As technology has grown more sophisticated, algorithms have slowly crept into more and more operations on college campuses.

Take admissions, where some colleges are using artificial intelligence to help them decide whether to admit a student. While that practice is still somewhat rare, four-year institutions are more commonly using algorithms to help with another admissions decision — how much aid to offer already admitted students.

If an institution has limited resources, education experts say, an algorithm can help optimize how aid is distributed. Others say the practice could cause issues for students and even open institutions up to potential legal risk.

But both skeptics and proponents agree that using an algorithm successfully — and fairly — depends on institutions and vendors being thoughtful.

What is an enrollment algorithm?

Enrollment management and aid algorithms are essentially tools that predict the likelihood that a student will enroll in an institution after being offered admission. But admissions teams can also move the needle on that likelihood — by doing things like offering scholarships and other aid packages.

“The concept is to award financial aid in a way that results in the maximum total amount of net tuition revenue for the institution,” said Nathan Mueller, principal at EAB, an education consulting firm, and architect of the company’s financial aid optimization work.

Enrollment goes up as institutions offer more scholarship aid, but revenue per student decreases.

“What we’re helping them find is the place in between, where they’re giving the best mix of institutional financial aid to raise enrollment to the point where if they gave one more dollar, even though they would increase enrollment, they would start losing that institutional revenue,” Mueller said.

At the individual college level, that process means determining an admitted student’s likelihood of attending and how sensitive they will be to changes in price.

The inputs for each algorithm can differ, depending on an institution’s goals.

Algorithms can, for example, take into account applicant information, such as grades, test scores, location and financial data. Or they may also look at an applicant’s demonstrated interest in a college — whether they have visited campus, interacted with an admissions officer or answered optional essay prompts.

EAB counsels its own clients to not use those interest markers in aid determinations.

“We do look at some of those things, as ways of understanding how engaged a student is and understanding their price sensitivity,” Mueller said. “It absolutely has predictive value, but from our vantage point it crosses into the area of something that’s really not an appropriate mechanism to determine how much aid a student receives.”

In the past, Mueller said, many colleges committed to cover 100% of a student’s demonstrated need. But in the early ‘90s, Congress changed how need analyses were conducted — making many families appear needier — and reduced funding for Pell Grants. As a result, fewer colleges believed they could afford to make that pledge, he said.

While some institutions do not use algorithms to help determine aid, their goals are often similar to those that do, Mueller said. Today EAB works with about 200 clients — most of them private colleges — on financial aid optimization.

Careful consideration

Vendors emphasize that the algorithms they offer aren’t just mathematical models that run and spit out a result to be followed exactly. They allow an admissions team to try out different aid strategies and see how those might change things like the diversity, gender balance and academic profile of their incoming class.

“The criticisms about algorithms or about artificial intelligence specifically have been around this idea that they are sort of running loose on their own and don’t have overriding guardrails that reference institutional philosophies or strategic goals,” Mueller said. “We would never want anyone to just follow a mathematical exercise without any consideration of the other key strategic aspects.”

But Alex Engler, a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution said he’s skeptical about whether institutions are appropriately contemplating how they’re using these tools.

Because algorithms are frequently trained on data resulting from human decision-making, they often show evidence of human bias and lead to different outcomes for different subgroups.

In financial aid, that could be consequential. Engler said he’s unsure that the college officials working with algorithms day to day have the technology and data expertise to feel confident challenging the algorithms.

“Sometimes universities aren’t or can’t sufficiently evaluate and adjust the algorithms and really be self-critical in their impacts,” he said.

For instance, some students may choose to enroll in a college if given certain aid packages — even if it’s not the best financial choice for them. And students who are burdened with high costs are unlikely to persist and graduate, leading to poor outcomes for both them and their colleges.

“Sometimes universities aren’t or can’t sufficiently evaluate and adjust the algorithms and really be self-critical in their impacts.”

Alex Engler

Senior fellow, The Brookings Institution

Wes Butterfield is senior vice president of enrollment at Ruffalo Noel Levitz, an educational consultancy firm that also offers aid products to colleges. He said algorithms and aid strategies can take persistence and graduation into account.

“What the campus is trying to figure out is, how do I provide a fair amount of aid that will allow a student not only to enroll, but I think more and more campuses are also thinking about that retention piece, what is the proper amount of aid to allow a student to walk across a stage,” Butterfield said.

Ideally, he said, he would like to see similar aid packages offered across institutions.

“Students should be enrolling because of mission fit, because of the major, because they like the extracurricular activities,” Butterfield said. “I’m trying to neutralize aid as a factor.”

Human touch

Legally speaking, these algorithms don’t require human touch. In the European Union, citizens have the right to have a human being review decisions of major consequence, like the terms of a loan.

But that right doesn’t exist in the U.S., said Salil Mehra, a law professor at Temple University. Mehra said that misuse of aid algorithms could potentially open institutions up to antitrust liability.

In August, the University of Chicago settled an antitrust suit alleging 17 universities of price-fixing by illegally colluding on their financial aid policies.

But Mehra said it’s also theoretically possible for institutions to collude without express intent, such as by using the same consultants who are then using very similar formulas with each client.

“It might, as a result, have a similar effect as an explicit agreement in reducing the amount of financial aid that students with need would receive,” Mehra said. “That’s actually potentially scary or concerning because it would be difficult to discover if that was happening.”

In general, higher education is facing legal scrutiny that didn’t exist before the 2019 Varsity Blues scandal, in which wealthy parents paid to have their children gain entry to top-ranked colleges. Colleges would be wise to stay abreast of ways they might be exposing themselves to antitrust liability, Mehra said.

Mueller, from EAB, said the company’s algorithms are unique to every institution.

“Ultimately there are substantial differences in the model used for each college, and where the factors are similar, they’re driven by the competitive environment, not an inherent sameness in the models,” he said via email.

A complex tool

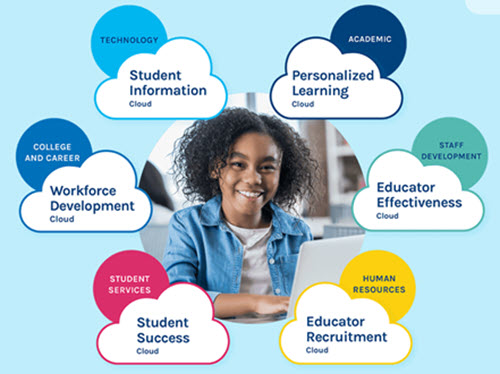

In practical use, colleges and admissions offices may not see aid algorithms as a standalone piece of technology but rather as a more comprehensive tool for understanding their probable yield.

The company Othot, which offers analytics and AI products to colleges, published the results New Jersey Institute of Technology realized from its algorithmic tools. In fall 2018, when NJIT began using the technology, the college enrolled 173 more first-year students and saw net revenue increase.

But officials at NJIT say they don’t think of the technology as specifically an aid tool but as one that predicts yield, helping them ration limited resources. That includes aid, but also time and effort from admissions staff. The technology doesn’t make decisions on its own, they note.

“It’s not telling us what to do,” said Susan Gross, vice provost for enrollment management.

Engler, at Brookings, recommends that colleges and admissions offices hire people with data expertise to work with any algorithms, while also paying close attention to how their admissions strategy is performing over time and how students are faring after they are admitted.

“There’s a lot that can be done to improve practices,” he said, “and make sure that you’re going to have such an algorithm system where there are at least some checks for, ‘Well hey, are we systematically disadvantaging or undermining our own students?’”

Lilah Burke

Source link