There are more than 75,000 wild horses roaming public land in the west. “Wild horses” are the descendants of domesticated horses, the first brought here by Spanish explorers 500 years ago. By 1971, their numbers were dwindling and Congress stepped in, passing a law to protect this romantic fragment of our history. it worked almost too well. Today, federal land managers say the number of wild horses is nearly three times what it should be – and left unchecked, their population can double every 5 years. So, when we heard about a program in Wyoming designed to rein in the wild horses – and an unlikely group of men – we headed west.

It’s hard to imagine anything surviving on this stretch of badlands in northern Wyoming. Sagebrush blankets the high desert all the way to the Rocky Mountains. But in this empty quarter of the Cowboy State is a thundering herd of mustangs, untouched, wild and breathtakingly beautiful.

But wild horses can also wreck the rangelands they roam. Government land managers say, in the West, wild horses are competing with cattle and wildlife for increasingly scarce water and food and their overpopulation often further strains the environment.

So the Federal Bureau of Land Management regularly rounds up wild horses. Mainly by using small helicopters to locate, capture and truck them off to corrals or enclosed pastures like this one – a horse can live for about 20 years and most of these horses will remain here until they die.

The Wind River Wild Horse Sanctuary outside Lander, Wyoming, is run by Jess Oldham and his family.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Talk about the horses that are here. For most of them, this is it, right?

Jess Oldham: Yes, ma’am. We have the 225 long-term residents and–

Sharyn Alfonsi: Long-term residents?

Jess Oldham: Long term residents.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Sounds like a nursing home.

Jess Oldham: That’s what I call ’em. I mean they’re part of our family. And– and– they’re gonna be here long term.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And there they go.

Jess Oldham: Yes, ma’am.

The 1,400 acre facility is on an indian reservation. The Oldham’s are one of dozens of contractors paid by the government to feed and care for mustangs after they’ve been removed from the wild. Activists want the horses to remain free.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Why not just let the wild horses be wild and run?

Jess Oldham: The harsh reality is ecosystems are a delicate balance of each species coexisting together in the environment. There is a limited amount of resources in grass and water. And the wild horses are a very dominant species. They’re smart. They’re fast. They eat a lot of food. And they need to be properly managed.

Keeping count of all those horses is Holle Waddell, the division chief of the program that oversees wild horses for the Bureau of Land Management.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How many wild horses is the government now caring for?

Holle Waddell: So we are currently caring for over 57,000 wild horses.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And caring for them is not inexpensive.

Holle Waddell: No. The cost of care for wild horses in our off-range corrals and pastures was two-thirds of our budget last year, which was a little over $70 million.

Sharyn Alfonsi: $70 million to care for the wild horses.

Holle Waddell: Taxpayer dollars.

To relieve some of the burden on taxpayers, last year, the Bureau says 3,742 mustangs came off the government rolls through an incentive program that pays individuals a thousand dollars to adopt one. Wild horses attract relatively few takers, but these horses did. Picked for their youth, balance, and temperament – they are sent to be trained in, of all places, prisons like the Wyoming Honor Farm.

It’s a 640-acre compound of tidy buildings, manicured lawns, cattle and enough hay to feed them. It may look like a dude ranch, but this is a state-run, minimum-security prison with felons working the land and the horses. There are no towers or armed guards – a simple four-foot cattle fence marks the perimeter between the prison and the town of Riverton, Wyoming.

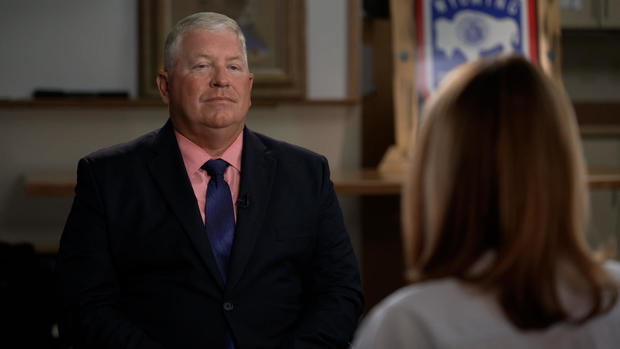

Curtis Moffat: Yeah, Wyoming has a tendency to do things a little differently cause we’re a smaller state. And I think it’s one of those things…until you see it you can’t actually believe it yourself.

Curtis Moffat has spent his entire career in corrections. He’s the warden on the farm and about the only one here who doesn’t wear cowboy boots to work.

Sharyn Alfonsi: The thing that struck me when you drive up you see a four-foot– high cattle fence. What’s to stop an inmate from making a run for it or riding off into the sunset?

Curtis Moffat: Realistically, himself. Most of these guys are at the end of their sentence. So most of ’em don’t want to destroy that or, you know, catch another number– do another five years or so. It’s on them to make sure that they’re gonna do things the right way.

Most inmates have earned the right to be here, transferred for good behavior from more restrictive state prisons. And each day about 30 inmates report to work in a maze of chutes and pens with wild horses weighing up to 1,000 pounds – their job is to transform these mustangs from wild burdens of the state into riding horses that can fetch thousands at auction.

Travis Shoopman: These guys are here to do their time. But it’s really about changing their life, put a change in them in a positive direction.

Travis Shoopman is the cowboy in charge. He’s the manager of the farm.

Shoopman spent his life teaching the art of training horses. It shows in a stride kinked by old fractures.

Travis Shoopman: Have you ever had a halter on this horse Mr. Suchor?

Peytonn Suchor: Never.

And a voice both firm and calm – as much for the inmates as the horses.

Travis Shoopman: Do the rope-a-dope and throw the rope into your hand. Do not get kicked.

It takes time to train a wild horse, but Shoopman says there’s nothing special about how it starts.

Travis Shoopman: You walk him in there, like you just kinda rip off the Band-Aid and the human goes in there.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What’s the next step?

Travis Shoopman: Then you teach ’em to yield to pressure. So, you stop the forward movement, teach ’em that if they move forward towards you the pressure goes away. And then from there you get to where you can touch ’em, you get to where you can pet ’em, introduce a halter, get ’em halter broke. And then you have that trust. Like, they understand if they give up their right of flight to stay with you, there’s some trust there.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Are you talking about the horses or the inmates?

Travis Shoopman: The horses. We are in the people business and helping the horses is extra. But the guys really learn a lot of life lessons from the horses. They learn to try, they learn to not lie to themselves about their feelings, they learn to control whether it’s the highest of high emotions or the lowest of low emotions.

No one here ‘breaks’ a horse – the method used at the farm is called ‘gentling’ – force is replaced by patience, persistence, and an even keel. In any pen on any day, you can see it play out. A ballet in dusty boots. A delicate dance of inches, repeated a hundred times over. Days in the making, for this, the first human touch. Next door, a mustang in full gallop, a runaway train, yields and stops on command.

Sharyn Alfonsi: We’re watching all these things step, by step, by step, but this doesn’t happen overnight.

Travis Shoopman: No. Sometimes it’ll take four weeks. Sometimes it’ll take four months to do these steps. And a wild horse takes a little bit longer sometimes.

Michael Davis has been riding horses his whole life. He’s serving 15 to 20 years for voluntary manslaughter – he’s eligible for parole in a little over three years.

Michael Davis: If you’re mad, if you’re scared, that horse knows before you ever even touch it. How they know, I don’t. You have to control your feelings considerably with the horse because it is so easy for them to pick up on your mood.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So you’re good at controlling your feelings with the horse. But with people, how are you doing?

Michael Davis: Not real great.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You’re still working on that?

Michael Davis: I have my moments. I’m still workin’ on it. But we’re gettin’ better.

Davis is an old cowboy and one of only a few inmates here who can handle this – this horse has never had a man on its back, until now. A remarkable skill that can’t be acquired without a few scars.

Michael Davis: I’ve got broken ankle, a separated shoulder, a broken collarbone, stitches in my head, broken hand. Fingers, lots of fingers.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What has the program taught you? What’s it meant to you?

Michael Davis: A little piece of freedom. I mean, I’m wearin’ boots and jeans instead of hospital scrubs. And, I mean, it’s hot out here, but it’s a good hot. It’s as close to bein’ outside as I can get until I get outside.

Out here it is easy to forget this is a prison with 300 inmates under the watchful eye of Warden Moffat.

Sharyn Alfonsi: People at home will say like these guys are felons. They’ve done terrible things. Committed awful crimes, ruined families. Why should they be allowed to be out here, to be trusted to be working with these horses?

Curtis Moffat: We don’t provide the sentence to ’em. We don’t provide the punishment for ’em. The judge decided all of that. Our job is to supervise ’em while they’re in here. And hopefully return ’em to society where they’re responsible individuals, where they can be law-abiding citizens. I think this program goes a long way to do that. And I want to make sure they get out and– and we can believe that they’re gonna be successful. And they aren’t gonna re-offend.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You want to make sure, right, that the horses aren’t returned, and the inmates don’t return? Is that fair to say?

Curtis Moffat: Right. Right. Right.

In Wyoming, the recidivism rate is below 30% and if you’re wondering about that 4-foot cattle fence, well, the warden says, in the last 22 years, fewer than 10 inmates have made a run for it.

Staying on the right of the fence is not lost on Peytonn Suchor, an inmate serving 7 to 10 years for aggravated assault. He transferred from a maximum-security prison a year ago and came here with no experience working with horses.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What’s it like to step into a pen the first time with a wild 800-pound horse?

Peytonn Suchor: Adrenaline, heart-pounding excitement. But I was excited to do it ’cause once you get a horse to go the direction you want and then come join up to you and you turn around and he’s right there. It’s like wow. This animal, this connection, this feeling. I can’t explain it.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What has this taught you about yourself?

Peytonn Suchor: It’s taught me responsibility. It’s taught me what I wanna do for a career when I get outta here. This makes you look at life a whole different way.

And Suchor’s patience and feel are paying off. At auction, a gelding like this one could sell for thousands – but it’s not without a little heartache.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Is it hard to see them go?

Peytonn Suchor: It is but at the same time we’re not doin’ this just for us, we’re doin’ it for them, too. It’s a second chance for them, as well.

This September, the Honor Farm held its second auction of the year. Hundreds of buyers came to the prison from all over the country to inspect these horses and query their trainers – a little like kicking the tires on a car lot. Then, each mustang takes the main stage, trotting and loping – sold to the highest bidder. In all, 34 horses fetched $65,000 for the Bureau of Land Management, an achievement almost as good as the look on the inmates’ faces.

But remember Michael Davis, the old cowboy who couldn’t be bucked? We noticed he wasn’t at the auction. The warden told us he was suspended for not getting along with others. Gentling a horse and rehabilitating the man don’t always happen on the same clock. By high noon – every mustang had a new home and for this wild bunch, gentling has its virtues.

Sharyn Alfonsi: I think I know the answer to this. If you were a betting man, would you bet a psychologist is quicker to change the behavior of man, a doctor, a therapist, or a horse?

Travis Shoopman: I think a horse. 100%. And that’s just purely Travis Shoopman talking, but the horses are a major role in what betters those men. They can teach you life lessons every step of every way. Teach you that you got something in you that you didn’t think you had. They can teach you that it’s okay to be afraid, but it can still be done. Nothing’s impossible. There’s so many life lessons.

Produced by Michael Karzis and Katie Kerbstat. Broadcast associate, Elizabeth Germino. Edited by Warren Lustig.