Meat has a bad reputation. Most people think of meat, especially red meat, as dangerously unhealthy. However, meat has unique properties that make it more nutritious, easier to digest, and less likely to irritate your body than vegetables. Does the science behind meat-phobia hold up under the microscope?

Is red meat less healthy than other kinds of meat?

Meat is made of animal muscle fibers, which come in two major types: fast and slow. Dark muscle fibers (“slow” fibers) are designed for endurance activities, whereas light muscle fibers (“quick” fibers) are designed for rapid bursts of activity and tire easily. Therefore, dark muscle fibers have greater energy needs. For muscles to make energy, they need an energy source (fat), oxygen to burn the fat, and vitamins and minerals to run the reactions that release the energy from the fat. Therefore, dark meats usually contain more more fat, vitamins and minerals than light/white meats.

To hold the oxygen, dark (slow) muscle fibers need larger amounts of an oxygen carrier protein called myoglobin. Myoglobin is red, which is why red meat is red. Myoglobin is rich in iron, the mineral that binds oxygen, so red meats contain more iron than white meats. Because most dark meats contain more fat than light meats, they can be higher in calories. However, because dark meats also contain more minerals and B vitamins, they are actually more nutritious than light meats.

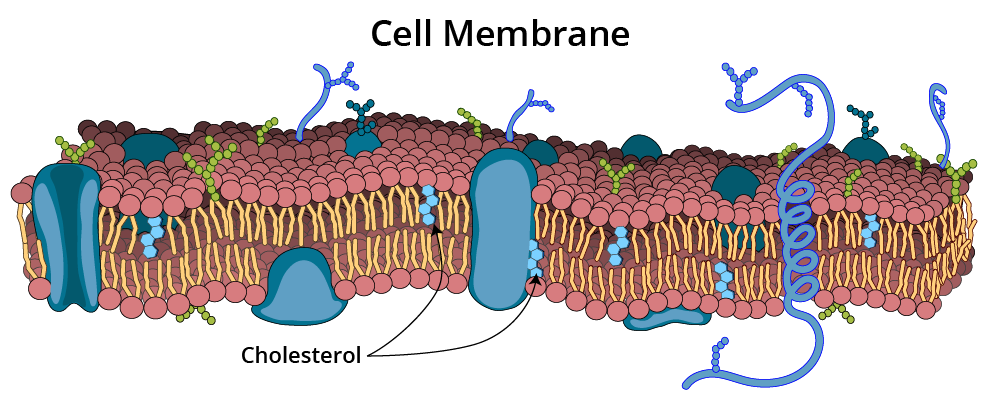

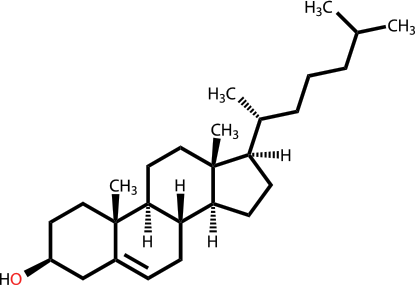

Did you know that all types of meat—red, light, and white—whether from mammals, birds, or fish—contain about the same amount of cholesterol? There is no more cholesterol in a pound of steak than in a pound of chicken.

But doesn’t red meat increase risk of death?

A study conducted at the Harvard School of Public Health [Pan 2012] claimed that eating red meat increases our risk of death from all kinds of diseases, including heart disease and cancer. This was an epidemiological study, which, by its very nature, is incapable of proving cause and effect; therefore, even if it were the best epidemiological study ever done on the planet, it would be impossible for the authors to conclude that red meat causes death.

Below are just two of the problems I noticed in this study:

- There were two huge groups of people in this study: the Nurses’ Health Study (over 120,000 women) and the Health Professionals Follow-up study (over 50,000 men). Every 2 years, the nurses were asked how often they had eaten red meat over the past 2 years. Every 4 years, the male health professionals were asked how often they had eaten red meat over the previous 12 months. Can you imagine? Even though I keep track of what I eat in a daily food record, if you asked me what I ate LAST WEEK (never mind 1 to 2 years ago), I honestly couldn’t tell you. Naturally, these questionnaires can’t tell us how often people forget, underestimate, or perhaps even lie about what they were actually eating.

- It just so happened that the people who reported eating the most red meat per day, also happened to be more likely to:

- smoke cigarettes

- be sedentary

- weigh more

- have diabetes

- take aspirin

- eat more calories per day

- drink more alcohol

- eat more dairy products

These are all excellent examples of what researchers call “confounding variables.” Confounding—translation? Confusing. Even if all of the data are accurate, how can we really know whether the people who ate more red meat were more likely to die because of the red meat, or because of one or more of these other issues?

For a more detailed critique of this study, please see Gary Taubes’ excellent blogpost, entitled “Science, Pseudoscience, Nutritional Epidemiology, and Meat.”

Are saturated fat and cholesterol bad for my heart?

Numerous studies by cardiology researchers have finally disproved the myths that dietary fat, meat, and cholesterol cause heart disease. In fact, some of the healthiest diets in human history have been very high in meat and animal fat. To read more about this topic, please see my post “The History of All-Meat Diets.” We have been eating animal meats, animal fat, and cholesterol for about two million years, but heart disease has only been a major problem for us for about 50 years. The major culprit is therefore much more likely to be something that is NEW in our diets; the current evidence points most strongly to refined and high glycemic index carbohydrates, not fat, meat, or cholesterol. To read more about how sugar raises “bad” cholesterol levels and why dietary cholesterol is not bad for you, please see my cholesterol page. To read more about the connection between sugar, insulin resistance, and heart disease, please see my post “Why Sugar is Bad For You: A Summary of the Research.” To see an example of how researchers desperately twist logic in an effort to connect red meat to heart disease, please see my post “Does Carnitine From Red Meat Cause Heart Disease?“

Does red meat cause cancer?

If meat is so carcinogenic, why was cancer so uncommon until the last century or so? We are not eating any more meat now than we did a hundred years ago, yet cancer incidence is skyrocketing. So, why do we believe that meat causes cancer?

There have been numerous research studies claiming to tie red meat to cancer (particularly colon cancer), however, these were weak epidemiological studies, and are not representative of results in the field as a whole. The fact is that studies of meat and cancer yield very mixed results. Many studies show no connection at all between meat and cancer, and some studies even show a protective benefit. There is simply no solid scientific evidence to support the belief that red meat increases cancer risk.

This did not stop the World Health Organization (WHO) from proclaiming to the planet in October 2015 that red and processed meats cause cancer. Unfortunately, the WHO report is all smoke and mirrors. To see what I mean, please read my detailed analysis of the WHO report: “WHO Says Meat Causes Cancer?“

Charred meats and cancer

Charred meats and wood-smoked meats contain “PAHs” (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) and “HCAs” (heterocyclic amines). PAHs and HCAs have been shown to cause cancer in lab animals. Studies in humans are limited to epidemiological studies, and even these have been inconclusive.

PAHs are present not just in charred meats, but also in anything organic (plant/animal matter) that has been burned–from cigarettes to forest fire smoke to automobile exhaust. PAHs are also present in many other foods, such as cereals, vegetable oils, cheese, and coffee. In fact, cereal products, not meats, are the biggest sources of PAHs in the typical diet.

HCAs, on the other hand, can only be formed from protein-rich foods, such as meat, fish, and poultry.

Grilled and fried chicken can contain even higher amounts of PAHs and HCAs than grilled red meats, yet studies have shown no connection between poultry intake and cancer.

Nitrates and nitrites in processed meats

Nitrates and nitrites are used in the production of processed meats like bacon, salami, and ham. However, they are also found naturally in many plant foods, often in very high amounts. For example, pound for pound, spinach contains at least 30 times more of these compounds than hot dogs do (see table to the left). In fact, some manufacturers of processed meats boast that they use celery powder (very high in nitrate), instead of the more commonly used sodium nitrite to preserve their meats.

What is the difference between nitrates and nitrites? It can be confusing because these terms are often used interchangeably by food manufacturers, physicians, and nutritionists. The reason why people lump them together so often is because nitrates easily turn into nitrites in foods and in the body. Nitrates and nitrites are very similar chemical salts with very similar properties, and mixtures of nitrates and nitrites are often used in food processing. Nitrites are about three times more potent than nitrates as preservatives.

In combination with salt, nitrates and nitrites prevent the growth of the bacteria that causes botulism (a type of food poisoning). They also act as antioxidants, keeping the fat in the meat from turning rancid, and giving the meat an unnatural pink color. Nitrates and nitrites themselves have not been shown to cause cancer; however, they can react with proteins in the meat to form nitrosamines, which are known to cause cancer in laboratory animals. The addition of special antioxidants during processing cuts down on this chemical reaction and reduces the amount of nitrosamine formed, but doesn’t eliminate it completely. Therefore it is best to choose fresh, unprocessed meats when possible.

It may also be wise to limit intake of vegetables that are very high in nitrates, such as spinach and celery. Bacteria in our saliva convert vegetable nitrates into nitrites, which we swallow. These nitrites can then react with proteins in our stomach to form nitrosamines, exactly the same way they do during meat processing. These nitrosamines are potential carcinogens; this is why some researchers believe that diets high in nitrates are associated with increasing rates of stomach cancer.

Will animal protein damage my kidneys?

To the best of my knowledge, there’s no clinical trial evidence for it so far. The human kidney is designed to be able to handle large quantities of animal protein, perhaps because our ancestors would have sometimes needed to eat large amounts of meat at one sitting, instead of eating smaller portions several times per day every day, the way we modern people do.

The vast majority of studies suggesting a connection between high protein intake and kidney damage have been conducted on laboratory animals or have been epidemiological studies. A 2011 review of the research [Odermatt] examining the connection between diet and kidney disease cited only a single human clinical trial designed to explore this question, and the results were very reassuring:

“Serum creatinine levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate did not change in individuals with normal renal function after 1 yr of a low-carbohydrate diet with higher protein (35% kcal from protein compared with 24%) and fat intake (61% compared with 30%).”

A study done in 1930 of two men who ate a 100% meat diet for a full year revealed no signs of kidney problems whatsoever. [McLellan]

Meat is the only nutritionally complete food

Animal foods (particularly when organ meats are included) contain all of the protein, fat, vitamins and minerals that humans need to function. They contain absolutely everything we need in just the right proportions. That makes sense, because for most of human history, these would have been the only foods available just about everywhere on the planet in all seasons.

Below you can see that animal products are superior sources of most essential vitamins and minerals, including 4 that do not exist in plant foods at all:

Meat nutrients are ready-to-use.

In contrast to vegetables, meat does not contain any “anti-nutrients”, like cellulose, phytates and tannins that interfere with digestion or absorption of vital compounds such as vitamins and minerals.

The forms of vitamins and minerals in meat are the easiest forms to absorb:

- “Heme” iron, the form of iron found in meat, is at least 3 times more available to our bodies than “non-heme” (vegetable) iron.

- Vitamin A from animal sources is 12 to 24 times more available to us than vegetarian sources.

- Vitamins B12 and K2 are only found in animal foods.

Meat is naturally low in carbohydrate

This means that it is impossible to eat meat and generate a significant insulin spike. Insulin spikes are to be avoided as much as possible, as they seriously destabilize our brain and body chemistry and can lead to inflammation, cell damage, disruption of cholesterol and fat metabolism, and numerous chronic diseases.

Meat is gentle on your delicate system.

While vegetables protect themselves with chemicals that are potentially harmful to our cells, animals protect their meat with claws and fangs, so meat itself does not contain any irritating substances. Meat is an especially friendly choice if you tend to be chemically sensitive.

Is meat hard to digest?

Quite the opposite. Meat is efficiently broken down by our own natural enzymes, so we do not need to rely on intestinal bacteria to help us digest it. This means that there are virtually no intestinal gases produced in the process. Meat is efficiently absorbed by our intestines, so there is very little wasted. The belief that meat contributes to constipation is a myth. Unless you have a specific sensitivity to a certain type of meat, you will have no trouble digesting it. Meat can, however, become “trapped” in your digestive tract behind sluggish high-fiber plant foods and dairy products, which are very difficult to digest.

What about meat and gout?

Please see my blog article: “Got Gout but Love Meat?“

Can eating meat cause iron overload?

I find no evidence in the scientific or medical literature linking meat consumption to iron overload. It is true that too much iron can be toxic to cells, and it is true that the body has no way to get rid of excess iron other than through the shedding of skin and intestinal cells or through bleeding. However, the body is very smart and knows not to absorb too much iron. The liver releases a hormone called hepcidin which monitors our iron status and tells our intestinal cells exactly how much iron to absorb. On average, we lose 1 to 3 mg of iron per day, so this is approximately how much we absorb.

Every article I found about iron overload in humans, including an excellent 2012 review in the New England Journal of Medicine, had to do with health conditions that disrupt normal iron metabolism, not with simple overindulgence in red meat. These include hemochromatosis and other genetic disorders of iron metabolism, certain enzyme deficiency disorders, liver disease (alcohol-induced liver damage, viral hepatitis), multiple blood transfusions, and iron supplement overdose (as opposed to red meat overdose). There is also a common non-genetic health problem that can disrupt normal iron processing in the liver called “dysmetabolic hyperferritinemia.” DH is seen in some individuals who have severe metabolic syndrome, usually with fatty liver. While iron deficiency is a very common diet-related condition, diet-induced iron overload does not seem to exist in otherwise healthy people.

What types of meat are healthiest to eat?

Healthy, naturally-raised animals fed their natural diets produce meats with healthier fat profiles, including higher levels of essential omega-3 fatty acids than grain-fed animals.

Avoid factory-farmed, grain-fed animals when you can. Whenever possible and affordable, choose meat products from naturally-raised animals. This means animals that have been fed a diet most similar to what they would eat if they were living in the wild:

- Cows/Lambs/Sheep—grasses

- Chickens—grasses, insects, worms

- Turkeys—grasses, insects, seeds, small animals

- Ducks/geese—fish, grass, algae, insects, fruits

- Pigs— grasses, root vegetables, fruits, nuts, insects, worms, small animals

- Fish—wild, not farmed. Food varies depending on species.

Poultry sellers often boast that their birds are fed an all-vegetarian diet, but if you notice above, birds are naturally omnivores and eat small creatures for protein and fat (worms and insects, for example). This is why backyard birds enjoy suet (animal fat) in the wintertime—insects and worms are scarce in winter and they need the fat and protein for energy.

Does Meat Quality Matter?

It is best for human health, environmental health and animal health and welfare reasons to choose meats raised humanely and sustainably from healthy animals being fed a species-appropriate diet: pasture-raised land animals, wild-caught seafood and wild game. However, not everyone can afford or consistently access animal foods that meet all of these criteria.

Purchasing meat, poultry, and eggs from local community supported agriculture organizations or from responsible online seafood, poultry and red meat distributors can be a reasonably cost-effective way to access high quality, nutritious animal foods. Ask your local butcher or grocery store which of their animal foods are raised in the most ethical, healthy ways. It may be helpful to know that some of the most nutritious cuts of meat are often also the least expensive: bone-in/skin-on chicken thighs, chicken wings/legs, pork butt and pork shoulder, whole chickens, liver and organ meats of all kinds, full-fat ground beef or ground pork, and dark ground turkey meat are good examples. If you live on a coast, consider highly nutritious and affordable fresh shellfish such as mussels and clams.

Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. If you can’t afford or consistently access best choices, know that eating conventionally raised animal foods is still far healthier for you than eating processed and sweetened foods. Eggs, canned tuna/sardines/mackerel, rotisserie chicken, and even many simple deli meats are good options when you’re too busy to cook or on the run.

You can learn more about how to choose and support sustainable animal foods by visiting the Ethical Omnivore resources page.

Bottom line about meat and health:

- Healthy animal foods are wholesome and nutritionally complete.

- Meat is easy to digest and absorb, and contains no anti-nutrients or irritating substances.

- There is no evidence that meat, saturated fat, or cholesterol are harmful to human health. In fact, there is plenty of evidence that meat, saturated fat and cholesterol are vital to health.

- Whenever possible, choose healthy meats from naturally-raised animals.

- Limit processed meats.

- When eating grilled meats, you may want to trim away any burned or blackened edges.

Check out this all-meat cookbook!

Jessica Haggard recently (2019) published The Carnivore Cookbook. She has created many tasty recipes, and includes good tips for finding affordable meat and how best to prepare different cuts. There is also an entire chapter on offal (organ meats).

Jessica Haggard recently (2019) published The Carnivore Cookbook. She has created many tasty recipes, and includes good tips for finding affordable meat and how best to prepare different cuts. There is also an entire chapter on offal (organ meats).

You may also want to check out my conversation with Tristan Haggard on his Primal Edge Health podcast about the benefits of eating meat for mental health. It is available both in audio and video format.

References Practice and Contact Information

Alaejos MS, González V, Afonso AM. Exposure to heterocyclic aromatic amines from the consumption of cooked red meat and its effect on human cancer risk: a review. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2008;25(1):2-24.

Alexander D, Morimoto LM, Mink PJ, Cushing CA. A review and meta-analysis of red and processed meat consumption and breast cancer. Nutr Res Rev 2010;23(2):349-365.

Alexander DD, Cushing CA. Red meat and colorectal cancer: a critical summary of prospective epidemiological studies. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e472-e493.

Brenner BM, Meyer TW, Hostetter TH. Dietary protein intake and the progressive nature of kidney disease: the role of hemodynamically mediated glomerular injury in the pathogenesis of progressive glomerular sclerosis in aging, renal ablation, and intrinsic renal disease. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(11):652-659.

Cheng K-W et al. Heterocyclic amines. Nutr Food Res. 2006;50:1150–1170.

Fleming RE, Ponka P. Iron overload in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(4):348-359.

Friedman AN, Ogden LG, Foster GD et al. Comparative effects of low-carbohydrate high-protein versus low-fat diets on the kidney. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Jul;7(7):1103-1111.

Geissler C, Singh M. Iron, meat and health. Nutrients 2011;3(3):283-316.

Halton TL, Willett WC, Liu S et al. Low-carbohydrate-diet score and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):1991-2002.

Hodgson JM, Burke V, Beilin LJ, Puddey IB. Partial substitution of carbohydrate intake with protein from lean red meat lowers blood pressure in hypertensive persons. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83(4):780-787.

Hord NG, Tang Y, Bryan NS. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(1):1-10.

Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled dietary modification trial. JAMA 2006;295(6):655-666.

Knight EL, Stampfer MJ, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Curhan GC. The impact of protein intake on renal function decline in women with normal renal function or mild renal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(6):460-467.

McAfee AJ, McSorley EM, Cuskelly GJ et al. Red meat from animals offered a grass diet increases plasma and platelet n-3 PUFA in healthy consumers. Br J Nutr. 2011;105(1):80-89.

McColl KE. When saliva meets acid: chemical warfare at the oesophagogastric junction. Gut. 2005;54(1):1-3.

McClellan WS and DuBois EF. Prolonged meat diets with a study of kidney function and ketosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1930:87:651-668.

Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS. A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):659-669.

Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2271-2283.

Muñoz M, García-Erce JA, Remacha ÁF. Disorders of iron metabolism. Part II: iron deficiency and iron overload. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(4):287-296.

Odermatt A. The Western-style diet: a major risk factor for impaired kidney function and chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301(5):F919-F931.

Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM et al. Red meat consumption and mortality: results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):555-563.

Phillips DH. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the diet. Mutat Res. 1999;443(1-2):139–147.

Ponte PL, Prates JA, Crespo JP, et al. Restricting the intake of a cereal-based feed in free-range-pastured poultry: effects on performance and meat quality. Poult Sci. 2008;87(10):2032-2042.

Siddique A, Kowdley KV. Review article: the iron overload syndromes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(8):876-893.

Willett WC. The great fat debate: total fat and health. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(5):660-662.