Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Local News

The Yuppification of Philadelphia

[ad_1]

How young urban professionals of the 1980s reinvented Philly — and America.

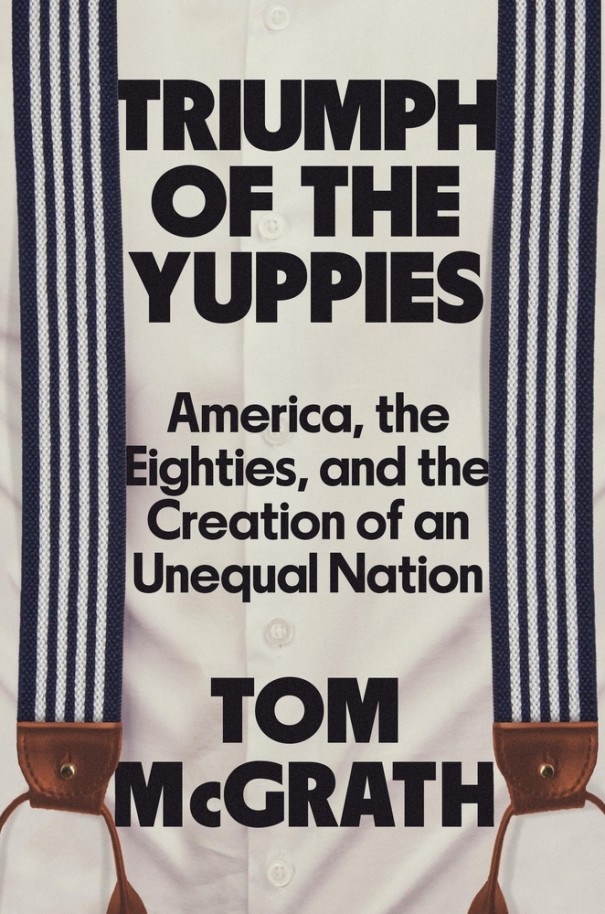

Former Philly Mag editor Tom McGrath releases his book, Triumph of the Yuppies: America, the Eighties, and the Creation of an Unequal Nation, on June 4th./ Book jacket art courtesy of Hachette Book Group; Photograph of Tom McGrath by Jeff Fusco

Like any big city, Philadelphia has been shaped by many factors through the years. Among the most significant? The impact of sophisticated, well-educated “young urban professionals” of the late 1970s and early 1980s — a.k.a. much-buzzed about (and eventually much-loathed) Yuppies.

It was Yuppies who played a role in bringing a new energy to Center City (and elevating our restaurant scene), while also gentrifying certain Philly neighborhoods and collectively contributing to a broadening of the educational and economic divide.

In an excerpt from his new book, Triumph of the Yuppies: America, the Eighties, and the Creation of an Unequal Nation, former Philly Mag editor Tom McGrath details how a cadre of college-educated Baby Boomers began putting their stamp on the city, and how Philadelphia played a vital role in creating the broader 1980s Yuppie phenomenon.

Triumph of the Yuppies

In the summer of 1980, as Ronald Reagan readied himself to accept the Republican nomination for president, a new restaurant was opening in Center City. Actually, Frog, as it was called, wasn’t really new new. The original version of the restaurant had opened seven years earlier in a tiny storefront space around the corner, the creation of an affable young Penn grad named Steve Poses. That Frog was a funky, offbeat place with mismatched furniture, lots of potted ferns, and an overabundance of frog decorations — the kind of relaxed space where Poses had imagined his friends from college might hang out and discuss the issues of the day.

But something extraordinary happened at the original Frog: It had become, very quickly, a mini sensation. Poses’s friends did come, and so did a lot of people just like them, and then so did a lot of other curious Philadelphians. They were attracted by the buzz, but also by Frog’s vibe — so different from the fine dining restaurants in Philadelphia — and by its food: a mix of dishes that took traditional French cuisine, lightened it, then mixed in Asian and American influences. Poses himself wrote the menu on a blackboard twice a day — once for lunch, then again for dinner. Eventually, he decided he could afford two blackboards.

The original Frog was such a hit that Poses was emboldened to expand his operation. In 1977, he launched what was essentially a modern gourmet cafeteria a few blocks away — a place called the Commissary that opened early in the morning and didn’t close until late and was unlike anything Philly had ever seen. The Commissary was an even bigger hit than Frog, and Poses kept going. He launched a catering operation, then a gourmet market attached to the Commissary, then another upscale cafeteria across town called Eden. Now, finally, he’d decided it was time to redo his original creation, Frog. His customers weren’t grad students anymore, and they were ready for something more grown‐up. And so he was moving Frog into an elegant town house on Locust Street, confident loyal Frogsters would be happy to move with him.

Poses, a soft‐spoken, humble guy who turned thirty‐four in 1980, hadn’t really planned any of this. He’d grown up in Yonkers, New York, before enrolling at Penn in the fall of 1964. His original plan was to study architecture, but by the time he graduated, in 1968, the world had changed completely, and Poses had changed with it. He’d gotten deeply interested in social issues, opposing the war in Vietnam, and ending up with a degree in sociology. Afterward, he landed a draft‐deferring job working at a school for learning disabled kids and pondered what he might do with his life. That’s when he focused on restaurants. He’d developed an interest in cooking during college, and so he quit the school after a couple of years and started working as a busboy at one of Philadelphia’s most proper French restaurants. His job was hardly glamorous, but it taught him the business, and in 1973 he opened the original Frog, putting an emphasis, as he’d later say, on “food and community, those two things meshing.”

Now, seven years later, Poses was unexpectedly running an operation with several hundred employees and millions in revenue. Perhaps even more importantly: He and the young professionals who frequented his restaurants were injecting a small dose of modern energy into Philadelphia’s struggling downtown. As one observer put it, thanks to Poses, “Suddenly, there were places to eat in Philadelphia other than Arthur’s Steak House and Bookbinders.”

Poses was focused on Philadelphia, but by 1980 similar pockets of energy were popping up all around the country. Boston. San Francisco. Chicago. Washington, DC. New York. Over the previous half dozen years, a small influx of young professionals had been quietly settling in working‐class neighborhoods in all those cities. Their numbers were tiny, but the presence of the new group — the vast majority of them white and well‐educated — had become increasingly noticeable.

The arrival of this young professional class cut against the grain of what had been happening in American cities over the previous quarter century. Indeed, among the few losers in America’s great postwar period of power and prosperity had been the country’s urban areas. The population numbers told the sad tale. Between 1950 and 1980, Philadelphia’s population dropped from 2.0 million to 1.7 million; Chicago’s from 3.6 million to 3.0 million.

So why, now, was a small, elite slice of a new generation reversing the migration and moving back into cities? Cost was part of the answer. You could get a deal in the city — once‐stately old homes with great bones were selling for $30,000, sometimes even less. Even more powerful, though, was what living in the city said about your identity: You were cosmopolitan. You were sophisticated. You were not, above all, your conformist, suburban‐dwelling parents.

Robin Palley set down roots in the city during the 1970s, and in many ways her story was typical of the Boomers embracing urban life. Palley had grown up in a middle‐class family in the Shore town of Margate in the ’50s and ’60s, a period, as she’d later put it, “where your shoes and your bag had to match. Everything was about measuring yourself with a financial yardstick and how well you fit in.”

As with others of her generation, Palley’s worldview had begun to change when she went off to college — in her case, to Penn in the fall of 1968. Early in her time there, Palley walked onto the campus’s main quad and saw it filled with small white crosses, each representing a life lost in Vietnam, and it had spurred her to protest alongside her classmates and friends. But opposing the war was only the beginning of her political awakening. The mood on campus was about breaking free from conformity and embracing your individuality — although, as Palley would later come to note wryly, she and her friends all expressed that individuality in precisely the same way: with long hair and blue jeans.

Palley graduated in 1972 and left Philadelphia for Paris, where she ran a bookstore for a couple of years. When she returned to Philadelphia, she and her young husband were certain of one thing: They would not live in the suburbs. “I came back and did not want to go back to that suburban life and fitting into that straitjacket of being,” she said later. “I wanted to live my ideals, which had to do with equality and being around all kinds of people.”

The couple ended up buying a house in Fairmount. Actually, it was really more of a shell of a house — most of the innards had been stripped away, opportunistic vandals had even stolen the crossbeams. But the young couple loved the working‐ class, mostly Puerto Rican neighborhood they’d be moving into, and they were excited about the vitality of city life. They bought the place for $9000 and got to work fixing it up.

By the late ’70s the phenomenon of young professionals situating themselves in cities was widespread enough that it had earned a name: the “Back to the City” movement. Reporters started writing occasional pieces about what was happening, and curious academics decided the phenomenon, while still nascent, was worthy of study.

In 1977, the Parkman Center for Urban Affairs in Boston hosted a conference that brought scholars and policy wonks together with a group of young Boston professionals. (The Parkman folks also fanned out around the country to interview even more city-loving young professionals.)

What was perhaps most interesting about the group of young city dwellers was their own view of themselves. “I’d say we were more concerned about intellectual things,” a conference attendee who lived in Boston’s Back Bay said. “We want to have seen the latest films. We want to know what people are reading.”

Said a New Yorker: “I want a racially and socially mixed neighborhood….I don’t want to live with a collection of people who are just like I am professionally and socially.” Perhaps the most telling comment came from a young St. Louis woman, who said simply, “We’re more interesting.”

The remarks certainly caught the attention of the Parkman team. “Whether the young professional emphasizes intellect…or living style…or a Thoreauesque standing apart from convention, there are very often feelings of superiority toward his or her suburban counterparts,” they noted in their report. “In this sense, at least for the duration of their time in the core city, young professionals identify themselves as part of an elite within the middle class elite.”

What also stood out to conference organizers was the power and status of this new group, and their potential to help reinvigorate cities more broadly. They were educated, they were increasingly affluent, and they were on the leading edge of the culture, all of which made them influential.

And in fact, by the summer of 1980, their influence was already spreading, their numbers already expanding. As Robin Palley would note, once again wryly, about her own decision to live in the city, “Just like with blue jeans, I got the idea at the same time tens of thousands of other people did.”

•

By the beginning of the 1983, the number of young professionals flooding into cities across America was continuing to increase, and the media was beginning to pay attention. It wasn’t just where this new group lived that was notable — it was how they lived, with a focus on money and a keen interest in success in every aspect of their lives.

In Philadelphia, a twenty‐seven‐year‐old writer named Cathy Crimmins was among those noticing. One detail that kept popping out was the way people her age were starting to talk. Suddenly, phrases like “interface,” “pencil you in,” “bottom line,” and “prioritize” were showing up in people’s everyday conversations. It was as if a new species had been born, she thought, one that couldn’t distinguish between their jobs and the rest of their lives.

Crimmins had one foot inside and one foot outside this blossoming, hyper‐professional world. She’d grown up in suburban New Jersey in the late ’50s and ’60s before going to an all‐women’s liberal arts school, Douglass College. She’d missed the anti‐war movement by a few years, but the countercultural vibes were still strong enough for her to not get too caught up in thinking about work or a career. She’d “taught macrame and hung around with potters,” as she’d later put it, for a few years before enrolling in a graduate program in medieval literature at Penn. It was there, as she was finishing her degree, that she smacked head‐on into the real world. There were, she realized, maybe five jobs for medievalists in the country, and those jobs were filled. So off she went to earn a living, first writing copy for a seed catalog, then working for a corporate consulting firm.

The more she became immersed in the professional world, the more Crimmins noticed how her friends were changing, how the world was changing, how she herself was changing. People with whom she’d once smoked weed and drunk wine were now wearing pin‐striped suits and carrying slim briefcases and talking about building their “networks.” When her friends called her, it wasn’t to say hello — it was to see if she knew of any good job openings. And the ambition wasn’t limited to their professional lives. Crimmins noticed her friends — and herself, to some degree — working hard to be chic and cosmopolitan when it came to the food they ate and the clothes they wore and how they decorated their homes. Everybody, a friend observed to her, suddenly seemed to be aspiring. They were aspiring professionals.

Crimmins had done some freelance writing, and she decided she had an article idea on her hands. She came up with her own name for this new business‐obsessed species — young aspiring professionals, “YAPs.” She talked to an editor friend at a new alternative newspaper in town, the City Paper, who recognized the phenomenon she was talking about and gave her the green light to write the piece. Crimmins’s story — titled “The YAP Syndrome” — was published in City Paper in April 1983.

Crimmins hilariously spelled out a phenomenon that was happening not only in Philadelphia, but in cities across the country.

“Typical YAPs are 25 to 40, well‐educated, well‐motivated, well‐dressed and well‐exercised. Fast‐track YAPs eat out regularly, see a hair stylist at least every six weeks, make wise investments, and, with their disposable income, hire people to do things they don’t have time for due to the demands of a hectic career.”

Crimmins pinpointed some of the status details that differentiated the tastes and choices of this burgeoning group — from city townhomes to gourmet food stores to “better baby” flash cards.

“The YAP Syndrome” touched a nerve, generating buzz around Philadelphia when it was published. One of the people who read the story was Larry Teacher, cofounder of the Philly‐based book publisher Running Press. The runaway success of The Official Preppy Handbook three years earlier had publishers looking for ways they could put their own spin on the concept, and with YAPs, Teacher figured he had a winner. Crimmins began working on what amounted to a YAP version of the Preppy Handbook.

YAP: The Official Young Aspiring Professional’s Fast-Track Handbook arrived in bookstores in November. The cover featured an illustration of a young woman in a business suit, carrying a briefcase (stuffed with the Wall Street Journal) and wearing a pair of running shoes. Next to the drawing was a caption:

Why did the YAP cross the road? A. To get to the better side.

Inside, Crimmins followed the formula that had made The Official Preppy Handbook such a hit. The book was divided into multiple sections, each focused on a different area of YAP life, and each containing plenty of sidebars, quizzes, and fun photos and illustrations.

Crimmins delved into the various aspects of YAPness, including the YAP love of “original features” in their town houses; a list of YAP favorite foods (black beans, hummus, pesto, Perrier); the YAPs’ love of gadgets and technology (including answering machines, call waiting, and beepers).

In the late fall, Crimmins began doing press to promote the book. Chatting with a reporter from the Inquirer, she laid out the various tenets of YAPness.

YAPs were Baby Boomers, she explained, which meant they came of age in the 1960s, when individuality was celebrated, and they didn’t like to admit to the conformist tendencies of their parents. “They like to think that eating croissants, buying an historically certified building, or shopping in an old firehouse protects them from conformity,” she cracked.

While YAPs engaged in various types of behavior, Crimmins said, ultimately it wasn’t very complicated.

“All you really need to be a YAP is a good, healthy dose of overachiever’s anxiety,” she said. “Of course, owning a Cuisinart and seeing a good hair stylist doesn’t hurt.”

As luck would have it, the term “YAP” would never really catch on. Just a few months after Crimmins’ book was published, two New York writers published a similar tongue-in-cheek paperback called The Yuppie Handbook. YAPs and Yuppies were basically the same thing, but “Yuppies” is how most of the world would very soon come to know this influential group.

Adapted from Triumph of the Yuppies: America, the Eighties, and the Creation of an Unequal Nation by Tom McGrath, published on June 4, 2024. Copyright © 2024 by Tom McGrath. Used by arrangement with Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

[ad_2]

Tom McGrath

Source link