Home & Garden

The Book of Wilding: A Practical Guide to Rewilding Big and Small: Review

[ad_1]

The rewilding project at Knepp, a farming estate in Sussex, England, has been well-documented, first with c0-owner Isabella Tree’s best-selling eco-memoir, Wilding—and now with her new book, The Book of Wilding: A Practical Guide to Rewilding Big and Small. Written with her husband Charlie Burrell, whose family bequeathed him an infertile and unprofitable farm 11 years ago, it is a rewilding manual for serious enquirers, a preparation-results-conclusion guide to achieving a phenomenal surge in biodiversity on anyone’s land.

Rewilding has been interpreted as permission to let go, to let weeds trip people up as they navigate city streets, or to sit back and watch the most vigorous plants take over our once-tended green spaces. “Time to End the Rewilding Menace,” Julie Burchill argued in the Spectator a few weeks ago, while the British press created a storm over comments from gardeners Monty Don and Alan Titchmarsh (who respectively called it “puritanical nonsense” and “an ill-considered trend”). Anyone with a vested interest in garden design is against rewilding, we are led to believe.

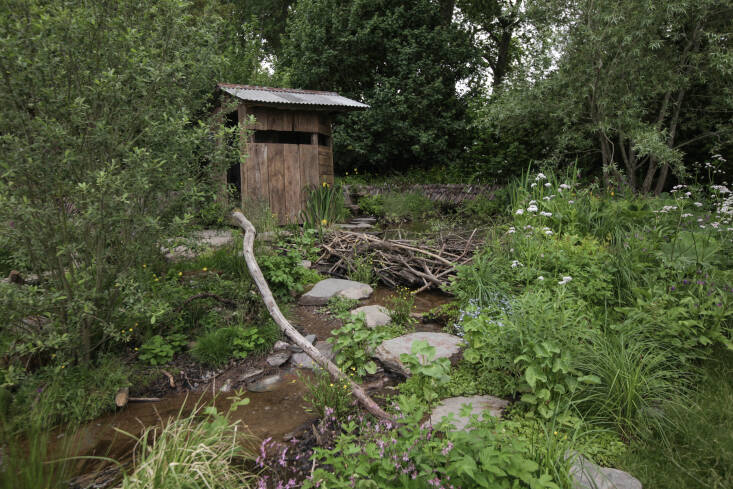

But there is a distinction between wilding and rewilding, arguably. Rewilding a large tract of land involves healing a landscape and reintroducing missing fauna and mega-fauna (or at least mimicking their activity in the interim) as a step towards restoring ecological function. Wilding a garden on the other hand is beautifully attainable for all; a wilded flower pot, tree pit, stoop, or balcony may sound silly, but it really just means being guided by nature when planting, rather than relying on received ideas.

Photography by Jim Powell, except where noted.

The subject of wilding and rewilding is complicated, as reflected in the book’s size (560 pages). For speed readers, it is absurdly easy to mock. In the chapter “Becoming the Herbivore,” we are directed to replicate a “pig nest,” the rootling disturbance of wild boar, a “stallion latrine” (introducing dung to encourage nettles). For anyone coming to grips with just mowing their lawns less frequently, it can be disquieting when a gardener says, “You are the bison.” What they are trying to tell you is that in the absence of keystone species—roaming herbivores—it is up to us to create optimal conditions for biodiversity with our own periodic disturbance: roughing up terrain and making inviting pockets for habitat, spreading seeds as an animal would in their hooves and fur, interrupting the impulse of trees to grow up into a closed canopy forest. Anybody with a serious amount of land can leave this to wild ponies, elk, and rare breed pigs.

[ad_2]