Bazaar News

The Astonishing Story Of The Venus de Milo, The Iconic Statue That Was Accidentally Discovered By A Farmer

[ad_1]

From its accidental discovery on a Greek island in 1820 to its missing parts to its relocation from the Louvre during World War II, the Venus de Milo has had a dramatic history.

picturelibrary/Alamy Stock PhotoThe Venus de Milo sculpture inside the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Despite being incomplete, the Venus de Milo is one of the most famous art pieces of all time. This iconic armless sculpture dates back to the Hellenistic Period of ancient Greece, about 2,200 years ago, on the island of Melos.

Rediscovered in 1820, the sculpture was an immediate sensation when it arrived at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France, celebrated as much for its imperfections as for its exquisite craftsmanship. And the Venus de Milo’s turbulent history is just as fascinating as the sculpture itself.

The History Of The Venus De Milo

In 1820, French Navy officer Olivier Voutier sailed to Melos, a Greek island in the Aegean Sea that at the time was under Ottoman rule. An amateur archaeologist, Voutier had come to the island in search of ancient Greek antiques — and stumbled upon the discovery of a lifetime.

On April 8, 1820, a farmer named Yorgos Kentrotas was rummaging for stones in the ruins of an ancient city on the island when he uncovered a fragmented marble statue of a half-naked woman. Voutier, who had been searching for antiquities nearby, came upon the scene and was amazed at the discovery.

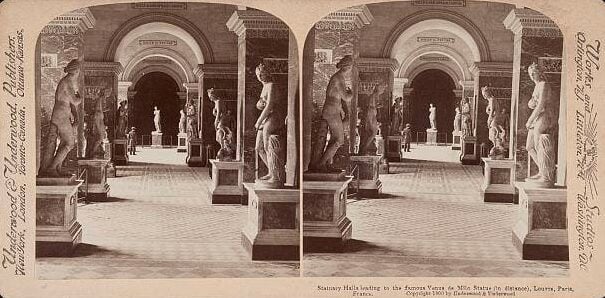

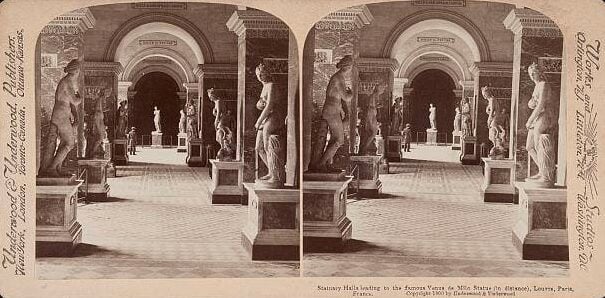

Library of CongressThe Statuary Hall leading to the Venus de Milo in the Louvre Museum. C. 1900.

Convinced of its authenticity, Voutier contacted the Comte de Marcellus, secretary to the French ambassador to the Ottoman Turks. Together, the two men organized the sale of the statue, ultimately paying 250 francs to local officials and another 750 to Kentrotas.

In February 1821, the Venus de Milo arrived in Paris, where it was delivered to King Louis XVIII as a gift. Soon after, the king donated the sculpture to the Louvre.

The museum’s director, the Count de Forbin, was ecstatic about the find. Initially, Forbin believed that the sculpture dated to Greece’s Classical period (c. 510 to 323 B.C.E.). However, that wasn’t the case.

Researchers soon determined that a base found with the Venus de Milo bore an inscription that read “Alexandros, son of Menides, citizen of Antioch of Maeander made the statue.” Very little was known about Alexandros of Antioch, the sculpture’s creator. However, Antioch was not founded until about 280 B.C.E., meaning the statue likely dated to the Hellenistic era.

Disappointed that the Venus de Milo did not belong to the more respected Classical period, the Louvre paid scholars to publish writings asserting that the sculpture had come from the school of the Classical artist Praxiteles — a lie that the museum maintained for over 130 years, according to Smithsonian.

In the years since, the inscribed base has gone missing, only adding to the mystery surrounding the enigmatic sculpture.

The Venus De Milo’s Missing Pieces

Chosovi/Wikimedia CommonsThe Venus de Milo was created by the artist Alexandros of Antioch.

Standing an imposing six feet and eight inches tall, the Venus de Milo was crafted from marble, probably sometime in the 2nd century B.C.E.

In its heyday, the statue would likely have been vibrantly painted, though the colors have faded over time. The statue also shows signs that it was once adorned with jewelry, including an armband, earrings, and a headband.

The sculpture’s arms were missing when it was discovered, leaving its original form a mystery. However, Gregory Curtis writes in his 2003 book Disarmed: The Story Of The Venus de Milo that Yorgos Kentrotas, the farmer who found the Venus, later uncovered additional pieces, including a marble hand holding an apple, a section of a badly damaged arm, and quadrangular pillars with a carved head on the top.

Public domain/Wikimedia CommonsAn imagined reconstruction of the Venus de Milo by Adolf Furtwängler. 1893.

To this day, experts are still unsure who the statue was meant to depict. Many scholars believe she represents Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and fertility. If that is the case, the apple could be a reference to “the Judgement of Paris,” a story from Greek mythology in which Paris, the prince of Troy, gives Aphrodite a golden apple.

However, the people of ancient Melos particularly revered Amphitrite, the wife of Poseidon. It’s possible that the statue was in fact meant to honor the sea goddess rather than Aphrodite.

The Evacuation Of The Louvre

For decades, the Venus de Milo stood in the Louvre, enthralling generations of audiences and steadily becoming one of history’s most celebrated sculptures.

But in 1939, the threat of World War II was swiftly making its way to Paris. Desperate to preserve its rich collection, the Louvre’s curators devised a plan to hide the Venus de Milo and other valuable art pieces from pillaging Nazis.

Thus began a massive operation to evacuate the Louvre. On Aug. 25, 1939, officials closed the museum for “renovations” as workers began covertly packing thousands of its most prized and fragile works into wooden crates and loading them into trucks. Convoys of about 200 trucks transported the pieces to various safe locations throughout France, including palaces, abbeys, and museums.

The Venus de Milo was shipped to the Château de Valençay in central France. According to TheCollector, the museum even replaced the sculpture with a plaster replica, which greeted the Nazis when they arrived in 1940.

French Ministry of CultureWorkers transporting the Venus de Milo as part of the evacuation of the Louvre.

Because of these efforts, the Venus de Milo lived to see another day. Paris was liberated in 1944, and after the war finally ended, the Venus de Milo returned to the Louvre.

Today, the statue remains one of the Louvre’s most cherished artifacts, all the more beloved for her imperfections.

“The Venus de Milo is an accidental surrealist masterpiece,” art critic Jonathan Jones wrote for The Guardian in 2015. “Her lack of arms makes her strange and dreamlike. She is perfect but imperfect, beautiful but broken — the body as a ruin. That sense of enigmatic incompleteness has transformed an ancient work of art into a modern one.”

After reading about the Venus de Milo, dive into these 33 ancient history facts you definitely didn’t learn in school. Then, read about the seven wonders of the ancient world.

[ad_2]

Amber Morgan

Source link