. “I felt like I had to beg for it.”

Talia Bender, a mom in Vancouver, also had a negative experience. After a 25-hour labour, she was moved into a room with her baby. That night, when she was on her own (her husband was home with their older kids), she was exhausted and nursing the baby when they both fell asleep. “The nurse came in and yelled at me, saying, ‘This is so unsafe,’” she says. “And it’s like, I can hardly walk, I just pushed a watermelon out of my vagina, and we both fell asleep because I’m so exhausted. And you weren’t here!”

Bender says she feels like leaving moms alone like this, postpartum, is abnormal. “When you think about birth in the past, you had midwives and your family and a support system; all the women would be there to hold the baby, and let the new mother recover,” she says. “Now we have hospital births and families live all over the place, and there’s so much pressure on the new mother, and so much disregard for the recovery process.”

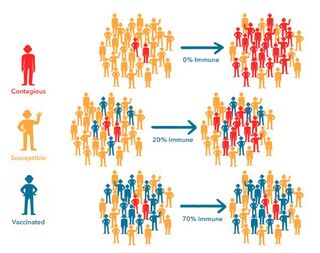

The question of whether the Baby-Friendly Initiative has gone too far has been making headlines lately thanks in part to a U.S. organization called Fed is Best. Founded in 2016, Fed is Best argues that hospitals are encouraging breastfeeding over health, and putting babies at risk of dehydration, jaundice, hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) and hyponatremia (low sodium).

“There are billions of infants who require formula at some point during their first year of life,” says Fed is Best co-founder and physician Christie del Castillo-Hegyi. “To hide that and give parents an illusion that exclusive breastfeeding is possible, natural, easy and ideal for all infants, without any evidence, and no parsing out or informed consent of the harms—it has created a public health catastrophe,” she says.

Through its website, Fed is Best collects and publicizes stories like that of Landon, a healthy baby who died at 19 days old of cardiac arrest from not eating enough. “If I had given him just one bottle, he would still be alive,” reads the heartbreaking headline on the story.

In a 2016 JAMA Pediatrics publication, paediatrician Joel Bass also raised concerns about the unexpected consequences of rigidly enforced baby-friendly practices, including the focus on strict breastfeeding exclusivity. Bass says every hospital should have a nursery for healthy babies, so moms have the option to send their babies there to rest, and that offering a small amount of formula in the early days of life isn’t likely to impact breastfeeding success.

He also points out that while many breastfeeding-friendly hospitals still discourage pacifier use, newer evidence shows that it doesn’t interfere with breastfeeding—and may even encourage it—and that putting babies to sleep with a pacifier can help prevent Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

But others point out that the Baby-Friendly Initiative does allow for formula when medically necessary. “There are babies that need formula—there are medical reasons for supplementation—and it’s perfectly fine,” says Hiltrud Dawson, a nurse and lactation consultant who works for the Baby-Friendly Initiative of Ontario. “I believe that babies are given formula when needed.”

It’s also important to remember that when it comes to following up with babies who are losing weight after they leave the hospital, Canada has a much better safety net than the U.S. does, says Merilee Brockway, a registered nurse and lactation consultant who studies the effects of human milk on babies. That includes babies seeing their doctor or a public health nurse within a week after leaving the hospital—that’s when a newborn is weighed and professionals help parents make sure breastfeeding is on track.

Because of the time crunch in getting mothers home, parents are also not always sent home with enough information, says Dawson. In response, her group helped create a card with information for new moms about how to make sure their baby is getting enough— including how many wet diapers they should look for, the change in baby’s poop, and that their babies should gain weight from day four onwards. They should also have a strong cry, be active, and wake easily.

If your baby is getting enough, there do seem to be benefits to not offering any formula at all, says Brockway—even if this isn’t exactly helpful information for new parents who are already stressed enough about exclusive breastfeeding (EBF). “We can see significant differences in the gut microbiome after even one formula supplementation,” she says. Researchers have indeed found a connection between the gut microbiome and issues like asthma and obesity—but there isn’t enough research yet to confirm exactly how that connection works, or how much formula-feeding would affect it.

Brockway adds that there is also lots of evidence about how mom’s mental health is important to raising a happy, healthy baby—and that if mom is really suffering under the strain of trying to breastfeed, that can be reason enough to supplement. And she says some health-care professionals can be a bit “fanatical” about encouraging moms to breastfeed. She would like to see the mantras of “breast is best” and “fed is best” replaced by a new one: “informed is best.”

“We have really high breastfeeding intention rates and breastfeeding initiation rates in Canada. Most moms want to breastfeed. But breastfeeding can be really hard, and if you have a difficult labour, or if mom’s sick, it gets to be really really difficult,” she says. “We need to be able to say, ‘Are we forcing mom to carry on this path?’ We need to respect maternal autonomy.”

Vanessa Milne

Source link